See the additional resources for content and reading quizzes for this chapter.

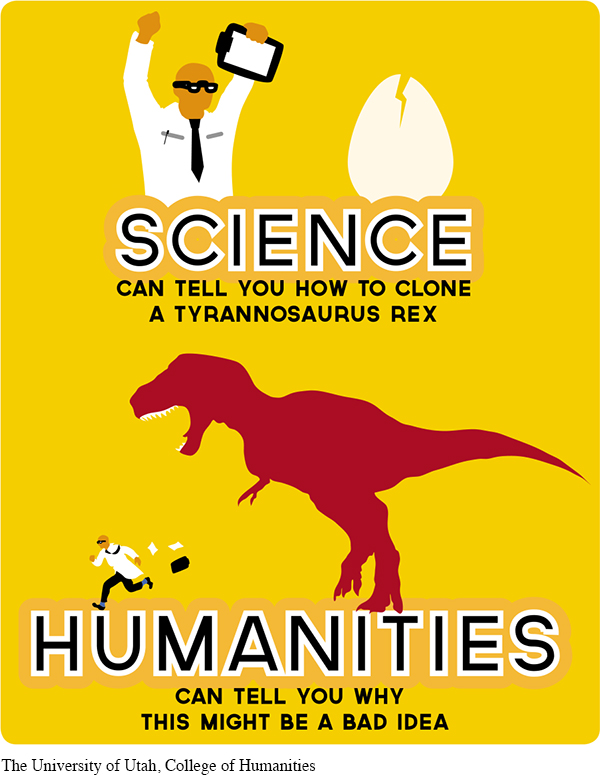

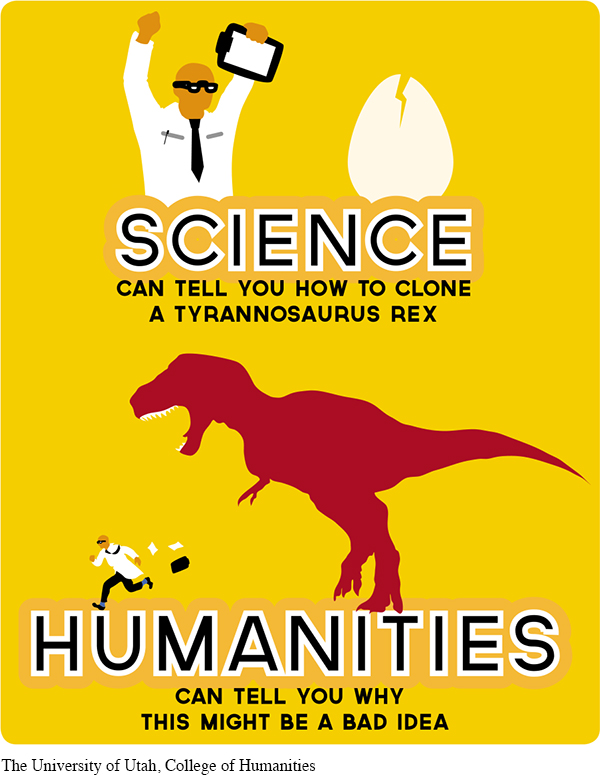

CHAPTER24CASEBOOK Does It Pay to Study the Humanities?

The University of Utah, College of Humanities

Page 727

At one time, students went to college to grow intellectually, to consider what they wanted to become, and to engage in the give-and-take of academic discourse. In the process, they could reexamine their ideas, develop new perspectives, and expand as thinkers and as human beings. Now, because students (and their parents) often have to take out loans to defray the high cost of tuition, they see a college education as an investment, not as a vehicle for intellectual growth. For this reason, they feel a great deal of pressure to ensure a return on their investment, and degrees in STEM subjects—an acronym that refers to courses in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math—offer this return because STEM graduates earn more money than liberal arts majors. As a result, students flock to STEM majors in increasing numbers, and the humanities—art, literature, music, and history—become less and less important on college campuses. What good, students ask, is Michelangelo when it comes to developing a newer, better Web app? How can an understanding of Tolstoy contribute to building a smarter smartphone?

Even though advocates for the humanities might concede that Tolstoy cannot help us to make a smartphone smarter, they would argue that all of us could benefit from reading Tolstoy. In addition, supporters of the humanities are concerned about what would be lost if we cut down on—or even eliminate—humanities courses. Although most people would agree that something is lost when we favor career skills over the humanities, they would have a difficult time pinpointing exactly what that “something” is. It is even harder to make the case for a liberal arts education when the average cost of a four-year degree is over $40,000 at a state school and over $135,000 at a private college.

In the following chapter, you will read some essays that address the question of whether it pays to study the humanities. In “The Economic Case for Saving the Humanities,” Christina H. Paxson, the president of Brown University, makes the point that society will benefit if it actively supports the humanities. In “Major Differences: Why Undergraduate Majors Matter,” Anthony P. Carnevale and Michelle Melton argue that colleges have an obligation to give students the information they need to make intelligent decisions about their majors and their lives. In “Is It Time to Kill the Liberal Arts Degree?” Kim Brooks questions whether colleges are downplaying the obstacles that liberal arts graduates face when they try to find full-time employment. Finally, in “Course Corrections,” Thomas Frank contends that in order to effectively defend the humanities, academics must first address the high cost of tuition.

Page 728