Sociocultural Issues

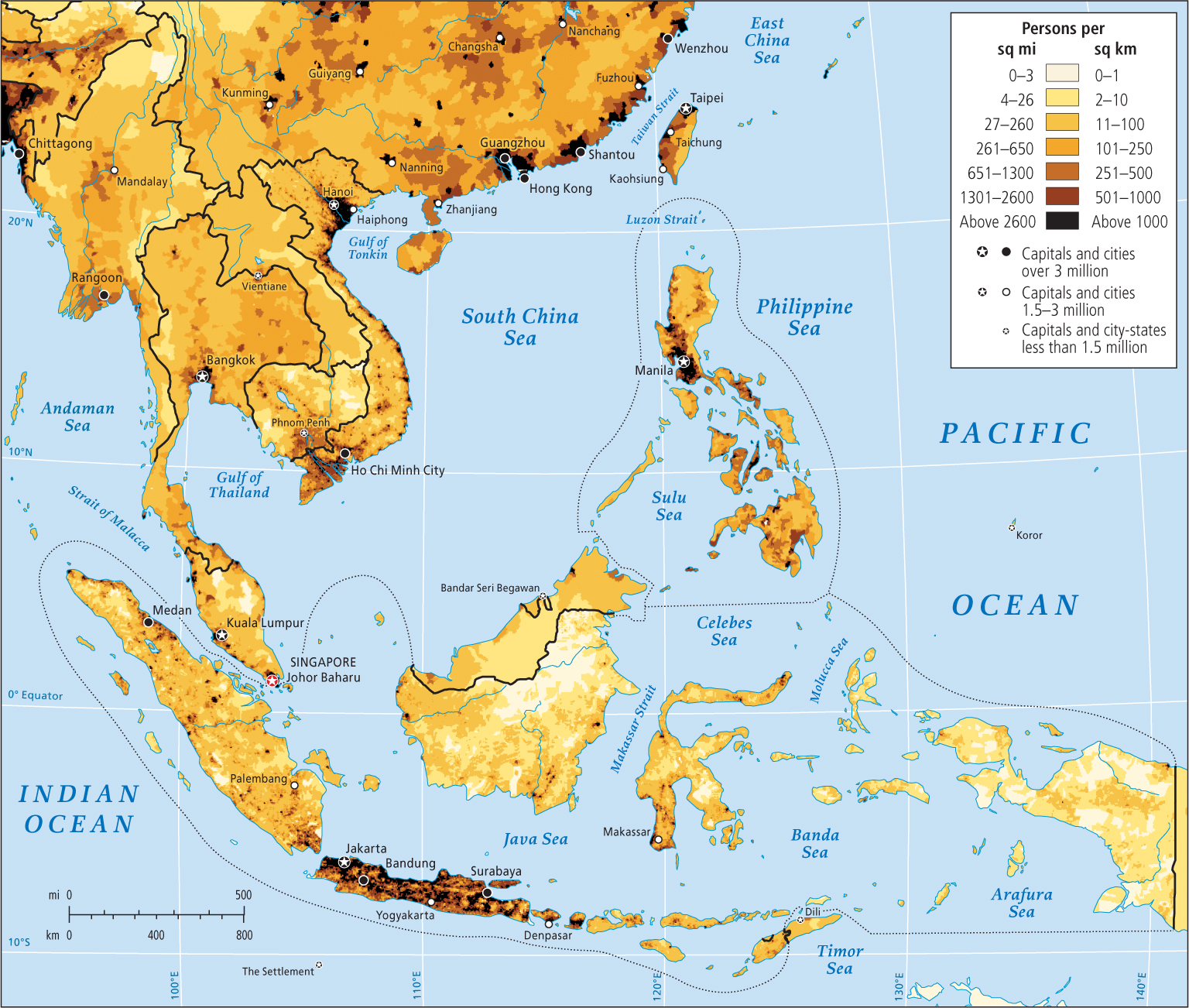

Southeast Asia is home to 602 million people (almost double the U.S. population) who occupy a land area that is about one-half the size of the United States. Because of the region’s long and complex history, the people in South east Asia have a great diversity of cultures and religious traditions.

Population Patterns

Geographic Insight 4

Population and Gender: Economic change has brought better job opportunities and increased status for women, who are then choosing to have fewer children. The improving role and status of women has increased awareness that sex trafficking is an abuse of human rights.

Southeast Asia’s population is large and growing, but economic development, changing gender roles, and population-control efforts are slowing the growth rate. At current rates, Southeast Asia’s population is projected to reach 796 million by 2050, by which time much of this population will live in cities (only 42 percent do now, though Singapore is 100 percent urban) (Figure 10.19). However, population projections could be inaccurate, both because rates of natural increase are continuing to slow markedly and because many Southeast Asians are migrating to find employment outside the region.

Population Dynamics

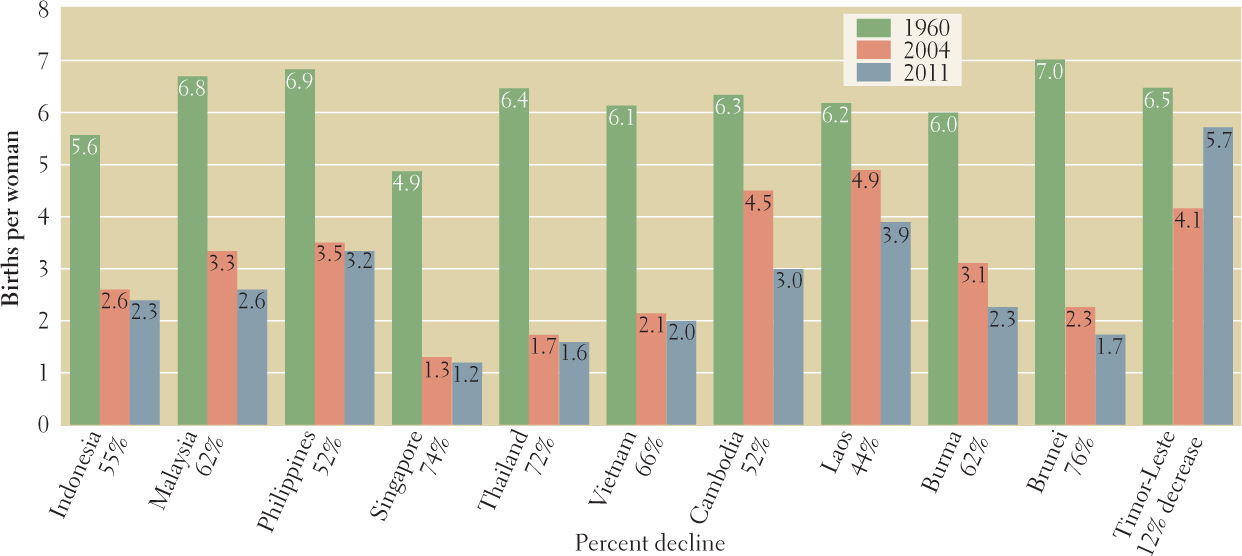

Population dynamics vary considerably among the countries of this region. The variety is due in part to differences in economic development, government policy, prescribed gender roles, and broader religious and cultural practices. Most countries are nearing the last stage of the demographic transition, where births and deaths are low and growth is minuscule or slightly negative. In the last several decades, overall fertility rates in Southeast Asia have dropped rapidly (Figure 10.20). Whereas women formerly had 5 to 7 children, they now have 1 to 3, with Laos (3.9) and Timor-Leste (5.7) being the major exceptions. However, because in most countries populations are still quite young (between one-quarter and one-third of the people are aged 15 years or younger), modest population growth is likely for several decades because so many are just coming into their reproductive years.

