UNDERSTANDING SUPPLEMENT LABELS

The FDA requires that dietary supplement manufacturers list certain details about their products on product labels. The general information required on the package includes the name of the product; the word “supplement” or a statement that the product is a supplement; the quantity of the package contents; the name and location of the manufacturer, packer, or distributor; and directions for using the product.

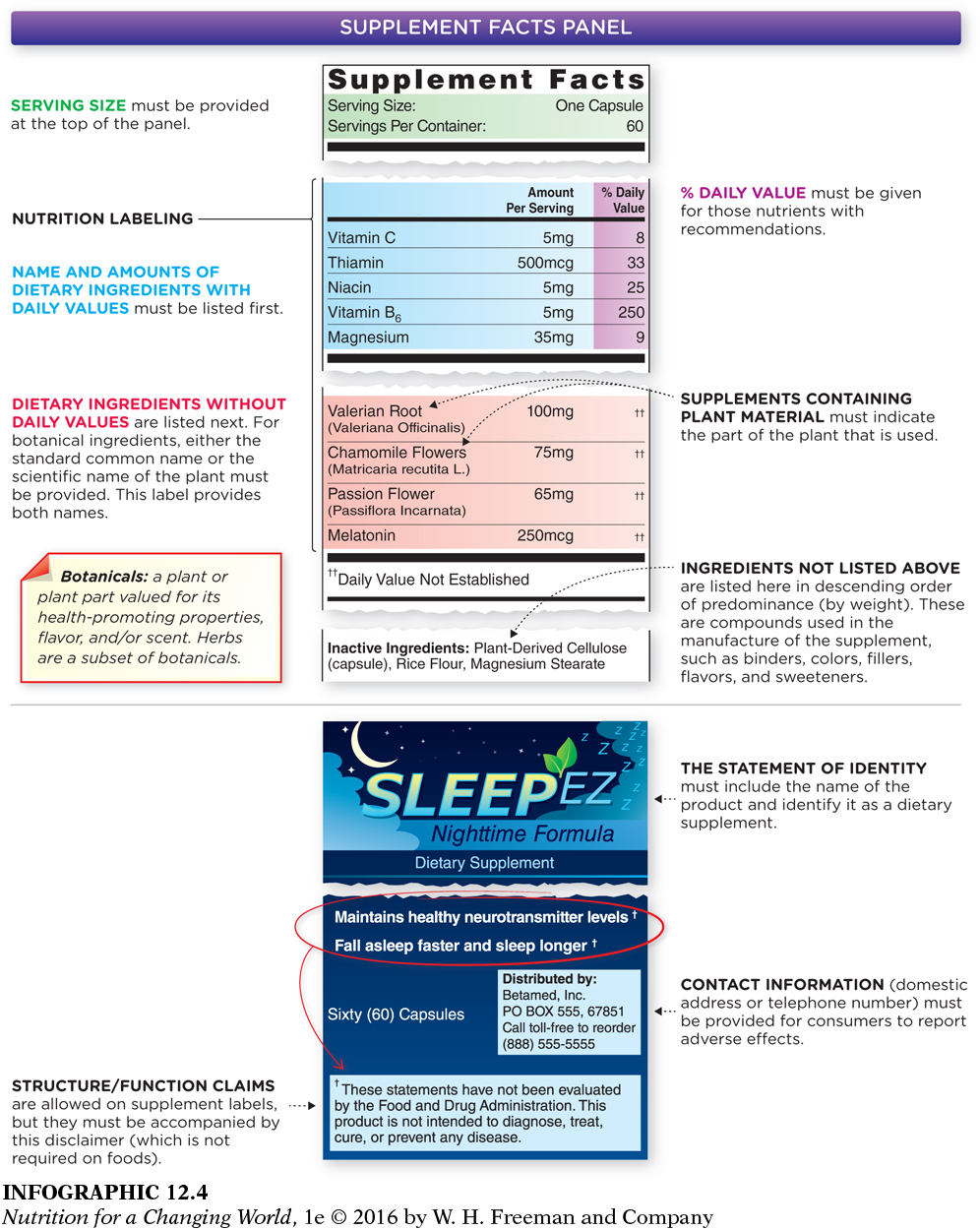

SUPPLEMENT FACTS PANEL package label that must indicate that the product is a supplement, not a conventional food, and must include serving size and amount of product per serving size, the percent of Daily Value that a particular ingredient or nutrient provides per serving, and a list of the product’s dietary ingredients

In addition to the general information, a supplement must also have what is called a Supplement Facts Panel. This panel must include information on serving size and amount of product per serving size (by weight), the percent of Daily Value (%DV) that a particular ingredient or nutrient provides per serving (if this is known), and a list of the product’s dietary ingredients (INFOGRAPHIC 12.4). If a dietary ingredient is a botanical, the panel must list the scientific name of the plant or the common name that has been standardized in the reference book Herbs of Commerce (2000 edition). The panel must also include name of the plant part that has been used. If the dietary ingredient is a proprietary blend, meaning a blend that is exclusive to the manufacturer, the Supplement Facts Panel must list the total weight of the blend and its components in descending order of predominance by weight.

Question 12.3

Must all ingredients be declared on the label of a dietary supplement?

Must all ingredients be declared on the label of a dietary supplement?

Dietary ingredients and inactive ingredients are listed on the label of a supplement.

Supplements must also include another ingredients panel. This lists all nondietary components found in the product such as fillers; water; artificial colors; sweeteners; flavors; and processing aids, such as binders, gelatin, and stabilizers. These ingredients are listed by common name or proprietary blend in descending order of predominance by weight. The ingredients listed in this panel may include the sources of the dietary ingredients if they are not identified in the Supplement Facts Panel—

Finally, supplement labels may also contain cautionary statements about potential side effects, but if a supplement does not have a cautionary statement, it does not mean that the product is completely safe. Unlike conventional drugs, supplement manufacturers do not have to list known adverse effects on their labels.

