It is ironic that studies of altruism among animals reveal that natural selection has primarily produced selfish behavior. And, as we saw in the previous section, when behavior appears to be altruistic, this is frequently because individuals are helping kin and, by doing so, are promoting the reproduction of copies of the genes (i.e., the alleles) that they share with close relatives. Does any apparently-

We start by examining one species with well-

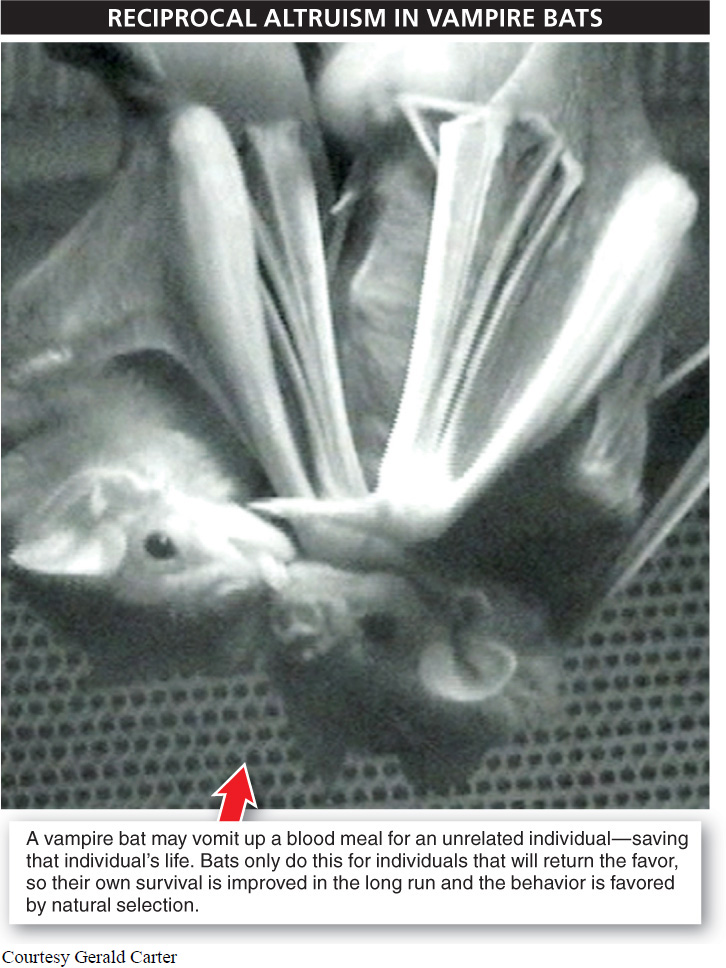

Because of their small body size (about the size of your thumb) and their very high metabolic rate, vampire bats must consume almost their entire body weight in blood each night. If they go for more than about 60 hours without finding a meal, they are likely to die from starvation. Here’s where the apparent altruism comes in: a bat that has not found food and is close to death will beg food from a bat that has recently eaten. In many cases, the bat that has just eaten will regurgitate some of the blood it has consumed into the mouth of the hungry bat, saving it from starvation. This act obviously has very high benefit for the recipient of the blood, but it comes at a cost to the sharing bat, which loses some of the caloric content of a meal it has just obtained (FIGURE 9-12).

378

Kin selection is responsible for some of the blood sharing (females often regurgitate blood for their own offspring), but, in many cases, bats give blood to unrelated individuals. How might this behavior have arisen? To answer the question, it is important to note three other features of vampire bats. First, they are able to recognize more than a hundred distinct individual bats. Second, bats that receive blood donations from non-

One method proposed to explain the evolution of this apparent altruism is that the bats giving blood to other bats in need are repaid the favor when they are in need of blood. In other words, the act only seems to be selfless, when in actuality it is selfish. With such reciprocal altruism, both individuals (at different encounters) give up something of relatively low value in exchange for getting something of great value at a later time when they need it most. In other words, they are storing goodwill in another individual, in much the same way that a person might put money in a bank for a rainy day. In both cases, individuals are protected from some of the world’s uncertainties.

Taken together, studies of bats and other mammals show that reciprocal altruism can evolve if the following three conditions are met:

- 1. Repeated interactions among individuals, with opportunities to be both the donor and the recipient of altruistic-

appearing acts - 2. Benefits to the recipient that are significantly greater than the costs to the donor

- 3. The ability to recognize and punish cheaters, individuals that are recipients of altruistic-

appearing acts but do not return the favor

In the absence of these conditions, selfishness is expected to be the norm among unrelated individuals. But in the presence of all three conditions, reciprocity masquerading as altruism is likely to occur, as it does with blood sharing among the vampire bats. The three conditions required for the evolution of reciprocal altruism are not satisfied in many animal species, which may be why altruistic-

Why are humans among the few species to have friendships?

As rare as it is in other species, reciprocal altruism is very common among humans. Friendship, among other human relationships, is built on reciprocity and is almost universal. The opportunity for friendship may be enhanced by our long life span and our ability to recognize thousands of faces and keep track of cheaters. These features are essential in individuals engaging in reciprocal altruism, because an individual becomes very vulnerable when he or she acts in an altruistic manner toward an unrelated individual. The risk is that the altruism will not be repaid, in which case the cheater enjoys greater fitness than the altruist.

Why is it easier to remember gossip than physics equations?

While cooperators, those who repay altruistic-

379

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.7

In reciprocal altruism, an individual engages in an altruistic-

How does regurgitating blood to feed an unrelated individual actually benefit a vampire bat?

Blood sharing in vampire bats is an example of reciprocal altruism. The bat regurgitating blood to feed a starving individual may someday be the recipient of a blood meal from an unrelated individual if it is starving.