CALCIUM, MAGNESIUM, AND PHOSPHORUS HAVE DIVERSE STRUCTURAL ROLES IN THE BODY

Bones are the structural component of the body that shield our brain and organs from injury and make it possible to move. Minerals make up approximately two-

Functions and sources of calcium

Calcium (Ca) is the most abundant mineral in the body, with 99% found in bones and teeth, where it provides an essential structural component for their formation. Bones provides a reservoir of calcium that can be tapped to supply calcium to body fluids when its concentration in blood decreases. The other 1% is located in the body cells and fluids, where it is necessary for many essential functions such as blood clotting, hormone secretion, muscle contraction, and nerve transmission.

CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS the balance between the actions of parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, and the kidneys to tightly control serum calcium levels

PARATHYROID HORMONE (PTH) a hormone released from the parathyroid gland in response to low serum calcium levels

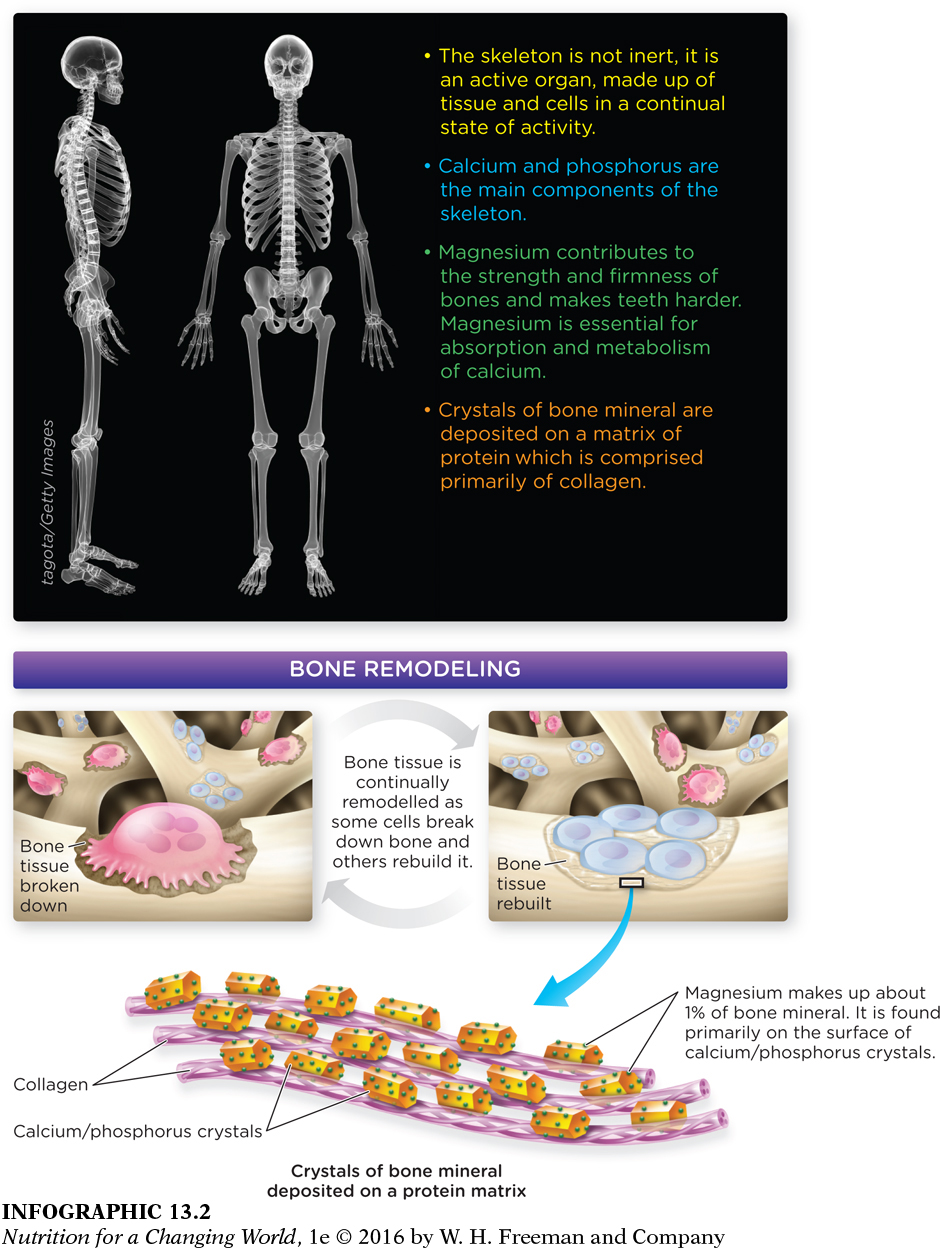

BONE REMODELING the process of continuous bone breakdown and rebuilding, which is required for bone maintenance and repair

