Charles Darwin was born into a wealthy family in England in 1809. Never at the top of his class, Charles professed to hate schoolwork. Nonetheless, at 16, he went to the University of Edinburgh to study medicine, following his father’s footsteps. He was bored, though, and left at the end of his second year, when the prospect of watching gruesome surgeries (in the days before anesthesia) was more than he could bear.

At his father’s urging, Darwin then pursued the ministry, studying theology at the University of Cambridge. Although he never felt great inspiration in his theology studies, Darwin was in heaven at Cambridge, where he could pursue his real love, the study of nature.

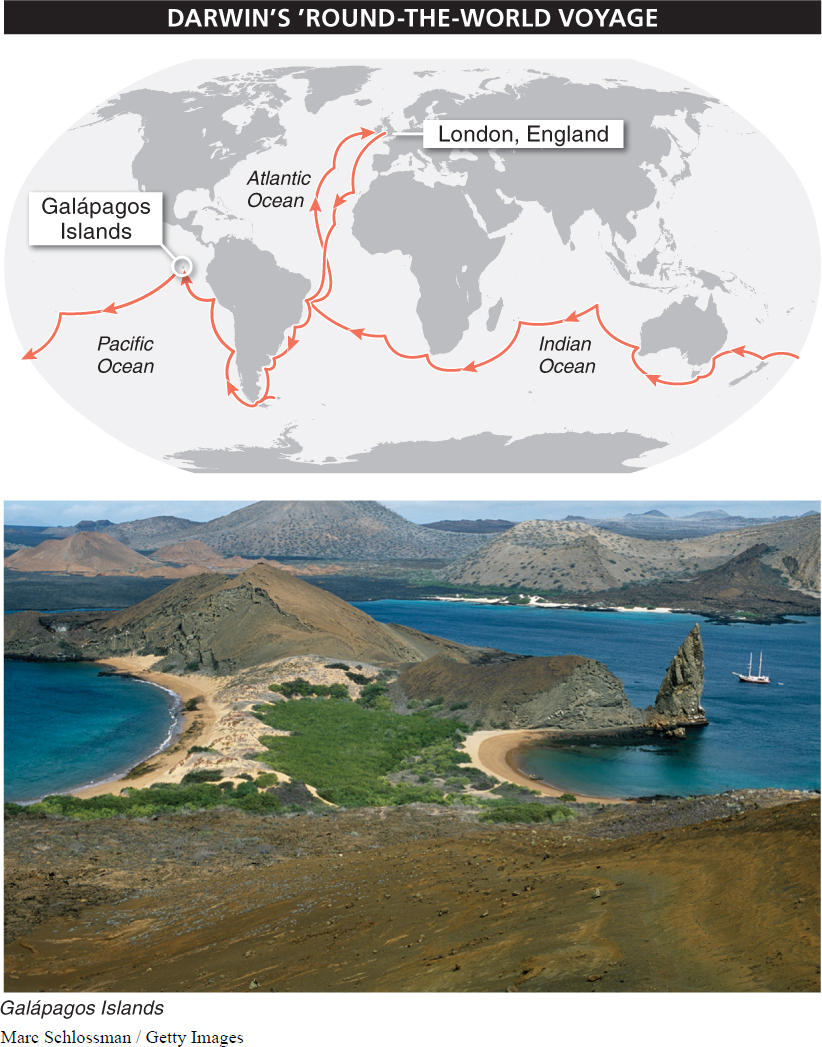

Shortly after graduation in 1831, Darwin landed his dream job, a position as a “gentleman companion” for the captain of HMS Beagle, on a five-

Once on the Beagle, Darwin found that he didn’t actually like sea travel. He was seasick for much of his time on board, writing to his cousin: “I hate every wave of the ocean with a fervor which you…can never understand.” To avoid nausea, Charles spent as much time as possible on shore. It was there that he found that fieldwork was his true calling. At each stop, he would eagerly investigate the new worlds he found. In Brazil, he was enthralled by tropical forests. In Patagonia, he explored beaches and cliffs, finding spectacular fossils from huge extinct mammals. Elsewhere, he explored coral reefs and barnacles, always packing up specimens for museums and recording his observations for later use. He was like a schoolboy on permanent summer vacation (FIGURE 8-5).

The only book Darwin took with him on the Beagle was Lyell’s Principles of Geology, which he read again and again. Intrigued by the book’s premise that the earth is constantly changing, Darwin’s mind was ripe for fresh ideas—

