11.1 11 Oceania: Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific

11.1.1 Geographic Insights: Oceania

Geographic Insights: Oceania

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Climate Change and Water: Oceania’s sea level and freshwater resources are being impacted by climate change.

2. Food and Development: European systems for producing food and fiber introduced into Oceania have greatly changed environments.

3. Globalization and Development: Globalization, coupled with a greater focus on neighboring Asia (rather than on long-time connections with Europe), has transformed patterns of trade and economic development across Oceania.

4. Population and Urbanization: This largest region of the world is only lightly populated, but it is highly urbanized.

5. Gender, Power, and Politics: Changes in political empowerment have taken different forms across Oceania, but there is a general trend toward a more active role for women.

The Oceanian Region

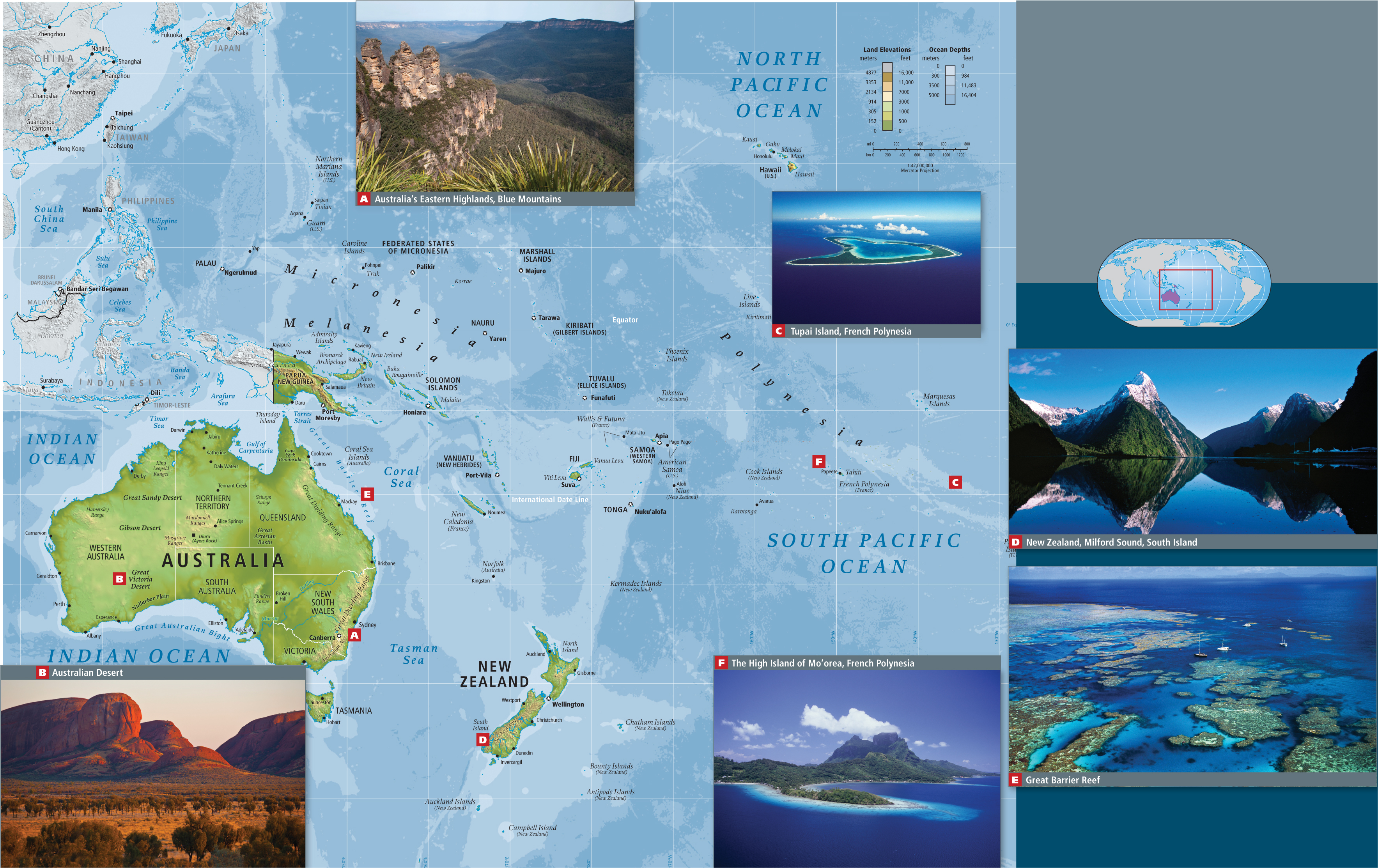

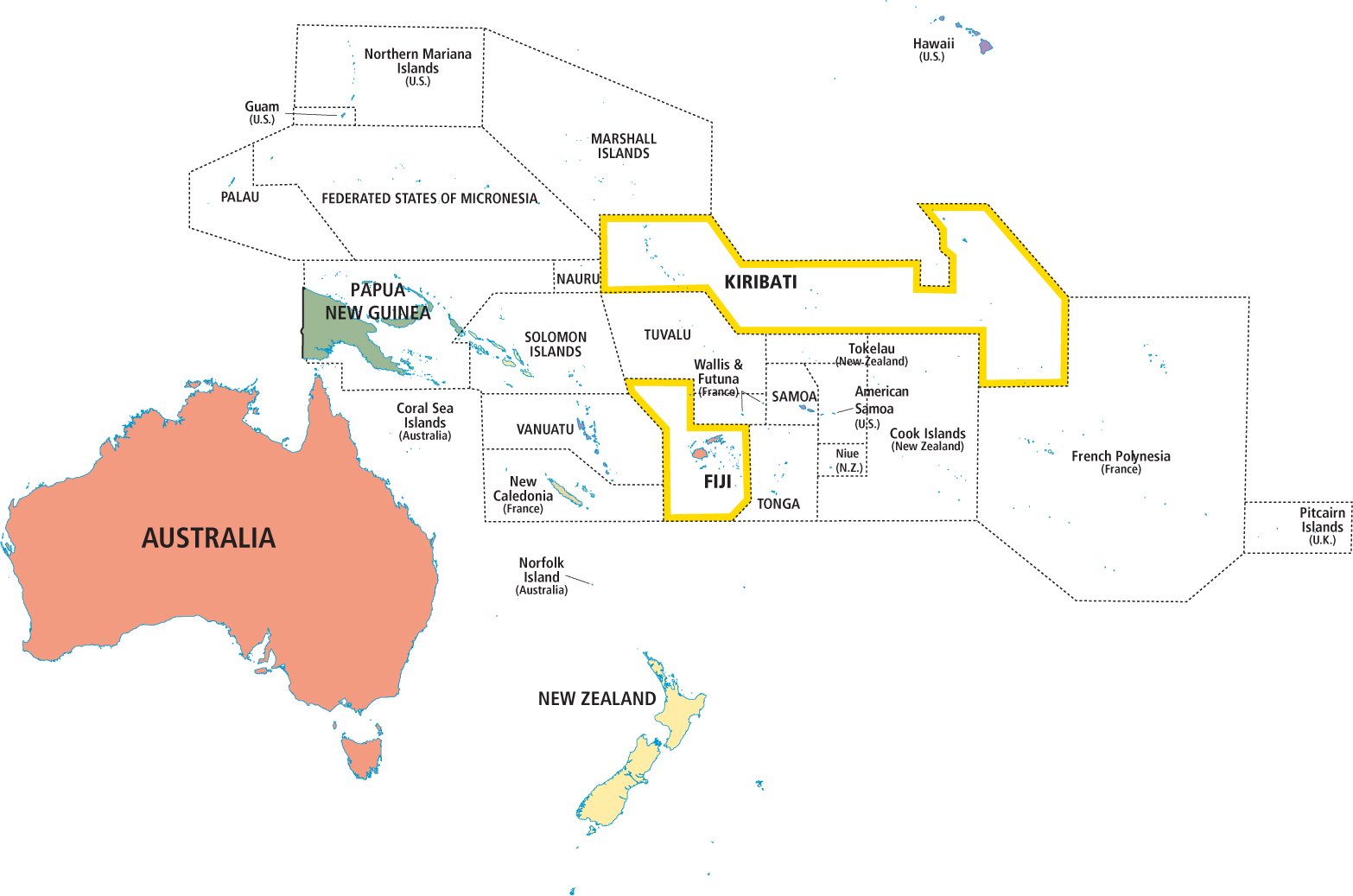

Oceania (see Figure 11.1; see also Figure 11.3) is the largest but least populated world region. The idyllic, far-flung landscapes of the Pacific disguise the fact that the people of this region face particularly complex challenges. The nine thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights on this page. Vignettes, like the one that follows about the Kiribati archipelago and the challenges its people face due to climate change and rising seas, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

Aurora (a pseudonym) is a nursing student in Brisbane, Australia, who is undergoing a wrenching personal adaptation due to climate change. Aurora is from Kiribati, a Pacific nation of 33 tiny islands barely 6½ feet above sea level. Rising seas are swamping the Kiribati archipelago, which straddles the equator just west of the international date line (180° longitude). Aurora pines for her island’s blue lagoons. While she studies for a new future and prepares to become her household’s primary income earner, she does so without the daily close company of her raucous extended family.