Brunei, Singapore, and Thailand have reduced their fertility rates so steeply—below replacement levels—that they will soon need to cope with aging and shrinking populations. Regionally, education levels are the highest in Singapore, where most educated women work outside the home at skilled jobs and professions. The Singapore government is now so concerned about the low fertility rate that it offers young couples various incentives for marrying and procreating.

An important source of population growth for Singapore is the steady stream of highly skilled immigrants that its vibrant economy attracts. Many of these immigrants come from elsewhere in the region, though the country also draws highly skilled workers from the United States and Europe. Singapore also attracts illegal immigrants from elsewhere in Southeast Asia, primarily in the building trades and low-wage services. Nearly all countries other than Singapore are losing population to emigration.

Government-sponsored birth control programs are unevenly distributed. Thailand’s low fertility rate of 1.6 children per adult woman was achieved in part via a government-sponsored condom campaign, and in part by rapid economic development, which made many couples feel that smaller families would be best. Also, as women gained more opportunities to work and study outside the home, they decided to have fewer children. High literacy rates for both men and women, along with Buddhist attitudes that accept the use of contraception, have also been credited for the decline in Thailand’s fertility rate.

The poorest and most rural countries in the region show the usual correlation between poverty, high fertility, and infant mortality. Timor-Leste, which suffered a violent, impoverishing civil disturbance before it gained independence from Indonesia, is still characterized by poverty, high fertility and high infant mortality (64 per 1000 live births). However, its oil resources promise to bring prosperity, if they are used to help the welfare of the entire population. If that happens, both fertility and infant mortality can be expected to fall. In Cambodia and Laos, fertility rates average 3.0 and 3.9 children, respectively. Infant mortality rates are 58 per 1000 live births for both Cambodia and Laos. On the other hand, in Vietnam, where people are only slightly more prosperous and urbanized, the fertility rate (2.0 children per adult woman) and infant mortality rate (16 per 1000 births) are far lower. These lower rates are explained by the fact that as a socialist state, Vietnam provides basic education and health care—including birth control—to all, regardless of income. In Vietnam, literacy rates are more than 96 percent for men and 92 percent for women, whereas they are only 64 percent for women in Cambodia and in Laos. In addition, Vietnam’s rapidly developing economy is pulling in foreign investment, which provides more employment for women, and careers are replacing child rearing as the central focus of many women’s lives. Out of concern that these changes weren’t happening rapidly enough, and that a rapidly growing population would jeopardize Vietnam’s upswing in economic development, the government of Vietnam recently introduced a somewhat elastic two-child family policy. This policy has already brought on gender imbalance, as some couples are choosing abortion if the fetus is female.

The Philippines, which has a higher per capita income than Laos, Cambodia, Timor-Leste, or Vietnam, is an anomaly in population patterns, primarily because it is predominantly Roman Catholic (83 percent, see the Figure 10.26 map), a religion that officially does not allow birth control. Fertility there is among the highest in the region (3.2 per adult female); infant mortality is in the medium range (22 per 1000 live births); and maternal childbirth deaths are high despite female literacy rates being high (93 percent).

VIGNETTE

In Roman Catholic Philippines, Gina Judilla, who works outside the home, has had six children with her unemployed husband. They wanted only two, but because of the strong role of the Catholic Church and the political pressure it exerts, birth control was not available to them. Abortion is legal only to save the life of the mother, so with every succeeding pregnancy, she tried folk methods of inducing an abortion. None worked. Now she can afford to send only two of her six children to school.

A move by family planners to provide national reproductive health services and sex education is underway. A recent survey showed that 48 percent of all pregnancies in the Philippines in 2010 were unintended, which often led to “backstreet” abortions. Nonetheless, in 2011, only one-third of Philippine women had access to modern birth control methods; in 2005, because of pressure by conservative religious groups within the United States, the United States stopped offering birth control aid to the Philippines. [Source: Likhaan Center for Women’s Health, Inc. and the New York Times. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Population Pyramids

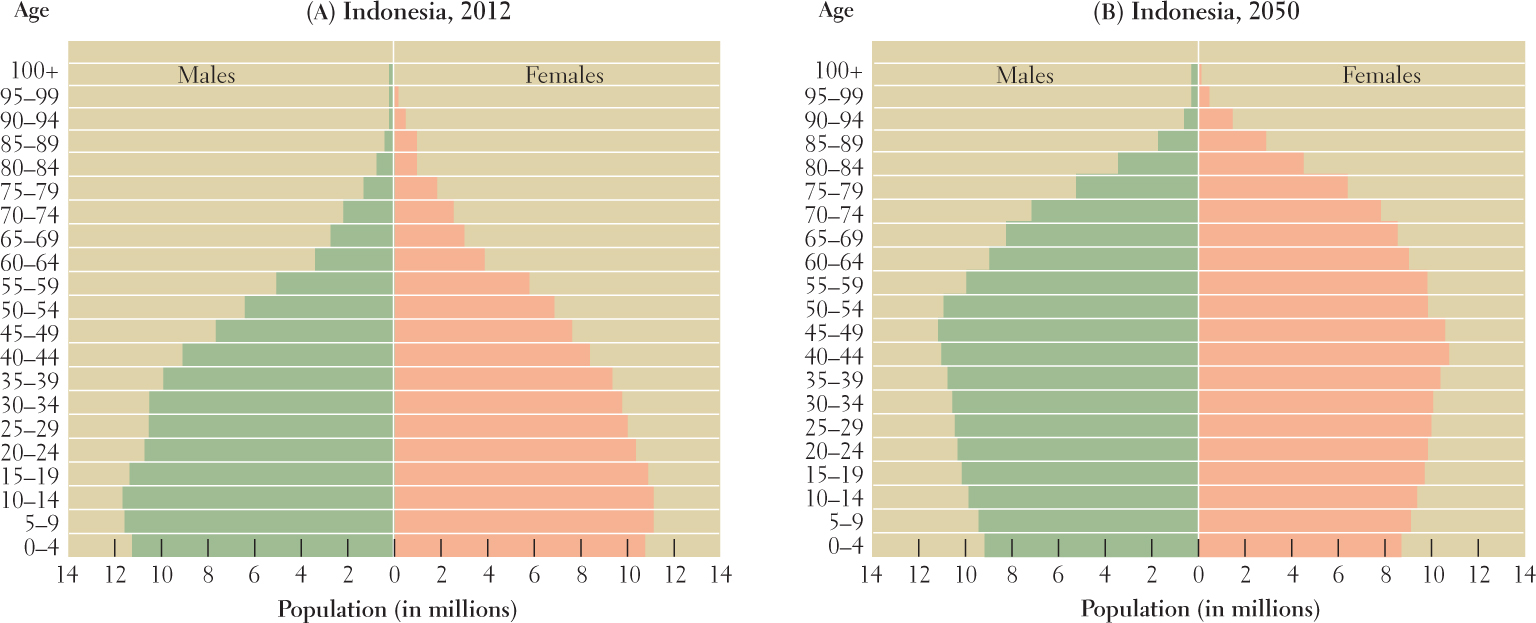

The youth and gender features of Southeast Asian populations are best appreciated by looking at the population pyramids for Indonesia. Figure 10.21 shows the 2012 population and the projected population for 2050. The wide bottom of the 2012 pyramid indicates that most people are age 30 and under, but the projections to 2050 show that eventually, with declining birth rates, those 30 and under will be outnumbered by those 35 and older. Indonesia will accumulate ever-larger numbers in the upper age groups, and the pyramid will eventually be more box-shaped, as those for Europe are now. The gender disparities (more males than females) that have developed over the last 20 years can be seen by carefully examining the lengths of the bars on the male and female sides of the pyramid for those age 15–19 and under. The difference is slight but significant because there is a rather consistent deficit of females; apparently they were selected out before birth, as is the case in Vietnam.

