If a male simply abandons a female after mating and searches for other mating opportunities, rather than making any investment in the potential offspring, he has no risk of investing further energy in offspring that are not his. This is one way to minimize the potential costs associated with paternity uncertainty. If you don’t play, you can’t lose.

This strategy, however, is not necessarily the most effective way for a male to maximize his reproductive success. If a male has a hundred or even a thousand matings, but no offspring survive, that behavior is not evolutionarily successful. Consequently, in species for which offspring’s survival can be enhanced with greater parental investment—

In situations where males provide parental care, it is common for the male to reduce his vulnerability through some form of mate guarding. In contrast to a female, who can be certain that any offspring emerging from her body is hers, a male inhabits a “danger zone” that lasts as long as the female is fertile. If she mates with any other males during this time, the offspring she produces may not be his. If he is going to make any investments of time or energy that will benefit the offspring, he benefits by minimizing his risk in the danger zone. It is during this period that mate guarding is particularly common.

Why do so few females guard their mates as aggressively as males do?

Mate-

In a slightly subtler form of mate guarding that occurs in reptiles, insects, and many mammalian species, after copulation, males block the passage of additional sperm into the female by producing a copulatory plug. Formed in the female reproductive tract from coagulated sperm and mucus, copulatory plugs can be very effective. Male garter snakes that encounter a female snake with a copulatory plug, for example, do not attempt to court or mate with her, treating her instead as if she were not available.

389

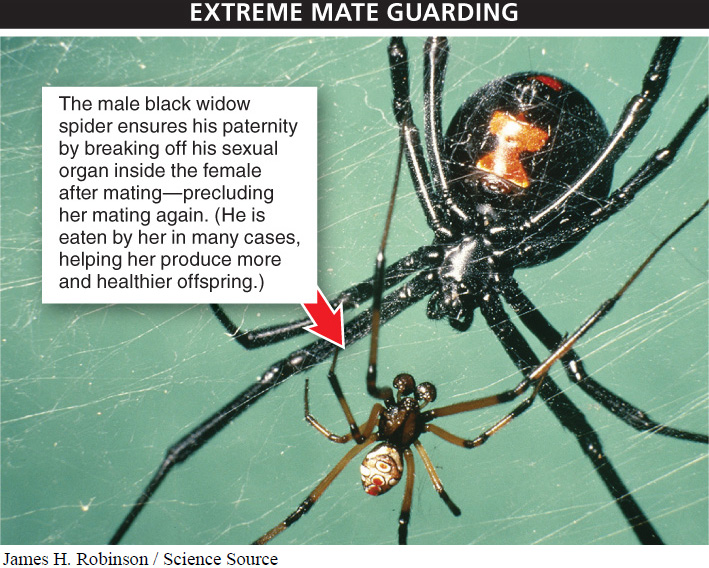

A much more extreme form of mate guarding occurs in the black widow spider: the male breaks off his sexual organ inside the female, preventing her from ever mating again. Interestingly, when the act is completed, the female usually kills and eats the male (FIGURE 9-23). In sealing his mate’s reproductive tract, the male assures himself of fathering the offspring, and in consuming her mate’s nutrient-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.13

Mate guarding can, in general, increase reproductive success by reducing additional mating opportunities for a partner, and can improve a male’s reproductive success by increasing his paternity certainty and thus reducing his vulnerability when he makes investment in offspring.

What is a copulatory plug, where does it occur, and how is it useful?

A copulatory plug is formed from coagulated sperm and mucus in the female reproductive tract of some reptiles, insects, and mammals. It serves to block the passage of additional sperm into the female, thereby guaranteeing paternity.