Daly and Bengali, Is It Still Worth Going to College?

This economic letter was originally posted by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco at www.frbsf.org, where it appeared on May 5, 2014.

IS IT STILL WORTH GOING TO COLLEGE?

MARY C. DALY AND LEILA BENGALI

1

Media accounts documenting the rising cost of a college education and relatively bleak job prospects for new college graduates have raised questions about whether a four-

Earnings Outcomes by Educational Attainment

2

A common way to track the value of going to college is to estimate a college earnings premium, which is the amount college graduates earn relative to high school graduates. We measure earnings for each year as the annual labor income for the prior year, adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index (CPI-

3

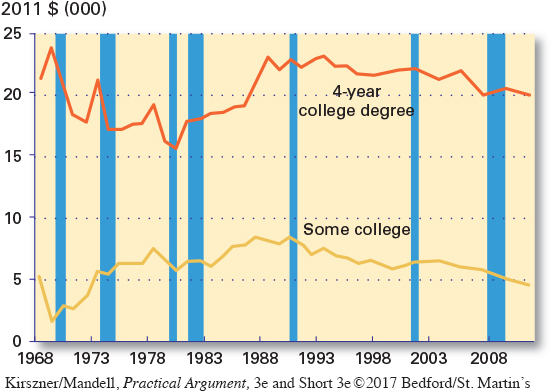

Figure 1 shows the earnings premium relative to high school graduates for individuals with a four-

Page 49

4

A potential shortcoming of the results in Figure 1 is that they combine the earnings outcomes for all college graduates, regardless of when they earned a degree. This can be misleading if the value from a college education has varied across groups from different graduation decades, called “cohorts.” To examine whether the college earnings premium has changed from one generation to the next, we take advantage of the fact that the PSID follows people over a long period of time, which allows us to track college graduation dates and subsequent earnings.

5

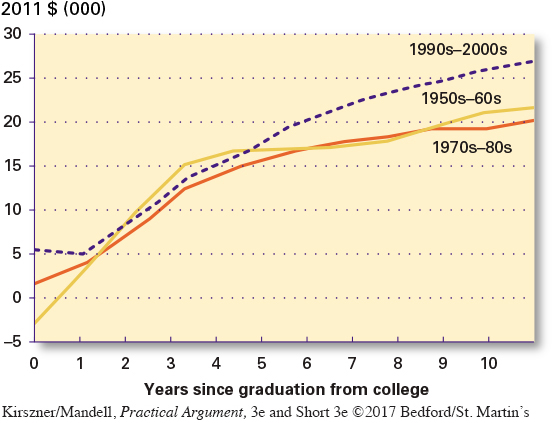

Using these data we compute the college earnings premium for three college graduate cohorts, namely those graduating in the 1950s–

Page 50

6

Figure 2 shows that the college earnings premium has risen consistently across cohorts. Focusing on the most recent college graduates (1990s–

7

The figure also shows that the gap in earnings between college and high school graduates rises over the course of a worker’s life. Comparing the earnings gap upon graduation with the earnings gap 10 years out of school illustrates this. For the 1990s–

8

Of course, some of the variation in earnings between those with and without a college degree could reflect other differences. Still, these simple estimates are consistent with a large and rigorous literature documenting the substantial premium earned by college graduates (Barrow and Rouse 2005, Card 2001, Goldin and Katz 2008, and Cunha, Karahan, and Soares 2011). The main message from these and similar calculations is that on average the value of college is high and not declining over time.

9

Page 51

Finally, it is worth noting that the benefits of college over high school also depend on employment, where college graduates also have an advantage. High school graduates consistently face unemployment rates about twice as high as those for college graduates, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. When the labor market takes a turn for the worse, as during recessions, workers with lower levels of education are especially hard-

The Cost of College

“Although the value of college is apparent, deciding whether it is worthwhile means weighing the value against the costs of attending.”

10

Although the value of college is apparent, deciding whether it is worthwhile means weighing the value against the costs of attending. Indeed, much of the debate about the value of college stems not from the lack of demonstrated benefit but from the overwhelming cost. A simple way to measure the costs against the benefits is to find the breakeven amount of annual tuition that would make the average student indifferent between going to college versus going directly to the workforce after high school.

11

To simplify the analysis, we assume that college lasts four years, students enter college directly from high school, annual tuition is the same all four years, and attendees have no earnings while in school. To focus on more recent experiences yet still have enough data to measure earnings since graduation, we use the last two decades of graduates (1990s and 2000s) and again smooth our estimates by using three-

12

We calculate the cost of college as four years of tuition plus the earnings missed from choosing not to enter the workforce. To estimate what students would have received had they worked, we use the average annual earnings of a high school graduate zero, one, two, and three years since graduation.

13

To determine the benefit of going to college, we use the difference between the average annual earnings of a college graduate with zero, one, two, three, and so on, years of experience and the average annual earnings of a high school graduate with four, five, six, seven, and so on years of experience. Because the costs of college are paid today but the benefits accrue over many future years when a dollar earned will be worth less, we discount future earnings by 6.67 percent, which is the average rate on an AAA bond from 1990 to 2011.

14

With these pieces in place, we can calculate the breakeven amount of tuition for the average college graduate for any number of years; allowing more time to regain the costs will increase our calculated tuition ceiling.

15

If we assume that accumulated earnings between college graduates and nongraduates will equalize 20 years after graduating from high school (at age 38), the resulting estimate for breakeven annual tuition would be about $21,200. This amount may seem low compared to the astronomical costs for a year at some prestigious institutions; however, about 90 percent of students at public four-

Page 52

16

Table 1 shows more examples of maximum tuitions and the corresponding percent of students who pay less for different combinations of breakeven years and discount rates. Note that the tuition estimates are those that make the costs and benefits of college equal. So, tuition amounts lower than our estimates make going to college strictly better in terms of earnings than not going to college.

| Breakeven age | ||

| 33 (15 yrs after HS) | 38 (20 yrs after HS) | |

| Accumulated earnings with constant annual premium | $880,134 | $830,816 |

| Discount rate | Maximum tuition (% students paying less) | |

| 5% | $14,385 (53– |

$29,111 (82– |

| 6.67%* | $9,869 (37– |

$21,217 (69– |

| 9% | $4,712 (0– |

$12,653 (53– |

Data from: PSID, College Board, and authors’ calculations. Premia held constant 15 or 20 years after high school (HS) graduation. Percent range gives lower and upper bounds of the percent of full-

17

Although other individual factors might affect the net value of a college education, earning a degree clearly remains a good investment for most young people. Moreover, once that investment is paid off, the extra income from the college earnings premium continues as a net gain to workers with a college degree. If we conservatively assume that the annual premium stays around $28,650, which is the premium 20 years after high school graduation for graduates in the 1990s–

Page 53

Conclusion

18

Although there are stories of people who skipped college and achieved financial success, for most Americans the path to higher future earnings involves a four-

References

Barrow, L., and Rouse, C.E. (2005). “Does college still pay?” The Economist’s Voice 2(4), pp. 1–

Card, D. (2001). “Estimating the return to schooling: progress on some persistent econometric problems.” Econometrica 69(5), pp. 1127–

College Board. (2013). “Trends in College Pricing 2013.”

Cunha, F., Karahan, F., and Soares, I. (2011). “Returns to Skills and the College Premium.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 43(5), pp. 39–

Dale, S., and Krueger, A. (2011). “Estimating the Return to College Selectivity over the Career Using Administrative Earnings Data.” NBER Working Paper 17159.

Goldin, C., and Katz, L. (2008). The Race between Education and Technology. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D., and Schaller, J. (2012). “Who Suffers During Recessions?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(3), pp. 27–

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

Why does the title of this essay include the word “still”? What does still imply in this context?

This essay is an “economic letter” from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and its language is more technical, and more math-

and business- oriented, than that of the other readings in this chapter. In addition, this reading selection looks somewhat different from the others. What specific format features set this reading apart from others in the chapter? Page 54

What kind of supporting evidence do the writers use? Do you think they should have included any other kinds of support—

for example, expert opinion? Why or why not? In paragraph 10, the writers make a distinction between the “value of college” and the question of whether a college education is “worthwhile.” Explain the distinction they make here.

For the most part, this report appeals to logos by presenting factual information. Does it also include appeals to pathos or ethos? If so, where? If not, should it have included these appeals?