Economic and Political Issues

Initially, trade among countries within the region was inhibited by the fact that they all exported similar goods—primarily food and raw materials—and traditionally imposed tariffs against one another. They imported consumer products, industrial materials, machinery, and fossil fuels mostly from the developed world. Several decades ago, the economic and political situation in the region changed dramatically, when during the 1990s, Southeast Asian countries had some of the highest economic growth rates in the world. The growth was based on an economic strategy that emphasized the export of manufactured goods—initially clothing and then more sophisticated technical products. In the late 1990s, though, economic growth stagnated; as people’s financial expectations were dashed, political instability increased. The high level of corruption revealed by the crisis resulted in stronger calls for democratization, which has expanded unevenly across the region.

Strategic Globalization: State Aid and Export-Led Economic Development

Geographic Insight 2

Globalization and Development: Globalization has brought spectacular economic successes and occasional dramatic economic declines. Urban incomes soar during periods of growth, but the poor are vulnerable during periods of global economic decline.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, some national governments in Southeast Asia created strong and sustained economic expansion by emulating two strategies for economic growth pioneered earlier by Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea (Chapter 9). One was the formation of state-aided market economies. National governments in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and to some extent, the Philippines, intervened strategically in financial institutions to make sure that certain economic sectors developed; in addition, investment by foreigners was limited so that the governments could have more control over the direction of the economy. The other strategy was export-led economic development, which focused investment on industries that manufactured products for export, primarily to developed countries. These strategies amounted to a limited and selective embrace of globalization in that global markets for the region’s products were sought but foreign sources of capital were not.

These approaches were a dramatic departure from those used in other developing areas. In Middle and South America and parts of Africa, postcolonial governments relied on import substitution industries that produced manufactured goods mainly for local use. By contrast, export-led industrial growth allowed Southeast Asia to earn much more money in the vastly larger markets of the developed world. Standards of living increased markedly, especially in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand. Other important results of Southeast Asia’s success were a decrease in wealth disparities and improvements in vital statistics: lower population growth rates, lower infant and maternal mortality rates, and longer life expectancy rates.

Export Processing Zones

In the 1970s, some governments in the region began adopting an additional strategy for encouraging economic development. This time, they sought foreign sources of capital, but the places those sources could invest in were limited to specially designated free trade areas. Such Export Processing Zones (EPZs) (see the discussion in Chapter 3) are places in which foreign companies can set up their facilities using inexpensive, locally available labor to produce items only for export (maquiladoras in Mexico are an example of companies set up by foreign firms). Taxes are eliminated or greatly reduced so long as the products are re-exported, not sold in-country. Since the 1970s, EPZs have expanded economic development in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines and are now used widely in China and Middle and South America.

The Feminization of Labor

feminization of labor the increasing employment of women in both the formal and informal labor force, usually at lower wages than those of men

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why do many employers prefer workers to be young, single women?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Working Conditions

In general, the benefits of Southeast Asia’s “economic miracle” have been unequally apportioned. In the region’s new factories and other enterprises, it is not unusual for assembly-line employees to work 10 to 12 hours per day, 7 days per week, for less than the legal minimum wage, and without benefits. Labor unions that typically would address working conditions and wage grievances are frequently repressed by governments; international consumer pressure to improve working conditions at U.S. companies like Nike has been only partially effective. By 2010, for example, Nike had sidestepped the entire issue of customer complaints by outsourcing its manufacturing to non-U.S. contractors in the region. U.S. fair labor NGOs pursued one Nike subcontractor in Jakarta, Indonesia, where workers were required to work an hour a day, off the books, in order to meet production quotas. A $1 million settlement will give each of the 4500 workers $222. There are more than 160,000 workers for Nike subcontractors in Indonesia alone, so this settlement is but a drop in the bucket.

A much more powerful force that is improving working conditions and driving up pay is the growth of the service sector throughout the region. In Singapore, the Philippines, and Thailand, the service sector already dominates the economy in employment and as a percentage of GDP. In Cambodia and Timor-Leste, the service sector contributes, respectively, 40 percent and 55 percent of the country’s GDP, though agriculture still employs the majority of workers in both countries. In other countries in the region, the service sector is approaching parity with the industrial or agricultural sectors. Only Brunei is still dominated by its industrial sector, which is entirely based on oil production. Many service sector jobs require at least a high school education; competition for the smaller number of educated workers means that wages and working conditions are already better than in manufacturing and are likely to improve faster.

Economic Crisis and Recovery: The Perils of Globalization

The economic crisis that swept through Southeast Asia in the late 1990s forced millions of people into poverty and changed the political order in some countries. A major cause of the crisis was the lifting of controls on Southeast Asia’s once highly regulated financial sector. There were some geographic aspects to this crisis: the banks involved were located primarily in Singapore and the major cities of Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. These were also the countries to feel the immediate effects of the crisis. Eventually the effects filtered into the hinterland, and workers in remote areas lost jobs and access to essentials.

