THE BENEFITS OF COOPERATION

Do nice guys always finish last? If they do—if a person who sacrifices for the common good always does worse than a person who acts selfishly—then cooperative behavior should not exist. But recent studies suggest that humans have a strong innate tendency toward cooperation. How could such behavior evolve?

Cooperative behavior will evolve only if cooperation reaps greater benefits than selfishness. To see how this might occur, imagine a hypothetical situation. You own a fishing boat and make your living by harvesting rockfish off the coast of Oregon. This is a profitable business as long as the total number of fishing boats is not so large that the rockfish population declines. Too much fishing will damage and ultimately destroy the common resource shared by all the fishing boats (see Concept 42.6).

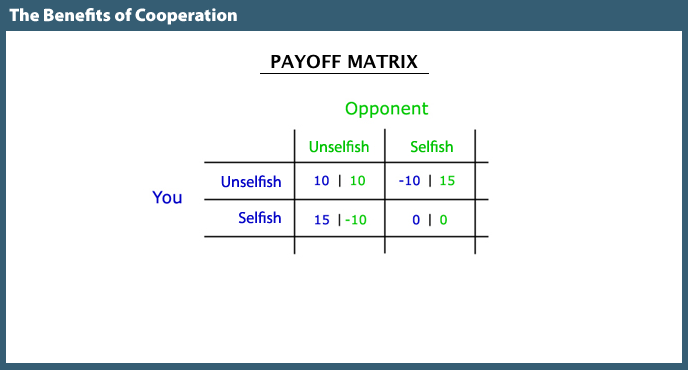

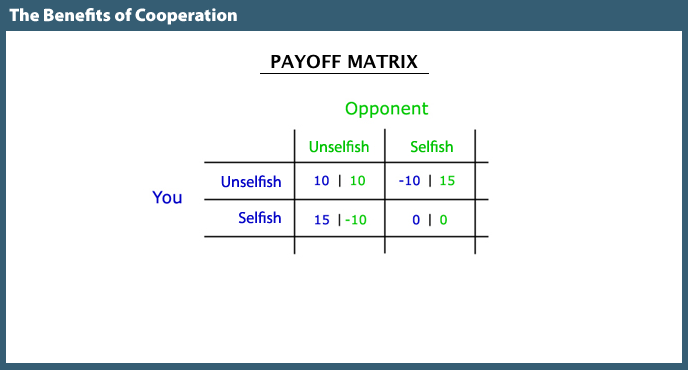

If you are selfish, and add another boat to your fleet, you could catch more fish and enjoy a short-term economic gain. If you are unselfish, but another person adds a boat, you will suffer an economic loss because there are fewer fish for you to catch. It would appear that the only rational strategy is to be selfish. You can explore whether this is so by trying out selfish and unselfish behaviors in a “game” against another person who acts only to maximize their own short-term economic gain (actually you are playing against a computer, of course, and not another person). If you are unselfish while the other person adds one more fishing boat, you lose 10 points whereas they gain 15 points. If you and the other person both decide to be selfish neither of you gain anything. Finally, if you both are unselfish, and neither of you adds a boat, you both gain a “payoff” of 10 points. (These “points” represent your economic gain—the object is not to “beat” the other person but to maximize your gain).

Let's start by assuming that the other person is always a total stranger who knows nothing about you, and cannot predict how you will behave. To see what happens, check the box that says “New Person each time.” First, try ten games in which you are unselfish and don't add another fishing boat by clicking the Unselfish button 10 times. Notice that the other person always plays selfishly.

Textbook Reference: Concept 45.6 Ecological Challenges Can Be Addressed through Science and International Cooperation

Question 1 What score did you receive?

Now try ten games in which you are selfish, by clicking the Selfish button ten times.

Question 2 What score did you receive?

Question 3 Based on your answers to Questions 1 and 2, is it best to be selfish or unselfish?

Of course, the problem in the real world is that if everybody is selfish, the rockfish will be decimated, and all the people who depend on fishing for a livelihood will lose that livelihood. When you played Selfish ten times, you did better than when you played Unselfish, but what was your final payoff? This is what is called the Tragedy of the Commons—a true tragedy in the original sense used by the ancient Greeks to mean an outcome that is unavoidable. In a famous paper published in 1968, the ecologist Garrett Hardin pointed out that humans depend on many shared resources, so that this tragedy can touch us all.

Is Hardin's Tragedy of the Commons really unavoidable? No, it can be avoided through cooperation. Recall that if you and the other person were to cooperate, each of you would gain 10 points and the rockfish fishery would be sustainable. But how can you achieve the necessary cooperation?

To see one possibility, play the game again, but this time check the box “Same person each time” to indicate that the other person that you are interacting with is the same person throughout. As before, first, try ten bouts of playing Unselfish.

Question 4 What score did you receive?

Now play ten bouts of playing Selfish.

Question 5 What score did you receive?

Question 6 Based on your answers, is it best to be selfish or unselfish?

Why did the outcome change? The difference lies in the fact that the other person cooperated with you when you began by being unselfish. Because you were interacting with the same person throughout, there was a chance for that person to learn about your behavior, and to change his or her behavior in response. Playing the game against a different person each time, as you did at first, represents a situation in which no such knowledge could be gained.

In conclusion, cooperation among individuals is more likely when they interact repeatedly and can establish reputations for good behavior. Even when interactions occur within groups and the exact same individuals do not interact repeatedly, cooperation can occur if reputations become established within the group—as is highly likely in human groups. Furthermore, new research indicates that cooperation is strengthened in groups that have a mechanism for “policing”—for excluding selfish “cheaters” from cooperative actions and the benefits that go with them.

Suggested Reading

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 162:1243–1248.

Maynard Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK.

Nowak, M. A. and K. Sigmund (2005). Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature 437:1291–1298.