10.1 10 Southeast Asia

10.1.1 Geographic Insights: Southeast Asia

Geographic Insights: Southeast Asia

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Climate Change, Food, and Water: Conversion of forests to oil palm plantations, rice farms, subsistence plots, and settlements all add to greenhouse gas emissions, which intensify climate change and leave many people vulnerable to both flooding and occasional droughts.

2. Globalization and Development: Globalization has brought spectacular economic successes and occasional, dramatic economic declines. Urban incomes soar during periods of growth, but the poor are vulnerable during periods of global economic decline.

3. Power and Politics: Militarism, corruption, and favoritism are recurring issues in Southeast Asia. Although modernization and prosperity have brought significant increases in democratic participation, there have also been reversals, especially during periods of economic downturn. These sometimes result in violence, often against ethnic minorities.

4. Population and Gender: Economic change has brought better job opportunities and increased status for women, who are then choosing to have fewer children. The improving role and status of women has increased awareness that sex trafficking is an abuse of human rights.

5. Urbanization, Food, and Development: The development of export-oriented modernized agriculture and agribusiness have forced farmers who were once able to produce enough food for their families to migrate to cities, where jobs that fit their skills are scarce, where they must purchase their food, and where the only affordable housing is in slums that lack essential services. Surplus skilled and semiskilled workers, especially women, often migrate abroad for employment.