Deregulating Investment

As part of a general push by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to open national economies to the free market, Southeast Asian governments relaxed controls on the financial sector in the 1990s. Soon, Southeast Asian banks were flooded with money from investors in the rich countries of the world who hoped to profit from the region’s growing economies. Flush with cash and newfound freedoms, the banks often made reckless decisions. For example, bankers made risky loans to real estate developers, often for high-rise office building construction. As a result, many Southeast Asian cities soon had far too much office space, with millions of investment dollars tied up in projects that contributed little to economic development.

crony capitalism a type of corruption in which politicians, bankers, and entrepreneurs, sometimes members of the same family, have close personal as well as business relationships

The cumulative effect of crony capitalism and the lifting of controls on banks was that many ventures failed to produce any profits at all. In response, foreign investors panicked, withdrawing their money on a massive scale. In 1996, before the crisis, there was a net inflow of U.S.$94 billion to Southeast Asia’s leading economies. In 1997, inflows had ceased and there was a net outflow of U.S.$12 billion.

The IMF Bailout and Its Aftermath

The IMF made a major effort to keep the region from sliding deeper into recession by instituting reforms designed to make banks more responsible in their lending practices. The IMF also required structural adjustment policies (SAPs; in Chapter 3), which required countries to cut government spending (especially on social services) and abandon policies intended to protect domestic industries.

After several years of economic chaos, and much debate over whether the IMF bailout helped or hurt a majority of Southeast Asians, economies began to recover. In the largest of the region’s economies, growth resumed by 1999; by 2006, the crisis, while still an ominous reminder of the risks of globalization, had been more or less overcome.

The Impact of China’s Growth

During the Southeast Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand lost out to China in attracting new industries and foreign investors. By the early 2000s, China attracted more than twice as much foreign direct investment (FDI) as Southeast Asia. However, China’s growth also became an opportunity for Southeast Asia. Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines “piggybacked” on China’s growth by winning large contracts to upgrade China’s infrastructure in areas such as wastewater treatment, gas distribution, and shopping mall development.

Southeast Asia has also used its comparative advantages over China to attract investment. In poorer countries, such as Vietnam, wages have remained lower than in China. This has attracted investments in low-skill manufacturing that had been going to China. Meanwhile, some of the region’s wealthier countries—Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand—have been positioning themselves as locations that offer more highly skilled labor and greater high-tech infrastructure than China does.

The Global Recession Beginning in 2007

The region was hit again by the effects of the global recession that became full blown in the region by 2008. Growth slowed markedly because high oil and food prices restricted disposable cash worldwide, and consumers in wealthy countries (especially the United States and the EU countries, which are Southeast Asia’s biggest trade partners) faced crippling debt that seriously curtailed their spending. By late 2009, East and Southeast Asia appeared to be recovering. In part, the recovery was based on the pent-up demand for goods and services within the domestic economies of China and Southeast Asia, where consumers now had some disposable cash. Southeast Asia’s ability to respond to this demand was facilitated by policies that opened up intraregional trade and access to China. The recovery was carefully modulated by relatively tight trade and monetary regulations aimed at controlling inflation. Older strategies, such as the establishment of EPZs, were expanded to attract additional multinational corporations to Southeast Asia.

But the positive developments of 2009 did not last. By 2012, financial troubles in Europe and slow recoveries in the United States and Japan all lowered demand for Southeast Asian products. Singapore, with its highly sophisticated economy that is based on its banking services and the transfer of goods through its giant port, is particularly susceptible to slowdowns in rich countries. Manufacturing countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand also fare best when there is demand for their products in international markets. Cambodia, Laos, and Burma are still reliant on raw material exports to places like China. Meanwhile, China needed to restructure and reorganize investment, labor migration, and environmental policies in order to fend off civil unrest and loss of economic momentum. To do so, it began rebalancing its economy with the aim of encouraging internal sales of Chinese-produced products rather than those produced abroad. This further reduced the demand for raw materials and manufactured goods from Southeast Asia.

Regional Trade and ASEAN

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) an organization of Southeast Asian governments that was established to further economic growth and political cooperation

Regional Integration

ASEAN started in 1967 as an anti-Communist, anti-China association, but it now focuses on agreements that strengthen regional cooperation, including agreements with China. One example is the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapons–Free Zone Treaty signed in December 1995. Another is the ASEAN Economic Community, or AEC, a trade bloc patterned after the North American Free Trade Agreement and the European Union. Now, ASEAN focuses on increasing trade between all ten members of the association.

