Island and Peninsular Southeast Asia: Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei

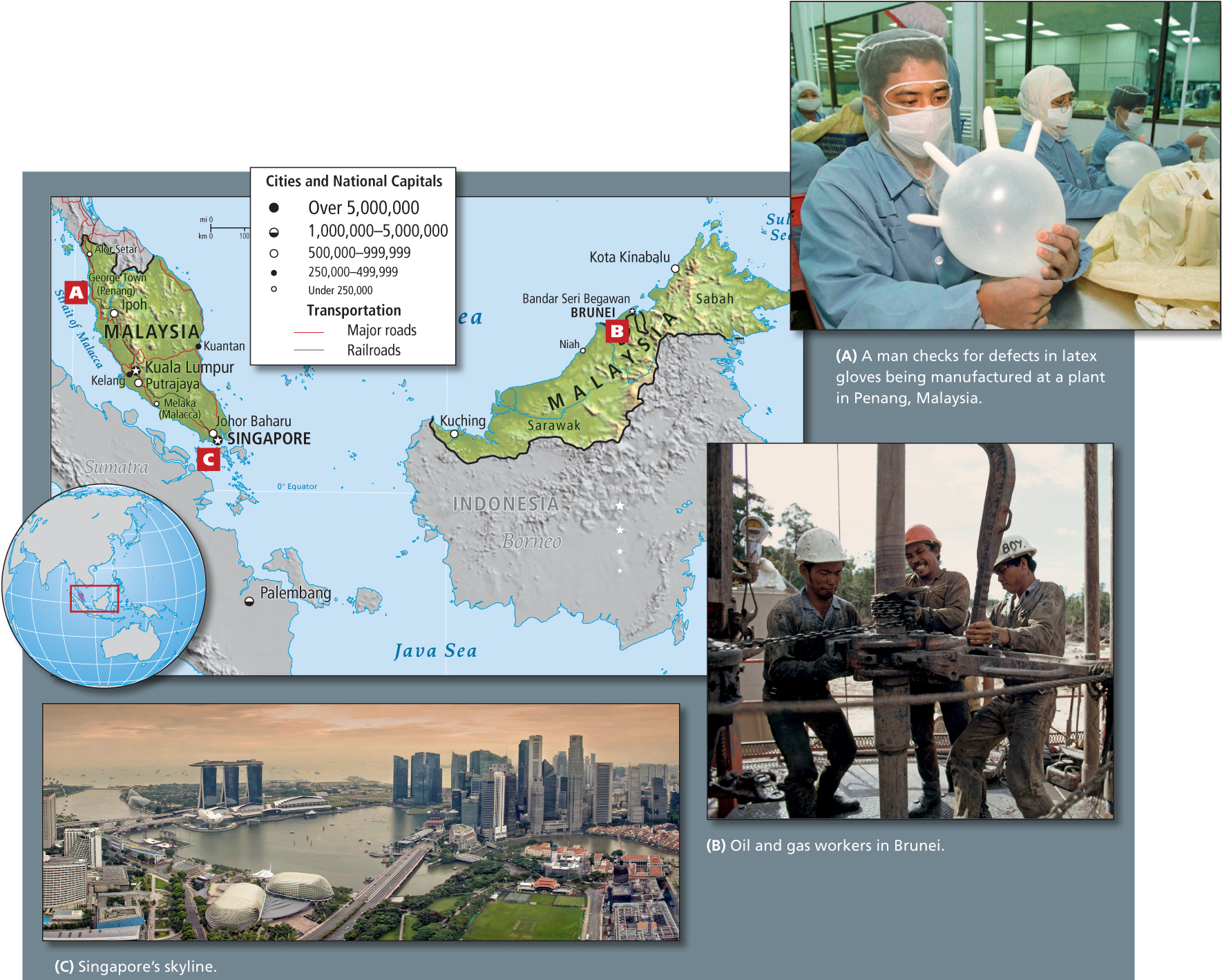

Malaysia and neighboring Singapore and Brunei are the most economically successful countries in Southeast Asia. Malaysia was created in 1963 when the previously independent Federation of Malaya (the southern portion of the Malay Peninsula) was combined with Singapore (at the peninsula’s southernmost tip) and the territories of Sarawak and Sabah (on the northern coast of the large island of Borneo to the east) (Figure 10.32 map). All had been British colonies since the nineteenth century. Singapore became independent from Malaysia in 1965. The tiny and wealthy sultanate of Brunei, also on the northern coast of Borneo, refused to join Malaysia and remained a British colony until its independence in 1984. Singapore and Brunei are two of the wealthiest countries in the world, both with annual per capita incomes of close to $50,000 (PPP). Virtually all citizens have a high standard of living, with Brunei’s wealth coming from its oil and natural gas and Singapore’s from a diversified economy grounded in global trade. Malaysia also has a diversified economy, and though it is much less wealthy than these two neighbors, with an annual GNI per capita (PPP) of about $14,000 (see Figure 10.22A).