The Southeast Asian Region

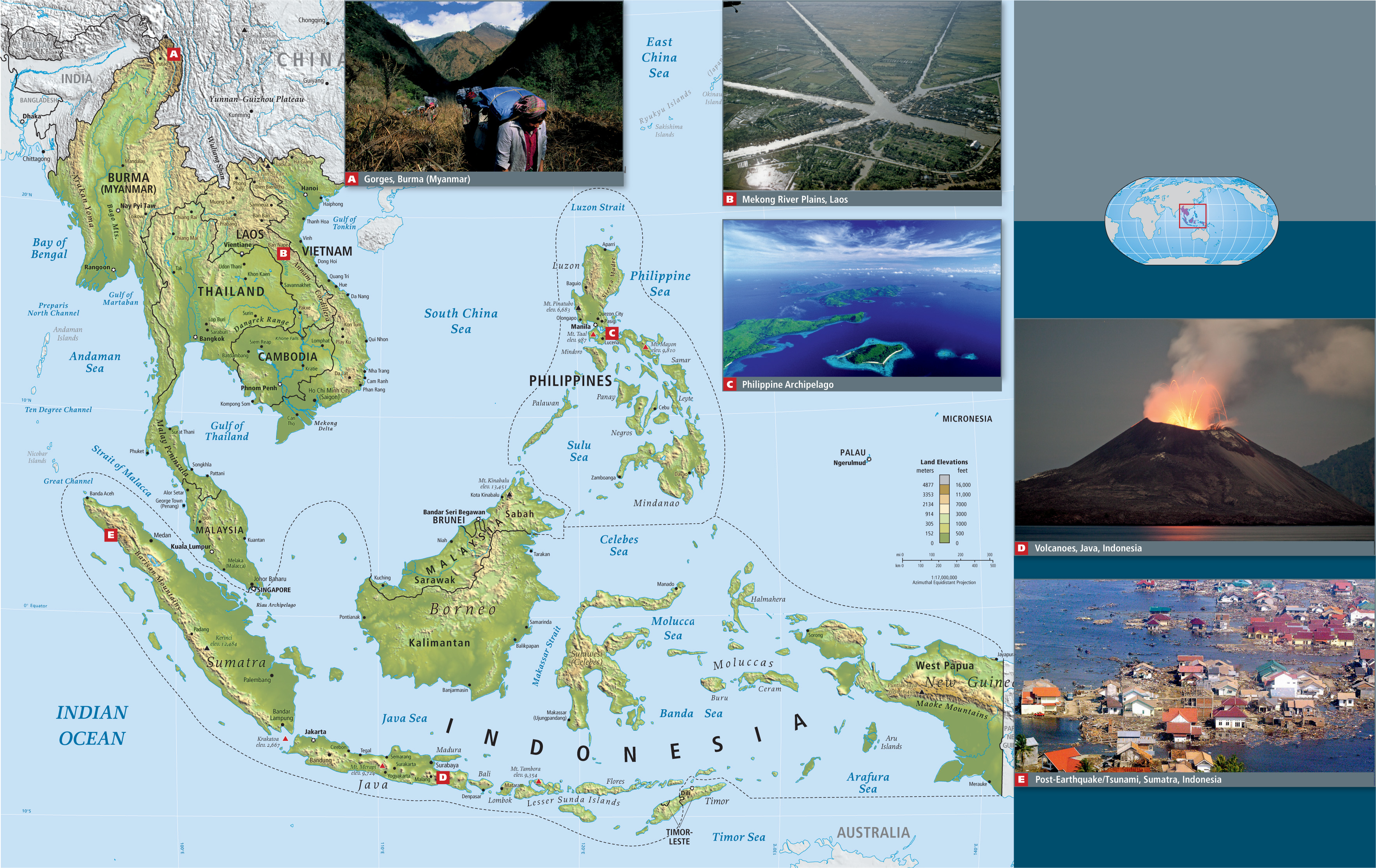

The region of Southeast Asia (see Figure 10.1) has attracted global attention for several decades because so many of its countries had emerged poverty-stricken from World War II only to embark on a rapid journey to relative prosperity. There have been ups and downs: difficulties in finding smooth paths to stable democratic processes and institutions; urbanization at too rapid a pace; and a tendency to rely on development strategies that carry grave environmental and social side effects. Still, the region has modeled many ideas now emulated by other developing regions: rapid industrialization, expansion of the middle class, education for the masses, empowerment for women, improvement of food security, public health care, and slower population growth.

The nine thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights above. Vignettes, like the one that follows about the rights of a group of people indigenous to the state of Sarawak on the island of Borneo, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