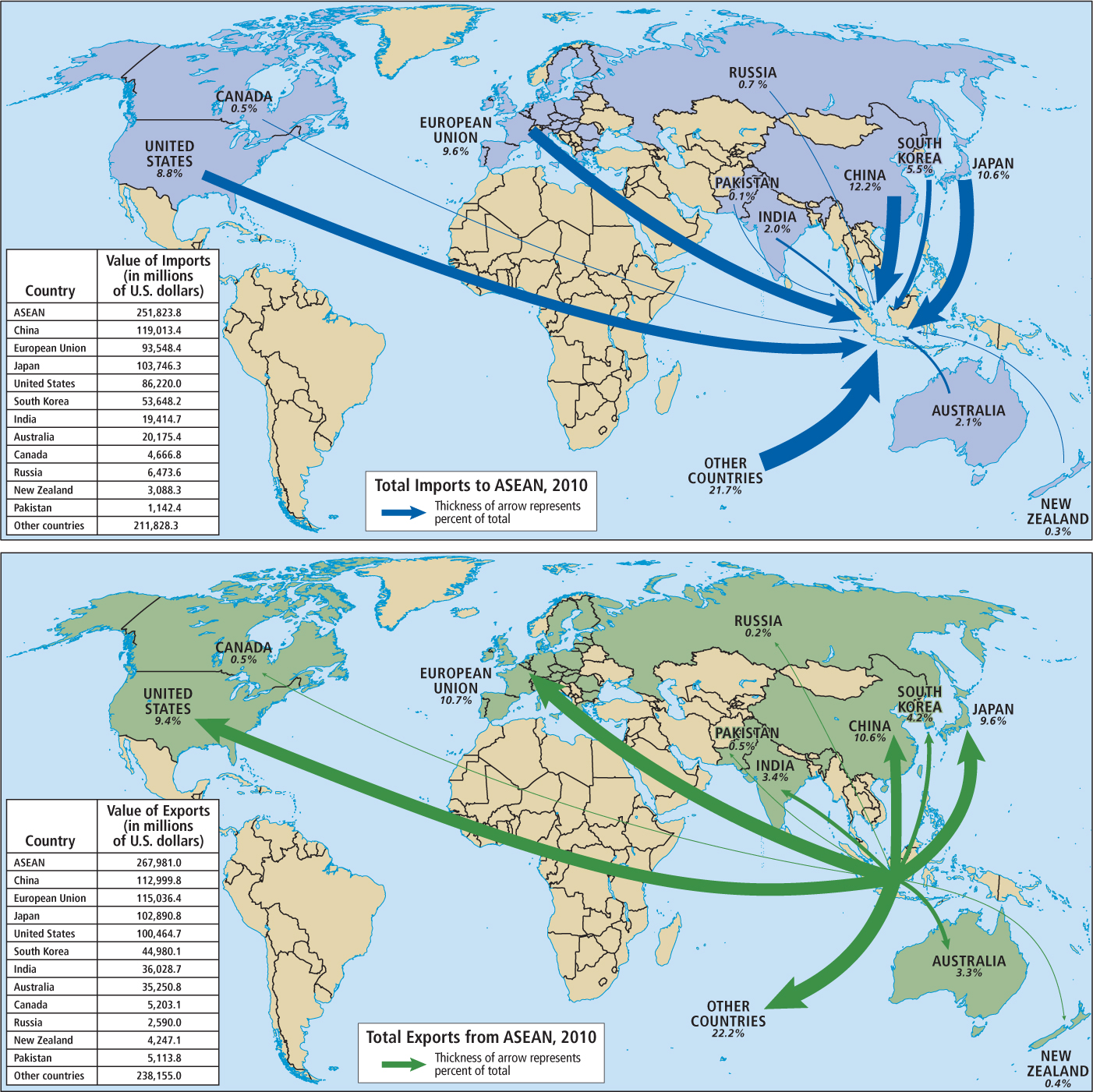

In January of 2010, ASEAN established the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) to facilitate regional trade. By that same year, the total intraregional trade between ASEAN countries was more than trade with any one outside country or region, with ASEAN countries representing 25.8 percent of total imports and 25 percent of total exports (Figure 10.15). By 2012, a variety of other issues were being addressed, such as the free flow of services, skilled labor, investment and capital. Consumer protection, intellectual property rights, and leveling the playing field for competition were also receiving attention. ASEAN’s overall goals are to develop a sustainable regional economic community and to decrease development gaps between and within ASEAN member states. Externally, ASEAN has ratified free trade agreements with Australia, New Zealand, China, India, Japan, and South Korea.

