NUTRITION SCIENCE IN ACTION

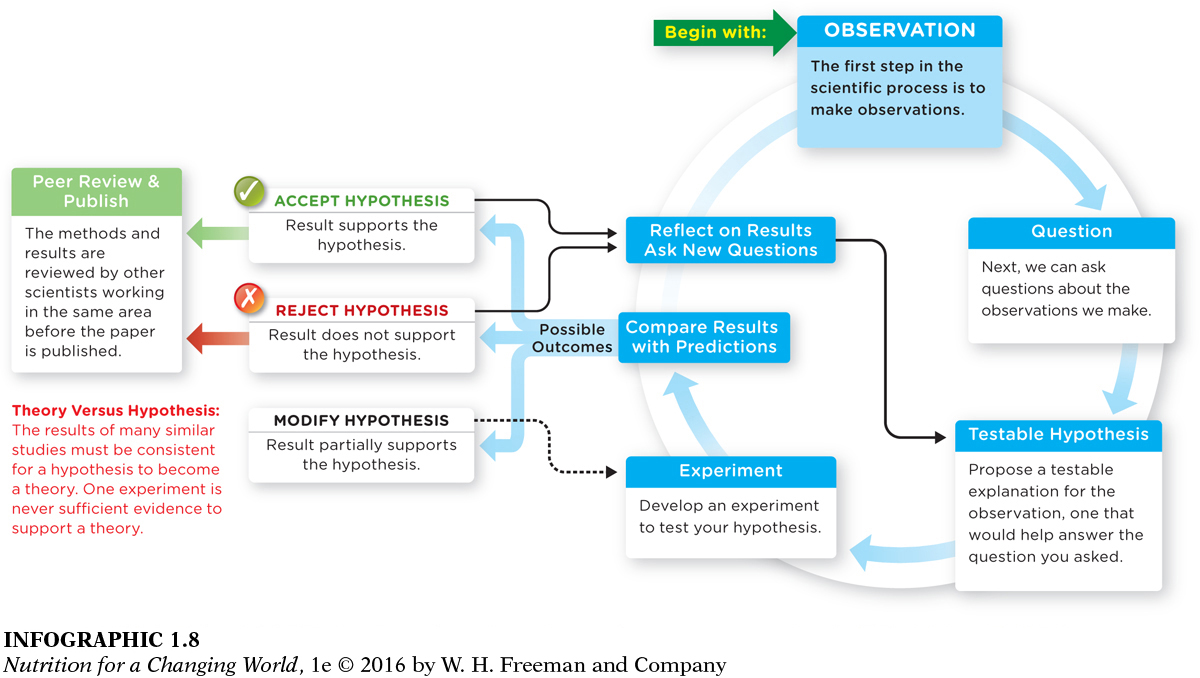

To begin his investigation, Waterland, like all scientists, followed the scientific method. (INFOGRAPHIC 1.8) He started with an observation and then identified a question or problem to investigate further. In his case, the observation that diet in pregnancy changed mouse babies’ coat color and overall health led him to wonder how that occurred. So he talked to his boss at the time, Randy Jirtle at Duke University in North Carolina, and said he wanted to repeat the mouse study, and try to explain this transmission from generation to generation.

SCIENTIFIC METHOD

a specific series of steps that involves a hypothesis, measurements and data gathering, and interpretation of results

Question 1.8

Explain why the following hypothesis is not suitable for the design of an experiment: "Dietary factors affect the risk of cancer."

Explain why the following hypothesis is not suitable for the design of an experiment: "Dietary factors affect the risk of cancer."

The hypothesis "Dietary factors affect the risk of cancer" is not suitable for the design of an experiment because there is no way to develop an experiment to test it. To accept or reject the hypothesis, all possible dietary factors would need to be examined. Instead, the hypothesis should identify a specific dietary factor and a specific type of cancer in a specific population.

Forming a hypothesis

Waterland came up with a testable hypothesis, which is a proposed explanation for an observation that can be tested through experimentation. Based on the previous findings, Waterland hypothesized that supplementing the diet in pregnant mice affected mouse babies’ coat color and overall health, so his hypothesis maintained that supplementing the diet of pregnant mice with specific nutrients would increase the frequency of the healthier brown-

Conducting an experiment

Next, Waterland completed the experiment stage of the scientific method. He repeated the mouse experiment, feeding some pregnant mice a supplemented diet, and obtained the same results. Moms who ate the extra nutrients had more babies with brown fur, which previous research had found were at lower risk of obesity and other diseases than those with yellow fur. After performing DNA analyses he found that the supplements were directly responsible for these epigenetic changes. “When I first saw those results that was when I felt just, ‘Wow, we really have something here.’” As a final step in the scientific method, Waterland published his findings in a scientific journal, so that his findings could became another core source of evidence supporting the effect of food on genes—

