Environmental Issues

Geographic Insight 1

Climate Change and Water: Oceania’s sea level and freshwater resources are being impacted by climate change.

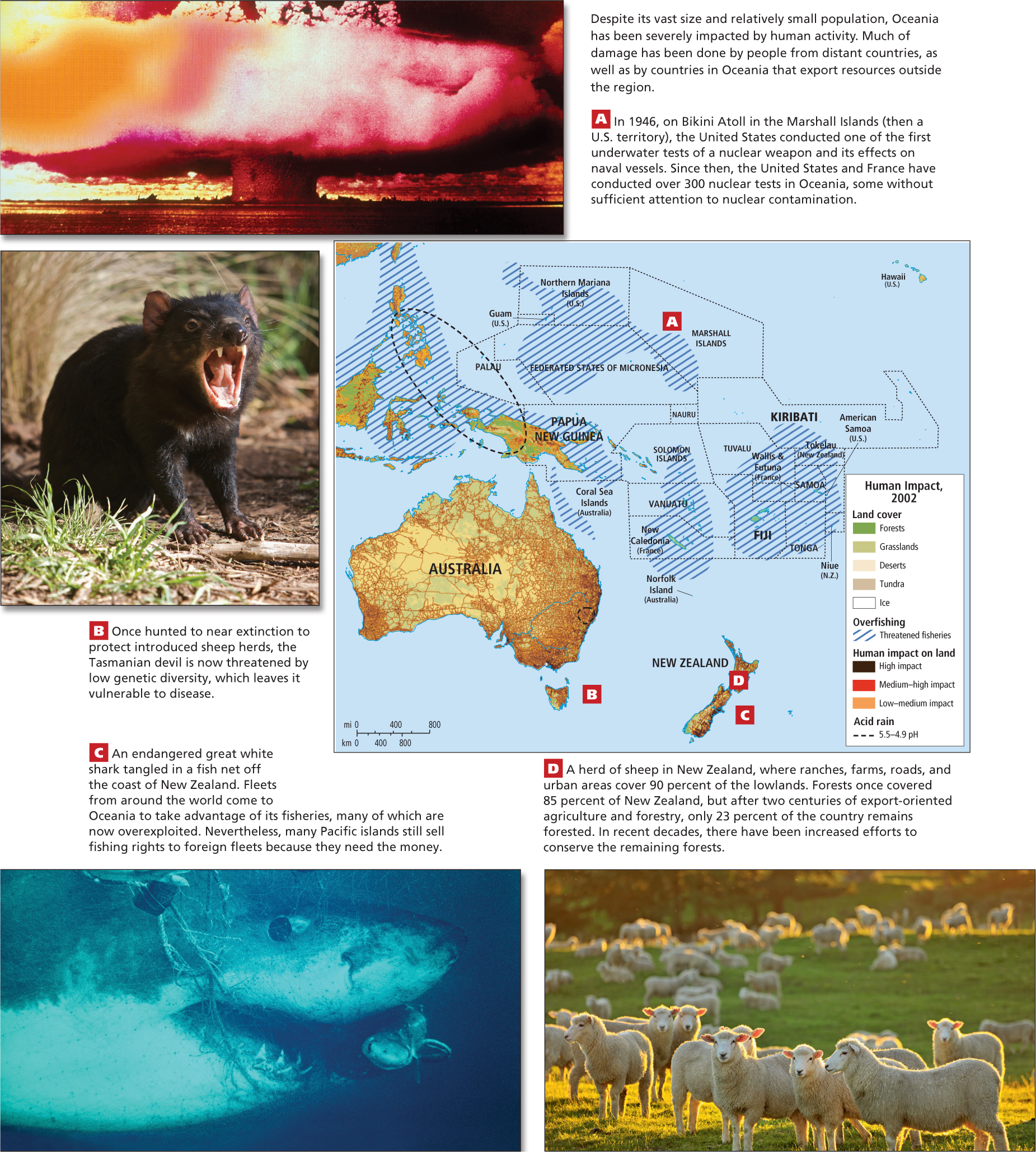

Oceania faces a host of environmental problems. Despite the region’s relatively small population, however, public awareness of environmental issues is keen. Global climate change, primarily warming, has brought a broad array of threats to the region’s ecology, as has the human introduction of many nonnative species. The expansion of herding, agriculture, fishing fleets, and the human population itself has also impacted much of the region (Figure 11.8).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about human impacts on the biosphere in Oceania, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Which nations have conducted the most nuclear tests in Oceania?

