If we look closely, we see many behaviors in the animal world that appear to be altruistic behaviors—that is, they seem to come at a cost to the individual performing them, while benefiting a recipient. When discussing altruism, we define costs and benefits in terms of their contribution to an individual’s fitness.

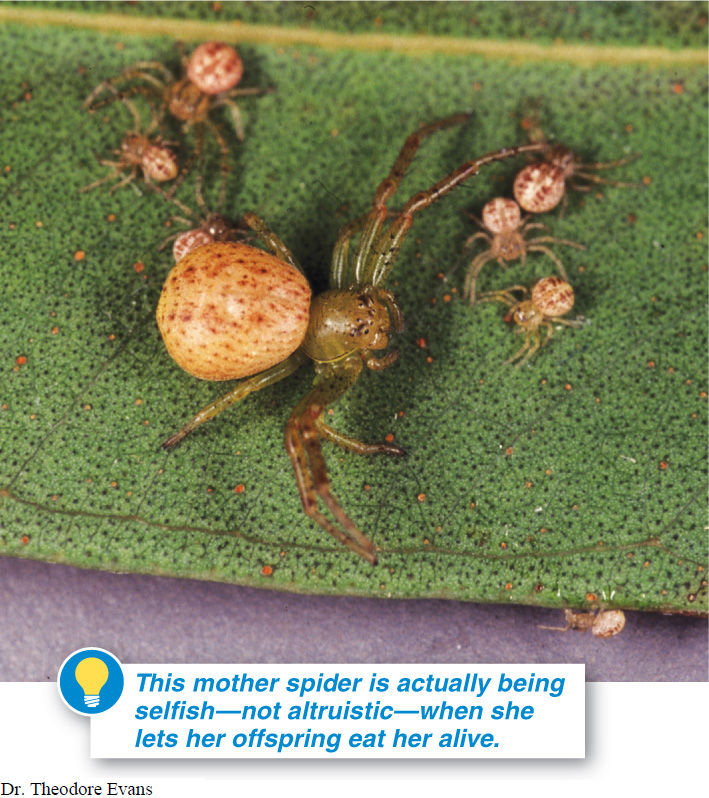

Take the case of the Australian social spider (Diaea ergandros). After giving birth to about 50 hungry spiderlings, the mother’s body slowly liquefies into a nutritious fluid that the newborn spiders consume. Over the course of about 40 days, her offspring literally eat her alive; they ultimately kill their mother, but start their lives well-

Such altruistic-

374

As it turns out, Darwin’s theory is safe. Virtually all of the apparent acts of altruism in the animal kingdom prove, on closer inspection, to be not truly altruistic; instead, they have evolved as a consequence of either kin selection or reciprocal altruism.

Kindness Toward Close Relatives: Kin Selection Kin selection is a strategy by which one individual assisting another can compensate for its own decrease in fitness if it is helping a close relative in a way that increases the relative’s fitness. Kin selection can lead to the evolution of apparently-

Kindness Toward Unrelated Individuals: Reciprocal Altruism Reciprocal altruism can lead to the evolution of apparently-

Seen in this light, both kin selection and reciprocal altruism can lead to the evolution of behaviors that are apparently altruistic but, in actuality, are beneficial—

In the next two sections, we explore kin selection and reciprocal altruism in more detail. We also investigate some of the many testable predictions about when acts of apparent kindness should occur, whom they should occur between, and how we could increase or decrease the frequency of their occurrence through a variety of modifications to the environment.

Occasionally, we see individuals engaging in behavior that is genuinely altruistic. We’ll examine how and why certain environmental situations cause individuals to behave in a way that decreases their fitness and, as such, is evolutionarily maladaptive. It is important to note here that even as genes play a central role in cooperation and conflict, people’s ability to override impulses toward selfishness is responsible for some of the rich diversity in human behavior that we see around us.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.5

Many behaviors in the animal world appear to be altruistic. In almost all cases, the apparent acts of altruism are not truly altruistic; they have evolved as a consequence of either kin selection or reciprocal altruism and, from an evolutionary perspective, are beneficial to the individual engaging in the behavior.

How is the fitness of the Australian social spider increased by allowing its offspring to eat it alive?

By making sure the new spiderlings are well nourished, the mother spider’s fitness is increased through an increase in the fitness of the offspring, even though she ultimately loses her life in the process.