The challenge of communication is central to the evolution of animal behaviors, whether they relate to cooperation, conflict, or the many interactions inherent to selecting a mate. An animal must be able to convey information about its status and intentions to other individuals. And equally important, animals must be able to interpret and assess the information they get from other individuals so as to reduce the likelihood of being tricked or taken advantage of. In this section and the next, we explore the evolution of a variety of methods of animal communication and the ways in which communication can influence fitness and the evolution of other behaviors.

Not all animals need to open their mouths when they have something important to communicate. When the female silkworm moth is ready to mate, for example, she releases a potent chemical called bombykol into the air. As molecules of the chemical come in contact with the bushy antennae of a male silkworm moth—

This is just one example—

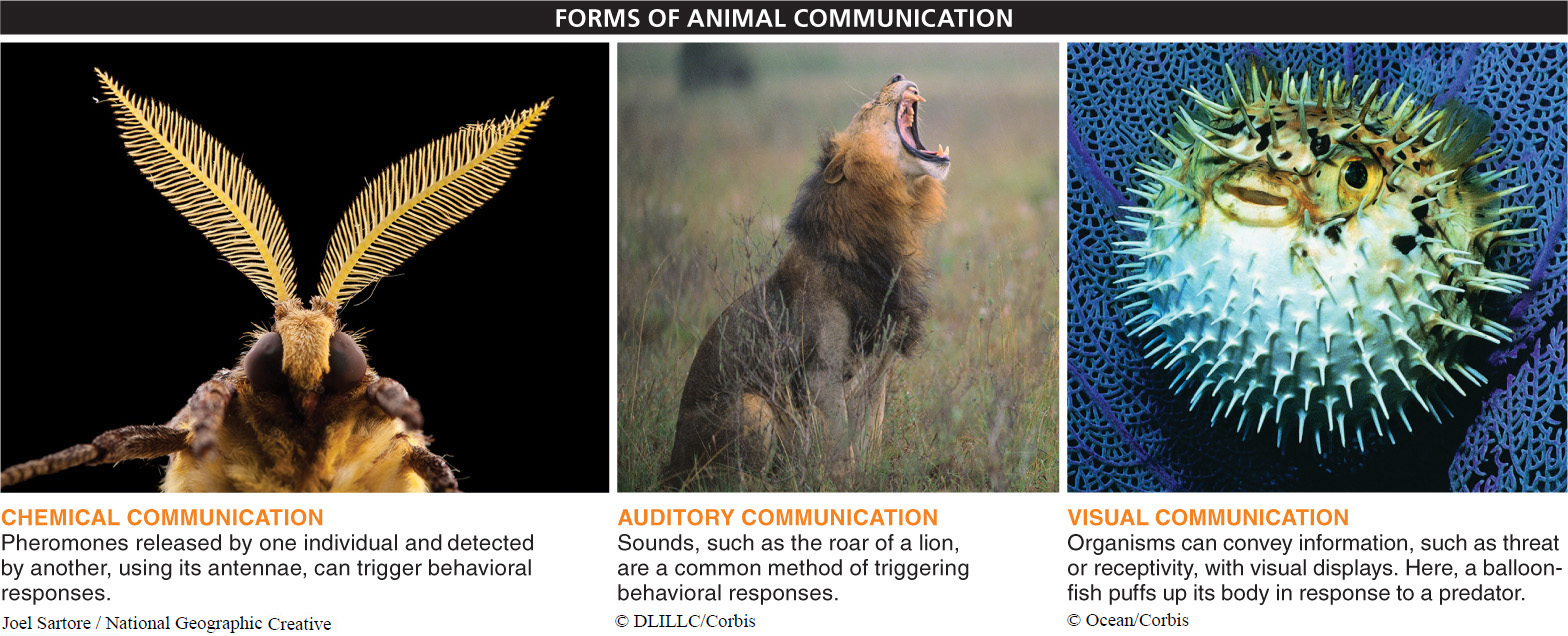

Animals communicate with many different types of signals. Three types are most common.

1. Chemical. Molecules released by an individual into the environment that trigger behavioral responses in other individuals are called pheromones. They include the airborne mate attractant of the silkworm moth, territory markers such as those found in dog urine, and trail markers used by ants. They are even used by humans: some chemicals that influence the length of the menstrual cycle in women are responsible for the synchronization of menstrual cycles that occurs in women living in group housing situations, such as in dormitories and prisons.

2. Acoustical. Sounds that trigger behavioral responses are abundant in the natural world. These include the alarm calls of Belding’s ground squirrels described earlier, the complex songs of birds, whales, frogs, and crickets vying for mates, and the territorial howling of wolves.

3. Visual. Individuals often display visual signals of threat, dominance, or health and vigor. Examples include the male baboon’s baring of his teeth and the vivid tail feathers of the male peacock.

With increasingly complex forms of communication, increasingly complex information can be conveyed. One extreme case is the honeybee waggle dance. When a honeybee scout returns to the hive after successfully locating a source of food, she performs a set of maneuvers on a honeycomb that resemble a figure 8, while wiggling her abdomen. Based on the specific angle at which the scout dances (relative to the sun’s position in the sky) and the duration of her dance, the bees that observe the dance are able to leave the hive and quickly locate the food source.

396

The complexity and power of the waggle dance raises an important question: at what point does communication become language? Language is a very specific type of communication in which arbitrary symbols represent concepts, and a system of rules, called grammar, dictates the way the symbols can be manipulated to communicate and express ideas (FIGURE 9-29).

It’s not always easy to identify language. Consider one type of communication in vervet monkeys. Vervet monkeys live in groups, and when an individual sees a predator coming, it makes an alarm call to warn the others. Unlike in most other alarm-

Does alarm calling in vervet monkeys or the honeybee waggle dance constitute language? This is debatable. Is the form of American Sign Language taught to chimpanzees and gorillas a language (see Figure 9-

397

Language influences many of the other behaviors discussed throughout this chapter. The evolution of reciprocal altruism, for example, may be influenced by language, as this makes it easier for individuals to convey their needs and resources to other individuals. Similarly, in courtship and the maintenance of reproductive relationships, language gives individuals a tool for conveying complex information relating to the resources and value they may bring to the interaction.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.17

Methods of communication—

What are the three most common types of communication signals used by animals?

Animals most commonly use chemical means (such as pheromones), acoustical means (such as alarm calls), and visual cues (such as the honeybee waggle dance).