Human Patterns over Time

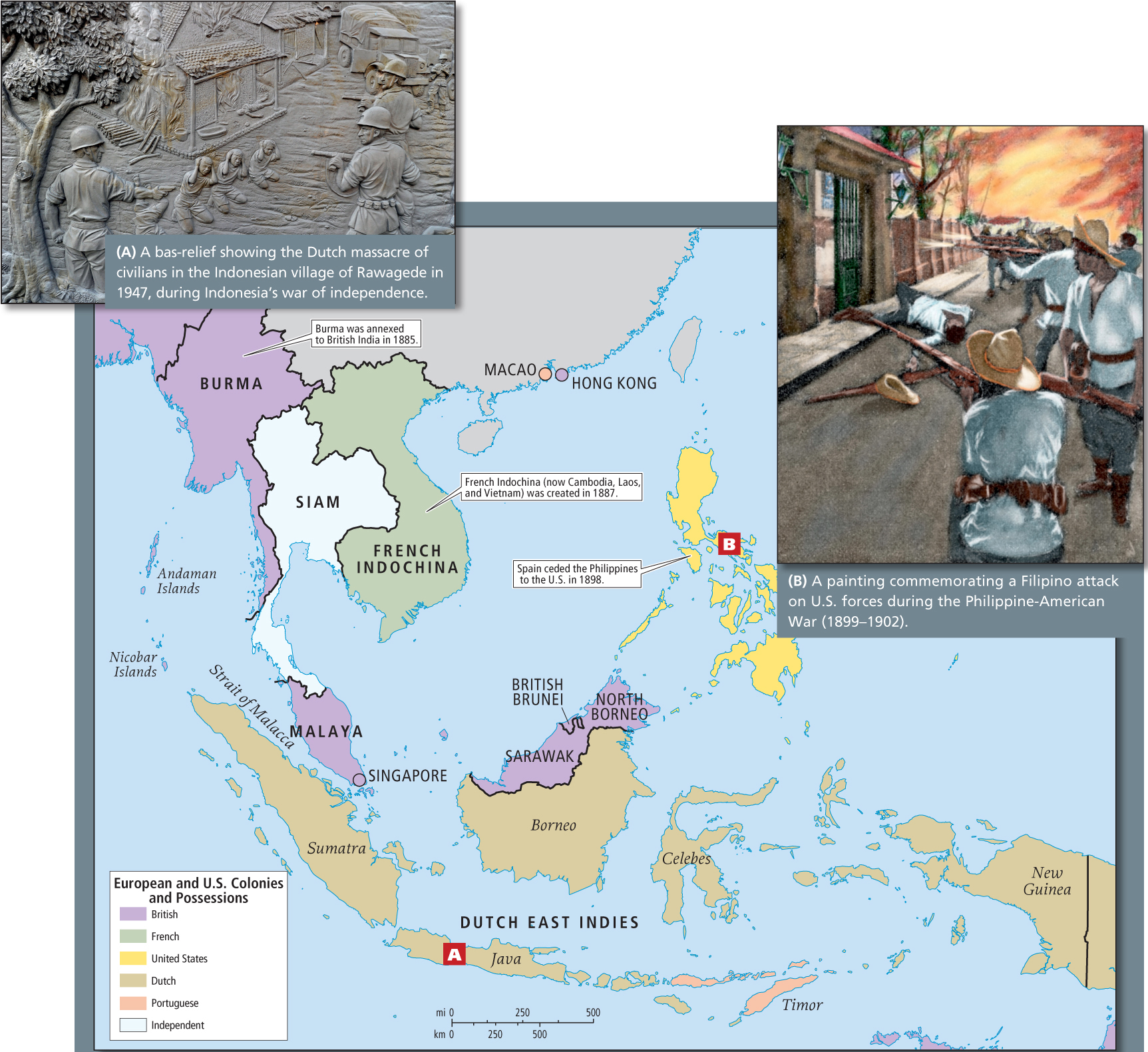

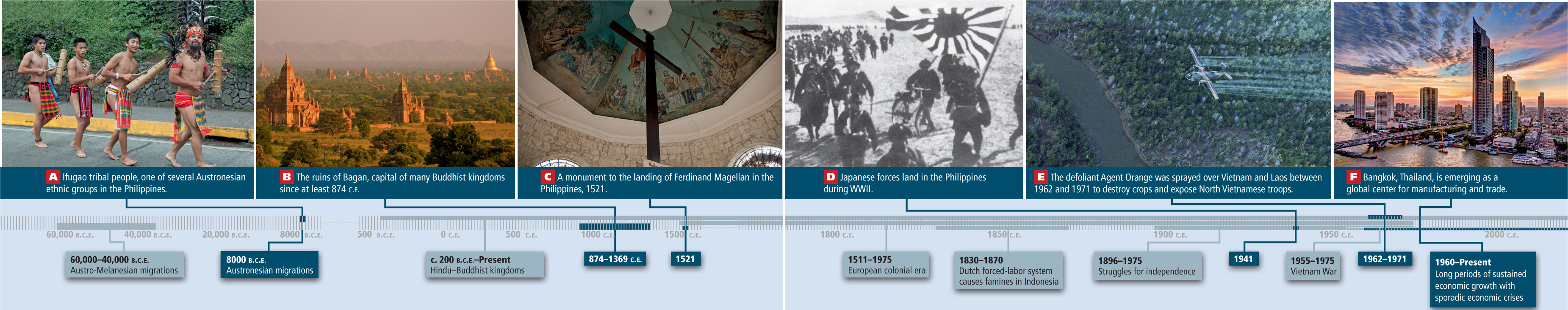

First settled in prehistory by migrants from the Eurasian continent, Southeast Asia was later influenced by Chinese, Indian, and Arab traders. Later still, it was colonized by Europe (from the 1500s to the early 1900s; see Figure 10.12), and the Philippines were occupied by the United States from 1898 to 1946. During World War II, much of the region was occupied by Japan. By the late twentieth century, occupation and domination by outsiders had ended and the region was profiting from selling manufactured goods to its former colonizers.

The Peopling of Southeast Asia

Australo-Melanesians groups of hunters and gatherers who moved from the present northern Indian and Burman parts of southern Eurasia to the exposed landmass of Sundaland about 60,000 to 40,000 years ago

Austronesians Mongoloid groups of skilled farmers and seafarers from southern China who migrated south to various parts of Southeast Asia between 10,000 and 5000 years ago

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of Southeast Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

From where did those who populated this region in prehistory come?

From where did those who populated this region in prehistory come?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How did Hinduism and Buddhism arrive in Southeast Asia?

How did Hinduism and Buddhism arrive in Southeast Asia?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Which European countries established colonies in Southeast Asia?

Which European countries established colonies in Southeast Asia?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

During World War II, Japan conquered which parts of Southeast Asia?

During World War II, Japan conquered which parts of Southeast Asia?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What has been the consequence of exposure to Agent Orange for many rural Vietnamese and Laotian people?

What has been the consequence of exposure to Agent Orange for many rural Vietnamese and Laotian people?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Diverse Cultural Influences

Over the last several thousand years, Southeast Asia has been and continues to be shaped by a steady circulation of cultural influences, both internal and external. Overland trade routes and the surrounding seas brought traders, religious teachers, and sometimes even invading armies from China and India, as well as Arab armies from southwest Asia. These newcomers brought religions, trade goods (such as cotton textiles), and food plants (such as mangoes and tamarinds) deep into the Indonesian and Philippine archipelagos and throughout the mainland. The monsoon winds, which blow from the west in the spring and summer, facilitated access for merchant ships from South Asia and the Persian Gulf. The ships sailed home on winds blowing from the east in the autumn and winter, carrying spices, bananas, sugarcane, silks, and other East and Southeast Asian items, as well as people, to the wider world.

