Detecting Mutations with the Ames Test

People in industrial societies are surrounded by a multitude of artificially produced chemicals: more than 50,000 different chemicals are in commercial and industrial use today, and from 500 to 1000 new chemicals are introduced each year. Some of these chemicals are potential carcinogens, and some natural products are also potentially carcinogenic. One method for testing the cancer-causing potential of substances is to administer them to laboratory animals (rats or mice) and compare the incidence of cancer in the treated animals with that in control animals. Unfortunately, these tests are time-consuming and expensive. Furthermore, the ability of a substance to cause cancer in rodents is not always indicative of its effect on humans. After all, we aren’t rats!

In 1974, Bruce Ames developed a simple test for evaluating the potential of chemicals to cause cancer. The Ames test is based on the principle that both cancer and mutations result from damage to DNA, and the results of experiments have demonstrated that 90% of known carcinogens are also mutagens. Ames proposed that mutagenesis in bacteria could serve as an indicator of carcinogenesis in humans.

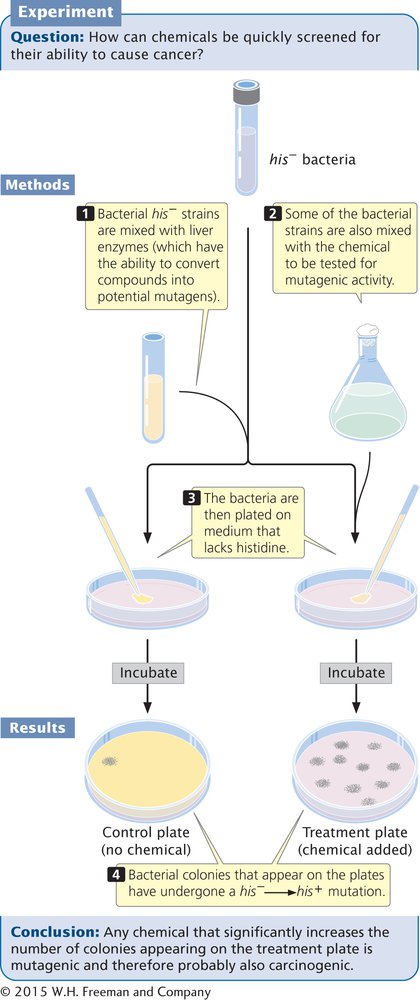

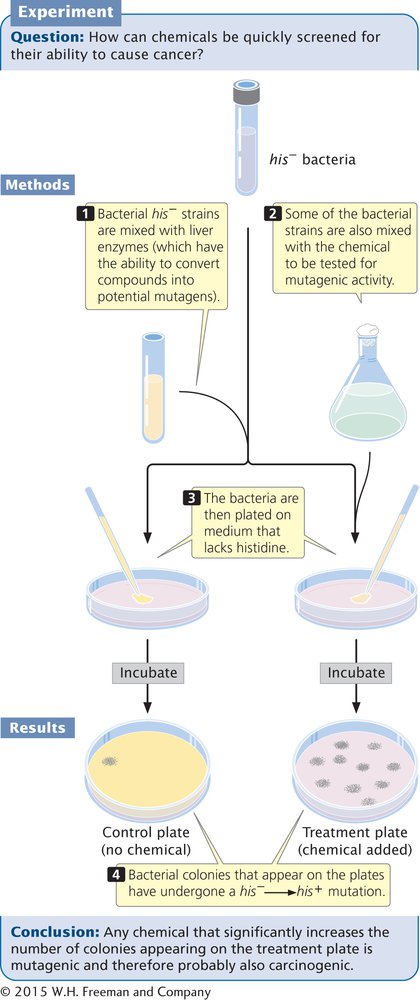

The Ames test uses auxotrophic strains of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium that have defects in the lipopolysaccharide coat, which normally protects the bacteria from chemicals in the environment. Furthermore, the DNA-repair system in these strains has been inactivated, enhancing their susceptibility to mutagens. Some compounds are not active carcinogens but can be converted into cancer-causing compounds in the body. To make the Ames test sensitive to such potential carcinogens, a compound to be tested is first incubated in mammalian liver extract that contains metabolic enzymes.

A recent version of the test (called Ames II) uses several auxotrophic strains that detect different types of base-pair substitutions. Other strains detect different types of frameshift mutations. Each strain carries a his– mutation, which renders it unable to synthesize the amino acid histidine, and the bacteria are plated on medium that lacks histidine (Figure 13.21). Only bacteria that have undergone a reverse mutation of the histidine gene (his–→his+) are able to synthesize histidine and grow on the medium, which makes these mutations easy to detect. Different dilutions of a chemical to be tested are added to plates inoculated with the bacteria, and the number of mutated bacterial colonies that appear on each plate is compared with the number that appear on control plates with no chemical (i.e., that arose through spontaneous mutation). Any chemical that significantly increases the number of colonies appearing on a treated plate is mutagenic and probably also carcinogenic.

13.21 The Ames test is used to identify chemical mutagens.

Page 361

CONCEPTS

The Ames test uses his− strains of bacteria to test chemicals for their ability to produce his− → his+ mutations. Because mutagenic activity and carcinogenic potential are closely correlated, the Ames test is widely used to screen chemicals for their cancer-causing potential.