Malaysia

Malaysia is home to 28.9 million ethnically diverse people. Slightly over 50 percent of Malaysia’s people are Malays, and nearly all Malays are Muslims. Ethnic Chinese, most of whom are Buddhist, make up nearly 24 percent of the population. Just over 7 percent of people in Malaysia are Tamil- and English-speaking Indian Hindus, and 11 percent are indigenous peoples of Austronesian ancestry, who live primarily in Sarawak and Sabah. Until the 1970s, conflicts among these many groups divided the country socially and economically. Malaysians have worked hard to improve relationships among their diverse cultural groups, and they have had noteworthy success.

Today, most Malaysians (86 percent) live on the Malay Peninsula, which has 40 percent of the country’s land area. Throughout most of its history, indigenous Malays and a small percentage of Tamil-speaking Indians inhabited peninsular Malaysia. The Indians were traders who plied the Strait of Malacca, the ancient route from India to the South China Sea. Even before the eastward spread of Islam in the thirteenth century, Arab traders began using the straits in the ninth and tenth centuries, stopping at small fishing villages along the way to replenish their ships. By 1400, virtually all of the ethnic Malay inhabitants of peninsular Malaysia had converted to Islam.

During the colonial era, the British brought in Chinese Buddhists and Indians to work as laborers on peninsular Malaysian plantations. These Overseas Chinese eventually became merchants and financiers, while Indians achieved success in the professions and in small businesses. The far more numerous Malays remained poor village farmers and plantation laborers. As economic disparities widened, antagonism between the groups increased. After independence, animosities exploded into widespread rioting by the poor in 1969. Political rights were suspended, and it took 2 years for the situation to calm down. The violence so shocked and frightened Malaysians that they agreed to address some of the fundamental social and economic causes.

After a decade of discussions among all groups, Malaysia launched a long-term affirmative action program, called Bumiputra, in the early 1980s, designed to help the Malays and indigenous peoples advance economically. The policy required Chinese business owners to have Malay partners. It set quotas that increased Malay access to schools and universities and to government jobs. As the program evolved in the 1980s, the goal became to bring Malaysia to the status of a fully developed nation by the year 2020. The program has succeeded in narrowing some social inequalities fairly rapidly. In 2011, the United Nations ranked Malaysia 61st, in the high (but not highest) development category. As incomes in Malaysia have increased, wealth disparity (the gap between rich and poor) has narrowed rather than widened. This is an unusual pattern.

The economy of Malaysia has traditionally relied on raw materials export products such as palm oil, rubber, tin, and iron ore (see Figure 10.32A). In contrast, much of the growth of the 1990s came from Japanese and U.S. investment in manufacturing, especially of electronics, and from offshore oil production in the South China Sea. Timber exports are also important (especially in Sarawak and Sabah). The development of oil palm and rubber tree plantations on cleared forest land (see the vignette at the start of the chapter) has brought global criticism because of its multiple negative impacts: deforestation, burning of scrap vegetation, greenhouse gas emissions, river pollution, the demise of forest species (such as the orangutan, which in Malay means man of the forest), and the displacement of indigenous people. Because many countries in this region are responsible for similar problems, Malaysia called for reinforcement of the 2002 ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution.

The Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur, boasts beautifully designed skyscrapers like those in Singapore, including what were in 2000 the two tallest buildings in the world—Petronas Towers I and II (buildings elsewhere have since surpassed the towers in height). Nonetheless, at least one-fifth of the city’s residents are squatters, some on land in the shadows of the towers, some on raft houses on rivers or bays. Now Malaysia is hoping to benefit from a new, multibillion-dollar high-tech manufacturing corridor just south of Kuala Lumpur. Called the MSC Malaysia, it includes two new cities: the new federal administrative center, called Putrajaya, and another city named Cyberjaya. The MSC was expected to help the nation spring fully prepared into a prosperous twenty-first century, but growth has been undercut by various global recessions.