Religious Legacies

Spatial patterns of religion in Southeast Asia reveal an island–mainland division that reflects the history of influences from India, China, Southwest Asia, and Europe. Both Hinduism and Buddhism arrived thousands of years ago via monks and traders who traveled by sea and along overland trade routes that connected India and China through Burma (see Figure 10.13B). Many early Southeast Asian kingdoms and empires switched back and forth between Hinduism and Buddhism as their official religion. Spectacular ruins of these Hindu–Buddhist empires are scattered across the region; the most famous is the city of Angkor in what is now Cambodia. At its zenith in the 1100s, Angkor was among the largest cities in the world, and its ruins are now a World Heritage Site (see Figure 10.16A). Today, Buddhism dominates mainland Southeast Asia, while Hinduism remains dominant only on the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lombok.

In Vietnam, people practice a mix of Buddhist, Confucian, and Taoist customs that reflect the thousand years (ending in 938 c.e.) when Vietnam was part of various Chinese empires. China’s traders and laborers also brought cultural influences to scattered coastal zones throughout Southeast Asia.

Islam is now dominant in most of the islands of Southeast Asia. Islam came mainly through South Asia after India was conquered by Mughals in the fifteenth century. Muslim spiritual leaders and traders converted many formerly Hindu–Buddhist kingdoms in Indonesia, Malaysia, and parts of the southern Philippines, where Islam is still dominant. Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion in Timor-Leste and in most of the Philippines, colonized respectively by Portugal and Spain.

European Colonization

Over the last five centuries, several European countries established colonies or quasi-colonies in Southeast Asia (Figure 10.12). Drawn by the region’s fabled spice trade, the Portuguese established the first permanent European settlement in Southeast Asia at the port of Malacca, Malaysia, in 1511. Although better ships and weapons gave the Portuguese an advantage, their anti-Islamic and pro-Catholic policies provoked strong resistance in Southeast Asia. Only on the small island of Timor-Leste did the Portuguese establish Catholicism as the dominant religion.

Arriving in 1521, by 1540 the Spanish had established trade links across the Pacific between the Philippines and their colonies in the Americas (see Figure 10.13C). Like the Portuguese, they practiced a style of colonial domination grounded in Catholicism, but they met less resistance because of their greater tolerance of non-Christians. The Spanish ruled the Philippines for more than 350 years; as a result, except for the southernmost islands, the Philippines is the most deeply Westernized and certainly the most Catholic part of Southeast Asia.

The Dutch were the most economically successful of the European colonial powers in Southeast Asia. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, they extended their control of trade over most of what is today called Indonesia, known at the time as the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch became interested in growing cash crops for export. Between 1830 and 1870, they forced indigenous farmers to leave their own fields and work part time without pay on Dutch coffee, sugar, and indigo plantations. The resulting disruption of local food production systems caused severe famines and provoked resistance that often took the form of Islamic religious movements. Resistance movements hastened the spread of Islam throughout Indonesia, where the Dutch had made little effort to spread their Protestant version of Christianity.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the British established colonies at key ports on the Malay Peninsula. They held these ports both for their trade value and to protect the Strait of Malacca, the shortest passage for sea trade between Britain’s empire in India and China. In the nineteenth century, Britain extended its rule over the rest of modern Malaysia in order to benefit from Malaysia’s tin mines and plantations. Britain also added Burma to its empire, which provided access to forest resources and overland trade routes into southwest China.

The French first entered Southeast Asia as Catholic missionaries in the early seventeenth century. They worked mostly in the eastern mainland area in the modern states of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. In the late nineteenth century, spurred by rivalry with Britain and other European powers for access to the markets of nearby China, the French formally colonized the area, which became known as French Indochina.

