REGULATION OF DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS

The FDA regulates both dietary supplement products and the ingredients found within them, and it does so under a different set of regulations than those governing “conventional” foods and drugs. Unlike drug regulation, the FDA does not approve dietary supplements for their effectiveness or safety before they are made available to consumers. Dietary supplements do not undergo the rigorous testing for effectiveness, interaction, or safety requirements that prescription and over-

GENERALLY RECOGNIZED AS SAFE (GRAS) any substance intentionally added to food that is generally recognized, among qualified experts, as having been adequately shown to be safe under the conditions of its intended use; not subject to premarket review and approval by the FDA

Although dietary ingredients found in supplements are federally regulated, ingredients and additives that were already in the food supply prior to when DSHEA went into effect on October 15, 1994, were grandfathered in as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS). GRAS substances don’t need FDA approval before being marketed, so many long-

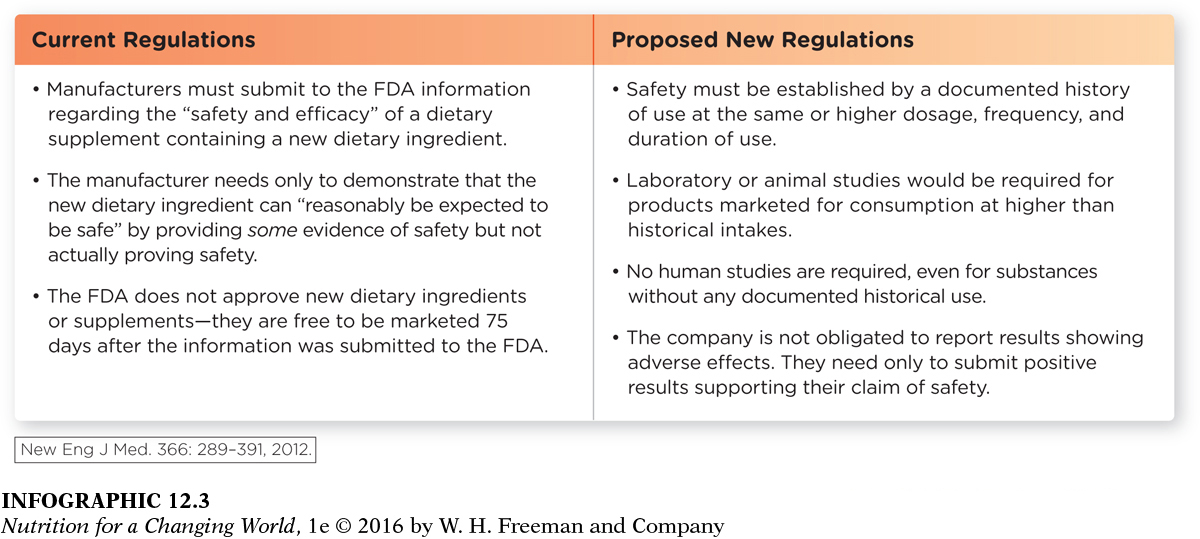

For new dietary ingredients, DSHEA requires that manufacturers must notify the FDA 75 days before the product is to be introduced and provide the agency with evidence that the supplement is “reasonably expected to be safe”. Unfortunately, it is common for supplement distributors and manufacturers to ignore this requirement, as well as other regulations.

Because the FDA does not regulate dietary supplements as rigorously as it does drugs, supplements are sometimes sold contaminated with banned substances or prescription drugs. In 2010, for instance, the agency warned consumers not to take the Chinese weight-

The FDA is responsible for taking action against unsafe or improperly labeled dietary supplements after they go to market, but this is not easy to do: The agency has to prove that the product is unsafe to restrict its use or remove it, and “there’s no effective system that the FDA has to identify these supplements, so hazardous supplements stay on the marketplace for years,” Cohen says. Even when the FDA announces that a supplement is unsafe, it may not cease being sold. In a 2011 study, Cohen and his colleagues found that after the FDA recalled a popular weight-

Question 12.2

Give an example of “some evidence of safety” that would NOT actually prove that the ingredient is safe.

Give an example of “some evidence of safety” that would NOT actually prove that the ingredient is safe.

To prove “some evidence of safety” a manufacturer could show that a dietary ingredient has been used for one purpose (for example, in small quantities used as a sweetener) without a reported problem and could be reasonably expected to be safe to consume in another context (for example, in larger quantities as a sleep aid).