PROTEIN TURNOVER AND NITROGEN BALANCE

The body needs amino acids from the diet to replace proteins that are lost when cells from our skin and those lining our gastrointestinal tract are shed. Dietary proteins are also needed to allow for the accumulation of additional body protein mass that occurs with growth, pregnancy, increasing muscle mass, and to support the growth of hair and nails, as well as for wound healing.

It is important to emphasize that proteins are synthesized as needed to support necessary body functions, so that consuming protein in excess of need will not increase the amount of proteins made. In other words, excess amino acids are not stored in our body as proteins. Excess amino acids are used as an energy source or stored as fat.

PROTEIN TURNOVER the continuous breakdown and resynthesis of proteins in the body

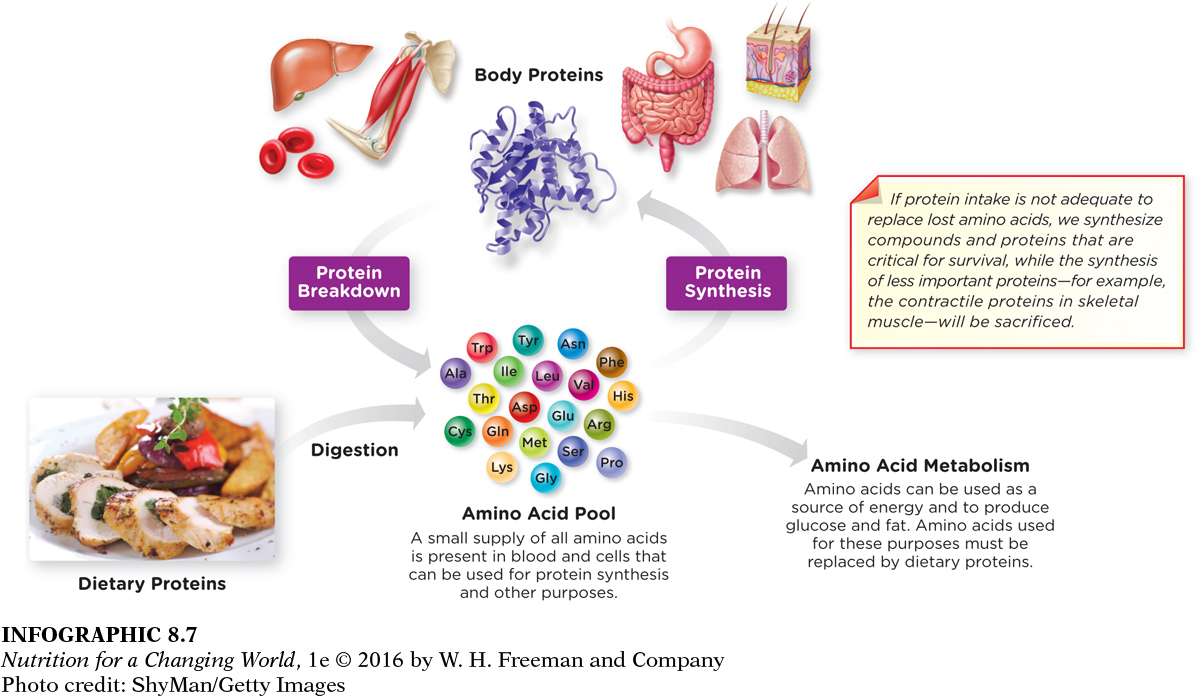

Proteins in the body are constantly being broken down and reassembled in a process called protein turnover. In fact, many of the amino acids used to make proteins don’t come from the food we eat each day, but are drawn from a pool of amino acids obtained from the breakdown of the body’s own proteins. Although we consume about 70 grams to 100 grams of protein daily, approximately 300 grams of proteins in cells and fluids throughout the body are broken down and resynthesized each day. Most of the amino acids released by the breakdown of body proteins are reused in the production of new proteins, but some amino acids are metabolized (chemically altered), which prevents them from being used for protein synthesis. These modified amino acids must be replaced with dietary proteins to provide sufficient amino acids to remake all the body proteins that were broken down. (INFOGRAPHIC 8.7)

Question 8.7

If amino acids generated from protein breakdown are reused for protein synthesis, why is it necessary for a nongrowing adult to eat any protein?

If amino acids generated from protein breakdown are reused for protein synthesis, why is it necessary for a nongrowing adult to eat any protein?

Amino acids can be used as a source of energy. Amino acids used in this way must be replaced by proteins supplied by the diet.

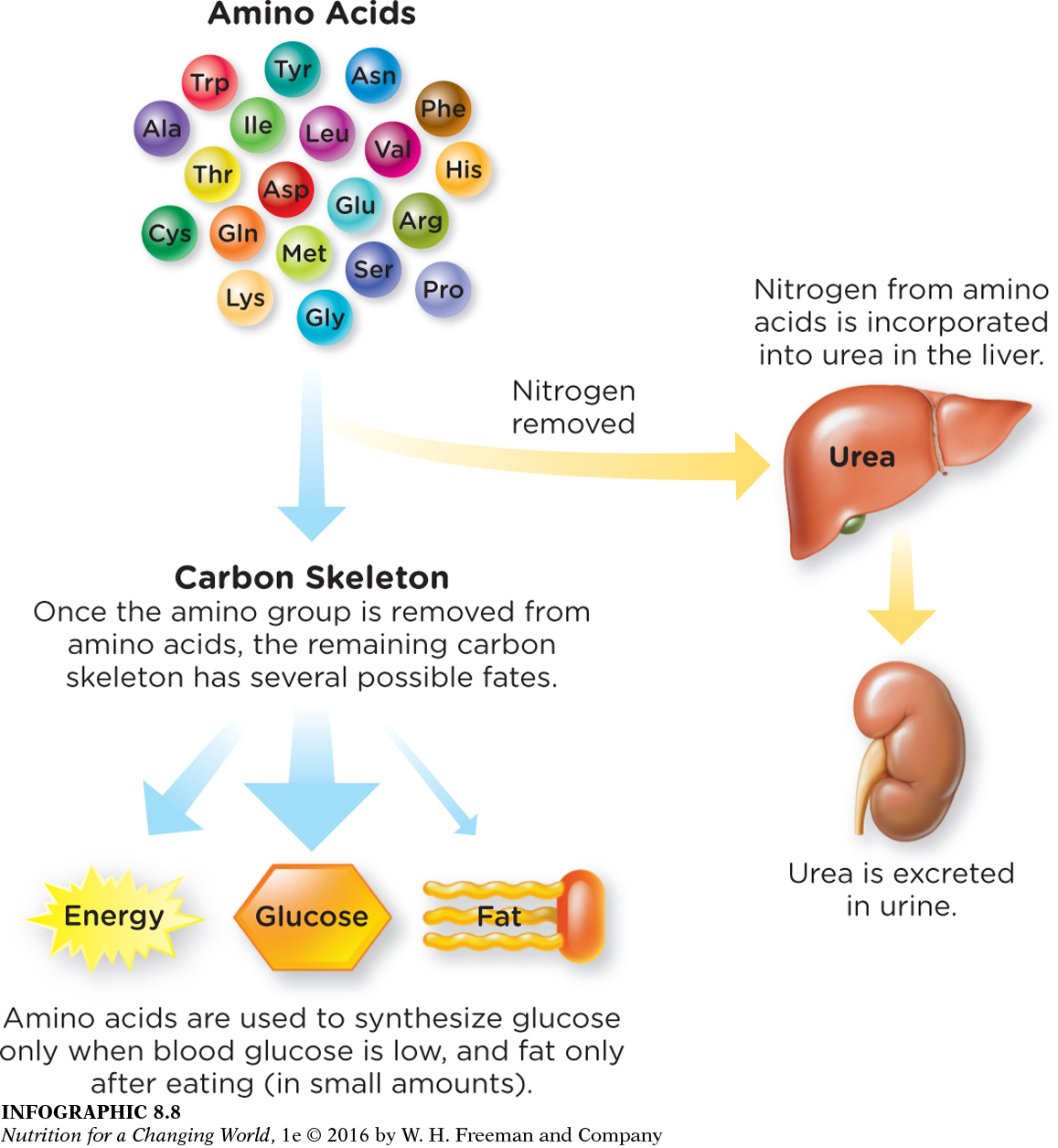

In many cases, the metabolism of amino acids requires that they first be stripped of their amino group, which leaves a carbon skeleton. This carbon skeleton is used primarily to synthesize glucose to maintain blood glucose levels when carbohydrate intake is low, or to a lesser degree, as a direct source of energy. In times of energy abundance, the body may also convert amino acids to fatty acids that are then stored in adipose tissue as triglycerides. (INFOGRAPHIC 8.8)

Question 8.8

What is a toxic waste product of amino acid breakdown that must be excreted from the body?

What is a toxic waste product of amino acid breakdown that must be excreted from the body?

Urea is a waste product of amino acid breakdown that must be excreted from the body.

When amino acids are used for energy, or to synthesize glucose or fatty acids, the amino group that was stripped off must be disposed of; otherwise it would accumulate in the body as ammonia, which is toxic. To prevent this, the liver converts ammonia to a less toxic substance called urea. Urea is then released into the blood, filtered by the kidneys, and excreted in urine.