In all of Southeast Asia, the only country not to be colonized by Europe was Thailand (then known as Siam). Like Japan, it protected its sovereignty through both diplomacy and a vigorous drive toward European-style modernization; Thailand retains a titular emperor to this day.

Struggles for Independence

Agitation against colonial rule began in the late nineteenth century when Filipinos fought first against Spain in 1896. They then resisted control by the United States, which began in 1898 after the Spanish-American War (see Figure 10.12B). However, the Philippines and the rest of Southeast Asia did not win independence until after World War II (Figure 10.12A). By then, Europe’s ability to administer its colonies had been weakened by the devastation of the war, during which Japan had conquered most of the parts of Southeast Asia that had been controlled by Europe and the United States (see Figure 10.13D). Japan held these lands until it was defeated by the United States at the end of the war. By the mid-1950s, the colonial powers had granted self-government to most of the region, and all of Southeast Asia was independent by 1975.

The Vietnam War

The most bitter battle for independence took place in French Indochina (the territories of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, acquired in the nineteenth century). Although all three became nominally independent in 1949, France retained political and economic power over them. Various nationalist leaders, most notably Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh, headed resistance movements against continued French domination. The resistance leaders accepted military assistance from Communist China and the Soviet Union, even though they were not doctrinaire communists and despite ancient antipathies toward China for its previous millennia of domination. In this way, the Cold War was brought to mainland Southeast Asia.

domino theory a foreign policy theory that used the idea of the domino effect to suggest that if one country “fell” to communism, others in the neighboring region were also likely to fall

More than 4.5 million people died during the Vietnam War, including more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers. Another 4.5 million on both sides were wounded, and bombs, napalm, and chemical defoliants ruined much of the Vietnamese environment. Land mines continue to be a hazard to this day, and the effects of the highly toxic defoliant known as Agent Orange are still producing debilitating birth defects among many rural Vietnamese and Laotian people (see Figure 10.13E). The withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973 ranks as one of the most profound defeats in U.S. history. After the war, the United States crippled Vietnam’s recovery by imposing severe economic sanctions that lasted until 1993. Since then, the United States and Vietnam have become significant trading partners.

The “Killing Fields” in Cambodia

In Cambodia, where the Vietnam War had spilled over the border, a particularly violent revolutionary faction called the Khmer Rouge seized control of the government in 1975. Inspired by the vision of a rural communist society, they attempted to destroy virtually all traces of European influence. They targeted Western-educated urbanites in particular, forcing them into labor camps, where more than 2 million Cambodians—one-quarter of the population—starved or were executed in what became known as the “killing fields.”

In 1979, Vietnam deposed the Khmer Rouge and ruled Cambodia through a puppet government until 1989. A 2-year civil war then ensued. Despite a major UN effort to establish a multiparty democracy in Cambodia throughout the 1990s, the country remained plagued by political tensions between rival factions and by government corruption. In March 2009, Kang Kek Iew, the first of the Khmer Rouge leaders to be tried for war crimes and genocide, was forced to listen to and watch lengthy accounts of the torture of men, women, and children that he supervised. He was convicted in 2010 and sentenced to 35 years in prison. Most operatives in the killing fields will never be prosecuted.  223. CAMBODIAN HIP-HOP ARTIST TELLS STORY THROUGH RAP

223. CAMBODIAN HIP-HOP ARTIST TELLS STORY THROUGH RAP

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Over the last five centuries, several European countries, and later the United States and Japan, established colonies or quasi-colonies that covered almost all of Southeast Asia.

Over the last five centuries, several European countries, and later the United States and Japan, established colonies or quasi-colonies that covered almost all of Southeast Asia. Colonial rule in Southeast Asia began in 1511 with the Portuguese and came to a violent end in Vietnam and Cambodia, where war took the lives of millions, including more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers.

Colonial rule in Southeast Asia began in 1511 with the Portuguese and came to a violent end in Vietnam and Cambodia, where war took the lives of millions, including more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers.