The Early Use and Understanding of Heredity

The first evidence that people understood and applied the principles of heredity in earlier times is found in the domestication of plants and animals, which began between approximately 10,000 and 12,000 years ago in the Middle East. The first domesticated organisms included wheat, peas, lentils, barley, dogs, goats, and sheep (Figure 1.9a). By 4000 years ago, sophisticated genetic techniques were already in use in the Middle East. The Assyrians and Babylonians developed several hundred varieties of date palms that differed in fruit size, color, taste, and time of ripening (Figure 1.9b). Other crops and domesticated animals were developed by cultures in Asia, Africa, and the Americas in the same period.

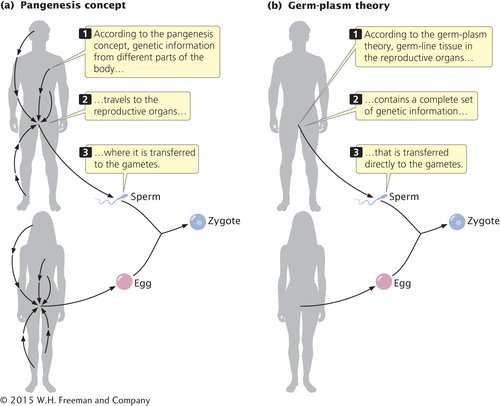

The ancient Greeks gave careful consideration to human reproduction and heredity. Greek philosophers developed the concept of pangenesis. This concept suggested that specific pieces of information travel from various parts of the body to the reproductive organs, from which they are passed to the embryo (Figure 1.10a). Pangenesis led the ancient Greeks to propose the notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, in which traits acquired in a person’s lifetime become incorporated into that person’s hereditary information and are passed on to offspring; for example, people who developed musical ability through diligent study would produce children who are innately endowed with musical ability. Although incorrect, these ideas persisted through the twentieth century.

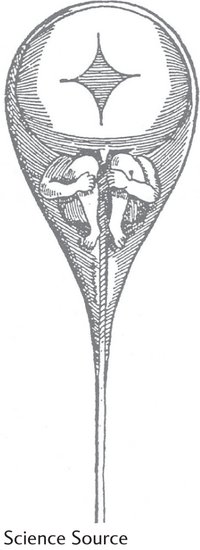

Additional developments in our understanding of heredity occurred during the seventeenth century. Dutch eyeglass makers began to put together simple microscopes in the late 1500s, enabling Robert Hooke (1635–1703) to discover cells in 1665. Microscopes provided naturalists with new and exciting vistas on life, and perhaps it was excessive enthusiasm for this new world of the very small that gave rise to the idea of preformationism. According to preformationism, inside the egg or sperm there exists a fully formed miniature adult, a homunculus, which simply enlarges during development (Figure 1.11). Preformationism meant that all traits were inherited from only one parent—

Another early notion of heredity was blending inheritance, which proposed that the traits of offspring are a blend, or mixture, of parental traits. This idea suggested that the genetic material itself blends, much as blue and yellow pigments blend to make green paint. It also suggested that after having been blended, genetic differences could not be separated in future generations, just as green paint cannot be separated into blue and yellow pigments. Some traits do appear to exhibit blending inheritance; however, thanks to Gregor Mendel’s research with pea plants, we now understand that individual genes do not blend.