ZINC

Zinc (Zn) is required for the function of perhaps more proteins in the body than any other mineral. Research indicates that zinc binds to about 10% (~2,800) of all proteins in the body, including more than 900 enzymes. Zinc functions as a co-

Although zinc deficiencies serious enough to produce readily identifiable symptoms are uncommon in the United States, it is estimated that about 12% of the population is at risk of deficiency. Some groups, including alcoholics, vegetarians, and the elderly, are particularly at risk of a zinc deficiency. Alcohol reduces zinc absorption and increases zinc excretion in the urine, while phytates in whole grains and legumes, which are dietary staples among vegetarians, inhibit the mineral’s absorption. Zinc status in the elderly may be compromised because of reduced food intake and impaired absorption resulting from low gastric acid production.

Mild to moderate zinc deficiency can cause impaired immune function, appetite loss and weight loss, delayed sexual maturation, and slowed growth. Severe zinc deficiency results in hair loss, diarrhea, infertility in men, and impaired neurological and behavioral functions. Symptoms of zinc deficiency can mimic symptoms of other nutrient deficiencies and can occur along other deficiencies in part because zinc plays an important role in the proper functioning of many other nutrients.

The UL for zinc intake for men and women 19 years and older is 40 mg. Short-

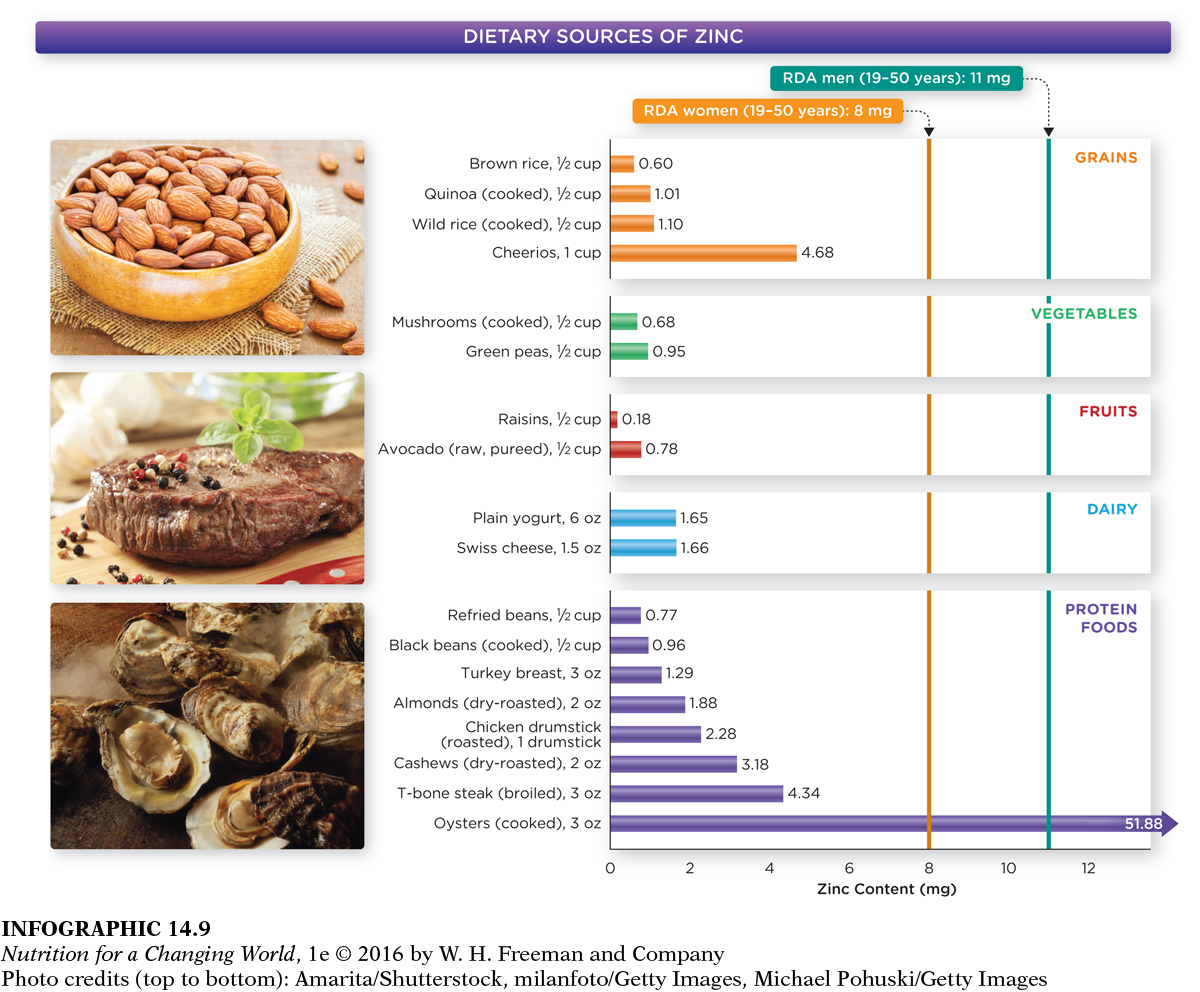

The recommended intake of zinc is 11 mg for men 19 years and older and 8 mg for women in the same age group. Since the body cannot store zinc, a regular daily intake is required to maintain adequate zinc status, although absorption does increase in the small intestine when intake is low. Because vegetarians absorb less zinc than nonvegetarians do, the Dietary Reference Intakes recommend that vegetarians and vegans consume twice as much zinc as nonvegetarians. Zinc is found in many foods but is most concentrated in meats, poultry, and certain types of seafood, such as oysters, which contain more zinc per serving than any other food. Fortified cereals, beans, and nuts also provide zinc, as do certain brands of cold lozenges and some over-