2.1 Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Differ in a Number of Genetic Characteristics

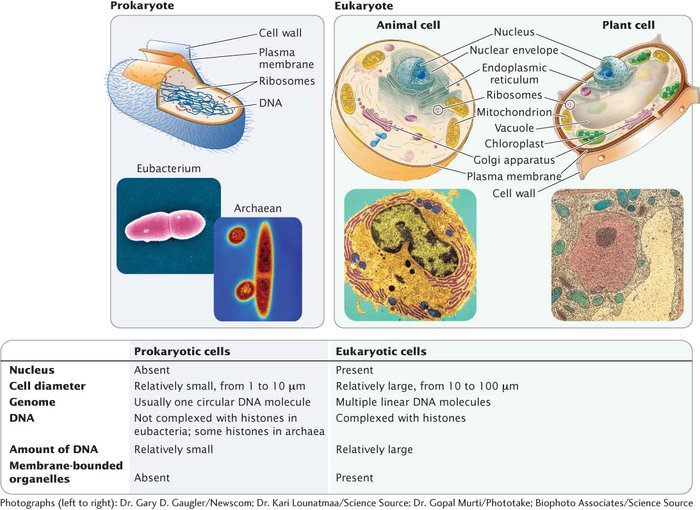

Biologists have traditionally classified all living organisms into two major groups, the prokaryotes and the eukaryotes (Figure 2.1). A prokaryote is a unicellular organism with a relatively simple cell structure. A eukaryote has a compartmentalized cell structure with components bounded by intracellular membranes; eukaryotes may be unicellular or multicellular.

Research indicates, however, that the division of life is not so simple. Although all prokaryotes are similar in cell structure, prokaryotes include at least two fundamentally distinct types of bacteria: the eubacteria (“true bacteria”) and the archaea (“ancient bacteria”). An examination of equivalent DNA sequences reveals that the eubacteria and the archaea are as distantly related to each other as they are to the eukaryotes. Although eubacteria and archaea are similar in cell structure, some genetic processes in archaea (such as transcription) are more similar to those in eukaryotes, and the archaea are actually closer evolutionarily to eukaryotes than to eubacteria. Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, there are three major groups of organisms: eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. In this book, the prokaryotic–eukaryotic distinction will be made frequently, but important eubacterial–archaeal differences will also be noted.

From the perspective of genetics, a major difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells is that a eukaryotic cell has a nuclear envelope, which surrounds the genetic material to form a nucleus and separates the DNA from the other cellular contents. In prokaryotic cells, the genetic material is in close contact with other components of the cell—

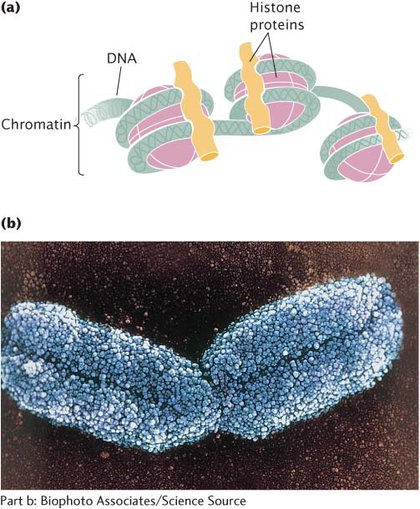

Another fundamental difference between prokaryotes and eukaryotes lies in the packaging of their DNA. In eukaryotes, DNA is closely associated with a special class of proteins, the histones, to form tightly packed chromosomes (Figure 2.3). This complex of DNA and histone proteins, called chromatin, is the stuff of eukaryotic chromosomes. The histone proteins limit the accessibility of the chromatin to enzymes and other proteins that copy and read the DNA, but they enable the DNA to fit into the nucleus. Eukaryotic DNA must separate from the histones before the genetic information in the DNA can be read. Archaea also have some histone proteins that complex with DNA, but the structure of their chromatin is different from that found in eukaryotes. Eubacteria do not possess histones, so their DNA does not exist in the highly ordered, tightly packed arrangement found in eukaryotic cells. The copying and reading of DNA are therefore simpler processes in eubacteria.

The genes of prokaryotic cells are generally on a single circular molecule of DNA—

CONCEPTS

Organisms are classified as prokaryotes or eukaryotes, and the prokaryotes consist of archaea and eubacteria. A prokaryote is a unicellular organism that lacks a nucleus, and its genome is usually a single chromosome. Eukaryotes may be either unicellular or multicellular, their cells possess a nucleus, their DNA is associated with histone proteins, and their genomes consist of multiple chromosomes.

CONCEPT CHECK 1

CONCEPT CHECK 1

List several characteristics that eubacteria and archaea have in common and that distinguish them from eukaryotes.

Eubacteria and archaea are prokaryotes. They differ from eukaryotes in possessing no nucleus, a genome that usually consists of a single circular chromosome, and a small amount of DNA.

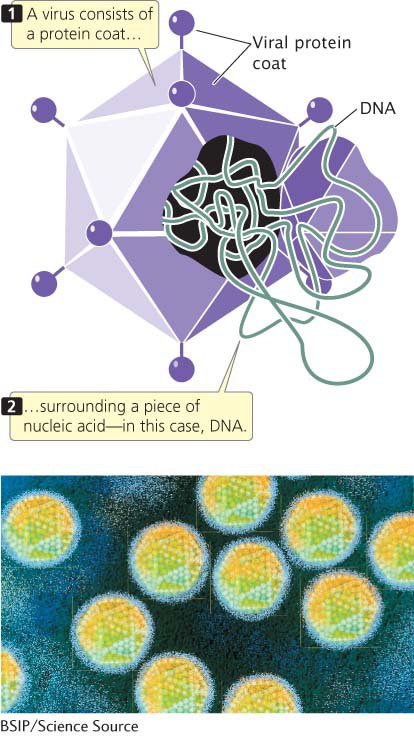

Viruses are neither prokaryotic nor eukaryotic because they do not possess a cellular structure. Viruses are actually simple structures composed of an outer protein coat surrounding nucleic acid (either DNA or RNA; Figure 2.4). Neither are viruses primitive forms of life: they can reproduce only within host cells, which means that they must have evolved after cells, not before. In addition, viruses are not an evolutionarily distinct group, but are most closely related to their hosts—