Mainland Southeast Asia: Burma and Thailand

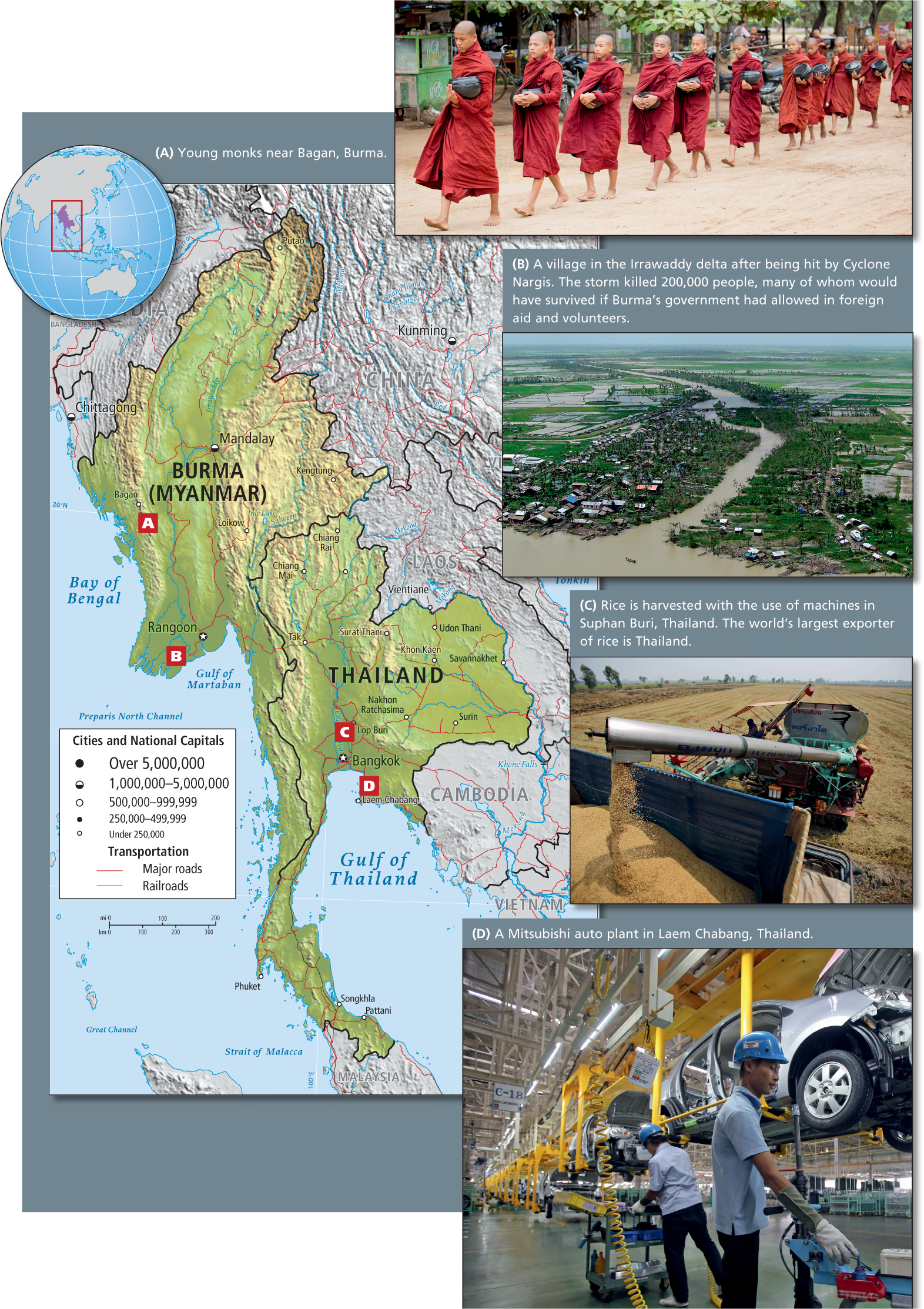

Burma and Thailand occupy the major portion of the Southeast Asian mainland and share the long, slender peninsula that reaches south to Malaysia and Singapore (Figure 10.29 map). Although Burma and Thailand are adjacent and share similar physical environments, Burma is poor, depends on agriculture, and is just beginning to show signs of emerging from a repressive military government, whereas Thailand is rapidly industrializing and has had a more open, less repressive society, despite occasional coups d’état and military rule (the last in 2006). Both countries trade in the global economy, but in different ways: Burma supplies raw materials (including illegal drug components), while Thailand, though the world’s largest exporter of rice (see Figure 10.29C), earns most of its income by providing low- to medium-wage labor, by hosting many multinational manufacturing firms, and through its thriving tourism industry that has a worldwide clientele.