Southeast Asia’s Encounter with HIV-AIDS

As in sub-Saharan Africa (see Chapter 7), HIV-AIDS is a significant public health issue in Southeast Asia, although infection and death rates are now declining across the region. Cambodia, Thailand, and Burma currently have the highest infection rates. In Thailand in 2001, AIDS was the leading cause of death, overtaking stroke, heart disease, and cancer, but it is now just the third leading cause of death. Estimates are that about 500,000 Thais are infected, down from 1 million 12 years ago. Men between the ages of 20 and 40 have the highest rates of infection, but the rate of infection among women is rising. Thailand is one of the few countries that has been able to drastically reduce the incidence of HIV-AIDS; it did so through a well-funded program that increased the use of condoms, decreased STDs dramatically, and reduced visits to sex workers by half.

Elsewhere in the region, HIV rates are expected to increase rapidly in rural areas and in secondary cities where conservative religious leaders and faith-based international agencies (many from the United States) restrict sex education and AIDS-prevention programs, such as the promotion of condom use. Sex education is viewed as promoting promiscuity. At the same time, popular customs that support sexual experimentation (at least among men)—the high mobility of young adults, the reluctance of women to insist that their husbands and boyfriends use condoms, and intravenous drug use (primarily by men)—make aggressive prevention programs all the more essential. Also contributing to the spread of HIV among young women is sex tourism and sex-related human trafficking (discussed further).  233. ACTIVISTS: AIDS LINKED TO WOMEN’S RIGHTS ABUSES

233. ACTIVISTS: AIDS LINKED TO WOMEN’S RIGHTS ABUSES

Geographic Patterns of Human Well-Being

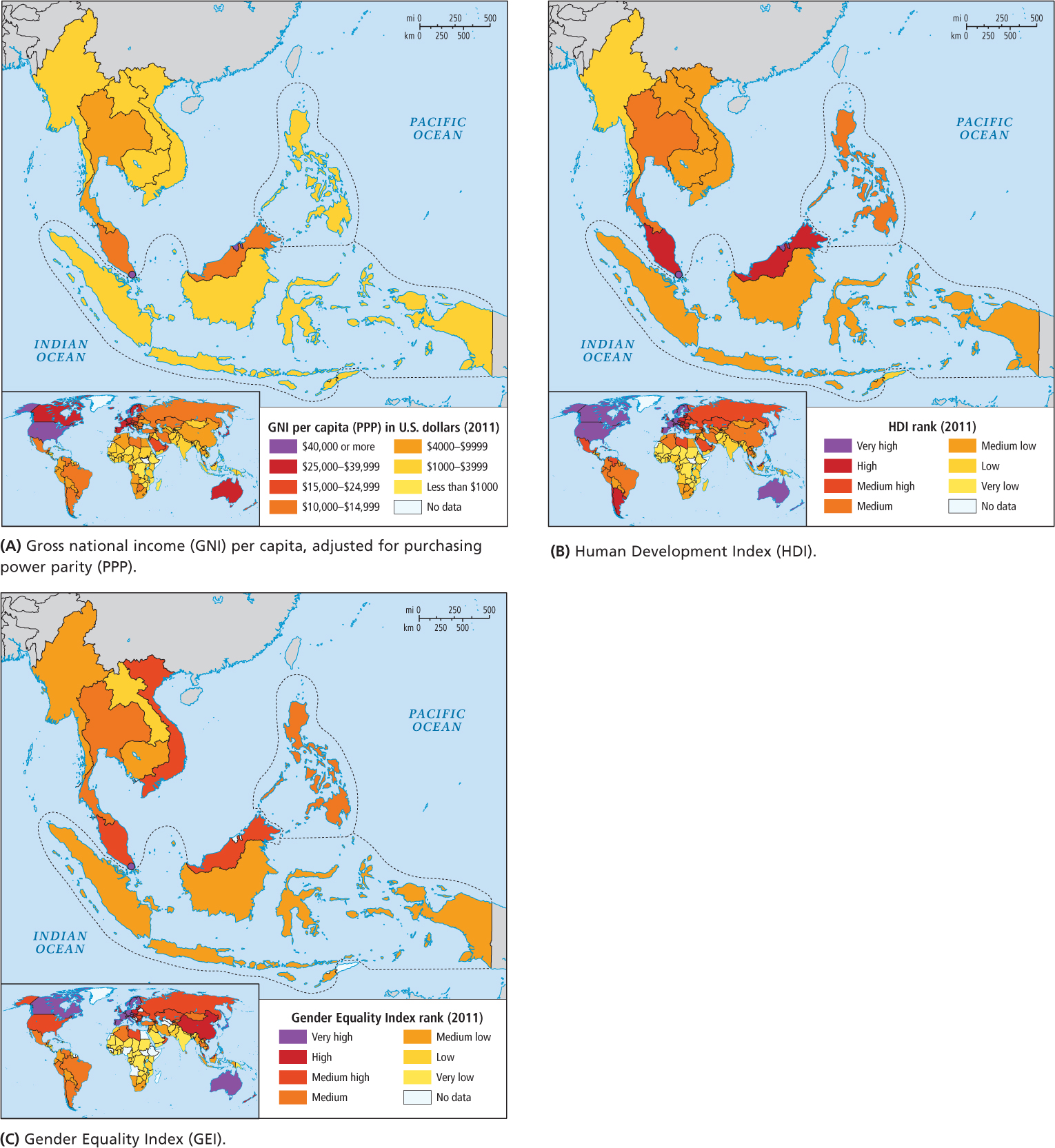

If human well-being is defined as the ability to enjoy long, healthy, and creative lives, as suggested by Mahbub ul Haq, the founder of the annual United Nations Human Development Report (UNHDR), then personal income statistics are not be the best way to measure success. Nonetheless, income is relevant to well-being, as evidenced by this series of three maps of Southeast Asia. Figure 10.22A shows gross national income (GNI) per capita (PPP) by country; Figure 10.22B shows each country’s rank on the Human Development Index (HDI); and Figure 10.22C depicts gender equality.

As shown in Figure 10.22A, two small countries, Singapore and Brunei, are the only places where annual per capita GNI (PPP) is in the highest category. For both countries, GNI (PPP) is about U.S.$50,000, which is a bit higher than in the United States and Australia and comparable to that in the richest countries in Europe (see the inset map of the world). Elsewhere in the region, per capita GNI (PPP) is considerably lower, with Malaysia the only country in the next highest range, at U.S.$13,710. Thailand is near the top of the medium range; and below it are Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Laos, and Cambodia, with per capita GNI (PPP) rates that vary from U.S.$1820 to U.S.$4730. In the Philippines, GNI (PPP) fell in recent years because the global recession cut the size of remittances and because of political troubles in the southern islands. In the lowest category are Timor-Leste and Burma.

Figure 10.22B shows each country’s rank on the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a calculation (based on adjusted real income, life expectancy, and educational attainment) of how adequately a country provides for the well-being of its citizens. Singapore and Brunei again do well at providing for the overall well-being of their citizens, as they rank in the two highest categories. Malaysia ranks high; Thailand and the Philippines rank medium; Indonesia, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia all rank medium low, while Burma ranks low. Many have lost rank over the last 5 years because of the global recession.