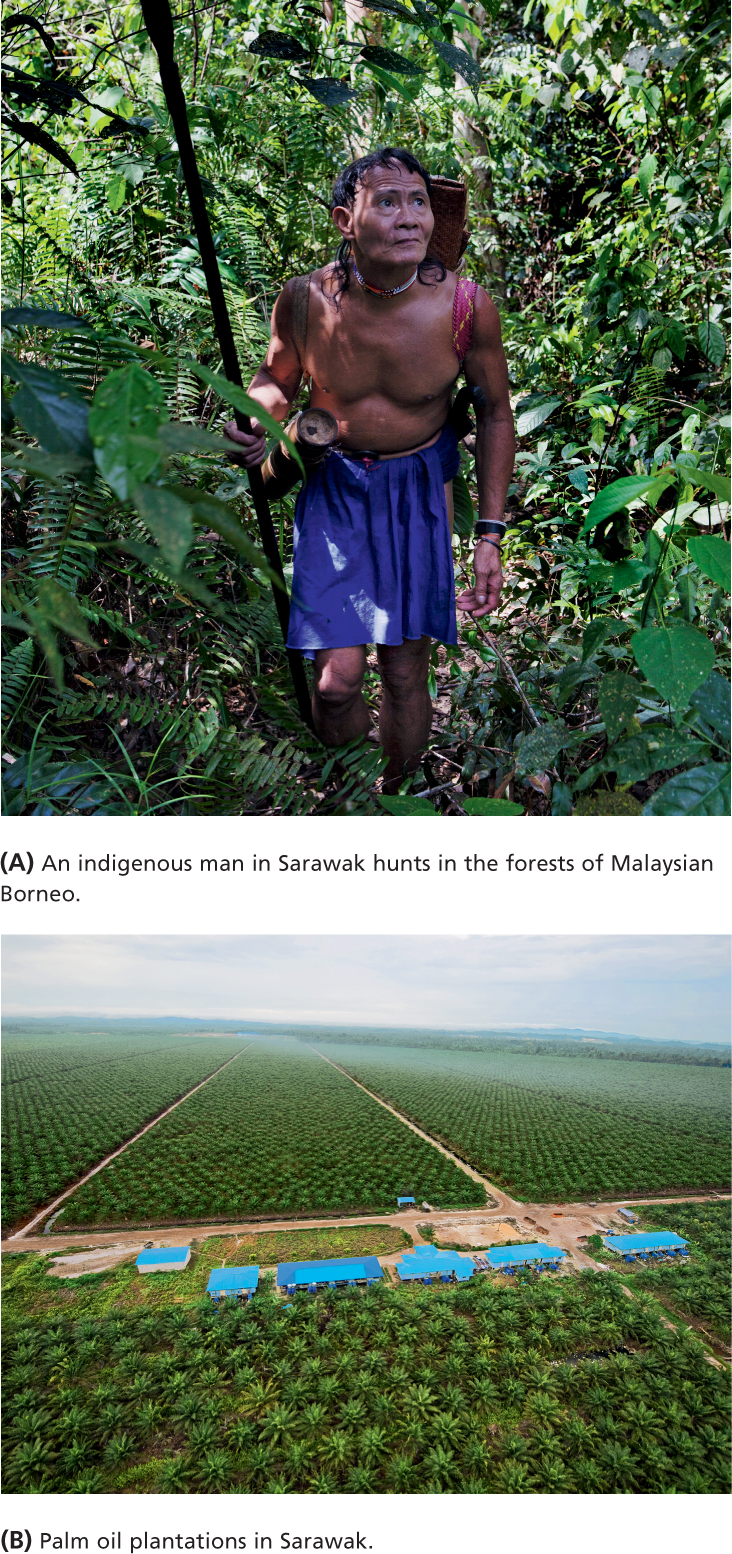

In December 2005, a group of indigenous people in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, on the island of Borneo (see the Figure 10.1 map), attended a public meeting wearing orangutan masks. They carried signs informing onlookers that, although the government protects natural areas for orangutan, it ignores the basic right of indigenous people to live on their own ancestral lands and practice their forest skills (Figure 10.2A).

Over the years, Sarawak forest dwellers have tried many tactics to save their lands from deforestation by logging companies preparing to expand oil palm plantations (see Figure 10.2B). Palm oil is a major food and cosmetic export; it is sold primarily to Europe, North America, Japan, and China. In the mid-twentieth century, the Sarawak state government began licensing logging companies to cut down tropical forests occupied by indigenous peoples (Figure 10.3) and export the timber. By the 1980s, 90 percent of Sarawak’s lowland forests had been degraded and 30 percent had been clearcut, with much of the cleared area replaced by oil palm plantations. As a consequence, indigenous people found that even on uncleared land, their hunts declined. Meanwhile, streams and rivers became polluted with eroded sediment and by fertilizers and pesticides applied to the palm trees. However, virtually none of the profits from palm oil were returned to the communities affected by the conversion of forests to plantations.

In the 1990s, a group of citizens in Berkeley, California, who were concerned about news reports of the deforestation in Sarawak, organized the Borneo Project. They offered to become a “sister city” to one indigenous group in Sarawak, the Uma Bawang, giving help wherever it was needed. With the help of the Borneo Project, the Uma Bawang began a community-based mapping project in 1995. Using rudimentary compass-and-tape techniques, they began mapping both the extent and the biological content of their forest home. Since then, indigenous people from across Sarawak have learned how to use global positioning systems (GPS), geographic information systems (GIS), and satellite imagery to make more sophisticated maps. The power of these maps was demonstrated in 2001, when they helped win a precedent-setting court case that protected indigenous lands from encroachment by oil palm plantation.

This favorable court ruling was challenged in 2005, when the government appealed, but in 2009, the Malaysian federal court ruled in favor of the Uma Bawang. The decision stated that native customary land rights had been protected since 1939, when British colonial officials had directed the district lands and survey departments to map the boundaries of native lands. Now indigenous people have the right to sue the government for past illegal leases to logging companies; as of 2011, some 203 such cases were in litigation. The outcome of this litigation is as yet unclear; in the Indonesian part of Borneo, deforestation for oil palm plantations is proceeding rapidly, as shown in the 2011 video, “Indigenous Community Witnesses End of Forest for Palm Oil,” at http://tinyurl.com/d5pmr49. [Source: The Borneo Wire. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

