Physical Patterns

The Pacific Ocean serves as both a link and a barrier in Oceania. Plants and animals have found their way from island to island by floating on the water, swimming, or flying; humans have long used the ocean as a way to make contact with other peoples for visiting, trading, and raiding. The movement of the water in the Pacific, with its varying temperatures, influences climates across all the landmasses of the Pacific Rim. Unfortunately, as we shall see, the ocean also serves as a conveyer of pollution, especially discarded plastics.

The wide expanses of water also serve as a barrier, profoundly limiting the natural diffusion of plant and animal species and keeping Pacific Islanders spatially isolated from one another. The vast ocean has imposed solitude and fostered self-sufficiency and subsistence economies among its human occupants well into the modern era.

Continent Formation

Gondwana the great landmass that formed the southern part of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea

Australia is shaped roughly like a dinner plate with an irregularly broken rim with two bites taken out of it: one in the north (the Gulf of Carpentaria) and one in the south (the Great Australian Bight). The center of the plate is the great lowland Australian desert, with only two hilly zones and rocky outcroppings (see Figure 11.1B). The eastern rim of Australia is composed of uplands; the highest and most complex of these are the long, curving Eastern Highlands (labeled “Great Dividing Range” in Figure 11.1; see also Figure 11.1A). Over millennia, the forces of erosion—both wind and water—have worn most of Australia’s landforms into low, rounded formations. Some of these, like Uluru (Ayers Rock), are quite spectacular (Figure 11.4).

Great Barrier Reef the longest coral reef in the world, located off the northeastern coast of Australia

Island Formation

The islands of the Pacific were (and are still being) created by a variety of processes related to the movement of tectonic plates. The islands found in the western reaches of Oceania—including New Guinea, New Caledonia, and the main islands of Fiji—are remnants of the Gondwana landmass; they are large, mountainous, and geologically complex. Other islands in the region are volcanic in origin and form part of the Ring of Fire (see Figure 1.26). Many in this latter group are situated in boundary zones where tectonic plates are either colliding or pulling apart. For example, the Mariana Islands east of the Philippines are volcanoes that were formed when the Pacific Plate plunged beneath the Philippine Plate. The two islands of New Zealand were created when the eastern edge of the Indian-Australian Plate was thrust upward by its convergence with the Pacific Plate.

hot spots individual sites of upwelling material (magma) that originate deep in Earth’s mantle and surface in a tall plume; hot spots tend to remain fixed relative to migrating tectonic plates

atoll a low-lying island or chain of islets, formed of coral reefs that have built up on the circular or oval rims of a submerged volcano