Figure 10.22C shows how well countries are ensuring gender equality in three categories: reproductive health, political and education empowerment, and access to the labor market. The countries with rankings closest to 1 have the highest degree of gender equality. As might be expected, Singapore ranks very high, at eighth in the world, but there are no data for Brunei, which ranks high in income and well-being. Malaysia ranks medium high; and Vietnam, which ranks low on income and well-being, ranks medium high in this category, perhaps because of residual benefits of the general communist (socialist) philosophy regarding gender equality. The remaining countries rank medium low to low.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

While population growth rates have slowed across the region, they are slowing the most in the developed economies of Singapore, Brunei, and Thailand.

While population growth rates have slowed across the region, they are slowing the most in the developed economies of Singapore, Brunei, and Thailand. The variations in population growth are linked to relative prosperity, gender roles, and availability of birth control.

The variations in population growth are linked to relative prosperity, gender roles, and availability of birth control. By 2050, some if not all countries in this region will have to address the issue of having an aging population.

By 2050, some if not all countries in this region will have to address the issue of having an aging population. Geographic Insight 4Population and Gender Even though countries in the region are far from having gender equity, population patterns are changing as job and educational opportunities for women improve and birth control is more widely available. Empowerment of women is increasing awareness that sex trafficking is an abuse of their human rights.

Geographic Insight 4Population and Gender Even though countries in the region are far from having gender equity, population patterns are changing as job and educational opportunities for women improve and birth control is more widely available. Empowerment of women is increasing awareness that sex trafficking is an abuse of their human rights. HIV-AIDS is a threat, to varying degrees, throughout the region. Preventative measures have proven quite successful in Thailand.

HIV-AIDS is a threat, to varying degrees, throughout the region. Preventative measures have proven quite successful in Thailand. Human well-being varies from very high (Singapore) to low (Timor-Leste, Burma, Laos, and Cambodia), with most countries ranking in the medium categories.

Human well-being varies from very high (Singapore) to low (Timor-Leste, Burma, Laos, and Cambodia), with most countries ranking in the medium categories.

Urbanization

Geographic Insight 5

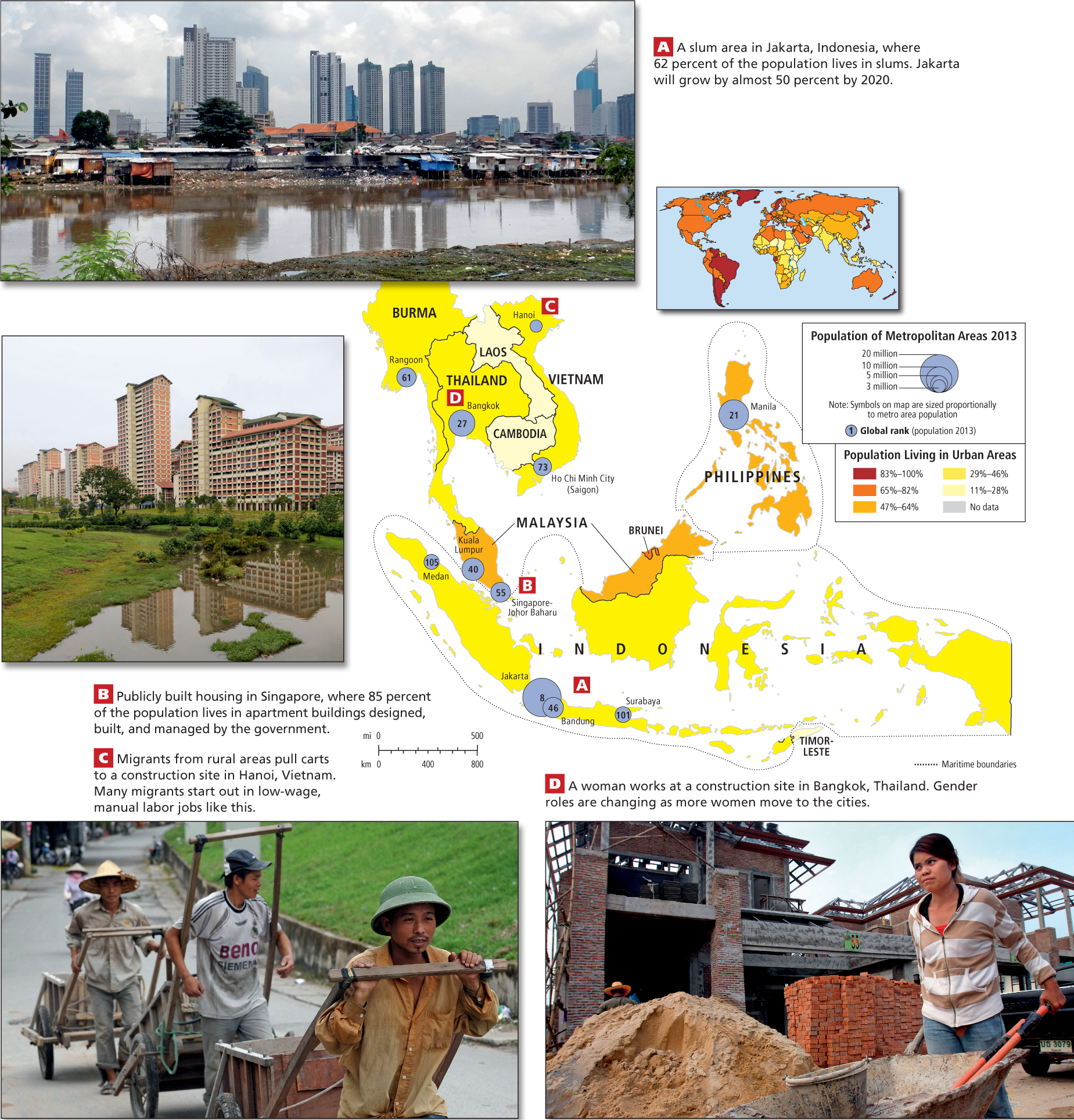

Urbanization, Food, and Development: The development of export-oriented modernized agriculture and agribusiness have forced farmers who were once able to produce enough food for their families to migrate to cities, where jobs that fit their skills are scarce, where they must purchase their food, and where the only affordable housing is in slums that lack essential services. Surplus skilled and semiskilled workers, especially women, often migrate abroad for employment.

Southeast Asia as a whole is only 42 percent urban, but the rural–urban balance is shifting steadily in response to declining agricultural employment and booming urban industries. The forces driving farmers into the cities are called the push factors in rural-to-urban migration. They include the rising cost of farming related to the use of new technologies and competition with agribusiness. Pull factors, in contrast, are those that attract people to the city, such as abundant manufacturing jobs and education opportunities. In Southeast Asia, as in all other regions, these factors have come together to create steadily increasing urbanization. Malaysia is already 64 percent urban; the Philippines, 63 percent; Brunei, 72 percent; and Singapore, 100 percent.

Throughout Southeast Asia, employment in agriculture has been declining since new production methods were introduced that increase the use of labor-saving equipment and reduce the need for human labor. Meanwhile, chemical pesticide and fertilizer use has also grown. While such additives can increase harvests dramatically and increase the supply of food to cities, they also drive the cost of production higher than what most farmers can afford. Many family farmers have sold their land to more prosperous local farmers or to agribusiness corporations and moved to the cities. These people, skilled at traditional farming but with little formal education, often end up in the most menial of urban jobs (Figure 10.23C) and live in circumstances that do not allow them to grow their own food (see Figure 10.23A).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in Southeast Asia, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Why might these people be living on water in Jakarta?

Why might these people be living on water in Jakarta?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

If government-built apartment buildings in Singapore are intended for the middle class, what are the common facilities that house most of the illegal, noncitizen population?

