A NEAT CAUSE OF WEIGHT GAIN

We all know people who seem to be able to eat anything they wish and never gain weight. Likewise, there are those who “merely have to look at food” to put on pounds. It turns out there is scientific support for these subjective observations. Studies that have looked at weight gain in response to overfeeding have shown that people vary greatly in how much fat they accumulate. The biological mechanism that allows some individuals to resist weight gain more than others, however, has not been identified.

In 1999, Levine set out to solve the mystery. He and a team of researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, recruited 16 nonobese adults (12 men and 4 women from 25 to 36 years of age). These individuals underwent measures of body composition and energy expenditure before and after eight weeks of supervised overfeeding by 1,000 kcal per day.

The researchers found that fat gain varied tenfold among individuals in the study, ranging from a gain of only 0.36 kg to a gain of 4.23 kg (1 kg = 2.2 lb). Why was the weight gain so disparate? One obvious possibility is each person expended a different amount of energy.

Understanding energy expenditure

TOTAL ENERGY EXPENDITURE (TEE) the total amount of energy expended through basal metabolism, thermic effect of food, and activity energy expenditure

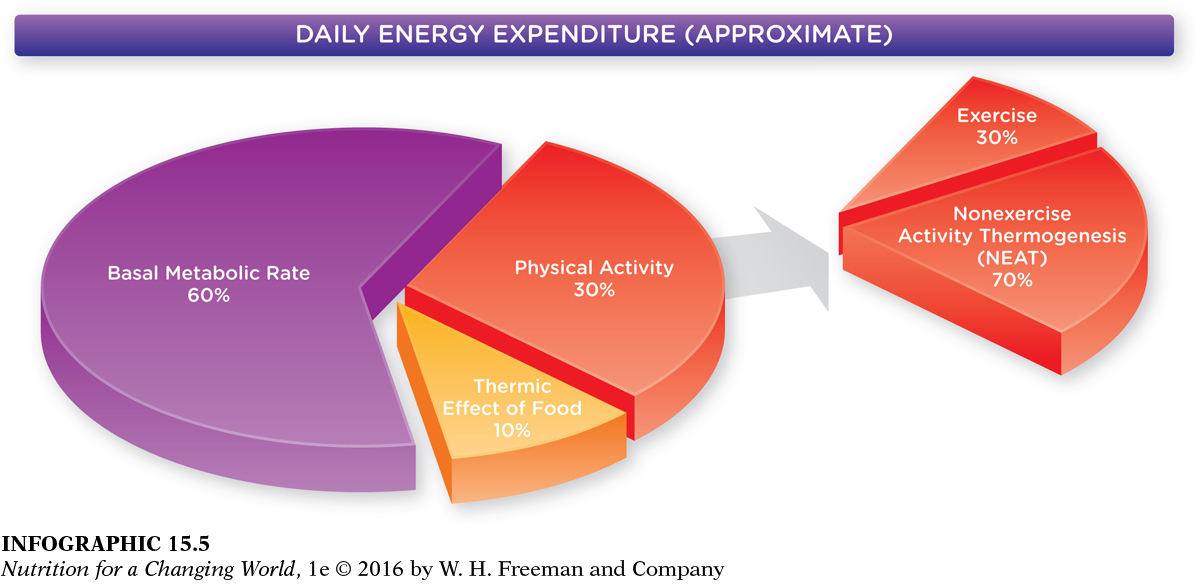

A person’s total energy expenditure (TEE) can be divided into three main components: (1) basal metabolism, (2) the thermic effect of food, and (3) activity energy expenditure.

BASAL METABOLISM the energy expenditure required to maintain the essential functions that sustain life

Basal metabolism is the energy expenditure required to maintain the essential functions that sustain life. This energy is required for the chemical reactions in our cells, the maintenance of muscle tone, and the work done by our heart, lungs, brain, liver, and kidneys—

THERMIC EFFECT OF FOOD (TEF) the energy needed to digest, absorb, and metabolize nutrients in food

ACTIVITY ENERGY EXPENDITURE (AEE) the amount of energy expended in physical activity per day

Thermic effect of food (TEF) is the energy needed to digest, absorb, and metabolize nutrients in our food. TEF is generally equivalent to 10% of the energy content of the food ingested and does not vary greatly between people. Activity energy expenditure (AEE) is the amount of energy individuals expend in physical activity per day, both planned and spontaneous. It includes all the energy expended in the contraction of skeletal muscles to move our body and to maintain posture (sitting or standing versus lying down). AEE is the most variable component of TEE. (INFOGRAPHIC 15.5)

Question 15.4

If you increase your energy expenditure by 500 kcal per day, how many more calories would you need to consume to stay in energy balance?

If you increase your energy expenditure by 500 kcal per day, how many more calories would you need to consume to stay in energy balance?

If your daily energy expenditure increased by 500 kcal a day, you would need to consume 500 additional kcal a day to stay in energy balance.

