See the additional resources for content and reading quizzes for this chapter.

CHAPTER5Understanding Logic and Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Page 123

AT ISSUE

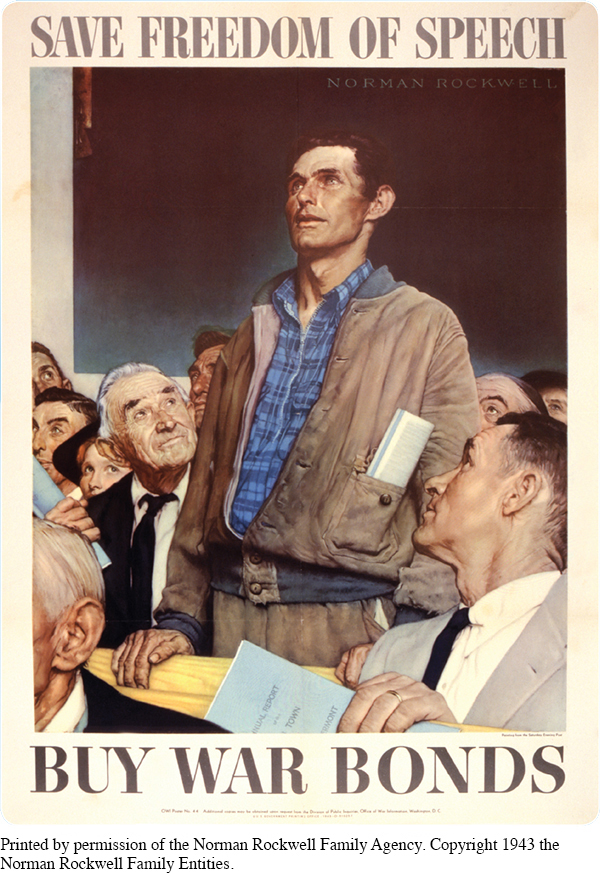

How Free Should Free Speech Be?

Ask almost anyone what makes a society free and one of the answers will be free speech. The free expression of ideas is integral to freedom itself, and protecting that freedom is part of a democratic government’s job: in a sense, this means that most people see free speech as one of the cornerstones of equality. Everyone’s opinion can, and indeed must, be heard.

But what happens when those opinions are offensive, or even dangerous? If free speech has limits, is it still free? When we consider the question abstractly, it’s very easy to say no. How can it be free if there are limits to how free it is, and who gets to decide those limits? It’s dangerous to give anyone that kind of authority. After all, there is no shortage of historical evidence linking censorship with tyranny. When we think of limiting free speech, we think of totalitarian regimes, like Nazi Germany.

But what happens when the people arguing for the right to be heard are Nazis themselves? In places like Israel and France, where the legacy of Nazi Germany is still all too real, there are some things you simply cannot say. Anti-

On American college campuses, free speech is often considered fundamental to a liberal education, and in many ways, encountering ideas that make you feel uncomfortable is a necessary part of a college education. But the question of free speech is easy to answer when it’s theoretical: when the issue is made tangible by racist language or by a discussion of a traumatic experience, it becomes much more difficult to navigate. For example, should African-

Page 124

Later in this chapter, you will be asked to think more about this issue. You will be given several sources to consider and asked to write a logical argument that takes a position on how free free speech should be.

The word logic comes from the Greek word logos, roughly translated as “word,” “thought,” “principle,” or “reason.” Logic is concerned with the principles of correct reasoning. By studying logic, you learn the rules that determine the validity of arguments. In other words, logic enables you to tell whether a conclusion correctly follows from a set of statements or assumptions.

Why should you study logic? One answer is that logic enables you to make valid points and draw sound conclusions. An understanding of logic also enables you to evaluate the arguments of others. When you understand the basic principles of logic, you know how to tell the difference between a strong argument and a weak argument—

Page 125

Specific rules determine the criteria you use to develop (and to evaluate) arguments logically. For this reason, you should become familiar with the basic principles of deductive and inductive reasoning—two important ways information is organized in argumentative essays. (Keep in mind that a single argumentative essay might contain both deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. For the sake of clarity, however, we will discuss them separately.)