Chapter Introduction

17

NUTRITION FOR PREGNANCY, BREASTFEEDING, AND INFANCY

391

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Discuss recommendations and rationale for appropriate weight gain during pregnancy (Infographic 17.3)

Define small for gestational age (SGA) and describe consequences of a small-

for- gestational- age birth weight (Infographic 17.4) Compare energy and nutrient needs during pregnancy and lactation and compare to recommendations for non-

pregnant women (Infographic 17.5) Identify foods and beverages that should be avoided during pregnancy and explain why they should be avoided (Infographic 17.6)

Identify at least five benefits infants derive from breastfeeding (Infographic 17.8)

Describe appropriate growth patterns in the first two years of life (Infographic 17.10)

Discuss timing and rationale for the introduction of solid foods into an infant’s diet (Infographic 17.11)

Few sights are more distressing to a midwife than that of an unresponsive newborn. But this was the situation Judith Mercer, a certified nurse-

392

Mercer was awed by what she had seen. She vowed, right then and there, to study what she had witnessed and understand why and how the umbilical cord might have saved that baby boy. “That baby affected the whole second half of my lifetime,” she says. Mercer went back to school, got a PhD, and as a clinical professor of nursing at the University of Rhode Island, she has dedicated her life to studying the benefits of what is known as delayed cord clamping. Usually, within seconds of a birth, obstetrical care providers clamp the umbilical cord connecting mother to baby, severing the blood flow between them. As Mercer’s research has shown, however, delaying the clamping of the umbilical cord by several minutes can provide benefits. Not only does the cord continue to provide blood and oxygen to the newborn in the event of a trauma, but it also increases the baby’s stores of iron—

393

In March 2013, the Cochrane Collaboration, a nonprofit international consortium funded in part by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, analyzed the results of 15 clinical trials—

