A BRIEF HISTORY OF FOOD SAFETY IN AMERICA

FOOD SAFETY the policies and practices that apply to the production, handling, preparation, and storage of food in order to prevent contamination and foodborne illness

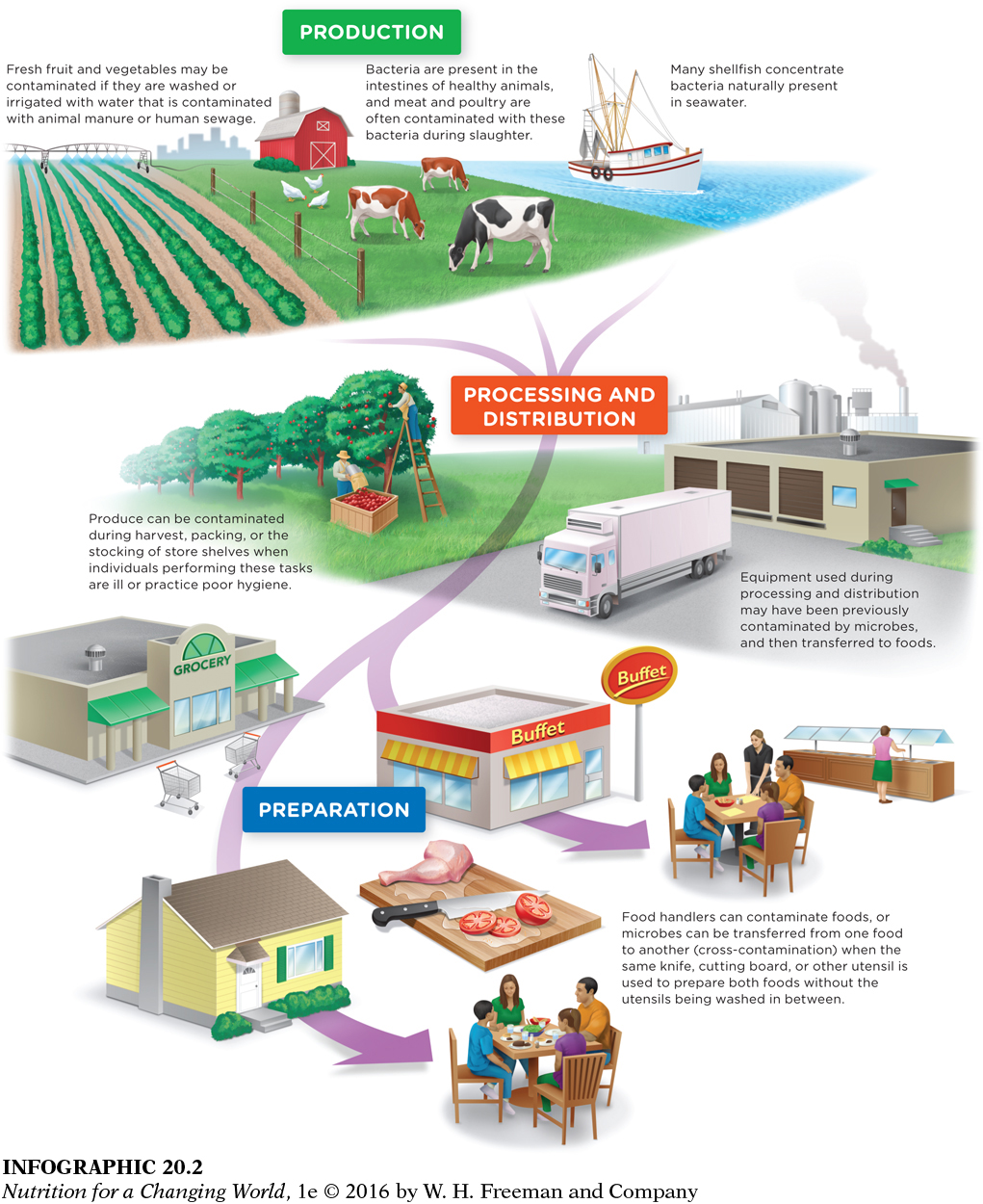

In the contemporary United States, food safety is ensured by an overlapping system of rules, regulations, and practices that preserve the quality of food and prevent contamination with foodborne pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses. The system we have in place today recognizes that the safety of food can be compromised at any point from production to consumption otherwise known as “farm to fork.” (INFOGRAPHIC 20.2)

Question 20.2

What should you do with your fresh produce before you eat it, even if it has a rind or peel?

What should you do with your fresh produce before you eat it, even if it has a rind or peel?

All fresh produce should be washed before consumption.

Most Americans take it for granted that the food they buy in the supermarket is “safe” to eat, but not many know how that safety is ensured, and even fewer realize just who is responsible for protecting them.