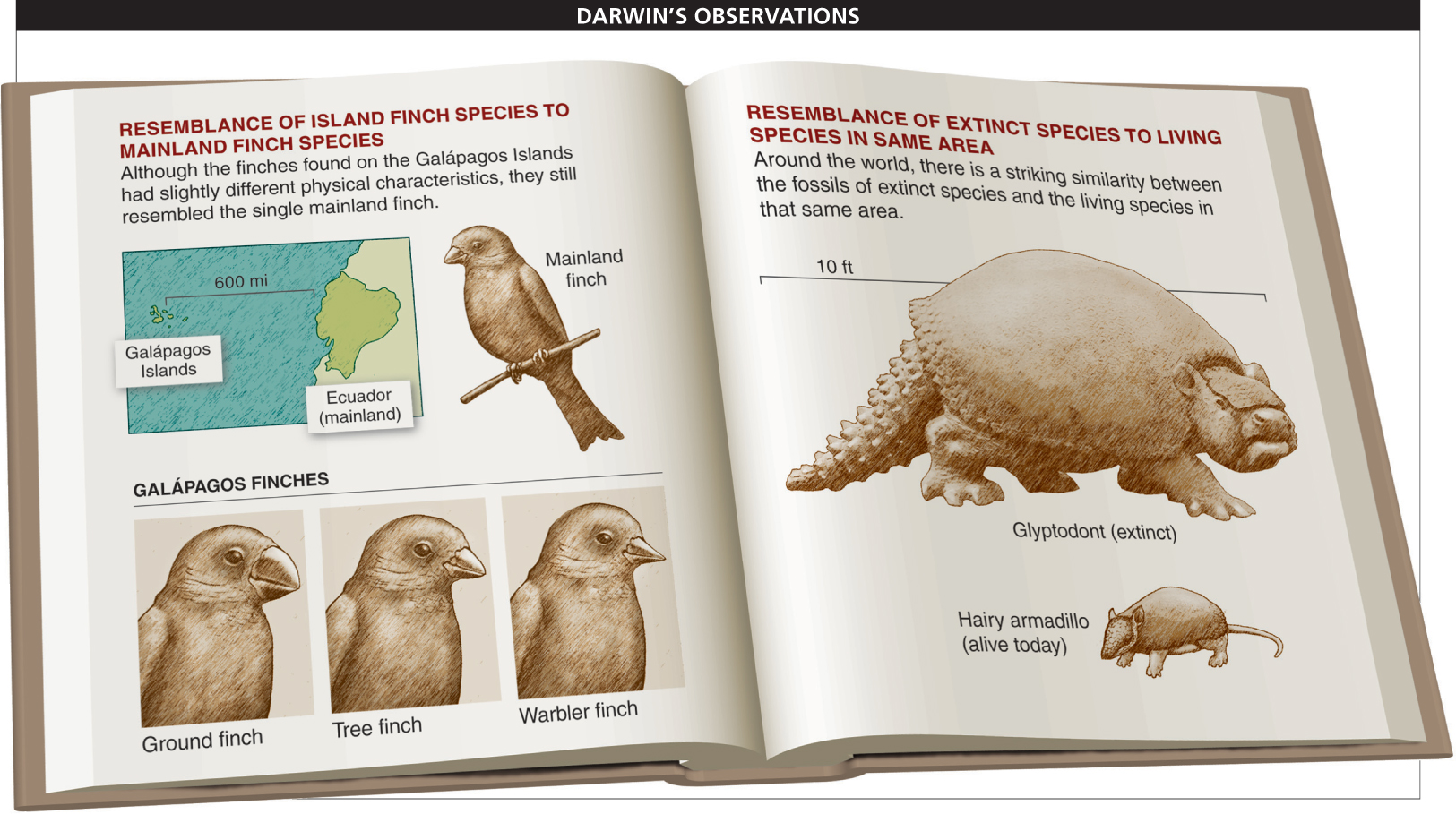

This group of volcanic islands was home to many unusual species, from giant tortoises to extremely docile lizards, which made so little effort to run away that Darwin had to avoid stepping on them. Darwin was particularly intrigued by the wide variety of birds, especially the finches, which seemed dramatically more variable than those he had seen in other locations.

Darwin noticed two important and unexpected patterns on his voyage that would be central to his discovery of a mechanism for evolution. The first involved the finches he collected and donated to the Zoological Society of London. Darwin had assumed that their differences were equivalent to differences between tall and short, curly-

322

This resemblance seemed a suspicious coincidence to Darwin. Perhaps the island finches resembled the mainland species because they used to be part of the same mainland population. Over time they may have separated and diverged from the original population and gradually formed new—

The second important but unexpected pattern Darwin noted was that, throughout his voyage, at every location there was a striking similarity between the fossils of extinct species and the living species in that same area. In Argentina, for instance, he found some giant fossils from a group of organisms called “glyptodonts.” The extinct glyptodonts looked just like armadillos, a species that still flourished in the same area. Or rather, they looked like armadillos on steroids: the average armadillo today is about the size of a house cat and weighs 10 pounds, while the glyptodonts were giants at 10 feet long and more than 4,000 pounds (see Figure 8-

If glyptodonts had lived in South America in the past, and armadillos were currently living there, why was only one of the species still alive? And why were the glyptodont fossils found only in the same places where modern armadillos lived? Darwin deduced that glyptodonts resembled armadillos because they were their ancient relatives. Again, it was a logical deduction, but it contradicted the scientific dogma of the day that species were unchanging and extinction did not occur.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 8.3

Charles Darwin was able to focus on studying the natural world when, in 1831, he got a job on a ship conducting a five-

What two important, unexpected patterns did Darwin notice on his voyage that led him to develop his theory of evolution?

The first unexpected pattern involved Galápagos finches. Initially, Darwin assumed the finches he’d collected were all of the same species but with different physical characteristics; however, it was discovered that they were all separate species. What’s more, all of the birds closely resembled the single species of mainland finch in Ecuador. He surmised that, over time, the island species had separated and diverged from the original mainland population.

The second unexpected pattern he noticed involved the striking similarity between fossils of extinct species (glyptodonts) and living species (armadillos) in the same area. He deduced that the two organisms resembled one another because the glyptodont was an ancient relative of the armadillo.

323