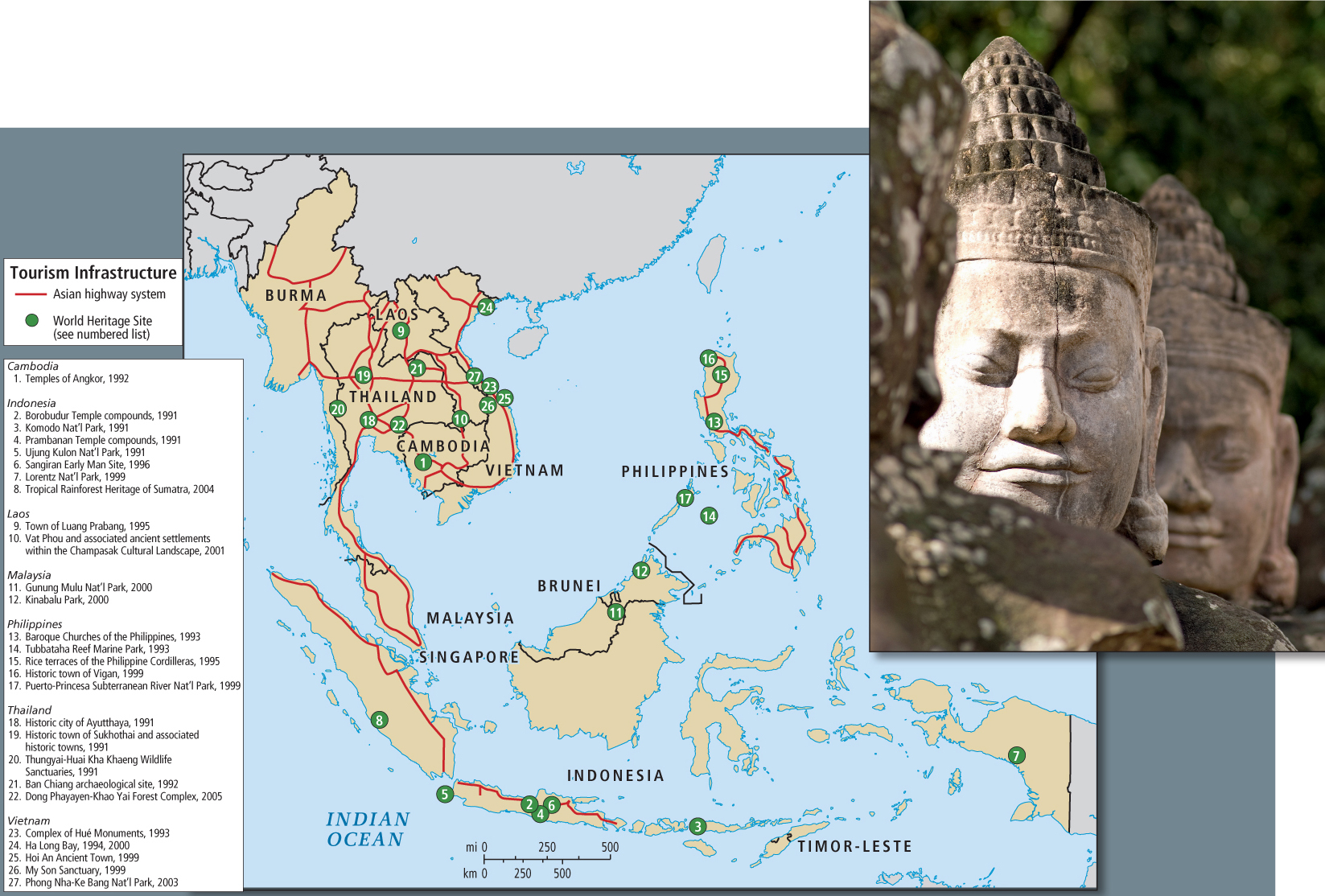

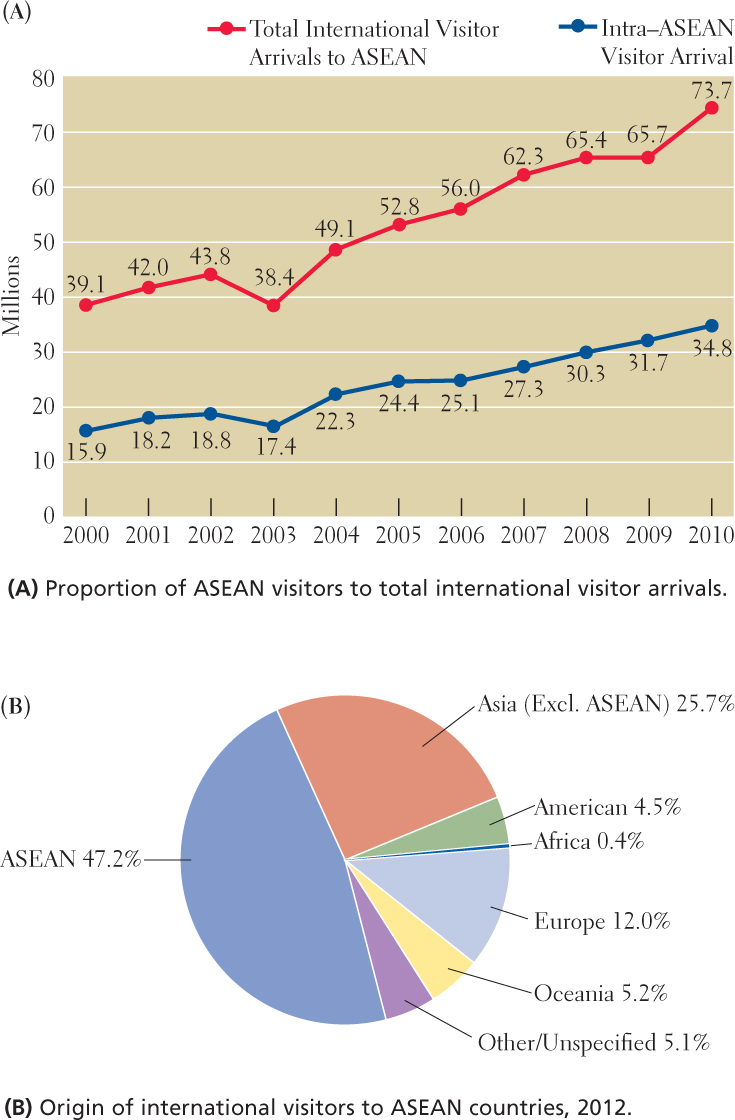

Tourism

International tourism is an important and rapidly growing economic activity in most Southeast Asian countries (Figure 10.16). Between 1991 and 2001, the number of international visitors to the region doubled to more than 40 million; in 2010, international visitors reached over 73.7 million. As in other trade matters, Southeast Asians are themselves increasingly touring neighboring countries; in 2010, for example, 34.8 million tourists to ASEAN countries were from within the region (Figure 10.17). This is a positive trend because familiarity between neighbors lays the groundwork for various forms of regional cooperation, such as infrastructure improvements.

In response to its popularity with global and regional tourists, ASEAN members have been working to improve the region’s transportation infrastructure. One such project is the Asian Highway, a web of standardized roads that loop through the mainland and connect it with Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia (the latter via ferry) (see the Figure 10.16 map). Eventually, the Asian Highway will facilitate ground travel through 32 Eurasian countries from Russia to Indonesia and from Turkey to Japan.

The surge of tourism in Southeast Asia has also raised concerns about becoming too dependent on an industry that leaves economies vulnerable to events that precipitously stop the flow of visitors (natural disasters, political upheavals), or that leave local people vulnerable to the sometimes destructive demands of tourists (see the discussion of sex tourism). Examples of disasters are the tsunami of December 2004 that killed several thousand international tourists in Thailand and Indonesia, and various human-made disasters such as the terrorist bombings in Bali (2002, 2005) and in southern Thailand (2006, 2012). In addition, tourism can divert talent from contributing to national development, as the following vignette illustrates.

VIGNETTE

Tan Phuc waits patiently for the mechanic to mount the new rear tire on his Chinese-made 125cc motorcycle. He is a motorcycle tour guide in Vietnam who likes to take his clients to places along Highway 14 in the Central Highlands, close to the historic Ho Chi Minh Trail. Tan’s current client, a Dutch tourist, has spent 3 days filling his digital camera with images of vast coffee plantations covered in snowy blossoms, of silkworms frying in oil while their cocoons are unwound and spun into silk thread, and of indigenous minority children who met the gaze of his camera with casual curiosity. Tan finds his clients in bus stations and backpacker hostels and negotiates a daily rate for tours—usually between U.S.