Because so many critical body functions depend on calcium, its concentration in blood is tightly regulated so that it remains nearly constant regardless of dietary calcium intake. When calcium in blood falls even slightly, it will be released from bone to maintain steady blood calcium levels. The mechanism by which the body maintains calcium levels in the blood is known as calcium homeostasis. When blood calcium levels fall, the parathyroid gland releases parathyroid hormone (PTH), which stimulates the production of the active form of vitamin D (calcitriol) and thereby increases calcium absorption from the intestine. (Refer back to Infographic 10.4 to review this process.) PTH and activated vitamin D work together to mobilize calcium from the bone and decrease calcium excretion from the kidneys.

Calcium plays an indispensable role in bone and tooth formation. In fact, bone is constantly being broken down and rebuilt in a process known as remodeling. Bone remodeling is necessary not only to maintain blood calcium levels, but it is also required during bone growth in the young, to allow bone to adapt to strain, and to repair the microscopic damage that occurs daily.

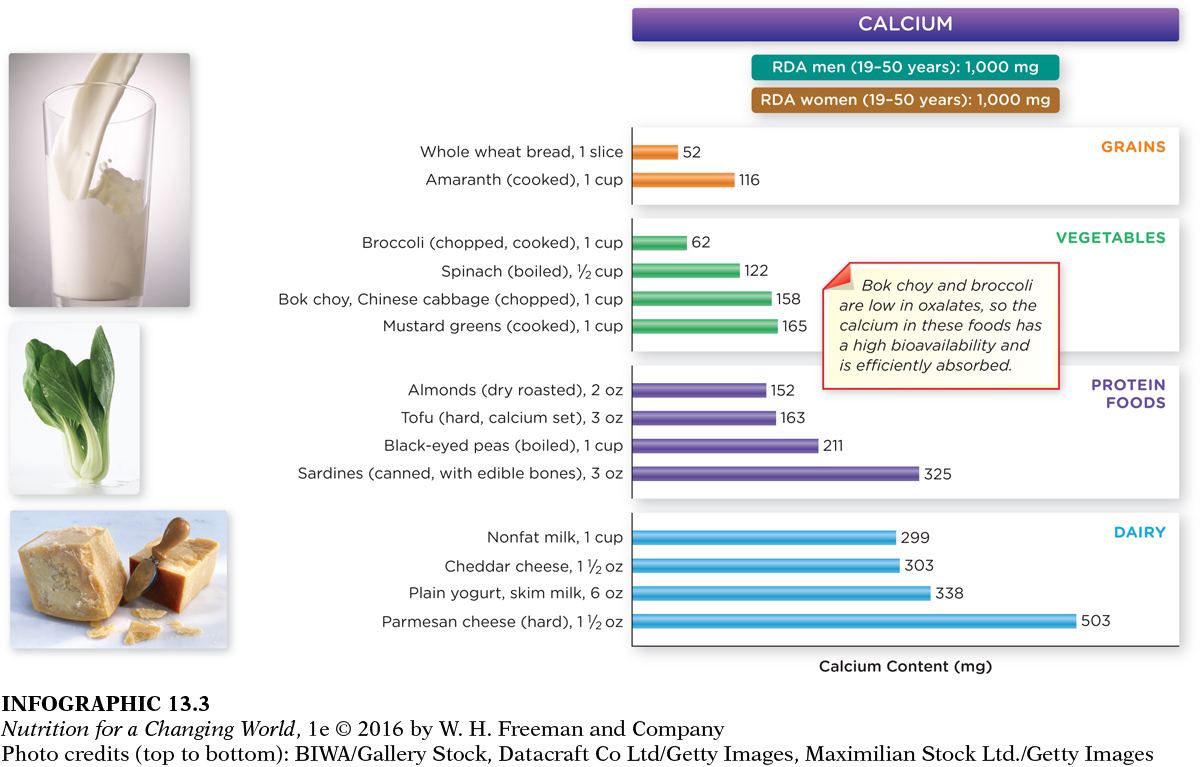

The Institute of Medicine has set the AI for calcium at 1,000 milligrams per day for men and women aged 19 to 50 years; the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) is set at 2,500 milligrams. Calcium-

Question 13.1

Identify several foods that together would allow you to meet your RDA for calcium without consuming more than a single serving of any one food.

Identify several foods that together would allow you to meet your RDA for calcium without consuming more than a single serving of any one food.