Which nations have conducted the most nuclear tests in Oceania?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why were plants and animals brought to Oceania from Europe?

Why were plants and animals brought to Oceania from Europe?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why might islands in Oceania be in a quandary over the activities of foreign fishing fleets?

Why might islands in Oceania be in a quandary over the activities of foreign fishing fleets?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What is the chief reason today for deforestation in New Zealand?

What is the chief reason today for deforestation in New Zealand?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

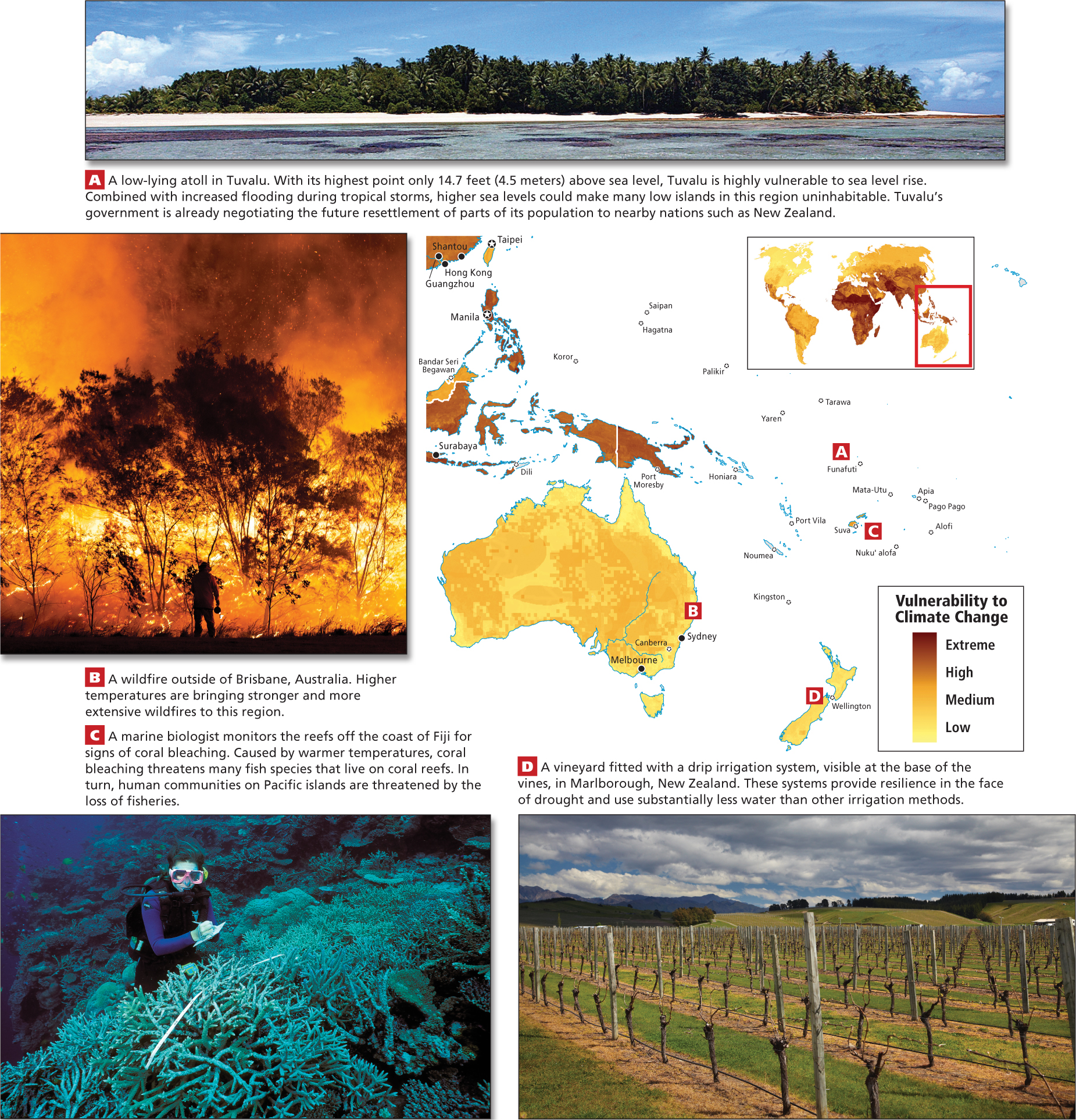

Global Climate Change

Oceania, with the exception of Australia, is a minor contributor of greenhouse gases. Australia has some of the world’s highest greenhouse gas emissions on a per capita basis (see Figure 1.23). As in the United States, Australia’s emissions result from the use of automobile-based transportation systems to connect a widely dispersed network of cities and towns. Also, as in the United States, heavy dependence on coal for electricity generation leads to high emissions. However, because Australia has a relatively small population (22.7 million people in 2010), it accounts for only slightly more than 1 percent of global emissions. Paradoxically, despite the negligible contributions of greenhouse gases made by the islands of the Pacific, they, as well as Australia, are highly vulnerable to the effects of global climate change (Figure 11.9).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the vulnerability to climate change in Oceania, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

If sea levels rise the 4 inches (10 centimeters) per decade as predicted by the International Panel on Climate Change, how many years will it be before the lowest-lying Pacific atolls, such as Tuvalu, disappear under water?

If sea levels rise the 4 inches (10 centimeters) per decade as predicted by the International Panel on Climate Change, how many years will it be before the lowest-lying Pacific atolls, such as Tuvalu, disappear under water?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What actions could humans take to increase the resilience of coral reefs to climate change?

What actions could humans take to increase the resilience of coral reefs to climate change?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why would irrigation be needed in New Zealand, which has a wet climate?

Why would irrigation be needed in New Zealand, which has a wet climate?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Sea Level Rise