$50 and U.S.$75, not insignificant in a country that has an average per capita annual income of U.S.$2790.

Tan Phuc’s life has always been subject to global forces. As a child in the Mekong Delta, he sold produce to U.S. soldiers at a nearby base. During the war, he lost his brother, a soldier for South Vietnam; after the war, his father spent 10 years in a Communist reeducation camp. Even with the hardships, Tran obtained an education. But when the annual inflation rate of 400 percent shrank his salary as a high school math teacher, Tran could not adequately meet his family’s needs. Like other skilled Vietnamese people, Tran took advantage of Vietnam’s transition to a market economy and established a business that caters to tourists. This means that he, along with many other educated Vietnamese people, no longer works in occupations crucial to Vietnam’s future, like education. [Source: The field work of Karl Russell Kirby. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

230. BANKERS, ANALYSTS SEE RESURGENT ASIA 10 YEARS AFTER ECONOMIC CRISIS

230. BANKERS, ANALYSTS SEE RESURGENT ASIA 10 YEARS AFTER ECONOMIC CRISIS

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 2Globalization and Development Southeast Asia has had long periods of strong economic growth punctuated by brief but dramatic periods of decline (recession).

Geographic Insight 2Globalization and Development Southeast Asia has had long periods of strong economic growth punctuated by brief but dramatic periods of decline (recession). Incomes have increased significantly, but many poor people remain highly vulnerable to periods of global economic decline, when jobs, food, and adequate living quarters are hard to come by.

Incomes have increased significantly, but many poor people remain highly vulnerable to periods of global economic decline, when jobs, food, and adequate living quarters are hard to come by. Regional integration, including the tourism infrastructure of the region, is expected to foster growth and encourage cooperation with China.

Regional integration, including the tourism infrastructure of the region, is expected to foster growth and encourage cooperation with China.