Fat-free mass and basal metabolic rate

BASAL METABOLIC RATE (BMR) the amount of energy expended in basal metabolism over a fixed period, typically expressed as kcal per day

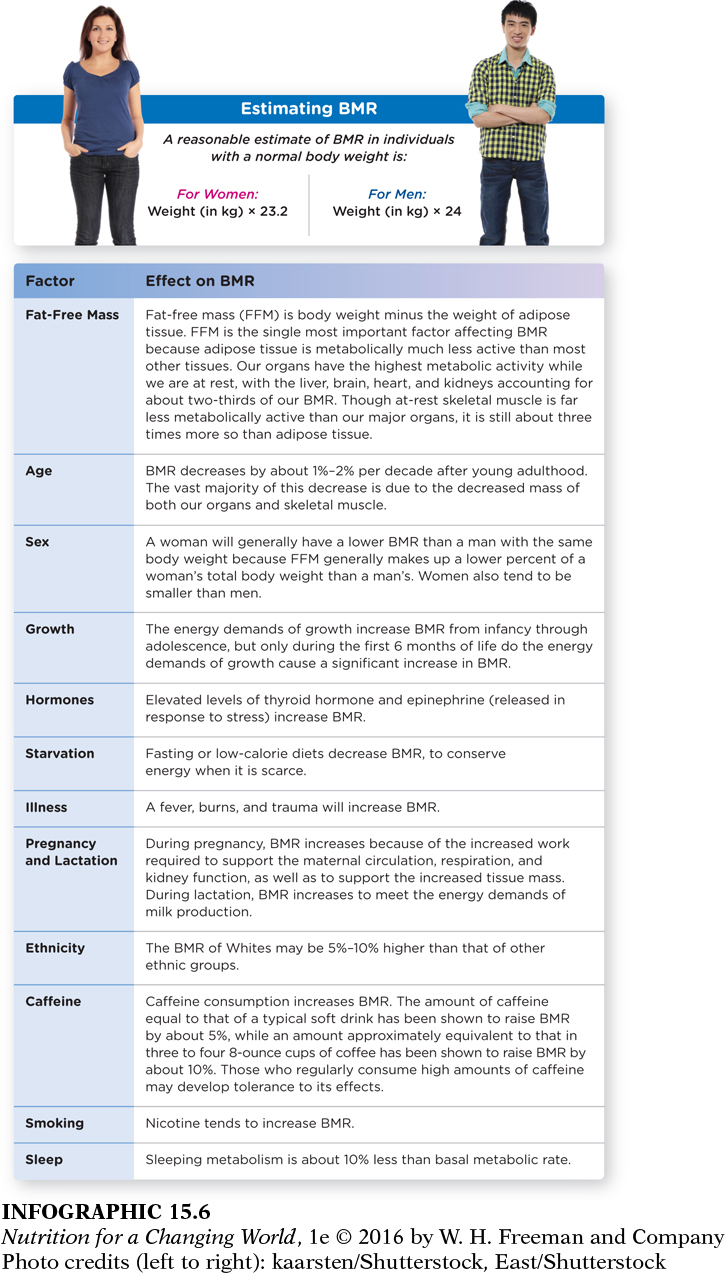

Though people can and do vary in the amount of energy expended by their basal metabolism, having a “low metabolism” is not a widespread cause of obesity. Nearly all of the variation in basal metabolism from person to person is accounted for by individual differences in fat-

Question 15.5

What two factors affect BMR primarily because they strongly influence a person’s FFM?

What two factors affect BMR primarily because they strongly influence a person’s FFM?

Age and sex affect basal metabolic rate because they influence fat-

In Levine’s study, he found only very minor increases in BMR and TEF in his study participants, which was not enough to account for the tenfold variance in fat gain among them. By contrast, levels of physical activity varied markedly between study participants. Interestingly, intentional exercise was not the crucial difference in activity level.

NEAT (NONEXERCISE ACTIVITY THERMOGENESIS) the energy expended for everything we do that is not sleeping, eating, or sportslike exercise