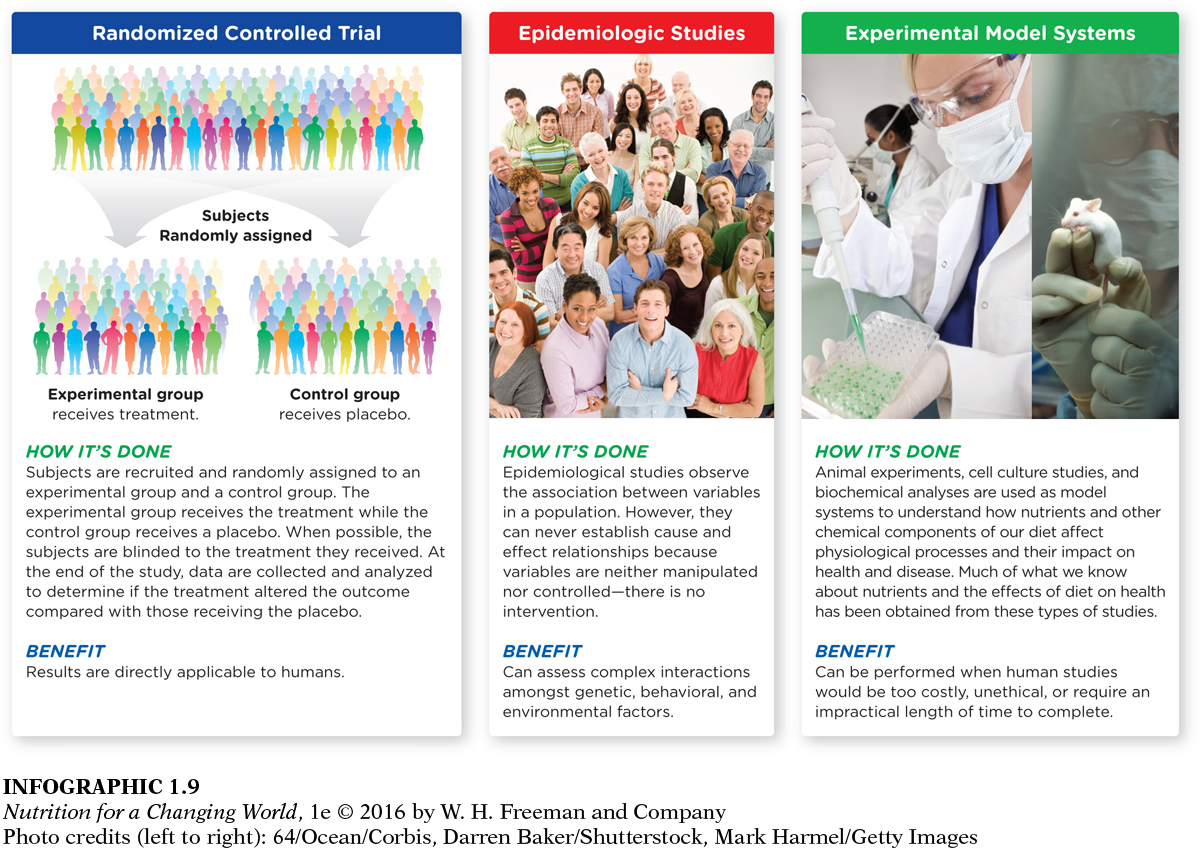

The study contained many of the important elements of a research paper. It had a control group, or a group of pregnant mice that received a healthy diet that did not contain any extra supplementation. Waterland then compared the results from the control group with those from mice in the experimental or treatment group, which received the supplemented diet, to determine that the supplemented diet did produce important epigenetic changes.

In other studies, such as those that look at the effect of medications, people in the control group receive a placebo drug, or one that contains no active properties. The purpose of the placebo is to eliminate the placebo effect, in which people feel better simply because they take a pill, and therefore have an expectation that they will feel better. To eliminate the placebo effect, it is also critical that people do not know what treatment they are receiving—

PLACEBO EFFECT

apparent effect experienced by a patient in response to a “fake” treatment due to the patient’s expectation of an effect

Question 1.9

An experimental protocol requires that a nutrient deficiency be induced to assess how this affects memory. What is the most appropriate study design to use to address this question?

An experimental protocol requires that a nutrient deficiency be induced to assess how this affects memory. What is the most appropriate study design to use to address this question?

An animal experiment is the most appropriate study design to use when the protocol requires that a nutrient deficiency be induced.

Analyzing the results

Because Waterland randomly assigned pregnant mice to receive either the control diet or the supplemented diet, and made sure the mice were the same in every other way, he could determine that the supplements caused the change in the patterns of chemical modification. Other studies, however, have to rely on correlational evidence. For instance, if Waterland had asked moms who had already given birth to recall if they had taken a prenatal vitamin during their pregnancies, then measured if there were any epigenetic changes in their babies, he might have seen a correlation, but he could never say whether the supplements caused any epigenetic changes. Moms who voluntarily choose to take a vitamin might also exercise more, drink more water, or have a higher socioeconomic status—

Although Waterland is quick to emphasize that the results of his experiment only apply to mice, it is now clear that epigenetic modifications are critical factors affecting the development of many human diseases. The mouse coat color experiment, along with the Dutch famine experiment, have “absolutely affected the way we think about nutrition,” says Patrick Stover, PhD, director of the division of nutritional sciences at Cornell University. “Some people seem to eat whatever they want, and never gain weight. This has always been the case in nutrition—