Chapter Introduction

Jasper White/Getty Images

Supplements, Herbs, and Functional Foods SURPRISING STUDIES ON THE VALUE OF VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTS

Page 259

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Identify at least three situations or conditions for which specific supplementation may be warranted (Infographic 12.2)

Provide an overview of the regulatory policies in the United States for dietary supplements compared with those for prescription or conventional drugs (Infographic 12.3)

Describe the types of information provided on a Supplement Facts Panel (Infographic 12.4)

Describe how approved health claims differ from structure/function claims for dietary supplements and provide at least two examples of each (Infographics 12.5 and 12.6)

Provide an example of an herbal supplement, and explain its possible benefits and adverse effects (Infographic 12.9)

Describe what might make a food “functional” and how these foods might affect health, dietary quality, and overall nutrient intake (Infographic 12.10)

Characterize the difference between probiotics and prebiotics, and give examples of each (Infographic 12.11)

Gilbert Omenn swallowed hard. It was April 1993, and he had just been called into an emergency breakfast meeting with two scientists from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), a division of the United States National Institutes of Health. “We have a very serious problem. We would like to tell you all about it,” the NCI scientists told Omenn, who at the time was Dean of the University of Washington’s School of Public Health and Community Medicine. “On one critical condition: You must not tell anybody else.”

Omenn didn’t like secrets, but he agreed—not least because he wanted to know if their concerns had anything to do with the large NCI-funded clinical trial he was leading called Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET). He was testing whether large doses of beta-carotene plus vitamin A could prevent lung cancer in more than 18,000 people who either currently smoked, had smoked in the past, or had been exposed to asbestos. As it turned out, the NCI scientists were worried about a different ongoing antioxidant trial being conducted by researchers at the NCI and in Finland. The scientists pulled out some of the preliminary Finnish trial data and laid it out in front of him.