Climate

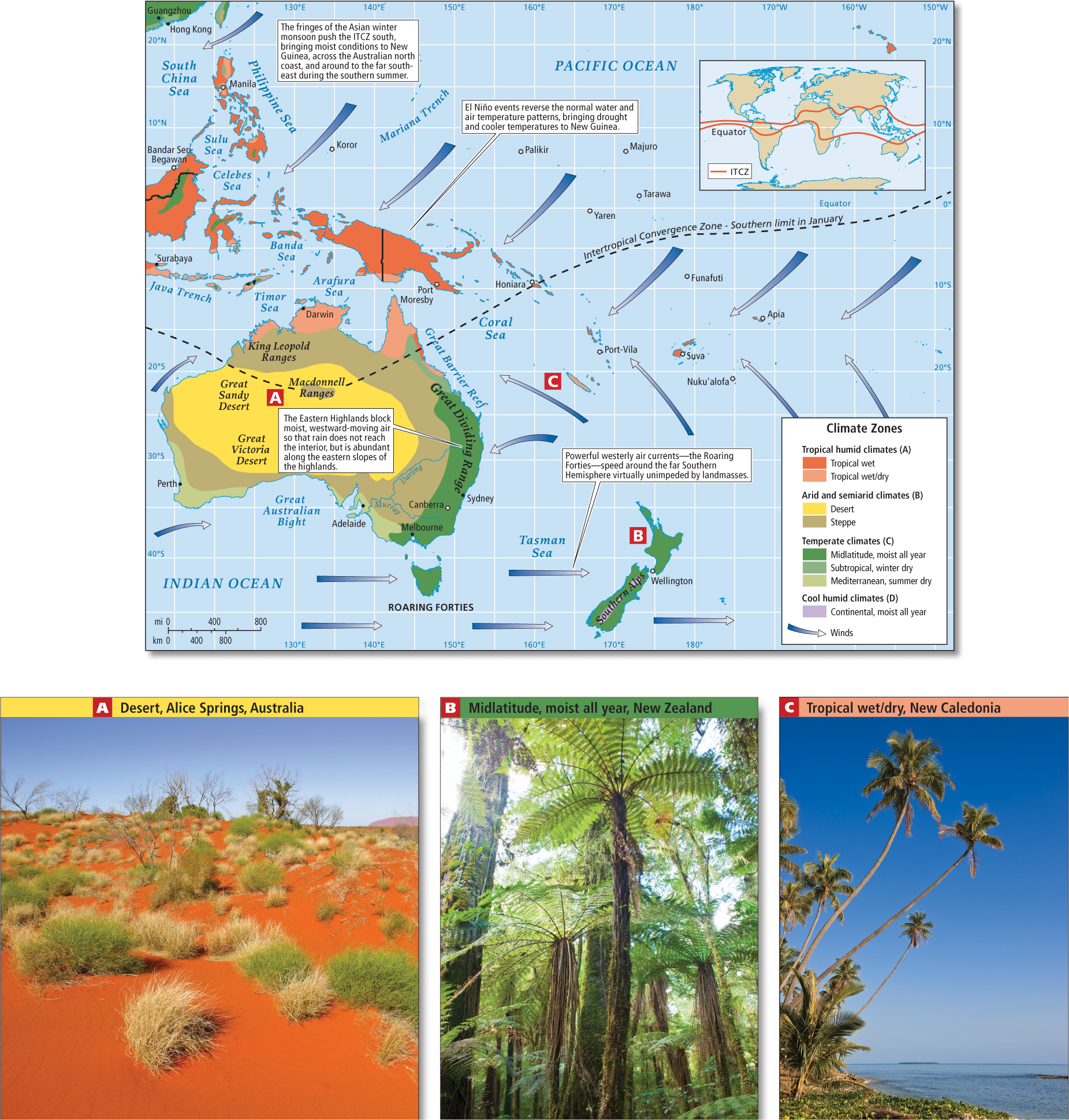

Although the Pacific Ocean stretches nearly from pole to pole, most of the land of Oceania is situated within the tropical and subtropical latitudes of that ocean. The tepid water temperatures of the central Pacific bring mild climates year-round to nearly all the inhabited parts of the region (Figure 11.5). Seasonal variations in temperature are greatest in the southernmost reaches of Australia and New Zealand.

Moisture and Rainfall

Maori Polynesian people indigenous to New Zealand

Roaring Forties powerful air and ocean currents at about 40° S latitude that speed around the far Southern Hemisphere virtually unimpeded by landmasses

By contrast, two-thirds of Australia is overwhelmingly dry (see Figure 11.5A). The dominant winds affecting Australia are the north and south easterlies (blowing east to west) that converge east of the continent. The Great Dividing Range blocks the movement of moist, westward-moving air so that rain does not reach the interior (an orographic pattern; see Figure 1.28). As a result, a large portion of Australia receives less than 20 inches (50 centimeters) of rain per year, and humans have found rather limited uses for this interior territory. But the eastern (windward) slopes of the highlands receive more abundant moisture. This relatively moist eastern rim of Australia was favored as a habitat by both the indigenous people and the Europeans who displaced them after 1800. During the southern summer, the fringes of the monsoon that passes over Southeast Asia and Eurasia bring moisture across Australia’s northern coast. There, annual rainfall varies from 20 to 80 inches (50 to 200 centimeters).

Overall, Australia is so arid that it has only one major river system, which is in the temperate southeast where most Australians live. There, the Darling and Murray rivers drain one-seventh of the continent, flowing west and south into the Indian Ocean near Adelaide. One measure of Australia’s overall dryness is that the entire average annual flow of the Murray-Darling river system is equal to just one day’s average flow of the Amazon in Brazil.

In the island Pacific, mountainous high islands also exhibit orographic rainfall patterns, with a wet windward side and a dry leeward side (see Figure 11.5C). Rainfall amounts on the low-lying islands vary considerably across the region. Some of the islands lie directly in the path of trade winds, which deliver between 60 and 120 inches of rain per year, on average. These islands support a remarkable variety of plants and animals. Other low-lying islands, particularly those on the equator, receive considerably less rainfall and are dominated by grasslands that support little animal life.

