THE BIOLOGY OF HUNGER

Given energy’s central role in sustaining life, it is not surprising that obtaining and storing energy has a complex physiological regulation. Our bodies will let us know when we are hungry, and when we have eaten enough (if we pay attention). Through this complex physiological control system, which involves a constant dialogue between our brains and our gastrointestinal tract, we are able to obtain and maintain sufficient energy stores to power our activities.

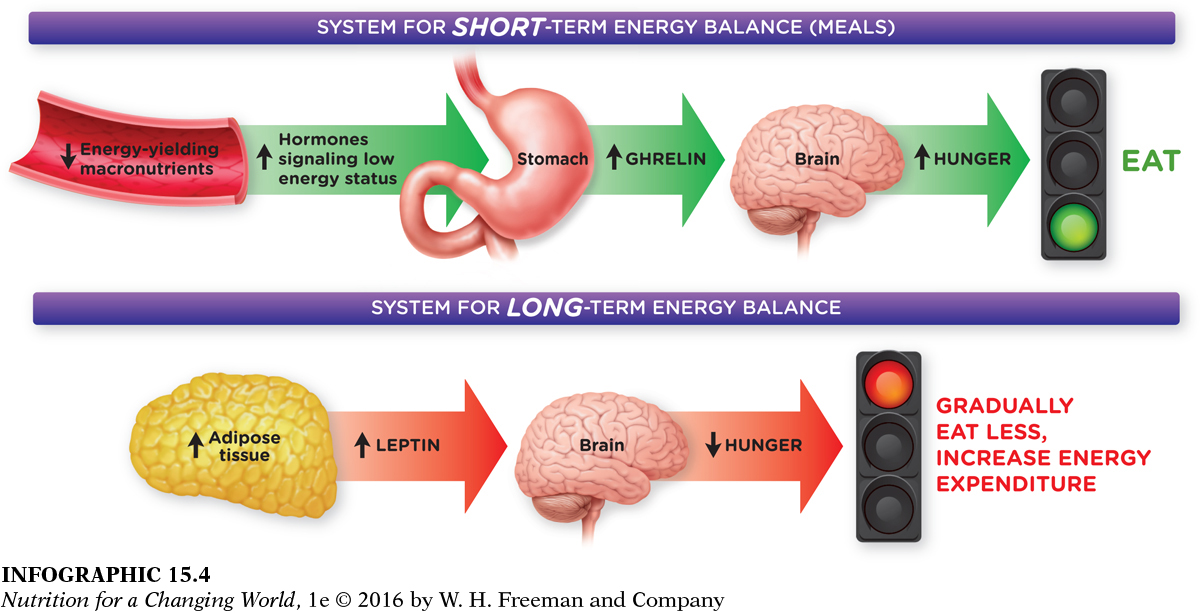

There are two different ways of regulating energy balance and food intake, a short-

Hormones participate in energy balance

GHRELIN a hormone that stimulates hunger before meals

When we haven’t eaten for a while, our stomach begins to grumble. That grumbling is a sign that a hormone called ghrelin is racing into action. Ghrelin, nicknamed the “hunger hormone,” is a 28–

SATIATION the sense of fullness while eating that leads to the termination of a meal

SATIETY the effect that a meal has on our interest in food after and between meals and when we feel hungry again

Satiation is the process that leads to the termination of a meal and refers to the sense of fullness that we feel while eating. Satiety is the effect that the meal has on our interest in food after a meal; it operates in the interval between meals and affects when we feel hungry again. The primary factors affecting these two processes are gastric distention—

Importantly, calories in beverages appear to bypass mechanisms of satiation. A number of studies have demonstrated that soft-

LEPTIN a hormone produced by adipose tissue that plays a role in body fat regulation and long-

Over the long term, energy balance is affected by a hormone called leptin. Leptin is produced primarily by adipose (fat) tissue. Its circulating concentration is closely associated with total body fat. When fat stores increase, more leptin is produced. The leptin level increase in the blood acts on the brain to suppress hunger, and increases energy expenditure to avoid excess weight gain. (INFOGRAPHIC 15.4)

If leptin suppresses hunger, and fat people have more leptin, then why do people ever become obese? It turns out that obese individuals have higher levels of circulating leptin than lean individuals, but they seem to be resistant to the effects of leptin. Thus, they don’t experience the same suppressed hunger or increased expenditure of energy. Some evidence suggests that a high-

Hunger and appetite

HUNGER the biological impulse that drives us to seek out and consume food to meet our energy needs

APPETITE a desire for food for reasons other than, or in addition to, hunger

In addition to the internal cues that regulate energy balance, there are also many environmental cues that influence food intake and energy expenditure. It is critical to differentiate between hunger and appetite. Hunger is the biological impulse that drives us to seek out food and consume it to meet our energy needs. Appetite, however, is often viewed as the liking and wanting of food for reasons other than, or in addition to, hunger. Appetite is often a product of sensory stimuli (the sight or smell of appealing foods) and the perceived pleasure we will experience as we satisfy our appetite and eat the desired food.

Most of us live in an environment in which we are surrounded by a plethora of palatable foods that are readily accessible. Hunger is certainly not the only reason (and perhaps not the dominant one) that motivates us to eat on many occasions. (See Chapter 19 to learn more about determinants of eating behavior.) We often eat because it is pleasurable to do so. Furthermore, food manufacturers spend billions of dollars in research designing foods that will trigger our “bliss point”—with just the right balance of salt, fat, and sugar that we find nearly irresistible. Similarly, large sums of money are spent marketing these products to us. We are often surrounded by cues (such as advertisements) that stimulate our appetite and make us not only want to eat, but to eat specific foods—

We also eat for many other reasons, such as in response to stress, boredom, and difficult emotions. All of these reasons for eating can, to some degree, override the satiety signals that are designed to keep us in energy balance.

So is overconsumption of food the cause of our obesity epidemic? Are we simply being goaded into eating more food than we used to, and paying the price in wider waistlines? Levine and his colleagues think that there is more to this story than just an increase in energy intake.