Page 260

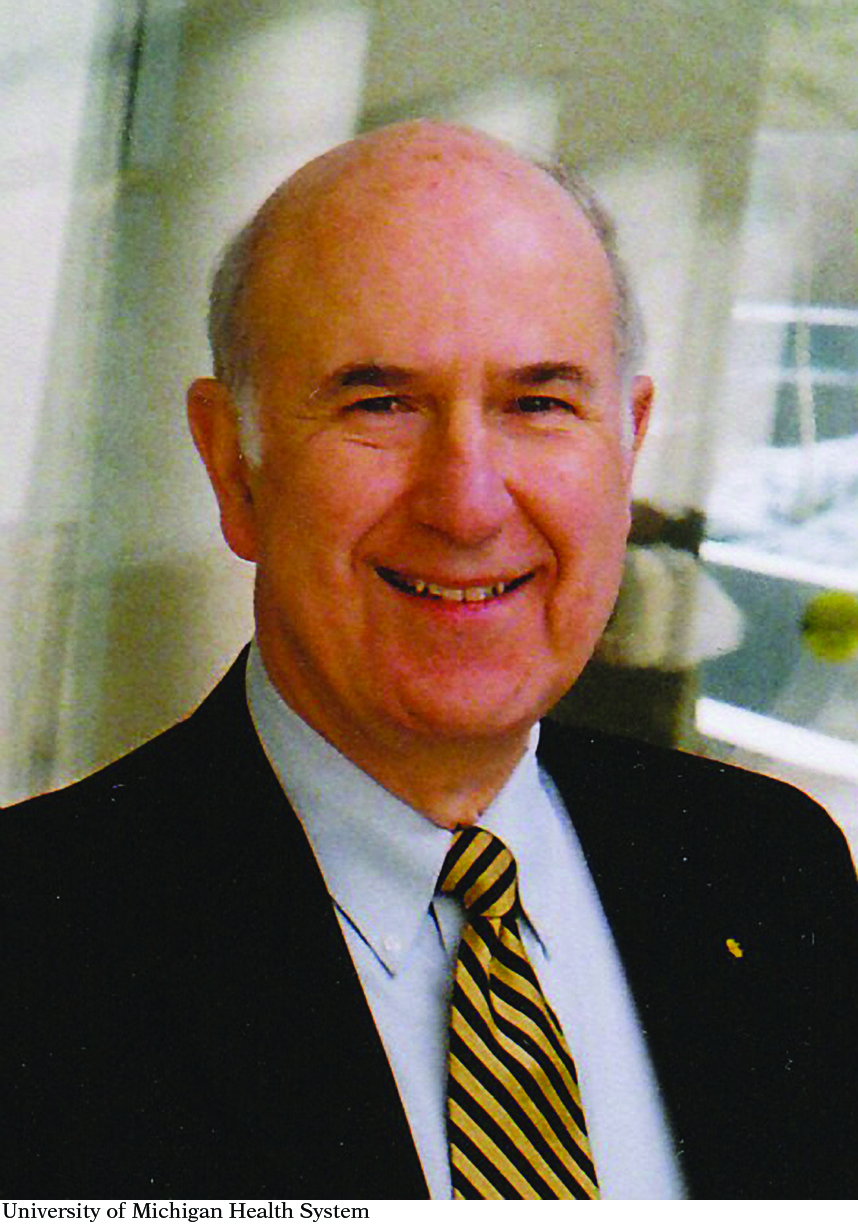

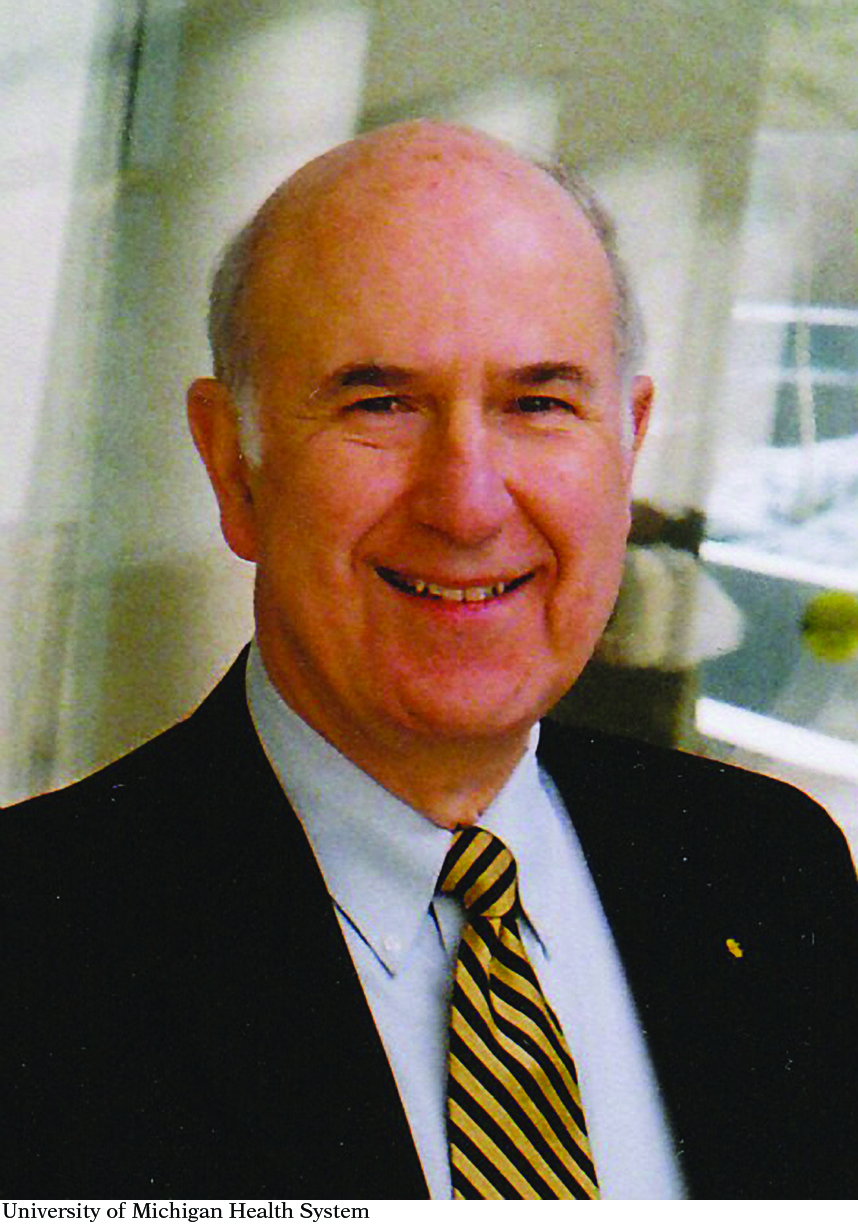

Gilbert Omenn, Professor of Internal Medicine, Human Genetics, and Public Health at the University of Michigan. Omenn was principal investigator of the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET) which explored potential lung cancer and heart disease preventatives.