El Niño

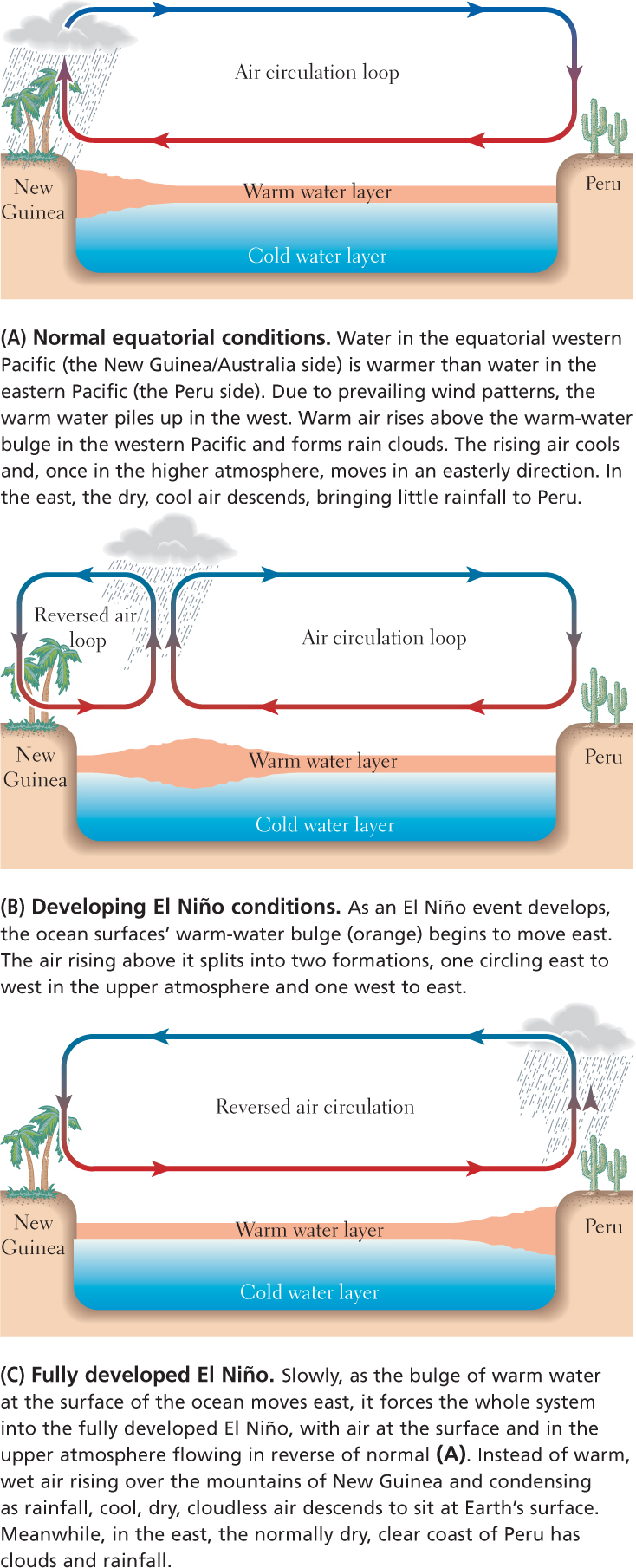

Recall from Chapter 3 the El Niño phenomenon, a pattern of shifts in the circulation of air and water in the Pacific that occurs irregularly every 2 to 7 years. Although these cyclical shifts, or oscillations, are not yet well understood, scientists have worked out a model of how the oscillations may occur (Figure 11.6).

The El Niño event of 1997–1998 illustrates the effects of this phenomenon. By December of 1997, the island of New Guinea (north of Australia; see the Figure 11.1 map) had received very little rainfall for almost a year. Crops failed, springs and streams dried up, and fires broke out in tinder-dry forests. The cloudless sky allowed heat to radiate up and away from elevations above 7200 feet (2200 meters), so temperatures at high elevations dipped below freezing at night for stretches of a week or more. Tropical plants died, and people unaccustomed to chilly weather sickened. Meanwhile, at the other end of the system, along the Pacific coasts of North, Central, and South America, the warmer-than-usual weather brought unusually strong storms, high ocean surges, and damaging wind and rainfall (see Figure 11.6C). In the 1980s, an opposite pattern, in which normal conditions become unusually strong, was identified and named La Niña. It is now understood that La Niña patterns can bring unusually severe precipitation events (including tornadoes and blizzards) to places from the Indian Ocean to North America. La Niña is thought to have played a role in the 2010–2011 major floods in Queensland, Australia, which were especially damaging because they followed an El Niño–connected lengthy drought.

Fauna and Flora

endemic belonging or restricted to a particular place

Animal and Plant Life in Australia

marsupials mammals that give birth to their young at a very immature stage and nurture them in a pouch equipped with nipples

monotremes egg-laying mammals, such as the duck-billed platypus and the spiny anteater