Pressures For and Against Democracy

Geographic Insight 3

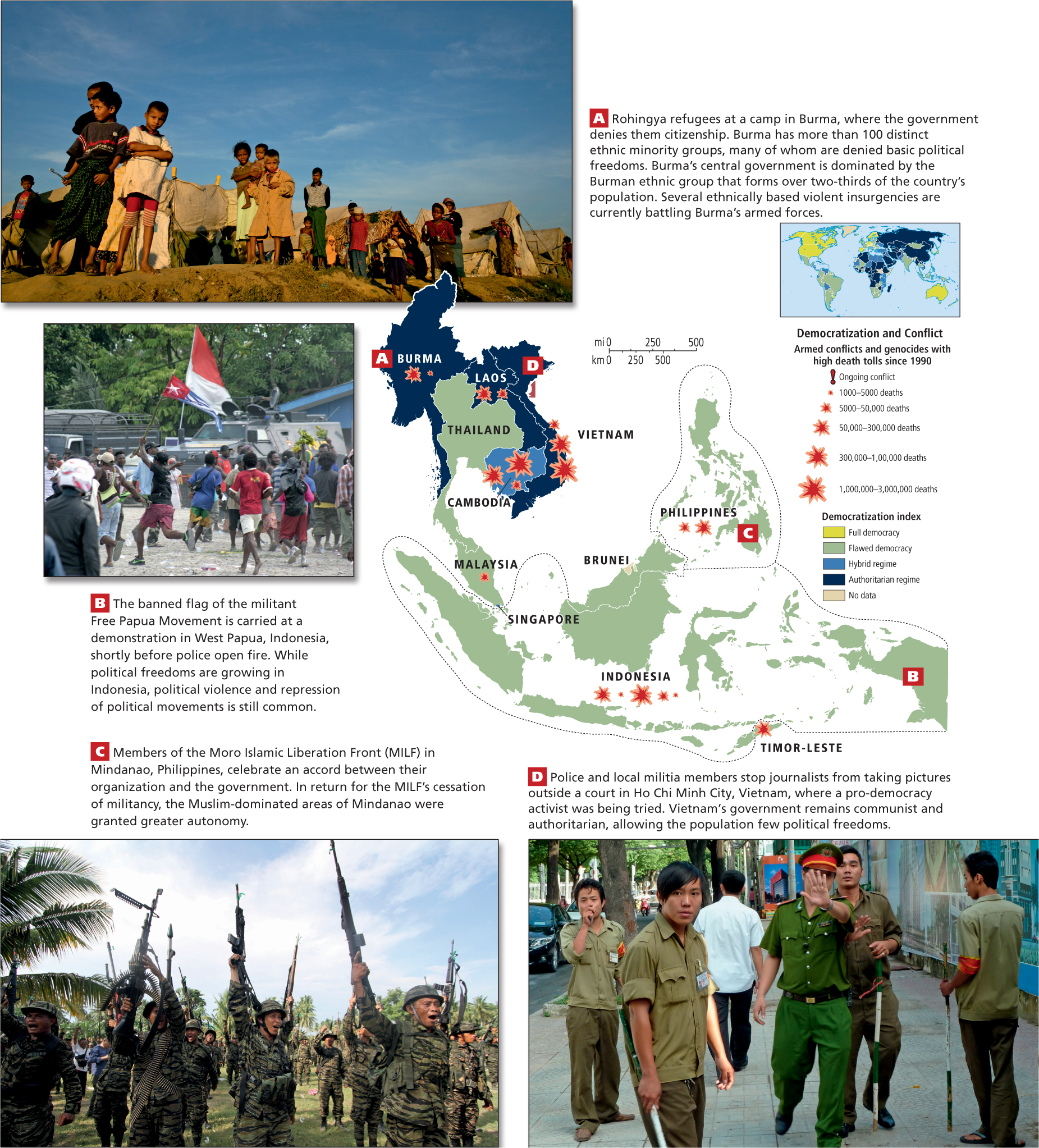

Power and Politics: Militarism, corruption, and favoritism are recurring issues in Southeast Asia. Although modernization and prosperity have brought significant increases in democratic participation, there have also been reversals, especially during periods of economic downturn. These sometimes result in violence, often against ethnic minorities.

Movements toward democracy have been uneven in Southeast Asia. Across the region, there are significant barriers to democratic participation (refer to the Figure 10.18 map), but the types of barriers vary. These are all countries with multicultural populations who share relatively few common characteristics. Efforts to smooth over these differences take many forms; Indonesia’s solution, Pancasila, is discussed below. Several countries are plagued with violent conflict: the repressive military regime in Burma, which has controlled with an iron fist and thwarted open elections and pro-democracy demonstrations for more than 20 years, began to allow small but possibly significant changes in 2012; and Thailand, long regarded as the most stable democracy in the region, now is dealing with deep divisions between supporters of a royalist military on the right and a large populist movement on the left. The situation is complicated by a rebellion and terrorism by Islamic militants in southern tourist zones. Indonesia has tried to use democratic reforms to reduce the tensions that in the past produced violence in many of its distinctive islands, but faces demoralizing setbacks in Aceh province in Sumatra. The Philippines, plagued with a long line of dictators, now has elected governments that have resolved many problems (except low wages and high rates of unemployment); however, militant Muslims in the southern islands continue an insurgency that periodically devolves into violence.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about power and politics in Southeast Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What details in this picture are clues that these people are refugees?