If government-built apartment buildings in Singapore are intended for the middle class, what are the common facilities that house most of the illegal, noncitizen population?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What about this photo suggests that these men may be of rural origins?

What about this photo suggests that these men may be of rural origins?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why might this photo be viewed as a triumph for women's rights in Bangkok?

Why might this photo be viewed as a triumph for women's rights in Bangkok?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Labor-intensive manufacturing industries (garment and shoe making, for instance) are expanding in the cities and towns of the poorer countries, such as Cambodia, Vietnam, and parts of Indonesia and Timor-Leste. In the urban and suburban areas of the wealthier countries—Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and parts of Indonesia and the northern Philippines—technologically sophisticated manufacturing industries are also growing. These include automobile assembly, chemical and petroleum refining, and computer and other electronic equipment assembly. Riding on this growth in manufacturing are innumerable construction projects that often provide employment to recent migrants (see Figure 10.23C, D).

Cities like Jakarta, Manila, and Bangkok, among the most rapidly growing metropolitan areas in the world, are primate cities—cities that, with their suburbs, are vastly larger than all others in a country. Bangkok is more than 20 times larger than Thailand’s next-largest metropolitan area, Udon Thani; and Manila is more than 10 times larger than Davao, the second-largest city in the Philippines. Thanks to their strong industrial base, political power, and the massive immigration they attract, primate cities can dominate whole countries; and in the case of Singapore, the city constitutes the entire country.

Rarely can such cities provide sufficient housing, water, sanitation, or even decent jobs for all the new rural-to-urban migrants. Many millions of urban residents in this region live in squalor, often on floating raft-villages on rivers and estuaries. Of all the cities in Southeast Asia, only Singapore provides well for nearly all of its citizens (see Figure 10.23B). Even there, however, a significant undocumented, noncitizen population lives in poverty on islands surrounding the city. The experience of rural-to-urban migrants who go to Bangkok or Jakarta is more typical; migrants there often live in slums on the banks of polluted, trash-ridden waterbodies (see Figure 10.23A).

Emigration Related to Globalization

foreign exchange foreign currency that countries need to purchase imports

The Merchant Marine

Skilled male seamen from Southeast Asia make up a significant portion of the international merchant marines, where conditions are considerably better than they are for most migrant workers. Nonetheless, in the merchant marines, it is customary for workers to be paid according to their homeland’s pay scales, which makes employing seamen from low-wage Southeast Asian countries attractive to shipowners. The seamen work aboard international freighters or on luxury cruise liners as deckhands, cooks, engine mechanics—and a few become officers. Generally, seamen work for 6 months at a time—with only a few hours a day for breaks—saving nearly every penny. At the end of a tour of duty, they return home to their families for another 6 months, where they often contribute financially to the well-being of an extended group of kin and friends and send their children to advanced education.

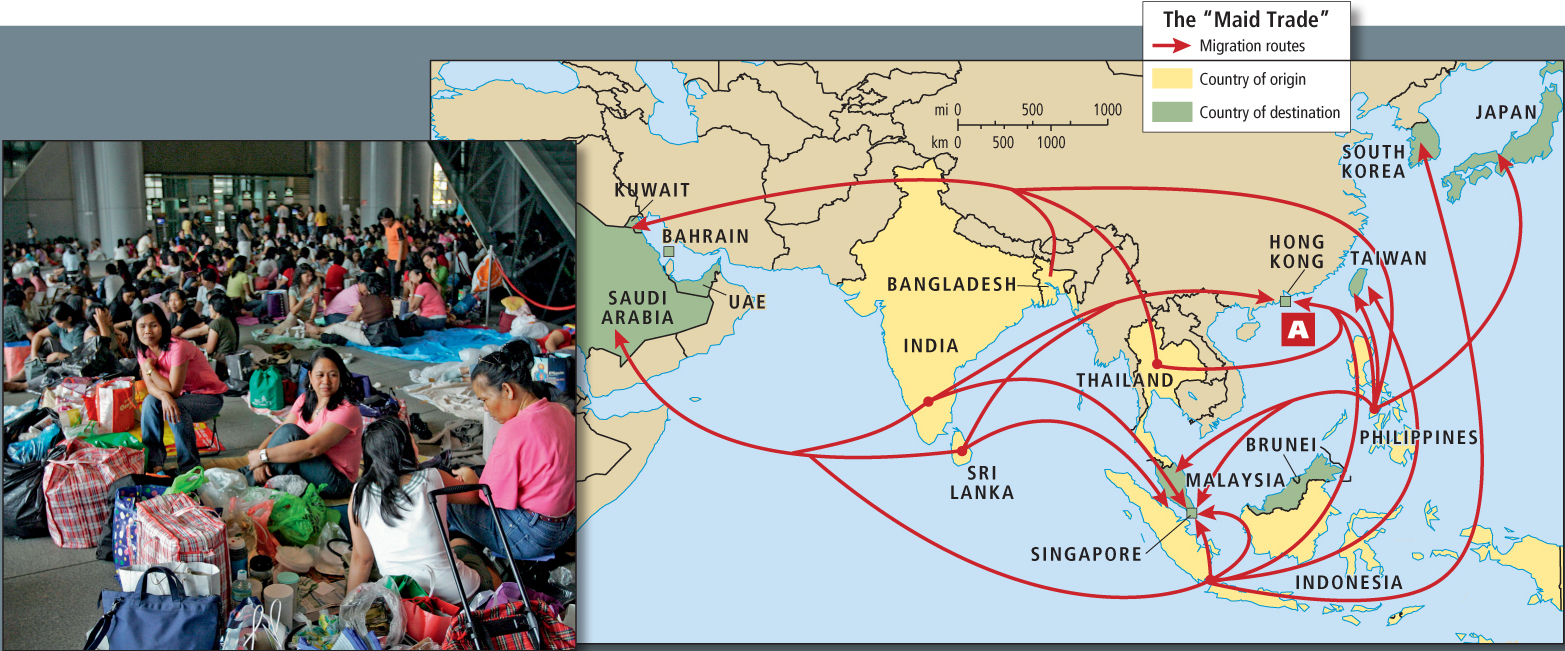

The Maid Trade

Women constitute well over 50 percent of the more than 8 million emigrants from Southeast Asia. Many skilled nurses and technicians from the Philippines work in European, North American, and Southwest Asian cities. About 3 million participate in the global “maid trade” (shown in Figure 10.24A and the figure map). Most are educated women from the Philippines and Indonesia who work under 2- to 4-year contracts in wealthy homes throughout Asia. An estimated 1 to 3 million Indonesian maids now work outside of the country, mostly in the Persian Gulf.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How does this photo portray the inventiveness of women in the maid trade?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The maid trade has become notorious for abusive working conditions and for having employers who often do not pay what they promise. In Saudi Arabia, the NGO Human Rights Watch is monitoring the cases of Muslim Indonesian women who were brutally abused—two were killed—by members of a privileged Saudi family. The Philippines went so far as to ban the maid trade in 1988, but reestablished it in 1995 after better pay and working conditions were negotiated with the countries that receive the workers.

VIGNETTE

Every Sunday is amah (nanny) day in Hong Kong. Gloria Cebu and her fellow Filipina maids and nannies stake out temporary geographic territory on the sidewalks and public spaces of the central business district (see Figure 10.24A). Informally arranging themselves according to the different dialects of Tagalog (the official language of the Philippines) they speak, they create room-like enclosures of cardboard boxes and straw mats where they share food, play cards, give massages, and do each other’s hair and nails. Gloria says it is the happiest time of her week, because for the other 6 days she works alone, caring for the children of two bankers.