The landforms of Burma and northeastern Thailand consist of a series of ridges and gorges that bend out of the Plateau of Tibet and descend to the southeast, spreading across the Indochina peninsula. The Irrawaddy and Salween rivers originate far to the north on the Plateau of Tibet and flow south through narrow valleys. The Irrawaddy forms a huge delta at the southern tip of Burma (see Figure 10.29B). The Chao Phraya flows from Thailand’s northern mountains through the large plain in central Thailand and enters the sea south of Bangkok. Most farming is done in the Burmese interior lowlands around Mandalay and in Thailand’s central plain.

Ancient migrants from southern China, Tibet, and eastern India settled in the mountainous northern reaches of Burma and Thailand. The rugged topography has in the past protected these indigenous peoples from outside influences. The largest of these groups are the Shan, Karen, Mon, Chin, and Kachin, many of whom still follow traditional ways of life and practice animism. By contrast, the southern Burmese valleys and lowlands and Thailand’s central plain are Buddhist, modernized, and have much urban development (Figure 10.29A). Burma is named for the Burmans, who constitute about 70 percent of the population and live primarily in the lowlands. Thailand is named for the Thais, a diverse group of indigenous people who originated in southern China. Both countries are predominantly Buddhist.

Burma

Burma is rich in natural resources. Between 70 and 80 percent of the world’s remaining teakwood still grows in its interior uplands; a single tree can be worth U.S.$200,000. Other resources include oil, natural gas (of particular interest to India, China, and the United States), tin, antimony, zinc, copper, tungsten, limestone, marble, and gemstones. However, in part because of corruption and repression by a military junta, Burma ranks as one of the region’s poorest countries, with an estimated per capita annual GNI of U.S.$1535 (2011) and an HDI rank of 149. About 70 percent of the people still live in rural villages; their livelihoods are based primarily on wet rice cultivation and the growing of corn, oilseeds, sugarcane, and legumes, and on logging teak and other tropical hardwoods. People in rural areas travel to nearby markets to sell or trade their produce for necessities (Figure 10.30).

Burma is estimated to supply opium for over 60 percent of the heroin market in the United States; it alternates with Afghanistan as the world’s largest producer. Opium poppy cultivation, along with methamphetamine production, is the major source of income for a number of indigenous ethnic groups. The Wa, for example, who number about 700,000, depend on illegal drug production for 90 percent of their income and are said to protect their territory in northern Burma with surface-to-air missiles. The military government of Burma has encouraged, manipulated, and profited from the drug traffic, especially in the lightly settled uplands and mountains near the Thai border. When indigenous inhabitants protested, they were silenced by assassinations, plundering, resettlement, and the abduction and sale of their young women into the sex industries in neighboring countries. This repression resulted in hundreds of thousands of Burmese people becoming refugees; many now live in camps in Thailand and Bangladesh. The 730,000 mostly Muslim migrants from Bangladesh taking refuge in Burma have suffered violence from the Burmese. Since 1997, the international community has applied economic sanctions on trade and investments against Burma’s military government, but until recently these efforts had little or no effect.

Unlike pro-democracy movements that resulted in real change elsewhere in the region, for more than two decades, people in Burma have protested futilely the rule of a corrupt and authoritarian military regime. In 1990 when, in a landslide, the people elected Aung San Suu Kyi to lead a civilian reformist government, the regime refused to step aside. Suu Kyi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, spent 15 years under house arrest between 1989 and 2010. Widespread pro-democracy protests were repeatedly and brutally repressed after 1990. Elections in 2010, still overwhelmingly controlled by the military, brought a modestly reformist former general, Thein Sein, to the presidency. Limited free elections in 2012 gave the pro-democracy party a landslide victory, with Aung San Suu Kyi winning a seat in parliament. Her party won 43 out of the 45 seats up for election that year. There are, however, 665 parliamentary seats overall, most still controlled by the military. In 2012, Suu Kyi belatedly claimed her Nobel Prize in Norway and visited the United States. Early indications are that President Thein Sein is serious about change, a sentiment that he communicated to President Barack Obama during Obama’s visit to Burma in November 2012.