There are many ways to meet the 1,000 mg RDA for calcium; for example, you could consume 1 slice of whole wheat bread, ½ cup of boiled spinach, 3 ounces of sardines, and 1½ ounces of Parmesan cheese.

Calcium and bone health

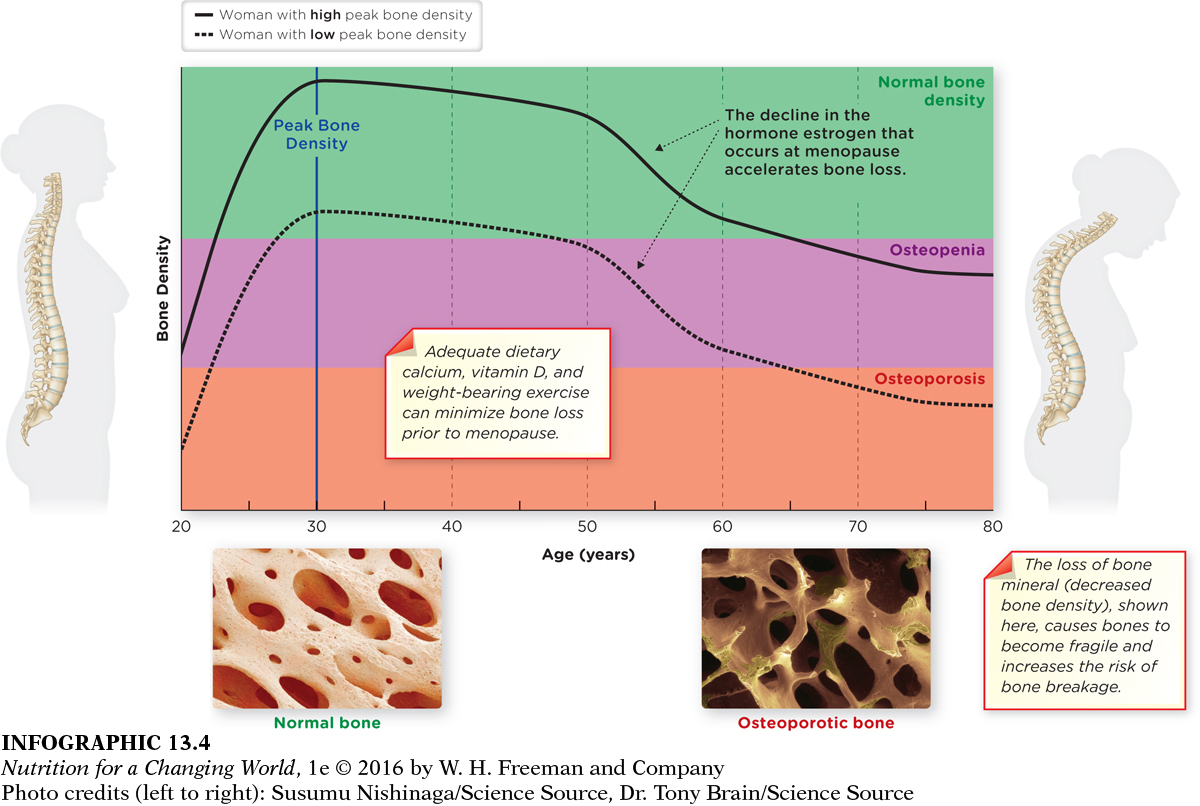

With age, the balance of calcium release and deposition in bone changes. During years of growth, such as childhood, more calcium is added to bone in relation to the amount lost, but as we get older, bone breakdown often exceeds formation. Peak bone mass is established at around age 30, so it is important, during the formative years of bone development, to consume adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D. If intake is low or absorption is impaired, bone loss occurs because the body uses the calcium in bone to maintain blood levels and support calcium-

OSTEOPENIA a condition characterized by low bone mineral density

OSTEOPOROSIS a bone disease in which the bone density and total mass are decreased, leading to porous bones, increased fragility, and susceptibility to fractures

Most people realize that adequate calcium status is important for optimal bone health. However, a significant number of Americans have low bone mass. Although some bone loss is a normal consequence of aging, bone loss accelerates in postmenopausal women because of low levels of the hormone estrogen. This reduced bone mass, or bone density, along with reduced mineral content, can lead to a condition called osteopenia. When osteopenia becomes severe, and bone loss worsens to cause bones to be fragile and porous, a person develops osteoporosis, or “porous bones,” and the risk of bone fractures is dramatically increased.