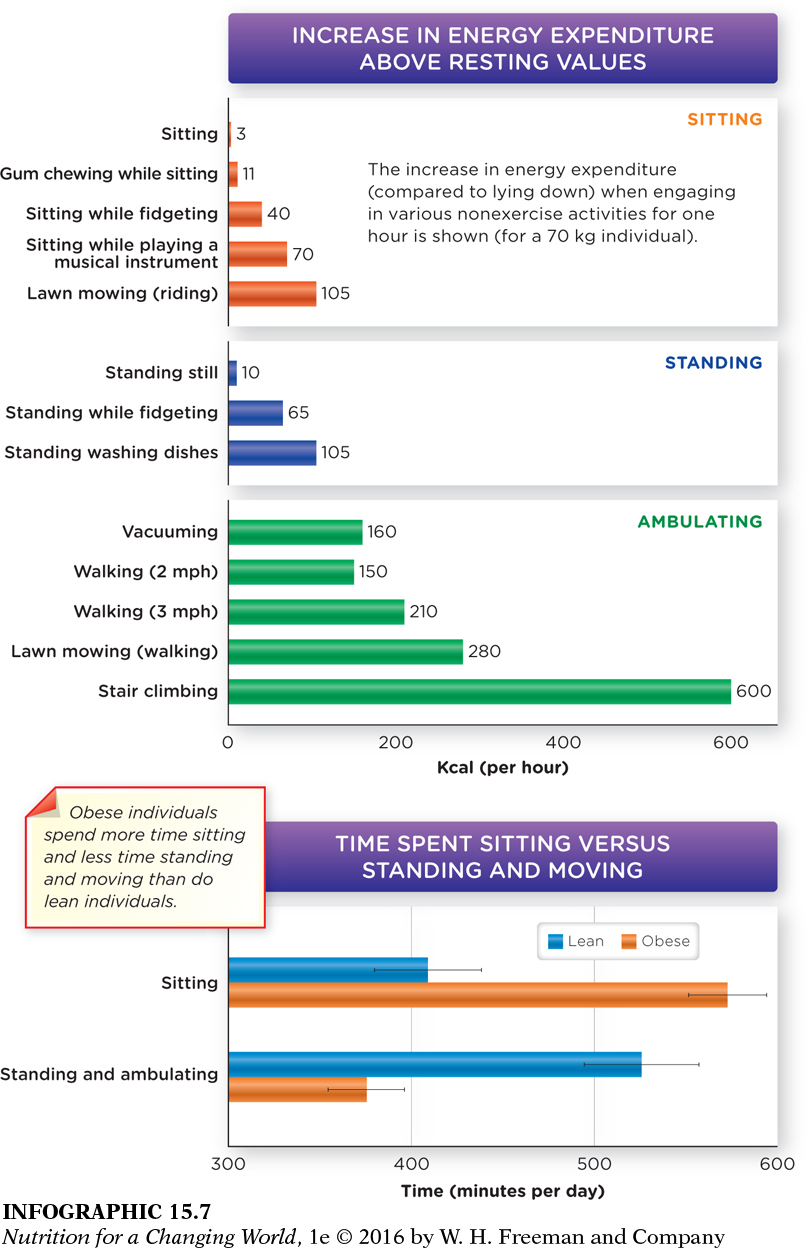

Levine designed his study in such a way that exercise was kept at a constant and minimum level across all study participants. Therefore, the differences in physical activity were principally non–

NEAT includes all the activities of daily living, such as household chores, yard work, shopping, occupational activity, walking the dog, and playing a musical instrument. It also includes the energy expended to maintain posture and spontaneous movements such as fidgeting, pacing, and even chewing gum. In other words, NEAT encompasses all the activities we do as part of daily living, separate from planned, intentional exercise like going for a run, taking an aerobics class, or hopping on an exercise bike.

In Levine’s study, NEAT varied greatly among individuals (fewer than 100 kcal to more than 700 kcal per day). More important, changes in NEAT were inversely correlated with changes in weight gain. In other words, NEAT proved to be the principal mediator of resistance to fat gain in these individuals. (INFOGRAPHIC 15.7)

Question 15.6

Describe three or four changes that you can make to your daily routine to increase your nonexercise activity thermogenesis.

Describe three or four changes that you can make to your daily routine to increase your nonexercise activity thermogenesis.

Many activities can increase NEAT, including walking instead of driving a car whenever possible; standing or walking during phone calls; taking the stairs instead of elevators and escalators; routinely completing house and yard chores, such as making your bed and sweeping the sidewalk; and shopping for and cooking meals instead of ordering takeout.

Question 15.7

How many additional calories would you expend by climbing stairs for one minute compared with riding in an elevator for the same time?

How many additional calories would you expend by climbing stairs for one minute compared with riding in an elevator for the same time?

A 70-

Next, Levine wanted to know if NEAT plays a role in obesity. Do lean and obese people differ in their levels of NEAT, for example? To get at this question, Levine and his colleagues recruited 20 healthy volunteers who were self-

To measure NEAT, Levine and colleagues devised a novel way to track activity levels in test volunteers. They built a special kind of underwear outfitted with electronic sensors that detect movement. The undergarments were built to allow people to wear them essentially all the time—

From those measurements, they can then calculate how many calories a person expends per day. Over the 10-

The bottom line? Obese people sit on average 2.25 hours longer than their leaner counterparts. Moreover, this tendency seems to be innate: Lean individuals sit the same amount of time even after they are forced to gain weight, and obese individuals sit the same amount of time even after they are forced to lose it.

What does all this have to do with obesity? Levine thinks that it’s not only that people are eating more than they did a few decades ago, but also that we have been “seduced” (his word) by our environment into expending less energy by sitting more.