The Debate

Printed Page 256

Debates are a popular presentation format in many college courses, calling upon skills in persuasion (especially the reasoned use of evidence), in delivery, and in the ability to think quickly and critically. Much like a political debate, in an academic debate two individuals or groups consider or argue an issue from opposing viewpoints. Generally there will be a winner and a loser, lending this form of speaking a competitive edge.

Take a Side

Opposing sides in a debate are taken by speakers in one of two formats. In the individual debate format, one person takes a side against another person. In the team debate format, multiple people (usually two) take sides against another team, with each person on the team assuming a speaking role.

The affirmative side in the debate supports the topic with a resolution—a declarative statement asking for change or consideration of a controversial issue. “Resolved, that the United States government should punish flag burners” is a resolution that the affirmative side must support and defend. The affirmative side tries to convince the audience (or judges) to address, support, or agree with the topic under consideration. The negative side in the debate attempts to defeat the resolution by dissuading the audience from accepting the affirmative side’s arguments.

Advance Strong Arguments

Whether you take the affirmative or negative side, your primary responsibility is to advance strong arguments in support of your position. Arguments usually consist of the following three parts (see also Chapter 24):

- Claim: A claim makes an assertion or a declaration about an issue: “Females are discriminated against in the workplace.” Depending on your debate topic, your claim may be one of fact, value, or policy.

- Evidence: Evidence is the support offered for the claim: “According to a recent report by the U.S. Department of Labor, women make 28 percent less than men in comparable jobs and are promoted 34 percent less frequently.”

- Reasoning: Reasoning (e.g., warrants; see p. 195) is a logical link or explanation of why the evidence supports the claim: “Females make less money and get promoted less frequently than males.”

Flowing the Debate

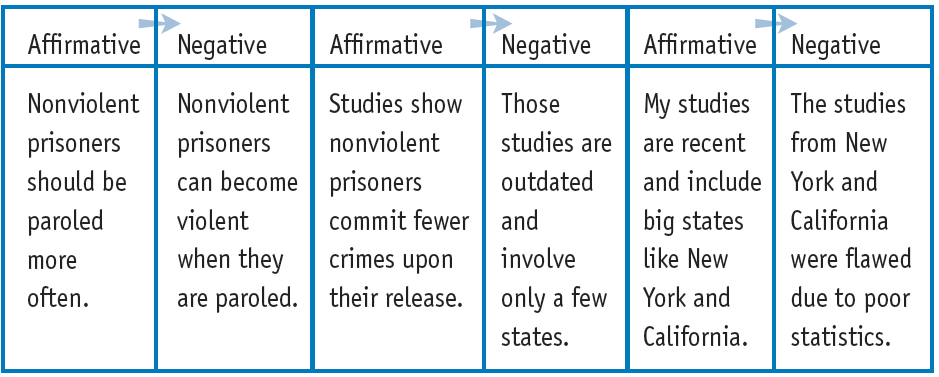

In formal debates (in which judges take notes and keep track of arguments), debaters must attack and defend each argument. “Dropping” or ignoring an argument can seriously compromise the credibility of the debater and her or his side. To ensure that you respond to each of your opponent’s arguments, try using a simple technique adopted by formal debaters called “flowing the debate” (see Figure 30.1). Write down each of your opponent’s arguments, and then draw a line or arrow to indicate that you (or another team member) have refuted it.

Debates are characterized by refutation, in which each side attacks the arguments of the other. Refutation can be made against an opponent’s claim, evidence, reasoning, or some combination of these elements. In the previous argument, an opponent might refute the evidence by arguing, “The report used by my opponent is three years old, and a new study indicates that we are making substantial progress in equalizing the pay among males and females; thus we are reducing discrimination in the workplace.”

Refutation also involves rebuilding arguments that have been refuted or attacked by the opponent. This is done by adding new evidence or attacking the opponent’s reasoning or evidence.

Checklist: Tips for Winning a Debate

![]() Present the most credible and convincing evidence you can find.

Present the most credible and convincing evidence you can find.

![]() Before you begin, describe your position and tell the audience what they must decide.

Before you begin, describe your position and tell the audience what they must decide.

![]() If you feel that your side is not popular among the audience, ask them to suspend their own personal opinion and judge the debate on the merits of the argument.

If you feel that your side is not popular among the audience, ask them to suspend their own personal opinion and judge the debate on the merits of the argument.

![]() Don’t be timid. Ask the audience to specifically decide in your favor, and be explicit about your desire for their approval.

Don’t be timid. Ask the audience to specifically decide in your favor, and be explicit about your desire for their approval.

![]() Point out the strong points from your arguments. Remind the audience that the opponent’s arguments were weak or irrelevant.

Point out the strong points from your arguments. Remind the audience that the opponent’s arguments were weak or irrelevant.

![]() Be prepared to think on your feet (see Chapter 17 on impromptu speaking).

Be prepared to think on your feet (see Chapter 17 on impromptu speaking).

![]() Don’t hide your passion for your position. Debate audiences appreciate enthusiasm and zeal.

Don’t hide your passion for your position. Debate audiences appreciate enthusiasm and zeal.