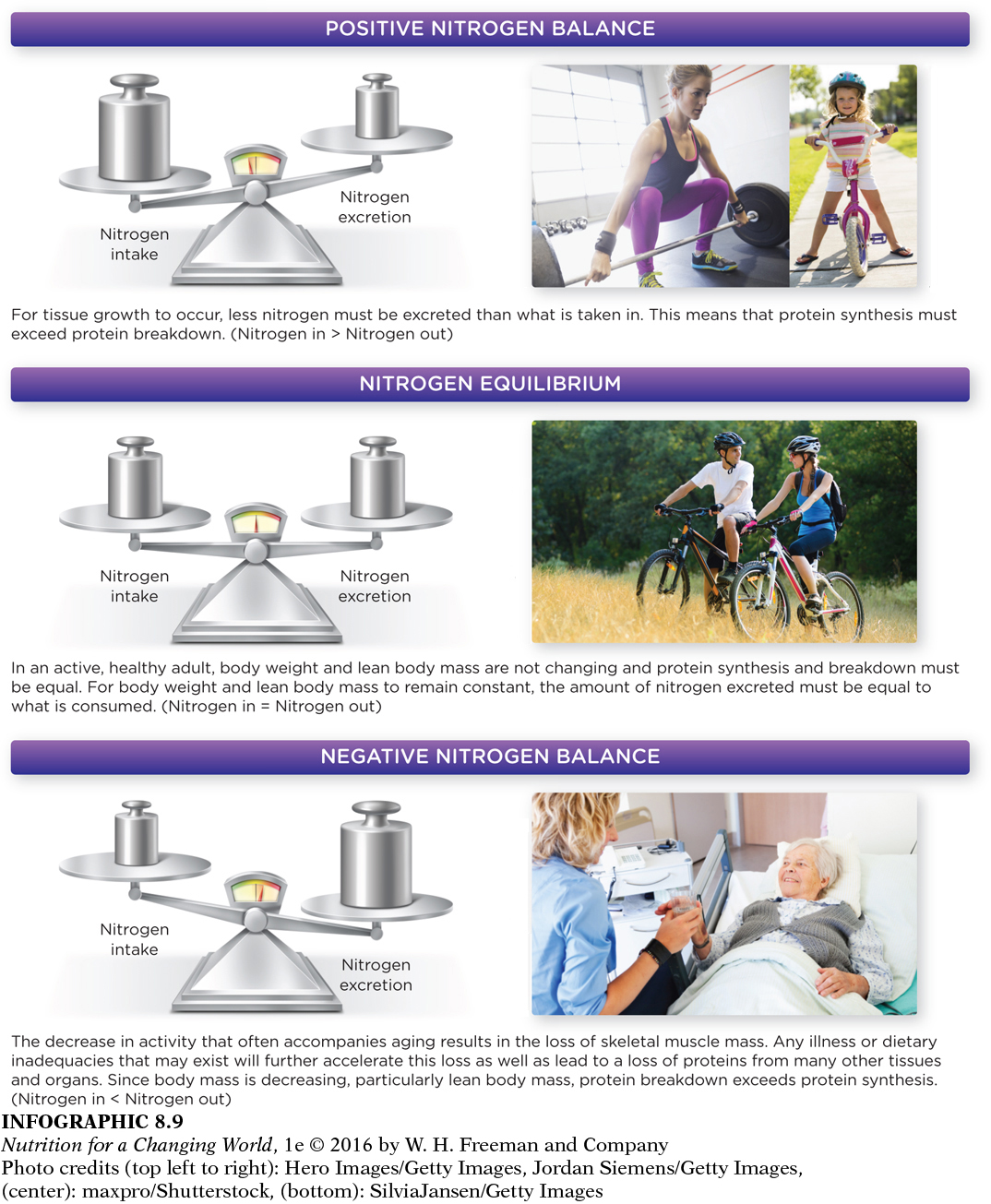

NITROGEN BALANCE a measure of nitrogen intake (primarily from protein) minus nitrogen excretion.

Scientists can measure urea in urine to study protein turnover in what is called a nitrogen balance study. As the name implies, nitrogen balance reflects if a body is gaining, losing, or maintaining protein. Protein intake is measured, as well as nitrogen output in urine and feces. Nitrogen losses from less significant sources (sweat, skin, hair, nails, breath, saliva, mucus, and other secretions) are estimated. As nongrowing, weight-

Question 8.9

What will be the nitrogen balance status of someone who is on a low-

What will be the nitrogen balance status of someone who is on a low-

Low-

■ ■ ■

Instead of lab-

This methodology has Lamont concerned. For one, when researchers repeat the experiments in the laboratory on the same athletes, they often get different results. That’s not a surprise, she notes—

However, many researchers and nutrition professionals believe extra amounts of protein can help highly competitive athletes who need to get maximum performance out of their bodies. How much protein athletes should eat is really two questions, says Stuart Phillips, PhD, professor of kinesiology at McMaster University in Ontario—