Prior to the early twentieth century, food products (and drugs) in this country were largely unregulated. At a time when more and more Americans were moving away from farms, and buying food in the marketplace, they also had no guarantees about what they were actually eating. There was no monitoring or control over how food was handled from the field to the shelves or bins from which it was sold. It was not uncommon for milk to be “preserved” with formaldehyde, hams to be adulterated with borate, and babies’ “soothing syrups” to be laced with morphine.

Food safety advocates had been arguing for years that something needed to be done to protect consumers from hazardous contaminants in food and unsafe food production and handling practices, but it was not until 1905 that the proper incentive for change was reached. That incentive came from a controversial book—

There would be meat stored in great piles in rooms; and the water from leaky roofs would drip over it, and thousands of rats would race about on it…. These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together … there were things that went into the sausage in comparison with which a poisoned rat was a tidbit. (The Jungle, Ch 14)

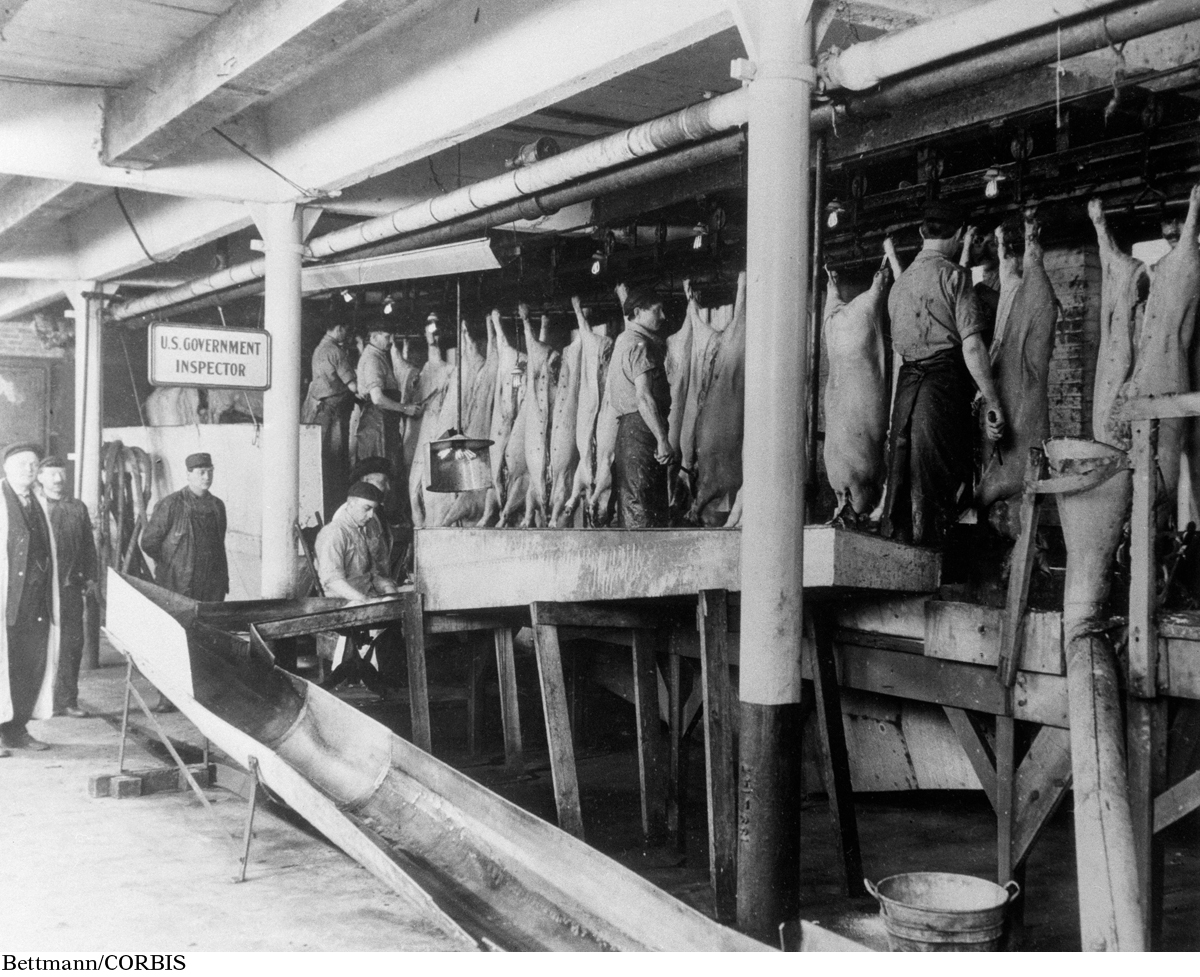

Citizens were appalled by what they read, as was U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who realized he needed to do something to clean up the mess. The revelations led directly to the passage of the nation’s first food safety legislations. The Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act were signed into law on the same day in 1906.

