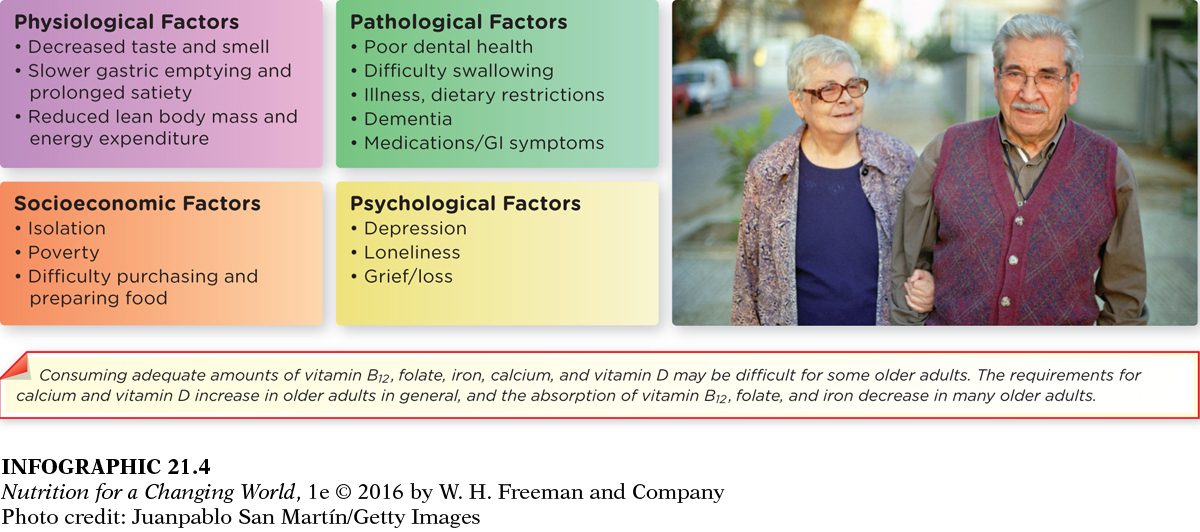

SPECIAL NUTRITIONAL CONCERNS FOR OLDER ADULTS

Despite this need for nutrient-dense foods, many older adults experience bodily changes that impair their ability or desire to meet these requirements. For example, many older people experience a decline in the senses of smell (olfaction) and taste (gustation), which can make food less palatable and therefore affect appetite because food just isn’t as appealing as it once was. Aging causes a more dramatic decline in the sense of smell than it does in taste. More than 60% of individuals between the ages of 65 and 80 have a major loss of smell, increasing to more than 75% of those who are older than 80 years. A reduction in mucus production that traps and transfers odorants, and a decrease in olfactory receptors and neurons that detect those odorants, are thought to be major factors leading to this age-related loss of smell. Diminished taste is caused by age-related decreases in the number, size, and sensitivity of taste buds.

With these declines in taste and smell, visual cues play an increasingly important role in stimulating appetite. It has been found that enhancing the dining room and the presentation of food increases food intake in nursing home residents. In addition to changes in taste and smell, loss of teeth and periodontal disease can compromise one’s ability to chew, which can also make obtaining adequate nutrition a challenge. (INFOGRAPHIC 21.4)

Question 21.4

Pick two of these factors and explain how and why they could result in decreased food intake.

Pick two of these factors and explain how and why they could result in decreased food intake.

Poor dental health may cause pain that makes eating unpleasant. Depression or isolation can suppress the appetite and reduce interest in eating. Mobility problems or poverty can limit access to transportation and foods.

Food and drug interactions

Nutritional status may be further compromised by the effects of medications on appetite and nutrient absorption. According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than 75% of older Americans (60 years and older) use two or more prescription drugs and 37% use five or more! This prevalence of drug use, both prescription and over-the-counter medications, combined with age-related alterations in physiological function, is a special concern for seniors. Healthcare providers must consider the implications of interactions among medications, dietary supplements, and food. Some drugs can affect the metabolism, absorption, or excretion of certain nutrients (for example, antacids can diminish the absorption of vitamin B12). And some foods can influence the action and effectiveness of medications. Fresh grapefruit and grapefruit juice, for example, contain a compound that decreases the breakdown of some drugs in the small intestine and liver, increasing their concentrations in the blood and enhancing their effects. And for individuals taking anticoagulant medications, atypical intake of vitamin K (an especially large serving of spinach or kale, for example) can decrease the medication’s effectiveness.