University of Michigan Health System

Omenn was looking at the lung cancer rates of people in the Finnish trial who had taken beta-carotene plus either vitamin E supplements or sugar pills. “What it showed was a difference in cancer incidence in the two treatment groups of the study that received beta-carotene, starting a year or two after the beginning, getting bigger and bigger,” Omenn recalls. That made sense: Beta-carotene was probably preventing cancer, but the placebo wasn’t. But when Omenn saw the data labels, he froze. The study participants who were developing cancer were the ones taking the beta-carotene—not the ones taking placebos.

“This was a big shock,” Omenn recalled—so much so that he didn’t believe it. The labels must have accidentally been switched, he said. The NCI scientists assured him they weren’t.

In closed meetings that Omenn attended over the course of the next few weeks, the cancer agency confirmed that beta-carotene had increased lung cancer risk by 18% compared with placebo in the Finnish trial, although vitamin E seemed to have no effect. All the while, Omenn’s own trial continued. A year later, in late spring 1994, the NCI gave Omenn the green light to tell his colleagues and his 18,314 trial participants about the Finnish findings. Only 606 of his participants chose to drop out of the study. By January 1996, Omenn had enough data to crunch numbers, and what he discovered was distressing: The combination of beta-carotene and vitamin A was increasing his participants’ risk of lung cancer by a whopping 28% compared with sugar pills. For the safety of everyone enrolled, Omenn immediately stopped the trial, 21 months ahead of schedule. Looked at another way, Omenn’s results, which were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute later that year, suggested that the people had a 1 in 1,000 increased chance of developing cancer each year as a direct result of taking the beta-carotene/vitamin A supplements.

Page 261

Does vitamin A supplementation prevent cancer? Observational studies had shown that people eating more fruits and vegetables, which are rich in beta carotene (that the body can convert into retinol, or vitamin A), had lower rates of lung cancer. The Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET) tested the combination of beta-carotene and vitamin A supplements in men and women at high risk of developing lung cancer. The CARET intervention was stopped 21 months early because of clear evidence of no benefit and substantial evidence of possible harm.

StockImages/Alamy

Chances are, if you opened the medicine cabinet in your bathroom or the cabinets in your kitchen you would find a vitamin bottle, or a drink powder, or perhaps a nutrition bar of some sort. Dietary supplements are a more than 30 billion dollar a year industry, more than 65,000 varieties are sold in the United States today, and more than half of all Americans take supplements in an attempt to stay healthy. The most common supplements are multivitamin and multimineral supplements, followed by calcium, omega-3 fatty acid supplements (fish oil), and vitamin D. Yet fewer than a quarter of Americans who take supplements do so at the recommendation of a qualified health care provider.

Dietary supplements are a big business in the U.S. According to NHANES data, the percentage of the U.S. population who used at least one dietary supplement increased from 42% in 1988–1994 to 53% in 2003–2006.

Keith Brofsky/Getty Images

Page 262

Supplements are beneficial for some individuals, particularly those who cannot meet their nutritional requirements because of disease, increased need, or restricted diets. But many people take supplements despite the fact that they are already in good health and likely get adequate nutrients through their diet. Women are more likely to take supplements to keep their bones healthy, while men tend to pop pills in the hope of preventing heart problems. But do these supplements actually help? A growing body of research, including the results of those National Cancer Institute trials from the 1990s, suggests that high doses of single vitamins, as well as lower doses of multivitamins, may be only mildly helpful at best and may pose health risks at worst. The majority of studies have found that multivitamin/mineral supplement use does not decrease the risk of death or chronic disease, and several studies have even reported an increased risk of death associated with their use. People who take supplements tend to eat well already, so those who might benefit the most from supplements are, ironically, often the ones who are least likely to take them.