Like many on the Asian development fast track, Malaysia has volatile economic patterns. Currency values and stock market prices may fluctuate widely. Lavish building projects may be halted for years, as they were in Kuala Lumpur from 1998 through 2001 and again during the recession that began in 2007. Overall, however, it does seem that Malaysia is likely to have an increase in prosperity and to continue to foster cultural diversity while discouraging extremist factions, religious or ethnic.

Singapore

Singapore occupies one large and many small hot, humid, flat islands just off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. Its 5.1 million inhabitants, all of them urban, live at a density of over 12,224 people per square mile (7640 per square kilometer), yet as one of the wealthiest countries in the world, Singapore’s urban landscapes are elegant (see Figure 10.32C; see also Figure 10.23B). Singapore’s wealth is based on pharmaceutical, biomedical, and electronic manufacturing; financial services; oil refining and petrochemical manufacturing; and oceanic transshipment services. Unemployment is low and poverty unusual, except among temporary and often undocumented immigrants—primarily from Indonesia—who live on little islands surrounding Singapore. Singaporeans seem to share the notion that financial prosperity is a worthy first priority, but although the free market economy reigns, the government has a strong regulating role.

Ethnically, Singapore is overwhelmingly Chinese (76.7 percent). Malays account for 14 percent of the population, Indians for 7.9 percent, and mixed or “other” peoples for 1.4 percent. Singapore’s people are diverse in religious beliefs: 42 percent are Buddhist or Taoist, 18 percent are Christian, 16 percent are Muslim, and 5 percent are Hindu; the rest include Sikhs, Jews, and Zoroastrians. As in Malaysia and Indonesia, the Singapore government officially subscribes to a national ethic not unlike Pancasila in Indonesia. The nation commands ultimate allegiance; loyalty is to be given next to the community and then to the family, which is recognized as the basic unit of society. Individual rights are respected but not championed. The emphasis is on shared values, racial and religious harmony, and community consensus rather than majority rule, which is thought to lead to conflict.

Singapore has a meticulously planned cityscape with safe, clean streets and little congestion because of an elaborate light rail system. Eighty percent of the people live in government-built housing estates (see Figure 10.23B), and workers are required to contribute up to 25 percent of their wages to a governmentrun pension fund. However, enforced by law, home care of the elderly is the responsibility of the family. Each child, on average, receives 10 years of education and can continue further if his or her grades and exam scores are high enough. Literacy is close to 95 percent. The government strictly controls virtually all aspects of society. Permits are required for almost any activity that could have a public effect: having a car radio, owning a copier, working as a journalist, having a satellite dish, being a sex worker, or performing as a street artisan or entertainer. Law and order are strictly enforced. Some years ago, a visiting U.S. teenager was sentenced to a caning for spray-painting graffiti. Drug users are severely punished, and drug dealers are sentenced to life imprisonment or death. But virtually all citizens of Singapore seem to have accepted this control and strictness in return for a safe city and the fourth-highest GNI per capita in the world.

Brunei

Brunei is a country, a little smaller than Delaware, on the north coast of Borneo, where it is situated between the Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah. It is a sultanate that has been ruled by the same family for more than 600 years. The sultan is both the head of government and the head of state, and the country became independent in 1984. Brunei has a small economy, with over half of its GNI from crude oil and natural gas production that make up 90 percent of the country’s exports (see Figure 10.32B). Significant income from overseas investments, primarily in the petrochemical industries, helps to give Brunei the world’s eighth-highest per capita GNI income ($45,753 in 2011). Medical care is free, as is education through the university level. Ethnically, Malays comprise two-thirds of the population, Chinese people about 11 percent, and a variety of others make up the rest. Sixty-seven percent of the people are Muslim, 13 percent are Buddhist, 10 percent Christian, and 10 percent practice other beliefs. More than 90 percent of the population is literate and the life expectancy is over 75 years.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Singapore and Brunei are very small, relatively stable, and very wealthy countries.

Singapore and Brunei are very small, relatively stable, and very wealthy countries. The largest and most populous country, Malaysia, which has an increasingly diversified economy, has managed to control ethnic and political strife through the positive efforts on the part of the citizenry to painstakingly accommodate all interests.

The largest and most populous country, Malaysia, which has an increasingly diversified economy, has managed to control ethnic and political strife through the positive efforts on the part of the citizenry to painstakingly accommodate all interests. Malaysia is making some efforts to cope with its environmental issues caused mostly by unregulated development.

Malaysia is making some efforts to cope with its environmental issues caused mostly by unregulated development.