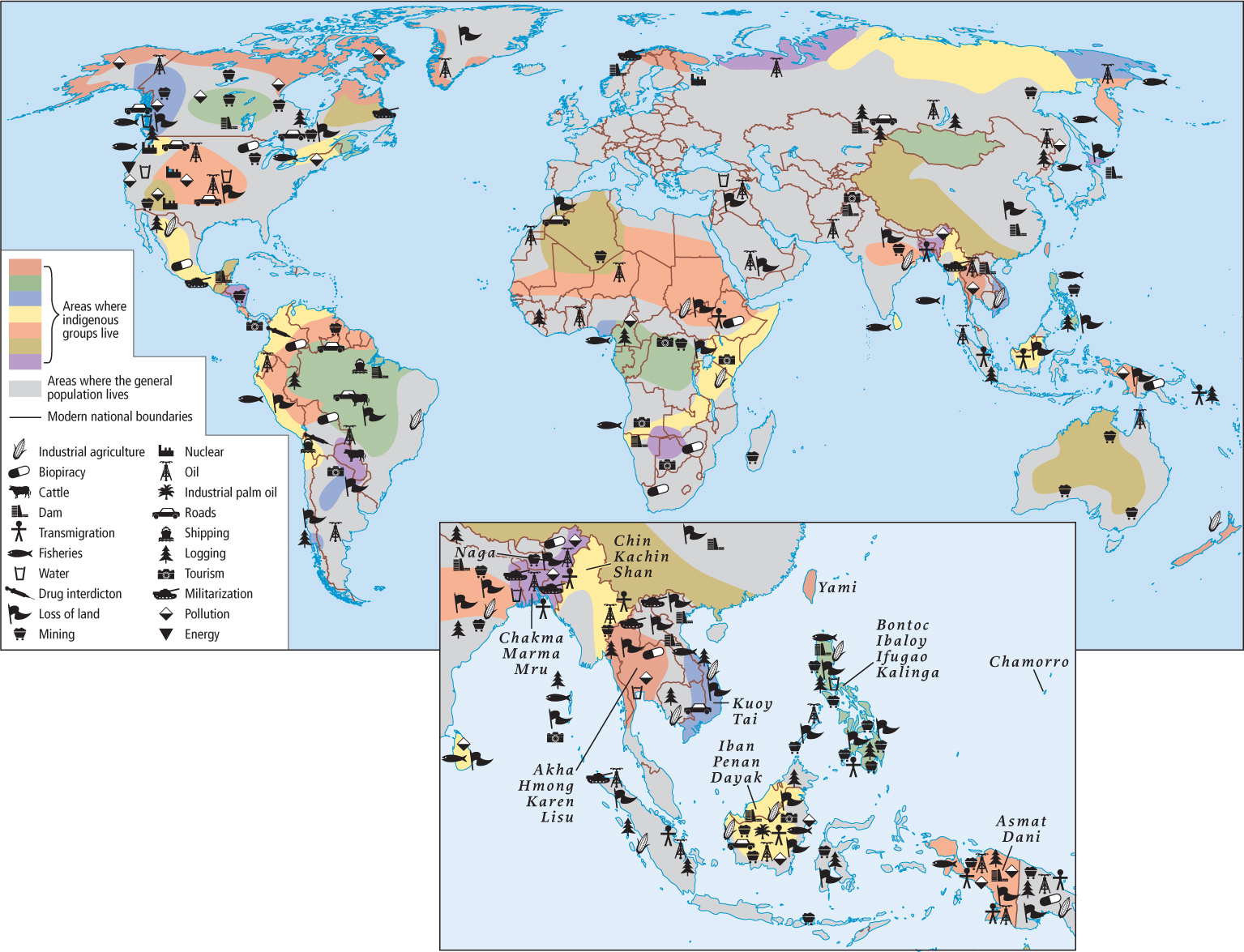

This account of the tactics that indigenous groups are using to secure their rights to control and manage their ancestral lands complements the documentation of similar struggles in Middle and South America and highlights a number of themes in this book: globalization, power and politics, development, and access to food and water. As the interplay of these themes becomes better understood, issues that previously seemed to have only local significance are shown to be international or even global in nature. This connection of the local to the global presents both challenges and opportunities for the world’s indigenous people (see Figure 10.3). On the one hand, the global market provides the demand for timber and palm oil; on the other, it is support from the global arena that enables efforts like the Borneo Project to help communities like that of the Uma Bawang to have their land claims validated. In fact, mapping as a tactic for helping indigenous groups secure their legal rights to ancestral lands has now become a global phenomenon. Hundreds of indigenous groups throughout the world are collaborating with mapping specialists, many of them geographers, often with the result that their land rights are for the first time formally recognized by governments. In 2007, the United Nations passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People; in 2010, President Obama signed the declaration for the United States, which previously had voted against it. The United Nations’ State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples report documents several of these efforts. It is available online at http://tinyurl.com/ybpfgpp.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Indigenous land claims are no longer just local issues. Indigenous groups have shifted their efforts to secure their rights to ancestral lands to the global scale, highlighting a trend in which many issues that were once local or national are now becoming global concerns.

Indigenous land claims are no longer just local issues. Indigenous groups have shifted their efforts to secure their rights to ancestral lands to the global scale, highlighting a trend in which many issues that were once local or national are now becoming global concerns.