234. NEW TECHNOLOGY BEAMS BURMA PROTESTS ACROSS GLOBE

234. NEW TECHNOLOGY BEAMS BURMA PROTESTS ACROSS GLOBE

235. FORMER U.S PRESIDENT, JIMMY CARTER, CALLS FOR MORE INTERNATIONAL PRESSURE ON BURMA

235. FORMER U.S PRESIDENT, JIMMY CARTER, CALLS FOR MORE INTERNATIONAL PRESSURE ON BURMA

Thailand

During the boom years of the mid-1990s, Thailand was known as one of the Asian “tiger” economies, meaning that it was rapidly approaching widespread modernization and prosperity. Thailand takes pride in having avoided colonization by European nations and in having transformed itself from a traditional agricultural society into a modern nation. According to the United Nations, between 1975 and 1998, Thailand had the world’s fastest-growing economy, averaging an annual growth in GNI per capita of 4.9 percent (U.S. annual growth then averaged 1.9 percent). At the same time, the country kept unemployment relatively low for a developing country—at 6 percent—and inflation in check at 5 percent or lower. The soaring economic growth resulted from the rapid industrialization that took place in Thailand when the government provided attractive conditions for large multinational corporations. They had situated themselves in Thailand to take advantage of its literate yet low-wage workforce, its lenient laws about environmental degradation, and its permissive regulation of manufacturing and trade.

Urbanization and Industrialization

The Bangkok metropolitan area, which lies at the north end of the Gulf of Thailand, contributes 50 percent of the country’s wealth and contains 16 percent (10.5 million people) of its population (see the Figure 10.23 map). Cities elsewhere in Thailand are also growing and attracting investment, especially Chiang Mai in the north, Khon Kaen in the east, Surat Thani on the Malay Peninsula, and Laem Chabang (see Figure 10.29D).

Despite its urbanizing trends, about 41 percent of Thai working people are still farmers, but, according to official statistics, they produce less than 13 percent of the nation’s wealth. (Remember, though, that much of what farmers, especially women, produce is not counted in the statistics.) Just 31 percent of the population, or about 24 million people, live in cities, many in crowded, polluted, and often impoverished conditions. It is common for thousands of immigrants from the countryside to live in slums along urban riverbanks, as in Indonesia (see Figure 10.23A). Industrialization has had unanticipated detrimental side effects in Thailand. Many of the millions of rural people drawn to the cities seeking jobs, status, and an improved quality of life arrive only to find a difficult existence and meager earnings.

Political Stability

Thailand, which is actually a monarchy where the much-revered king usually plays a low-profile role, had a reputation as a rapidly developing democracy that allowed for protest and provided mechanisms for constitutional adjustments and smooth transitions after regular elections. Nevertheless, in 2006, Thailand’s democracy was weakened when a military coup d’état, professing loyalty to the king, overthrew an apparently corrupt but popular prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra. Red-shirted crowds of Thaksin supporters faced off against yellow-shirted supporters of the monarchy and military. Cycles of bloody street battles and arrests ensued well into 2012. Mr. Thaksin, still highly controversial because of corruption charges and a tendency to manipulate his red-shirt supporters, now lives in exile, but is angling to return. The present prime minister is his younger sister, Yingluck Shinawatra. She is pursuing a program of national reconciliation, strongly opposed by those who do not want the perpetrators of civil violence to be exonerated. The blows to democracy are likely to affect economic development because the civil unrest discourages tourism and investment.

While Thailand’s infrastructure is not as developed as those of other middle-income countries, hopes are high: the emerging Asian Highway network (see the Figure 10.16 map) should facilitate trade with India and China; Thailand now has three international airports, making it easier for tourists to visit; and more than one-third of the population, or 23 million people, have cell phones, which elsewhere have helped facilitate entrepreneurship and general development.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Burma and Thailand differ significantly in political structure, economy, and sociocultural variables.

Burma and Thailand differ significantly in political structure, economy, and sociocultural variables. Although rich in natural resources, Burma is one of the region’s poorest countries.

Although rich in natural resources, Burma is one of the region’s poorest countries. Thailand had been regarded as a successful democracy on the fast track to development, but a recent coup d’état and civil unrest have slowed economic growth and cast a cloud over its future.

Thailand had been regarded as a successful democracy on the fast track to development, but a recent coup d’état and civil unrest have slowed economic growth and cast a cloud over its future.