Gloria, who is a trained law clerk, has a husband and two children back home in Manila. Because the economy of the Philippines has stagnated, she can earn more in Hong Kong as a nanny than in Manila in the legal profession. Every Sunday she sends most of her income (U.S.$125 a week) home to her family. [Sources: Kirsty Vincin and the Economist. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 5Urbanization, Food, and Development Rural-to-urban migration instigated by agricultural modernization and mechanization has led to overcrowded slums that lack basic services, where farmers who were once able to produce sufficient food for their families now must purchase food.

Geographic Insight 5Urbanization, Food, and Development Rural-to-urban migration instigated by agricultural modernization and mechanization has led to overcrowded slums that lack basic services, where farmers who were once able to produce sufficient food for their families now must purchase food. Southeast Asia as a whole is only 43 percent urban, but the rural–urban balance is shifting steadily.

Southeast Asia as a whole is only 43 percent urban, but the rural–urban balance is shifting steadily. Often the focus of migration is the capital of a country, which may become a primate city—a city that, with its suburbs, is vastly larger than all others in a country.

Often the focus of migration is the capital of a country, which may become a primate city—a city that, with its suburbs, is vastly larger than all others in a country. Thousands of people emigrate from the region each year to seek temporary or long-term employment in the Middle East, Europe, North America, Asian cities, or on the world ocean.

Thousands of people emigrate from the region each year to seek temporary or long-term employment in the Middle East, Europe, North America, Asian cities, or on the world ocean.

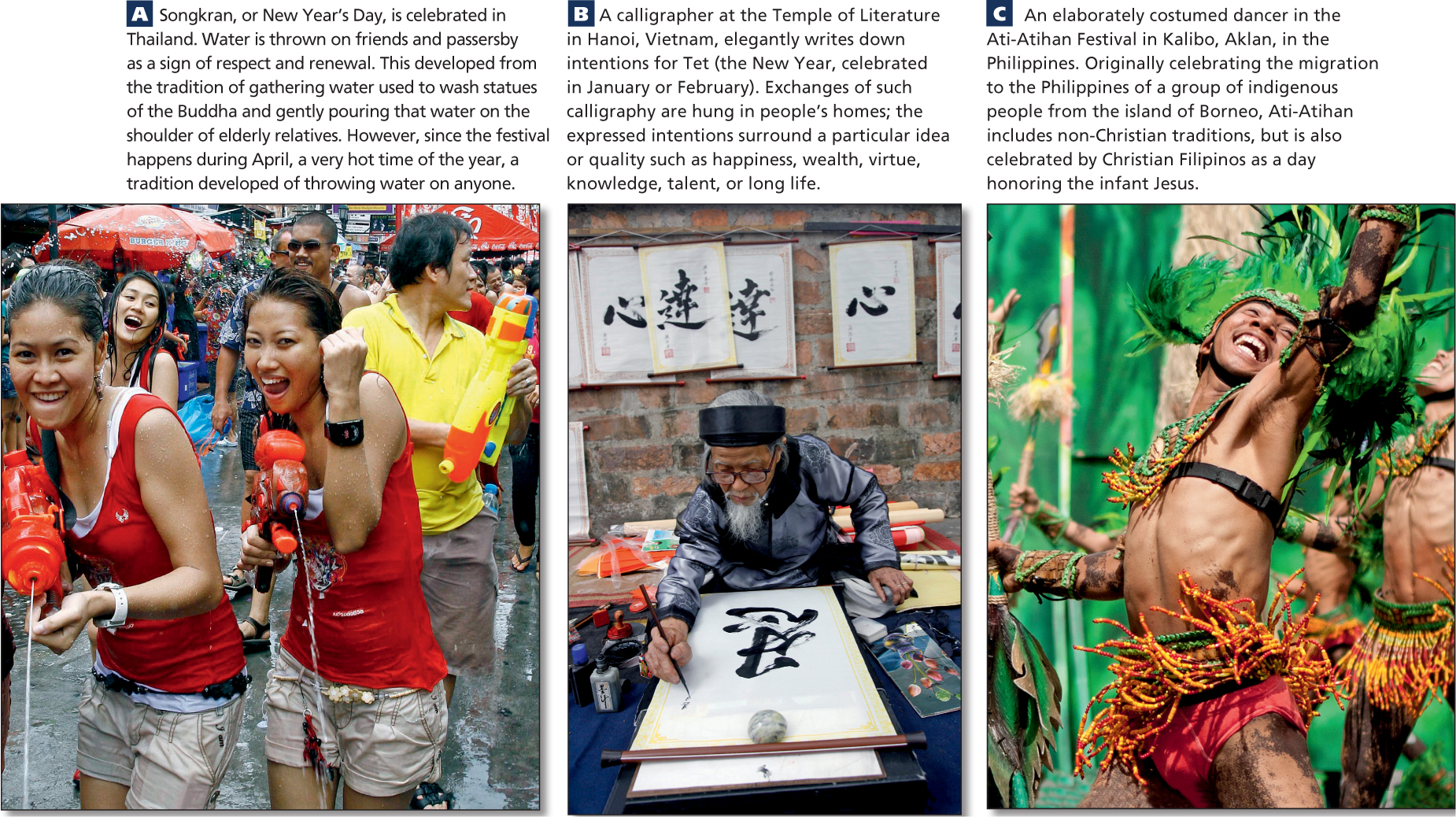

Cultural and Religious Pluralism

Southeast Asia is a place of cultural pluralism in that it is inhabited by groups of people from many different backgrounds. Over the past 40,000 years, migrants have come to the region from India, the Tibetan Plateau, the Himalayas, China, Southwest Asia, Japan, Korea, and the Pacific. Many of these groups have remained distinct, partly because they lived in isolated pockets separated by rugged topography or seas. However, the religious practices and traditions of many groups show diverse cultural influences (Figure 10.25).

cultural pluralism the cultural identity characteristic of a region where groups of people from many different backgrounds have lived together for a long time but have remained distinct