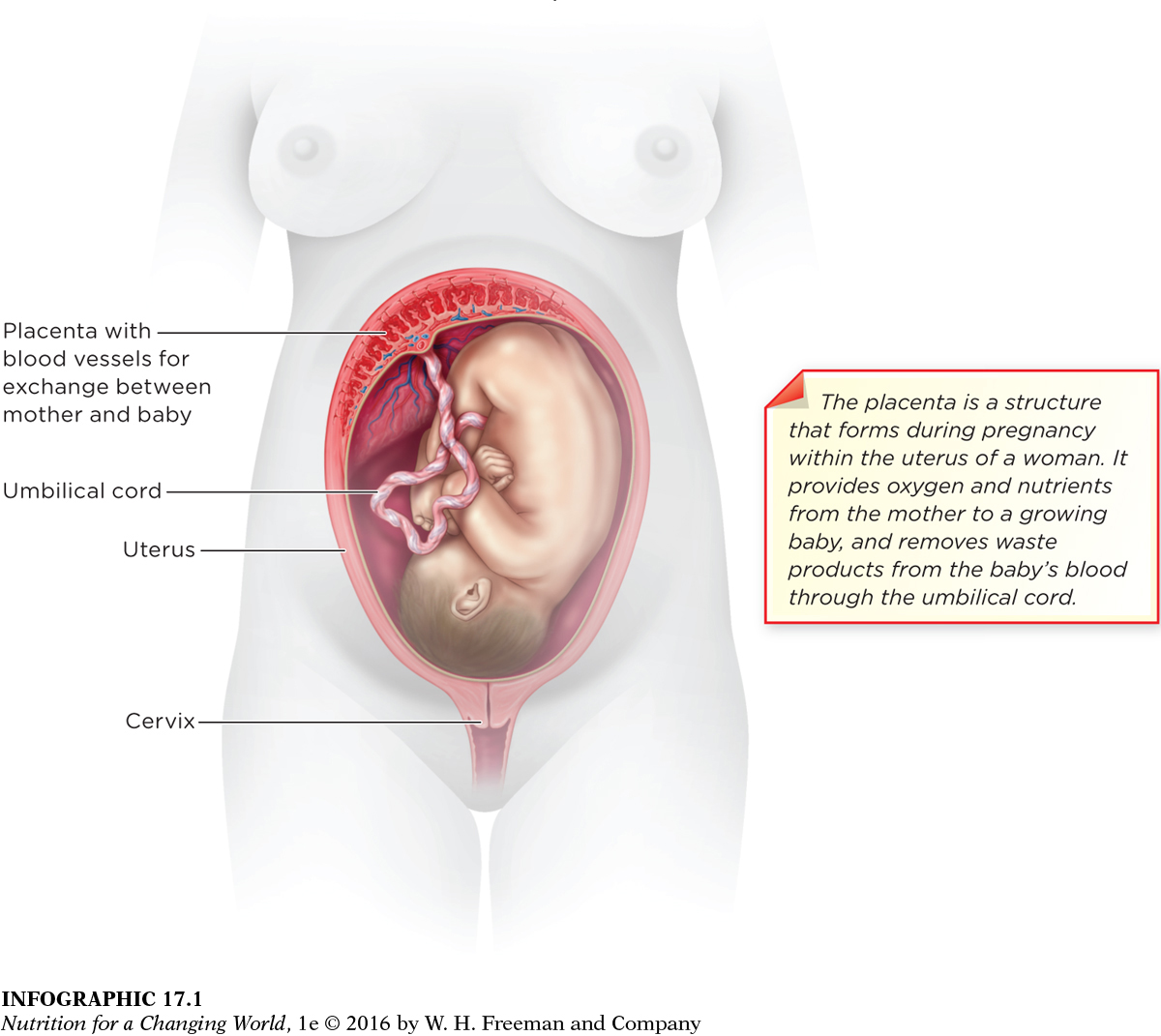

UMBILICAL CORD a ropelike structure that supplies the fetus with nutrients and oxygen and removes waste

PREGNANCY the condition of being pregnant, encompassing the time from fertilization through birth

■ ■ ■

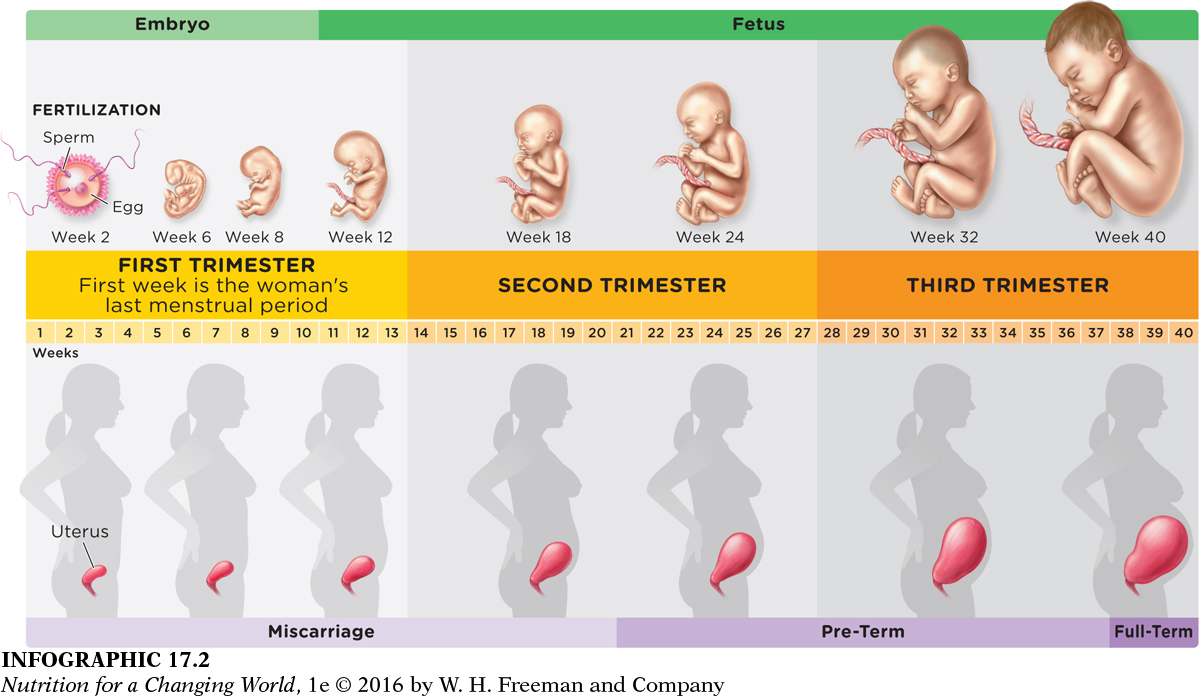

Although Mercer’s research points to the importance of the umbilical cord after birth, its primary purpose is to supply nutrients and oxygen to a developing baby during pregnancy, the period from fertilization to birth. Pregnancy begins when a woman’s egg is fertilized by a sperm, forming a zygote that develops into an embryo and then a fetus.

UTERUS a muscular organ that holds the developing fetus

PLACENTA organ within the uterus that allows for exchange between maternal and fetal circulations, via the umbilical cord

Starting about five weeks after fertilization, the umbilical cord develops and then supplies the fetus with nutrients and oxygen and removes waste until it is clamped after birth. The fetus is carried in a fluid-

394

EMBRYO the developing human during the first two to eight weeks of gestation

FETUS the developing human from eight weeks of gestation until birth

Between two and eight weeks after fertilization, as the organs and vital systems begin to develop, a developing human is referred to as an embryo. At the tenth week of pregnancy (eight weeks after fertilization), the developing human is called a fetus, and its organs mature as it puts on significant amounts of weight (from less than one ounce to between about seven and eight pounds at birth).

GESTATION the time during which the embryo develops in the uterus—

TRIMESTER one-

The entire period of development from fertilization to birth is called gestation. Full-