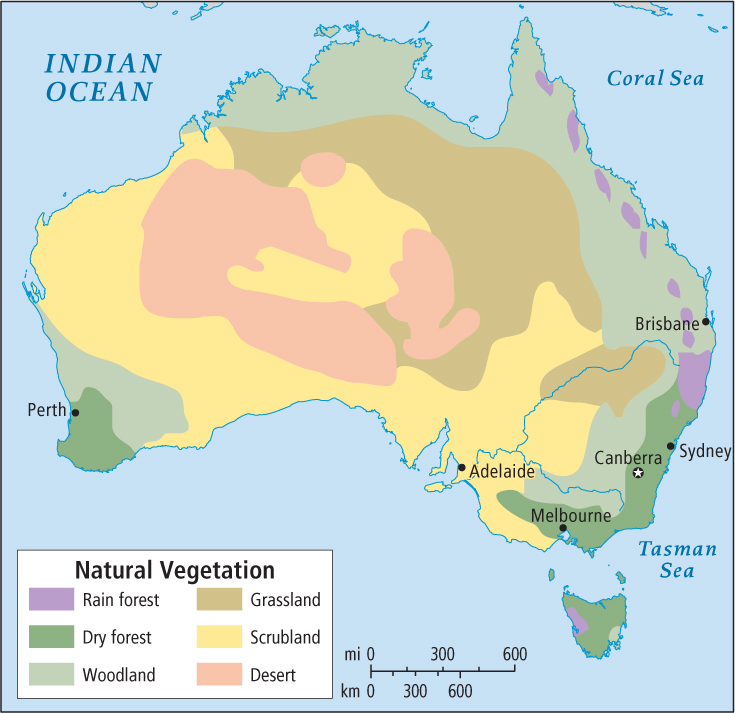

Most of Australia’s endemic plant species are adapted to dry conditions. Many of the plants have deep taproots to draw moisture from groundwater and small, hard, pale green or shiny leaves to reflect heat and to hold moisture. Much of the continent is grassland and scrubland with bits of open woodland; there are only a few true forests, found in pockets along the Eastern Highlands, the southwestern tip, and in Tasmania (Figure 11.7). Two plant genera account for nearly all the forest and woodland plants: Eucalyptus (450 species, often called gum trees) and Acacia (900 species, often called wattles).

Plant and Animal Life in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands

Naturalists and evolutionary biologists have long been interested in the species that inhabited the Pacific islands before humans arrived. Charles Darwin formulated many of his ideas about evolution after visiting the Galápagos Islands of the eastern Pacific (see Figure 3.1) and the islands of Oceania.

Islands gain plant and animal populations from the sea and air around them as organisms are carried from larger islands and continents by birds, storms, or ocean currents. Once these organisms “colonize” their new home, they may evolve over time into new species that are unique to one island. High, wet islands generally contain more varied species because their more complex environments provide niches for a wider range of wayfarers and thus more opportunities for evolutionary change.

Once they arrive, human inhabitants modify the flora and fauna of islands. In prehistoric times, Asian explorers in oceangoing canoes brought plants, such as bananas and breadfruit, and animals, such as pigs, chickens, and dogs, to Oceania. European settlers later brought grains, vegetables, fruits, invasive grasses, cattle, sheep, goats, rabbits, housecats, and rats. Today, human activities from tourism to military exercises to urbanization continue to change the flora and fauna of Oceania.  240. BREADFRUIT ADVOCATES SAY IT COULD SOLVE HUNGER IN TROPICAL REGIONS

240. BREADFRUIT ADVOCATES SAY IT COULD SOLVE HUNGER IN TROPICAL REGIONS

Generally, the diversity of land animals and plants is richest in the western Pacific, near the larger landmasses. It thins out to the east, where the islands are smaller and farther apart. The natural rain forest flora is rich and abundant on New Zealand, New Guinea, and the high islands of the Pacific. However, the natural fauna is much more limited on these islands. While New Guinea has fauna comparable to Australia, to which it was once connected via Sundaland (see Figure 10.5), New Zealand and the Pacific islands have no indigenous land mammals, almost no indigenous reptiles, and only a few indigenous species of frogs. New Zealand and the islands were never connected to Australia and New Guinea by a land bridge that land animals could cross. Two indigenous birds in New Zealand, the kiwi and the huge moa (a bird that grew up to 12 feet [3.7 meters] tall), were a major source of food for the Maori people. The moa was hunted to extinction before Europeans arrived. Today, New Zealand may well be the country with the most introduced species of mammals, fish, and fowl, nearly all brought in by European settlers.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

This largest region of the world is primarily water and has a very small population of just 38.7 million.

This largest region of the world is primarily water and has a very small population of just 38.7 million. The largest land area in Oceania is the continent of Australia.

The largest land area in Oceania is the continent of Australia. The thousands of islands of the Pacific were created either as a result of plate tectonics or volcanic activity.

The thousands of islands of the Pacific were created either as a result of plate tectonics or volcanic activity. The climate of most of the region is warm and humid nearly all the time.

The climate of most of the region is warm and humid nearly all the time. The fauna and flora of the region are unique in many distinctive ways that have informed our knowledge about evolution. Many species, such as marsupials and monotremes, are endemic to the region.

The fauna and flora of the region are unique in many distinctive ways that have informed our knowledge about evolution. Many species, such as marsupials and monotremes, are endemic to the region.