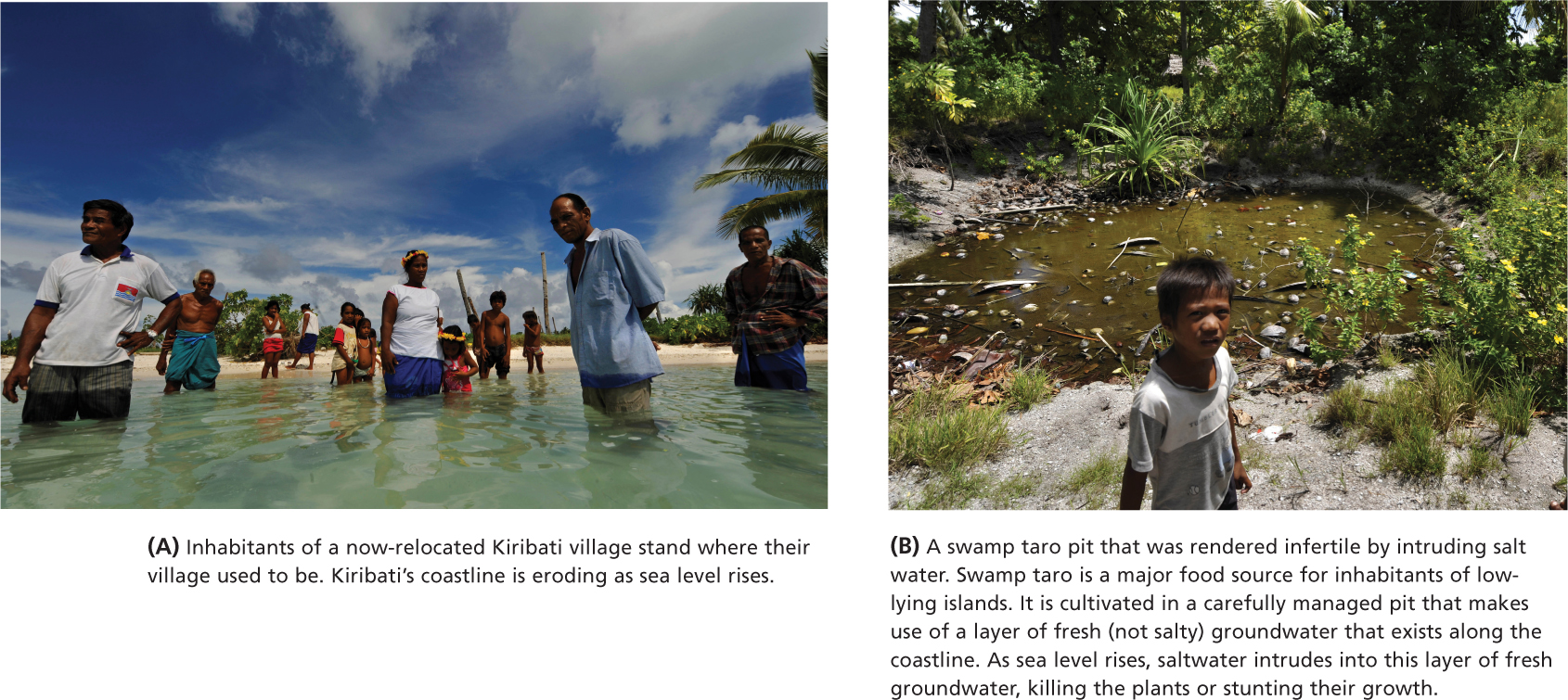

Several years ago, Aurora and her fellow citizens (100,000 people live in Kiribati) began to notice alarming environmental changes (Figure 11.2). Their drinking water was getting brackish (salty), several shoreline villages had sunk below sea level, and the climate became so dry that skilled gardeners could no longer raise their customary cabbages, taro crops, and cucumbers. Drought conditions were worsened by rising salty tides that saturated formerly fertile soil (see Figure 11.2A, B). Scientists predict that in a few decades, with rising seas and more frequent droughts and storms, much of Kiribati will be uninhabitable.

Aurora’s nursing education, funded by a government program called AusAID, is one of several strategies developed by Kiribati president Anote Tong to encourage his people to gradually “migrate with dignity.” President Tong sees climate change as a huge challenge for his country, and he hopes that other South Pacific islands, as well as Australia and New Zealand, will allow Kiribati people to resettle there permanently. Through the AusAID program, Aurora and other young people receive an education that will help them support their large extended families after they have found employment outside Kiribati and their family members have joined them.

But it is a tough transition. Another nursing student says he feels like he is losing his identity as his nation sinks into the sea. Some students’ parents refuse to leave Kiribati. They see the changes in sea level and rainfall, but as Christians they believe that “God is not so silly to allow people to perish just like that.”

In March 2012, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) reported that President Tong had approached landowners on the island nation of Fiji, 1300 miles to the south (Figure 11.3), hoping to buy Fijian land. His goals are twofold: to produce food to export to Kiribati and to import Fijian soil to replace the soil lost to sea level rise in Kiribati. This proposition will surely trigger controversy in Fiji, which is already experiencing social and political problems (see pages 617–619). [Sources: National Public Radio; BBC News Asia. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Perhaps nowhere else on Earth are the effects of climate change so measurably real as they are in the low-lying islands of the Pacific, where changes in rainfall patterns and sea level are not abstractions. Of special note is the fact that these islands have contributed little to the greenhouse gases that have triggered rapid climate change—not so much because of the low-emission lifestyles of the islands’ inhabitants, but rather because the islands’ total population is small. As we shall see, seemingly remote Pacific places are anything but remote from general global influences. Beyond climate change, people in this region are dealing with changes brought on by tourism, environmental degradation caused by modern mining techniques, freshwater scarcity, ocean pollution, and rapidly changing cultural and trading patterns.