Changes in the digestive system

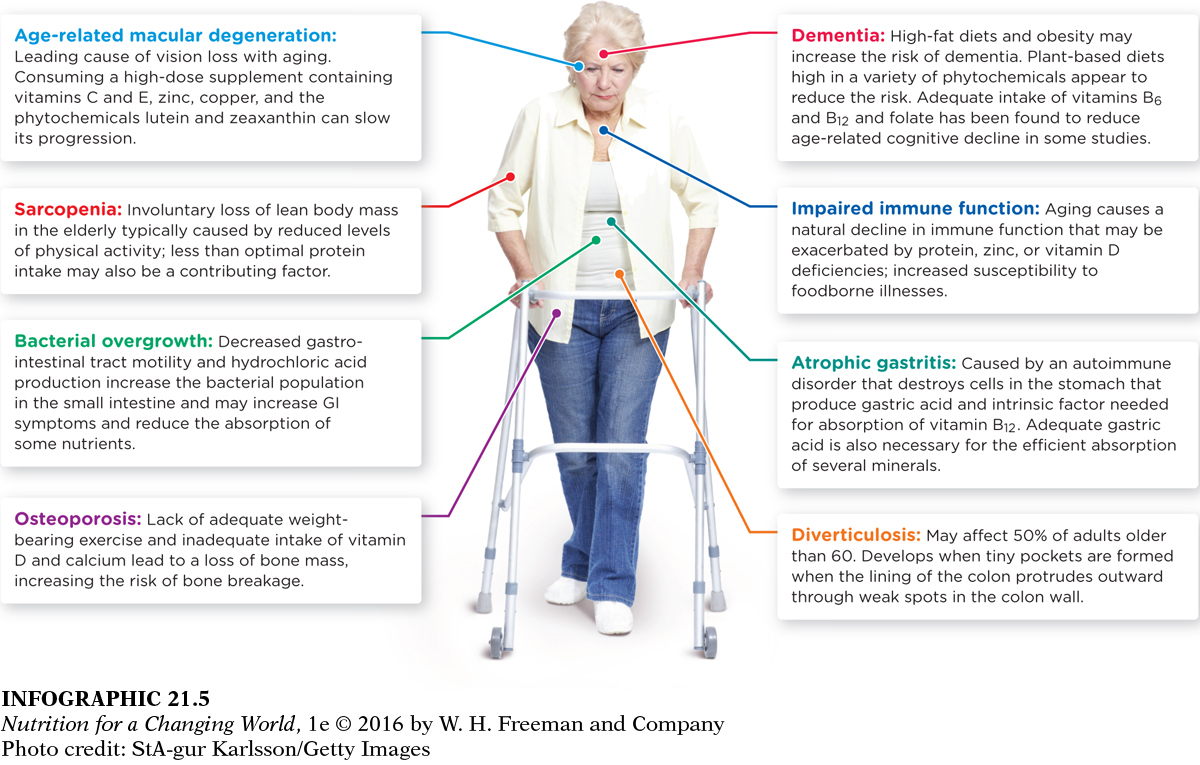

Age-related gastrointestinal changes may also occur, especially with regard to the bacterial composition of the gut, which can affect nutrient absorption. Diminished gastric acid secretion and slower motility in the small intestine can result in overgrowth of intestinal bacteria that interferes with absorption of nutrients. Reduced gastric acid production also causes malabsorption of naturally occurring vitamin B12, because gastric acid must release the vitamin from food proteins for it to be absorbed. It is estimated that at least 25% of those older than 60 years are deficient or marginally deficient in vitamin B12 and low B12 levels are associated with cognitive impairment and dementia. For this reason it is strongly recommended that the elderly receive their vitamin B12 from fortified foods or supplements. (INFOGRAPHIC 21.5)

Question 21.5

Which of these conditions may be prevented or delayed by proper nutrition earlier in life?

Which of these conditions may be prevented or delayed by proper nutrition earlier in life?

Dementia: High-fat diets and obesity may increase the risk of dementia. Plant-based diets high in a variety of phytochemicals appear to reduce the risk. Adequate intake of vitamins B6 and B12 and folate has been found to reduce age-related cognitive decline in some studies.

Diverticulosis: May affect 50% of adults older than 60 years; develops when the lining of the colon protrudes outward through weak spots in the colon wall, forming tiny pockets.

Sarcopenia: Involuntary loss of lean body mass in the elderly typically caused by reduced levels of physical activity; less-than-optimal protein intake may also be a contributing factor.

Osteoporosis: inadequate weight-bearing exercise and inadequate intake of vitamin D and calcium lead to a loss of bone mass, increasing the risk of bone breakage.

Reduced gastric motility also contributes, along with an age-related weakening of the colon wall and low fiber intake, to the development of diverticular disease, which affects approximately 50% of people by the age of 65 and higher incidence in older age groups. Changes in the digestive system can also reduce the production of stomach acid, which plays an important defensive role against the aging adult’s increased risk of foodborne illness (for more on foodborne illness see Chapter 20).

Because of all these things, the elderly are particularly vulnerable to malnutrition. And that, in turn, can compromise their ability to live long and prosper. It has been reported that about 60% of hospitalized adults 65 years or older and up to 85% of residents of nursing homes are malnourished. Elderly living in the community fare better, but many are still at risk for malnourishment, with slightly fewer than 40% being malnourished or at risk of malnourishment.

Depression and nutritional status

In addition to the varied physiological factors that affect the health and nutritional status of aging adults, psychosocial factors have an impact on their ability and motivation to obtain adequate and appropriate nourishment. Loss, loneliness, and lack of social support may result in increased risk of depression and suboptimal intake when eating alone. Research (and common sense) shows that individuals who are psychologically healthy, resilient, and have a sense of purpose in their lives are more likely to age successfully and experience better quality of life and overall health. This echoes the characteristics found in the Blue Zone populations.