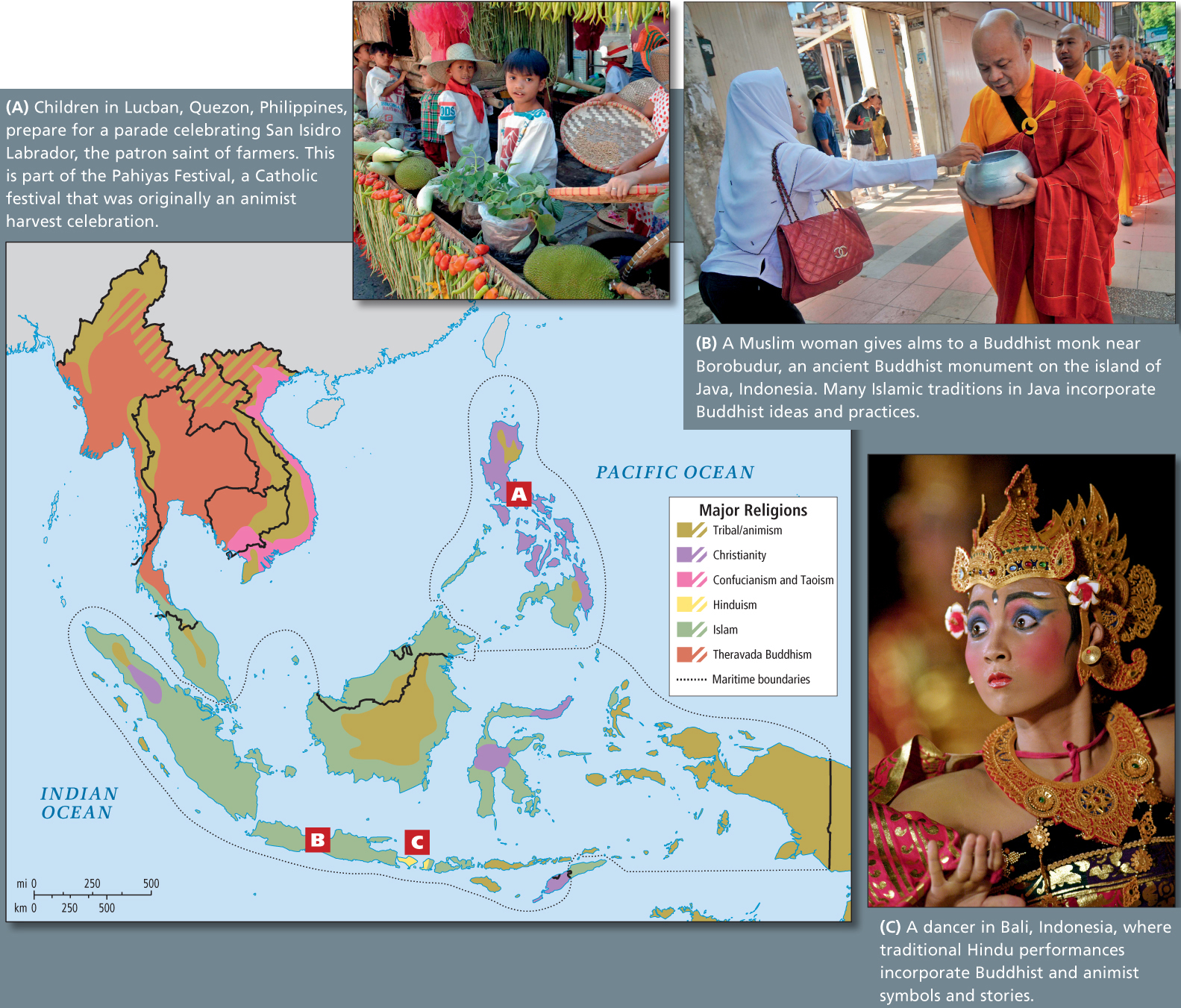

As discussed in the Religious Legacies section (page 551), the major religious traditions of Southeast Asia include Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity, and animism (Figure 10.26). In animism, a belief system common among many indigenous peoples, natural features such as trees, rivers, crop plants, and the rains all carry spiritual meaning. These natural phenomena are the focus of festivals and rituals to give thanks for bounty and to mark the passing of the seasons, and these ideas have permeated all the imported religious traditions of the region.

The patterns of religious practice are complex; the patterns of distribution reveal an island–mainland division. All but animism originated outside the region and were brought primarily by traders, priests (Brahmin and Christian), and colonists. Buddhism is dominant on the mainland, especially in Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia. In Vietnam, people practice a mix of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism that originated in China. Islam is dominant in Indonesia (the world’s largest Muslim country), on the southern Malay Peninsula, and in Malaysia, and it is increasing in popularity in the southern Philippines. Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion in Timor-Leste and the Philippines, where it was introduced by Portuguese and Spanish colonists, respectively. Hinduism first arrived with Indian traders thousands of years ago and was once much more widespread; now it is found only in small patches, chiefly on the islands of Bali and Lombok, east of Java. Recent Indian immigrants who came as laborers in the twentieth century (during the latter part of the European colonial period) have reintroduced Hinduism to Burma, Malaysia, and Singapore, but only as minority communities.

All of Southeast Asia’s religions have changed as a result of exposure to one another. Many Muslims and Christians believe in spirits and practice rituals that have their roots in animism. Hindus and Christians in Indonesia, surrounded as they are by Muslims, have absorbed ideas from Islam, such as the seclusion of women. Muslims have absorbed ideas and customs from indigenous belief systems, especially ideas about kinship and marriage, as illustrated in the following vignette.

VIGNETTE

Although arranged marriages have historically been the norm across Southeast Asia, in most urban and rural areas now, marriages are love matches. Such is the case for Harum and Adinda, who live in Tegal, on the island of Java in Indonesia. They met in high school and some 10 years later, after saving a considerable sum of money, decided to formally ask both sets of parents if they could marry. Harum, an accountant, would normally be expected to pay the wedding costs, which could run to many thousands of dollars; however, Adinda was able to contribute from her salary as a teacher. Like nearly all Javanese people, both are Muslim. Because Islam does not have elaborate marriage ceremonies, colorful rituals from Christianity, Buddhism, and indigenous animism will enhance the elaborate and festive occasion.

In preparation, both bride and groom participate in unique Javanese rituals that remain from the days when marriages were arranged and the bride and groom did not know each other (Figure 10.27). A pemaes, a woman who prepares a bride for her wedding and whose role is to inject mystery and romance into the marriage relationship, bathes and perfumes the bride. She also puts on the bride’s makeup and dresses her, all the while making offerings to the spirits of the bride’s ancestors and counseling her about how to behave as a wife and how to avoid being dominated by her husband. The groom also takes part in ceremonies meant to prepare him for marriage. Both are counseled that their relationship is bound to change over the course of the decades as they mature and as their family grows older.

Despite the elaborate preparations for marriage, divorce in Indonesia (and also in Malaysia) is fairly common among Muslims, who often go through one or two marriages early in life before they settle into a stable relationship. Although the prevalence of divorce is lamented by society, it is not considered outrageous or disgraceful. Apparently, ancient indigenous customs predating Islam allowed for mating flexibility early in life, and this attitude is still tacitly accepted. [Source: Jennifer W. Nourse and Walter Williams. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Globalization Brings Cultural Diversity and Homogeneity

Southeast Asia’s cities are extraordinarily culturally diverse, a fact that is illustrated by their food customs (Figure 10.28). But in some ways, this diversity decreases as the many groups continue to be exposed to each other and to global culture. For example, Malaysian teens of many different ethnicities (Chinese, Tamil, Malay, Bangladeshi) spend much of their spare time following the same European soccer teams, playing the same video games, visiting the same shopping centers, eating the same fast food, and talking to each other in English. While rural areas retain more traditional influences—of the world’s 6000 or so actively spoken languages, 1000 can be found in rural Southeast Asia—in cities, one main language usually dominates trade and politics.

One group that has brought cultural diversity to Southeast Asia is the Overseas (or ethnic) Chinese (see Chapter 9, pages 514–515). Small groups of traders from southern and coastal China have been active in Southeast Asia for thousands of years; over the centuries, there has been a constant trickle of immigrants from China. The forbearers of most of today’s Overseas Chinese, however, began to arrive in large numbers during the nineteenth century, when the European colonizers needed labor for their plantations and mines. Later, those who fled China’s Communist Revolution after 1949 sought permanent homes in Southeast Asian trading centers. Today, more than 26 million Overseas Chinese live and work across Southeast Asia as shopkeepers and as small business owners. A few are wealthy financiers, and a significant number are still engaged in agricultural labor.

Chinese success at small-scale commercial and business activity throughout the region has reinforced the perception that the Chinese are diligent, clever, and extremely frugal, often working very long hours. Although few are actually wealthy, with their region-wide family and friendship connections and access to start-up money, some have been well positioned to take advantage of the new growth sectors in the globalizing economies of the region. Sometimes externally funded, new Chinese-owned enterprises have put out of business older, more traditional establishments depended upon by local people of modest incomes (both ethnic Malay and ethnic Chinese).