Under the Meat Inspection Act, government inspectors were given the authority to inspect carcasses in slaughterhouses. Using what became known as the “poke-

FDA historian Suzanne Junod, explains the far-

To this day, meat and poultry safety and food and drug safety are handled in different ways by different parts of the government. Meat inspection is handled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), while food (produce and packaged foods, for example) and drugs are the domain of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The poke-

These problems came to a head in the winter of 1993, when several hundred adults and children became severely ill and four children died after eating undercooked hamburgers from Jack in the Box fast-

FOODBORNE ILLNESS a largely preventable disease or condition caused by consumption of a contaminated food or beverage that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract

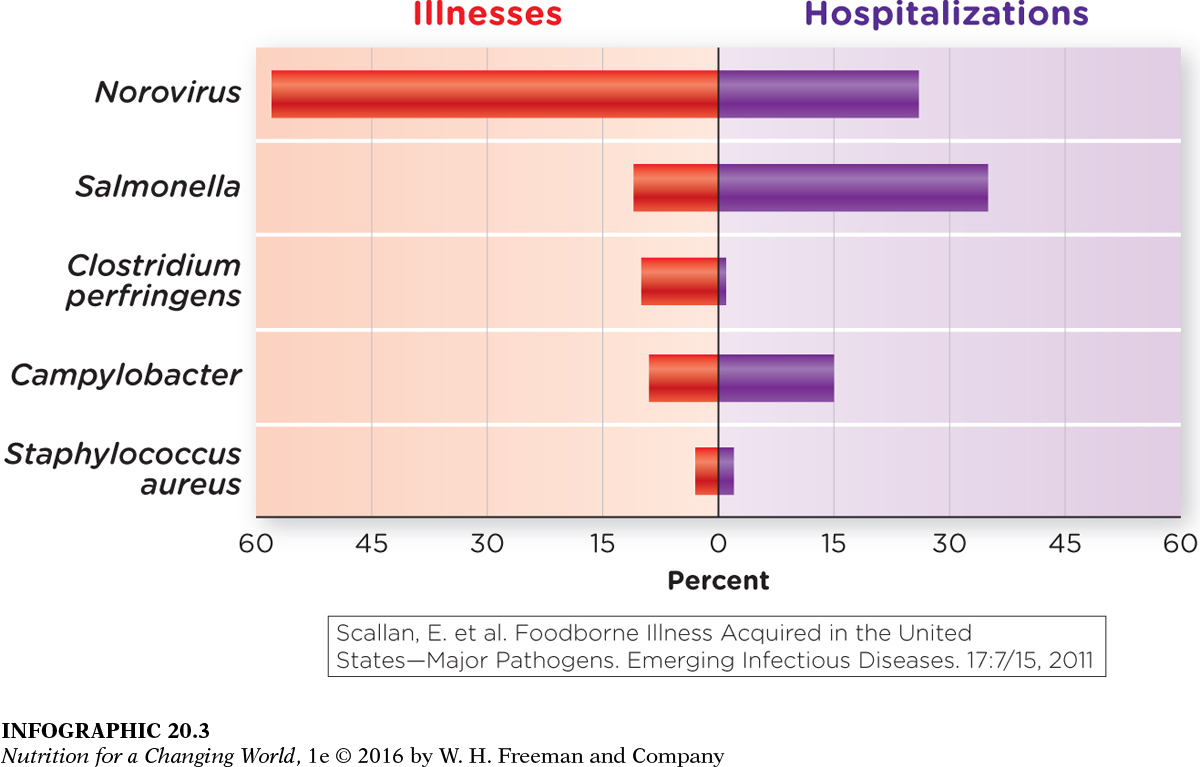

Foodborne illness (also known as food poisoning) is a very common, though largely preventable, condition in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control estimate that each year roughly 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) get sick from eating contaminated food. Of these, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die. Illness may result from consuming food that contains naturally occurring toxins, or food that is contaminated with toxic chemicals or pathogens (viruses, bacteria, or parasites). Although more than 250 foodborne diseases have been described, the most common are caused by just five pathogens: norovirus (a virus) and Salmonella, Clostridium perfringens, Staphylococcus, and Campylobacter (all bacteria). Although E. coli is not a leading cause of foodborne illness, it does cause the fifth highest number of hospitalizations due to foodborne illnesses. (INFOGRAPHIC 20.3)

Question 20.3

What pathogen causes the most severe illness?

What pathogen causes the most severe illness?

The norovirus pathogen causes the most illnesses.