Osteoporosis afflicts more than 10 million Americans; approximately one-

Calcium supplementation

HYPERCALCEMIA a high level of calcium in the blood

Although it is tempting to think that supplements are a “sure thing” to confirm that you are getting enough calcium, supplementation can potentially push intake to higher-

Functions of magnesium

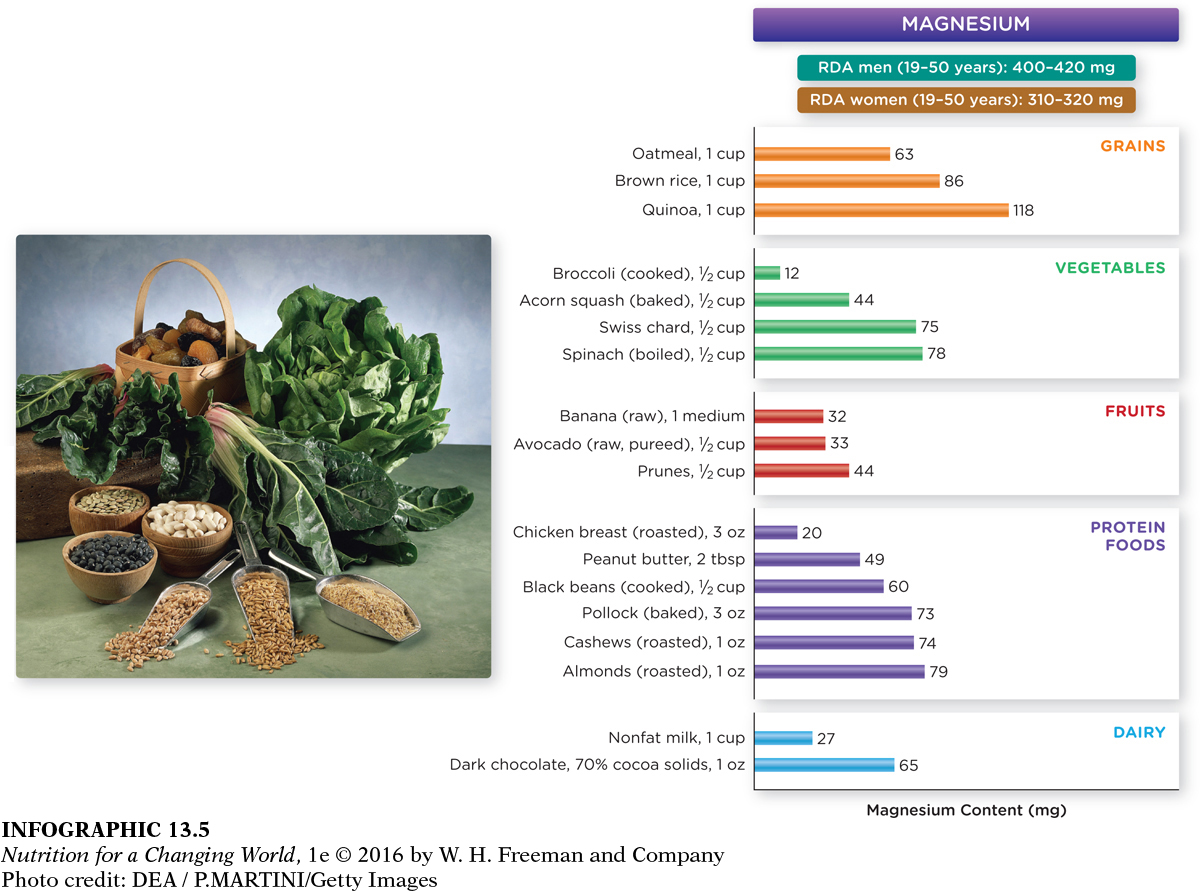

Magnesium (Mg) is a cofactor in more than 300 chemical reactions in the body. An adult body contains about 25 grams of magnesium, most of it—

Approximately 60% of American adults do not consume the recommended intake level of magnesium, but outright deficiency symptoms are rare, because the kidneys limit excretion when intake is low and the body may absorb more. However, low intakes of magnesium are a risk factor for osteoporosis. Marginal or moderate magnesium deficiencies may also increase the risk of atherosclerosis, cancer, diabetes, and hypertension. There is ongoing research about the role of magnesium in preventing and managing these disorders. Excess consumption from the diet is also rare, but toxicity can occur from supplement misuse. (INFOGRAPHIC 13.5)

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (P) is the second most abundant mineral in the body and is present in every cell of the body. It too plays a critical role in bone health and is an essential component of bone and cartilage, phospholipids, DNA, and RNA. It is also involved in energy metabolism, and a multitude of enzymes and other proteins depend upon phosphorus to regulate their activity. Phosphorus is important in the maintenance of proper acid-