Newstok, A Plea for Close Learning

This article was originally published in Liberal Education in the Fall 2013 issue.

A PLEA FOR CLOSE LEARNING

SCOTT L. NEWSTOK

1

What an exciting year for distance learning! Cutting-

2

Innovative assessment mechanisms let professors supervise their pupils remotely. All this progress was good for business, too. Private entrepreneurs leapt at the chance to compete in the new distance-

3

True, a few naysayers fretted about declining student attention spans and low course-

Page 237

“This should give us pause as we recognize that massive open online courses, or MOOCs, are but the latest iteration of distance learning.”

4

2013, right? Think again: 1885. The commentator quoted above was Yale classicist (and future University of Chicago President) William Rainey Harper, evaluating correspondence courses. That’s right: you’ve got (snail) mail. Journalist Nicholas Carr has chronicled the recurrent boosterism about mass mediated education over the last century: the phonograph, instructional radio, televised lectures. All were heralded as transformative educational tools in their day. This should give us pause as we recognize that massive open online courses, or MOOCs, are but the latest iteration of distance learning.

5

In response to the current enthusiasm for MOOCs, skeptical faculty (Aaron Bady, Ian Bogost, and Jonathan Rees, among many others) have begun questioning venture capitalists eager for new markets and legislators eager to dismantle public funding for American higher education. Some people pushing for MOOCs, to their credit, speak from laudably egalitarian impulses to provide access for disadvantaged students. But to what are they being given access? Are broadcast lectures and online discussions the sum of a liberal education? Or is it something more than “content” delivery?

“Close Learning”

6

To state the obvious: there’s a personal, human element to liberal education, what John Henry Newman once called “the living voice, the breathing form, the expressive countenance” (2001, 14). We who cherish personalized instruction would benefit from a pithy phrase to defend and promote this millennia-

7

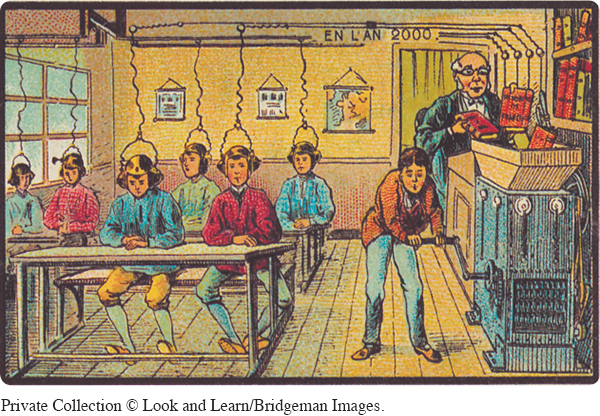

Techno-

Page 238

8

The old-

9

A Columbia University neuroscientist, Stuart Firestein, recently published a polemical book titled Ignorance: How It Drives Science. Discouraged by students regurgitating his lectures without internalizing the complexity of scientific inquiry, Firestein created a seminar to which he invited his colleagues to discuss what they don’t know. As Firestein repeatedly emphasizes, it is informed ignorance, not information, that is the genuine “engine” of knowledge. His seminar reminds us that mere data transmission from teacher to student doesn’t produce liberal learning. It’s the ability to interact, to think hard thoughts alongside other people.

10

In a seminar, a student can ask for clarification, and challenge a teacher; a teacher can shift course when spirits are flagging; a stray thought can spark a new insight. Isn’t this the kind of nonconformist “thinking outside the box” that business leaders adore? So why is there such a rush to freeze knowledge and distribute it in a frozen form? Even Coursera cofounder Andrew Ng concedes that the real value of a college education “isn’t just the content…. The real value is the interactions with professors and other, equally bright students” (quoted in Oremus 2012).

11

The business world recognizes the virtues of proximity in its own human resource management. (The phrase “corporate campus” acknowledges as much.) Witness, for example, Yahoo’s controversial decision to eliminate telecommuting and require employees to be present in the office. CEO Marissa Mayer’s memo reads as a mini-

12

Why do boards of directors still go through the effort of convening in person? Why, in spite of all the fantasies about “working from anywhere” are “creative classes” still concentrating in proximity to one another: the entertainment industry in Los Angeles, information technology in the Bay Area, financial capital in New York City? The powerful and the wealthy are well aware that computers can accelerate the exchange of information and facilitate “training,” but not the development of knowledge, much less wisdom.

13

Close learning transcends disciplines. In every field, students must incline toward their subjects: leaning into a sentence, to craft it most persuasively; leaning into an archival document, to determine an uncertain provenance; leaning into a musical score, to poise the body for performance; leaning into a data set, to discern emerging patterns; leaning into a laboratory instrument, to interpret what is viewed. MOOCs, in contrast, encourage students and faculty to lean back, not to cultivate the disciplined attention necessary to engage fully in a complex task. Low completion rates for MOOCs (still hovering around 10 percent) speak for themselves.

Page 239

Technology as Supplement

14

Devotion to close learning should not be mistaken for an anti-

15

Teachers have always employed “technology”—including the book, one of the most flexible and dynamic learning technologies ever created. But let’s not fixate upon technology for technology’s sake, or delude ourselves into thinking that better technology overcomes bad teaching. At no stage of education does technology, no matter how novel, ever replace human attention. Close learning can’t be automated or scaled up.

16

As retrograde as it might sound, gathering humans in a room with real time for dialogue still matters. As educators, we must remind ourselves—

17

What remains to be seen is whether we value this kind of close learning at all levels of education enough to defend it, and fund it, for a wider circle of Americans—

References

Firestein, S. 2012. Ignorance: How It Drives Science. New York: Oxford University Press.

Page 240

Newman, J. H. 2001. “What Is a University?” In Rise and Progress of Universities and Benedictine Essays, edited by M. K. Tilman, 6–

Oremus, W. 2014. “The New Public Ivies: Will Online Education Startups like Coursera End the Era of Expensive Higher Education?” Slate, July 17, http://www.slate.com/

Swisher, K. 2013. “‘Physically Together’: Here’s the Internal Yahoo No-

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR USING ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO ARGUMENT

What effect does Newstok want his introduction to have on readers? How can you tell? In your opinion, is his strategy successful?

In paragraph 5, Newstok asks whether an education “is something more than ‘content’ delivery.” What does he mean?

According to Newstok, what is “close learning” (para. 6)? What are its advantages over online education?

Where does Newstok address the major arguments against his position? How effectively does he refute them?

Use Toulmin logic to analyze Newstok’s essay, identifying the argument’s claim, its grounds, and its warrant. Does Newstok appeal only to logos, or does he also appeal to pathos and ethos? Explain.

Is Newstok’s argument primarily deductive or inductive? Why do you think that he chose this structure?