Health claims

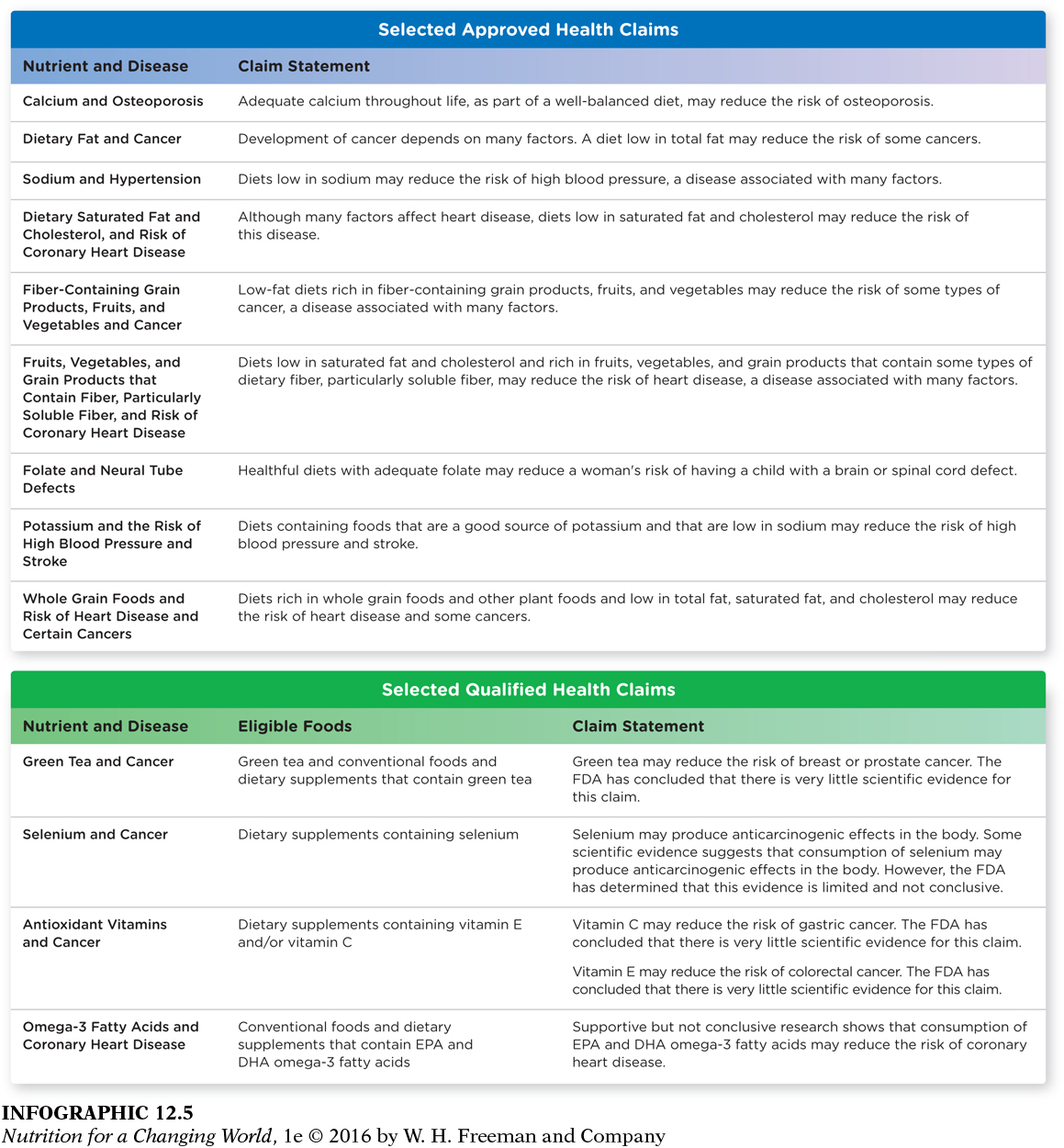

Supplement labels can also include health claims that describe a relationship between a dietary supplement ingredient and a reduced risk of a disease or condition. The FDA must pre-

Question 12.4

Which one of the sample qualified health claims has the strongest supporting evidence?

Which one of the sample qualified health claims has the strongest supporting evidence?

The claim linking omega-

Structure/function claims

Supplement manufacturers can’t make claims that their product treats, prevents, or cures disease unless it has been approved for a health claim or qualified health claim. However, companies can make a structure/function claim on the label about how that product could affect the body’s structure or function. (INFOGRAPHIC 12.6) “Calcium builds strong bones” is an example of a structure-

Question 12.5

What is the difference between the statements “calcium builds strong bones” and “calcium reduces the risk of osteoporosis”?

What is the difference between the statements “calcium builds strong bones” and “calcium reduces the risk of osteoporosis”?

“Calcium builds strong bones” makes a claim that calcium affects the body’s structure (bones). It is an acceptable structure/function claim. “Calcium reduces the risk of osteoporosis” is not an acceptable structure/function claim because it promises to prevent the disease of osteoporosis.

Supplement quality

How do we know if supplements on the market are pure and of high quality? The FDA does not monitor supplements for quality assurance, potency, purity, or efficacy—

Consumers do have some ways of gauging supplement quality, though. Independent labs test supplements that manufacturers voluntarily submit; some labs also do product reviews. Organizations such as United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP)—a scientific nonprofit organization that sets standards for the identity, strength, quality, and purity of medicines, food ingredients, and dietary supplements distributed and consumed worldwide—