What details in this picture are clues that these people are refugees?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why would a government ban a flag?

Why would a government ban a flag?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What does this picture suggest about the MILF?

What does this picture suggest about the MILF?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Can Democracy Work in Indonesia?

An important yet still tentative shift toward democracy took place in Indonesia in the wake of the economic crisis of the late 1990s. After three decades of semidictatorial rule by President Suharto, the economic crisis spurred massive demonstrations that forced Suharto to resign. For more than a decade, democratic parliamentary and presidential elections brought a new political era to the country, but by 2012, corruption scandals had erupted among ministers in President Yudhoyono’s government (Yudhoyono’s campaigned in 2009 on a platform of reducing corruption), and Yudhoyono was proving to be an indecisive leader.

Indonesia is the largest country in Southeast Asia, and the most fragmented—physically, culturally, and politically. It comprises more than 17,000 islands (3000 of which are inhabited), stretching over 3000 miles (8000 kilometers) of ocean. It is also the most culturally diverse, with dozens of ethnic groups and multiple religions. Although Indonesia has the largest Muslim population in the world, there are also many Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, and adherents of various folk religions. With all these potentially divisive forces, many wonder whether this multi-island country of 238.2 million might be headed for disintegration.

Until the end of World War II, Indonesia was not a nation at all but rather a loose assemblage of distinct island cultures, which Dutch colonists managed to hold together as the Dutch East Indies. When Indonesia became an independent country in 1945, its first president, Sukarno, hoped to forge a new nation out of these many parts, founded on a fairly strong communist ideology. To that end, he articulated a national philosophy known as Pancasila, which aimed at holding the disparate nation together, primarily through nationalism and concepts of religious tolerance. In 1965, during the height of the Cold War, Suharto, a staunchly anti-Communist general in the Indonesian army, ousted Sukarno in a coup and ruled the country for another 33 years. It is now clear that Suharto’s long regime was responsible for a purge of suspected Communists, during which as many as a million people were killed.

Encouraging Cohesiveness with Government Policies in Indonesia

Despite his abrupt removal from office, Sukarno’s unifying idea of Pancasila endures as a central theme of life in Indonesia (and less formally throughout the region). Pancasila embraces five precepts: belief in God, and the observance of conformity, corporatism (often defined as “organic social solidarity with the state”), consensus, and harmony. These last four precepts could be interpreted as discouraging dissent or even loyal opposition, and they seem to require a perpetual stance of boosterism. For many Indonesians, the strength of Pancasila is the emphasis on harmony and consensus that seems to ensure there will never be a religiously based government. Others note that conformity and corporatism counteract the extreme ethnic diversity and geographic dispersion of the country. But conformity and corporatism have also had a chilling effect on participatory democracy and on criticism of the government, the president, and the army. Indeed, the first orderly democratic change of government did not take place until national elections in 2004. Since then, there have been several peaceful elections, and the government uneasily allows citizens to publicly protest policies (see Figure 10.18B). But corruption remains a threat and there is a feeling of nostalgia for the Suharto model of authoritarian government.

resettlement schemes government plans to move large numbers of people from one part of a country to another to relieve urban congestion, disperse political dissidents, or accomplish other social purposes; also called transmigration

The failure of the cohesiveness sought by Pancasila is particularly troubling in the far western province of Aceh, in the north of Sumatra. Conflicts there originally developed because most of the wealth yielded by Aceh’s resources, especially oil, was going to the central government in Jakarta. The Acehnese people protested what they saw as the expropriation of oil without compensation. Jakarta sent the military to quell rebellion. Protestors, especially young people, viewed the military presence as adding insult to injury. Many were accused of resorting to violence and were hunted down, charged with terrorism, and jailed or worse. The conflict seemed unresolvable. Then in 2004, the earthquake and tsunami in Aceh, which killed more than 170,000 Acehnese, suddenly brought many outside disaster relief workers to Sumatra because the Indonesian government was incapable of rendering sufficient aid to the victims. Global press coverage of the relief effort mentioned the recent political violence; this created a powerful incentive for separatists and the government to cooperate in order to receive outside aid.

A resulting peace accord signed in 2005 brought many former combatants into the political process as democratically elected local leaders. Separatists laid down their arms. But when global press coverage stopped, the implementation of the peace accord ceased and another outside force crept into the situation. Islamic militants, who favor Shari‘a, are gaining adherents among disaffected Acehnese youth. Shari‘a (discussed more completely in Chapter 6) is usually subject to the laws of the land, but can be extreme, especially regarding the rights of women. Shari‘a was never previously practiced in Aceh, and moderate leaders in Aceh are worried.