In recent years, when low- and middle-income Southeast Asians were hurt by the recurring financial crises, some tended to blame their problems on the Overseas Chinese. Waves of violence resulted. Chinese people were assaulted, their temples desecrated, and their homes and businesses destroyed. Conflicts involving the Overseas Chinese have taken place in Vietnam, Malaysia, and in many parts of Indonesia (Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi), as well. Some Overseas Chinese have attempted to diffuse tensions through public education about Chinese culture. Others have shown their civic awareness by financing economic and social aid projects to help their poorer neighbors, usually of local ethnic origins (Malay, Thai, Indonesian).

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Embracing Unity Within Diversity

For the most part, cultural diversity in Southeast Asia has led to amicable relations across ethnic and religious lines. Some countries actively promote national unity policies (e.g., Pancasila in Indonesia) as an antidote to diversity.

Gender Patterns in Southeast Asia

As observed in the Population Patterns section, gender roles are being transformed across Southeast Asia by urbanization and the changes it brings to family organization and employment. Here we look at some surprising traditional patterns of gender roles in extended families. However, moving to the city shifts people away from extended families and toward the nuclear family. The gains that women have made in political empowerment, educational achievement, and paid employment have not erased gender disparities.

Family Organization, Traditional and Modern

Throughout the region, it has been common for a newly married couple to reside with, or close to, the wife’s parents. Along with this custom is a range of behavioral rules that empower the woman in a marriage, despite some basic patriarchal attitudes. For example, a family is headed by the oldest living male, usually the wife’s father. When he dies, he passes on his wealth and power to the husband of his oldest daughter, not to his own son. (A son goes to live with his wife’s parents and inherits from them.) Hence, a husband may live for many years as a subordinate in his father-in-law’s home. Instead of the wife being the outsider, subject to the demands of her mother-in-law—as is the case, for example, in South Asia—it is the husband who must show deference. The inevitable tension between the wife’s father and the son-in-law is resolved by the custom of ritual avoidance—in daily life they simply arrange to not encounter each other much. The wife manages communication between the two men by passing messages and even money back and forth. Consequently, she has access to a wealth of information crucial to the family and has the opportunity to influence each of the two men.

Another traditional custom that empowers women is that women are often the family financial managers. Husbands turn over their pay to their wives, who then apportion the money to various household and family needs.

Urbanization and the shift to the nuclear family mean that young couples now frequently live apart from the extended family, an arrangement that takes the pressure to defer to his father-in-law off the husband. Because this nuclear family unit is often dependent entirely on itself for support, wives usually work for wages outside the home. Although married women lose the power they would have if they lived among their close kin, they are empowered by the opportunity to have a career and an income. The main drawback of this compact family structure, as many young families have discovered in Europe and the United States, is that there is no pool of relatives available to help working parents with child care and housework. Further, no one is left to help elderly parents maintain the rural family home.

Political and Economic Empowerment of Women

Women have made some impressive gains in politics in Southeast Asia. Economically, they still earn less money than men and work less outside the home, but this will likely change if their level of education in relation to that of men continues to increase.

Southeast Asia has had several prominent female leaders over the years, most of whom have risen to power in times of crisis as the leaders of movements opposing corrupt or undemocratic regimes. In the Philippines, Corazon Aquino, a member of a large and powerful family, became president in 1986 after leading the opposition to Ferdinand Marcos, whose 21-year presidency was infamous for its corruption and authoritarianism. She is credited with helping reinvigorate political freedoms in the Philippines. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, from another powerful family, became president in 2001 after opposing a similarly corrupt president, and then she was accused of corruption herself. Still, her administration kept the economy sound throughout the global recession starting in 2007. In 2010, Benigno Aquino III, son of Corazon, became president.

In Indonesia, Megawati Sukarnoputri became president in 2001 after decades of leading the opposition to Suharto’s notoriously corrupt 31-year reign. And in Burma, for more than two decades, a woman, Aung San Suu Kyi, has led opposition to the military dictatorship.

All of these women leaders were wives or daughters of powerful male political leaders, which raises some questions of nepotism. However, family favoritism cannot account for the several countries where the percentage of female national legislators is well above the world average of 18 percent: Timor-Leste (29 percent), Laos (25 percent), Vietnam (24 percent), Singapore (22 percent), the Philippines (22 percent), and Cambodia (21 percent).

Despite their increasing successes in politics and their acknowledged role in managing family money, women still lag well behind men in terms of economic empowerment (see Figure 10.22C). Throughout the region, men have a higher rate of employment outside the home than women and are paid more for doing the same work. But changes may be on the way. In Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, significantly more women than men are completing training beyond secondary school. If training qualifications were the sole consideration for employment, women would appear to have an advantage over men. This advantage may be significant if service sector economies, which generally require more education, become dominant in more countries. The service economy already dominates in Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia.

Globalization and Gender: The Sex Industry

sex tourism the sexual entertainment industry that serves primarily men who travel for the purpose of living out their fantasies during a few weeks of vacation

One result of the “success” of sex tourism is a high demand for sex workers, and this demand has attracted organized crime. Estimates of the numbers of sex workers vary from 30,000 to more than a million in Thailand alone. Once girls and women have been first forced into the trade, gangs often coerce them into remaining in sex work. Demographers estimate that 20,000 to 30,000 Burmese girls taken against their will—some as young as 12—are working in Thai brothels. Their wages are too low to enable them to buy their own freedom. In the course of their work, they must service more than 10 clients per day, and they are routinely exposed to physical abuse and sexually transmitted diseases, especially HIV.

VIGNETTE

Twenty-five-year-old Watsanah K. (not her real name) awakens at 11:00 every morning, attends afternoon classes in English and secretarial skills, and then goes to work at 4:00 p.m. in a bar in Patpong, Bangkok’s red light district. There she will meet men from Europe, North America, Japan, Taiwan, Australia, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere, who will pay to have sex with her. She leaves work at about 2:00 a.m., studies for a while, and then goes to sleep.

Watsanah was born in northern Thailand to an ethnic minority group who are poor subsistence farmers. She married at 15 and had two children shortly thereafter. Several years later, her husband developed an opium addiction. She divorced him and left for Bangkok with her children. There, she found work at a factory that produced seat belts for a nearby automobile plant. In 1997, Watsanah lost her job as the result of the economic crisis that ripped through Southeast Asia. To feed her children, she became a sex worker.

Although the pay, between U.S.$400 and U.S.$800 a month, is much better than the U.S.$100 a month she earned in the factory, the work is dangerous and demeaning. Sex work, though widely practiced and generally accepted in Thailand, is illegal, and the women who do it are looked down on. As a result, Watsanah must live in constant fear of going to jail and losing her children. Moreover, she cannot always make her clients use condoms, which puts her at high risk of contracting AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. “I don’t want my children to grow up and learn that their mother is a prostitute,” says Watsanah. “That’s why I am studying. Maybe by the time they are old enough to know, I will have a respectable job.” [Source: Alex Pulsipher and Debbi Hempel; Kaiser Family Foundation; BBC News. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Women’s Improving Status in Southeast Asia

Building on strong traditional roles at the family level, women now occupy prominent political roles in many countries, and their rising educational levels suggest that even in the most conservative countries, changes in gender roles will be significant. One result of the rising political status of women is that there is more focus on the abuse of women and girls in the sex industry.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The major religious traditions of Southeast Asia include Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity, and animism. All originated outside the region, with the exception of the animist belief systems.

The major religious traditions of Southeast Asia include Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity, and animism. All originated outside the region, with the exception of the animist belief systems. In some areas, women’s economic and political empowerment builds on cultural traditions that give special responsibilities to women.

In some areas, women’s economic and political empowerment builds on cultural traditions that give special responsibilities to women. Some countries have become centers for the global sex industry, which puts many women at risk of violence and disease.

Some countries have become centers for the global sex industry, which puts many women at risk of violence and disease.