Kin selection and reciprocal altruism can evolve in a population of animals, as we have seen, and examples of kin selection abound in nature. As a consequence, casual observers of nature frequently see individuals acting in ways that appear altruistic, even though these individuals are truly acting—

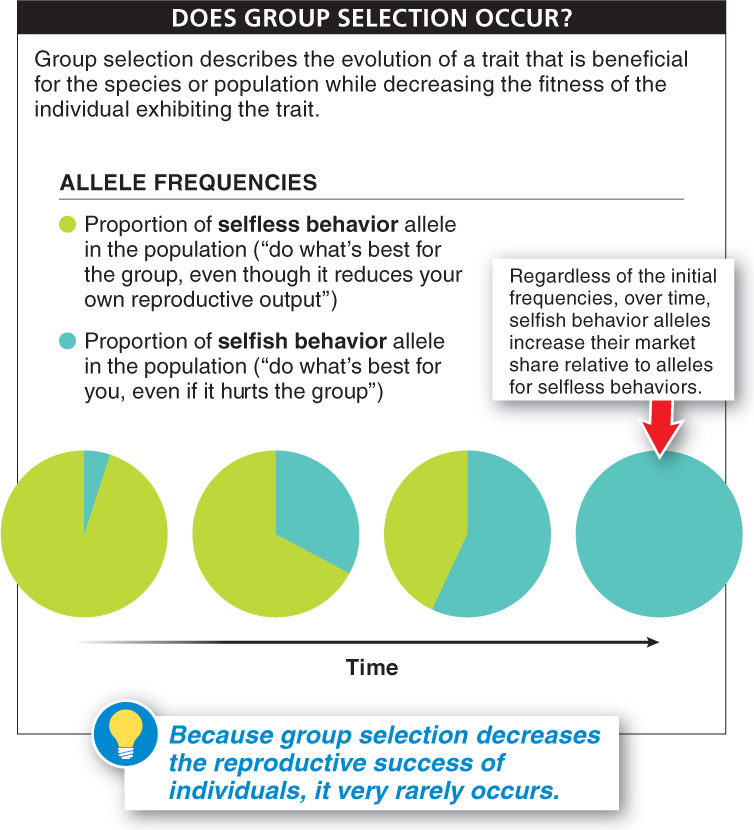

It might seem that evolution would favor individuals that behave in a manner that benefits the group, even if it comes at a cost to the individual’s own inclusive fitness. But this does not happen. Behaviors that reduce an individual’s fitness (relative to that of other individuals in the population) are not likely to evolve.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine that a new allele appears in a population (perhaps through mutation) that causes the individual carrying the allele to double its reproductive output, even though this might spell doom for the species as individuals overuse their resources. An individual carrying this “selfish” allele will pass on more copies of the allele to its offspring than an individual carrying the alternative allele, coding for the production of fewer offspring, will pass on to its offspring—

Now consider what happens when a new allele appears that causes an individual to reduce its reproductive output below what is best for that individual’s fitness. Just because a behavior (determined by an “unselfish” allele) leads to a better outcome for the group, this doesn’t mean that natural selection will favor that behavior. Even if it reduces the likelihood that, in the long run, the population goes extinct, such an allele does not increase its market share relative to the alternative “normal” or “selfish” allele. Instead, natural selection generally causes increases in the frequencies of alleles that benefit the individual carrying them, even when this comes at the expense of the group. In some special situations, it is possible for natural selection to lead to group selection. But the stringent conditions necessary for this to occur are so rarely found in nature that we almost never see it.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.9

Behaviors that are good for the species or population but detrimental to the fitness of the individual exhibiting such behaviors are not generally produced in a population under natural conditions.

Does evolution seem to favor behavior that benefits the group yet reduces the individual’s inclusive fitness?

No. Individuals generally act in ways that increase their own reproductive success. Those who value their own reproductive success above others’ success are more likely to produce many offspring and pass the “selfish” genes on to the next generation.

382