Southeast Asia’s Authoritarian and Militaristic Tendencies

Despite the ebb and flow of participatory democracy in Indonesia, Thailand, and most recently in Burma (March 2012), authoritarianism backed by a strong military is still a powerful force in Southeast Asia. Authoritarianism is rationalized primarily as a counter to destabilization caused by “too much” democracy. For example, in 2006, the military took over Thailand’s government after a corrupt but charismatic prime minister marshaled masses of protestors (Red Shirts) who took to the streets, disrupting business and the lucrative tourism industry. Despite recent elections, the matter remains unresolved and the Red Shirts periodically take over the streets of Bangkok (see coverage in the Subregion section).

In the far south of Thailand, where Islamic militants have set off car bombs in European tourism areas, there are calls for military intervention. Undemocratic socialist regimes still control Laos and Vietnam (see Figure 10.18D); as of 2012, the military dictatorship running Burma has relaxed only slightly (see further coverage). Cambodia’s democracy is precarious, and violence there is common. Brunei is an authoritarian sultanate. Even in the Philippines, the region’s oldest democracy, powerful and corrupt leaders have subverted the democratic process repeatedly. The wealthier and usually stable countries of Malaysia and Singapore continue to use authoritarian versions of democracy.

Some Southeast Asian leaders, such as Singapore’s former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, have argued that Asian values are not compatible with Western ideas of democracy. These leaders assert that Asian values are grounded in the Confucian view that individuals should be submissive to authority, so Asian countries should avoid the highly contentious public debate of open electoral politics. Nevertheless, when confronted with governments that abuse their power, people throughout Southeast Asia have not submitted, but rebelled (see Figures 10.18A, B). Even in Singapore, the Western-educated son of Lee Kuan Yew, Lee Hsien Loong, who is now prime minister, has expressed more interest in the growth of political freedoms than did his father.

In part, the inability of civilian-led governments to always keep the peace has given the military components of Southeast Asian governments continuing power. In virtually every country, the military has been called on to restore civil calm. Military rank is highly regarded: virtually every top elected official has had a military career. Even Aung San Suu Kyi, the advocate for peace and political freedoms in Burma, is the daughter of a military man. For these reasons, the military’s role in politics is likely to persist.

For all this emphasis on militarism, the countries of the region are unlikely to go to war against each other. However all are keeping an eye on the growing Chinese navy. As a region surrounded and divided by water, with thousands of miles of coastline, beefing up military prowess seems an obvious security measure. Also, the tsunami disaster in Sumatra in 2004 showed that no military organization in the region was able to effectively manage such a disaster. Not surprisingly, most countries recently have invested heavily in military equipment, primarily from Europe and the United States. In 2011, tiny, wealthy trade-centered Singapore, the biggest spender per capita on weapons, spent one quarter of its GDP on weapons; it now produces armored troop carriers for use at home and for export.

Terrorism, Politics, and Economic Issues

Like authoritarianism, terrorism has long loomed as a counterforce to political freedoms in this region. Terrorist violence short-circuits the public debate that is at the heart of democratic processes and appears to reinforce the need for authoritarian militaristic measures. However, it is important to recognize that terrorist movements often thrive in the context of both economic deprivation and political repression, two factors that are often interrelated. As is the case in the southern Philippines (see Figure 10.18C), terrorism seems to draw support from people who feel shut out from opportunities for economic advancement. Increasingly, the peaceful solution to terrorism seems to be to listen to both the political and economic desires of those who might be attracted to terrorism.

225. TERROR AND ISLAMIC STRUGGLE IN INDONESIA

225. TERROR AND ISLAMIC STRUGGLE IN INDONESIA

232. VIOLENCE IN THAILAND’S MUSLIM SOUTH INTENSIFIES

232. VIOLENCE IN THAILAND’S MUSLIM SOUTH INTENSIFIES

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Colonialism, a history of authoritarianism, deep cultural divisions, and a fractioned geography inhibit the equitable sharing of political power in Southeast Asia.

Colonialism, a history of authoritarianism, deep cultural divisions, and a fractioned geography inhibit the equitable sharing of political power in Southeast Asia. Pancasila is an example of movements, prevalent in most countries in the region, to find points of common values on which to base national unity.

Pancasila is an example of movements, prevalent in most countries in the region, to find points of common values on which to base national unity. Geographic Insight 3Power and Politics Generally speaking, those countries with the most developed economies have had the greatest increases in political freedoms, but there are both exceptions (Malaysia and Singapore) and countries that have undergone reversals (Thailand). Militarism, corruption, and favoritism are recurring issues in Southeast Asia.

Geographic Insight 3Power and Politics Generally speaking, those countries with the most developed economies have had the greatest increases in political freedoms, but there are both exceptions (Malaysia and Singapore) and countries that have undergone reversals (Thailand). Militarism, corruption, and favoritism are recurring issues in Southeast Asia. Violent conflict and even terrorism remain threats across the region. Nonetheless, the experience of recent years shows that movements toward more political freedom are strong.

Violent conflict and even terrorism remain threats across the region. Nonetheless, the experience of recent years shows that movements toward more political freedom are strong.