Global warming may raise sea levels by melting glaciers and polar ice caps. Obviously, this issue is of great concern to residents of islands that already barely rise above the waves (see Figure 11.9A). If sea levels rise 4 inches (10 centimeters) per decade, as predicted by the International Panel on Climate Change, many of the lowest-lying Pacific atolls, such as Tuvalu, will disappear under water within 50 years. Other islands, some with already very crowded coastal zones, will see these zones shrink and become more vulnerable to storm surges and cyclones.

Other Water-Related Vulnerabilities

Much of Oceania is particularly vulnerable to the droughts and floods that could result from global climate change. Parts of Australia and some low, dry Pacific islands are already undergoing prolonged droughts and freshwater shortages that are requiring changes in daily life and livelihoods. The fear is that the severe droughts are not the usual periodic dry spells but may represent permanent alterations in rainfall patterns that could also worsen wildfires. Such fires emerged as a major issue in Australia in February 2009, when 173 people died in a rural firestorm near Melbourne (see Figure 11.9B).

As freshwater becomes scarcer across the region, virtual water (see Chapter 1) becomes an issue. All export-related activities that permanently consume or degrade freshwater in their extraction or production processes (such as mineral mining; oil and gas extraction; meat, wool, and wheat production; and tourism-related construction and maintenance) are essentially extracting virtual water from places that are already under water stress. If the true costs of this freshwater depletion were counted and added to the price of the products, these exports might no longer be competitive on the world market—at least not until all global producers saw virtual water accountability to be in their best interests and raised their prices accordingly.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Water Conservation

Oceania is a world leader in implementing alternative water technologies. Some are simple but effective age-old methods, such as harvesting rainwater from roofs and the ground for household use. Most buildings in rural Australia, New Zealand, and many Pacific islands get at least part of their water this way, relieving surface and groundwater resources. Australia and New Zealand are now stretching water resources further with extensive use of highly efficient drip irrigation technologies in agriculture (see Figure 11.9D) and new low-cost water-filtration techniques.

Another concern is the warming of the oceans, which can result in stronger tropical storms. Warmer ocean temperatures threaten coral reefs and the fisheries that depend on them by causing coral bleaching (see Figure 11.9C), a phenomenon affecting all reefs in this region in recent years, but especially the Great Barrier Reef. Because so many fish depend on reefs, coral bleaching also threatens many fishing communities. This is especially true on some of the Pacific islands that have few other local food resources.

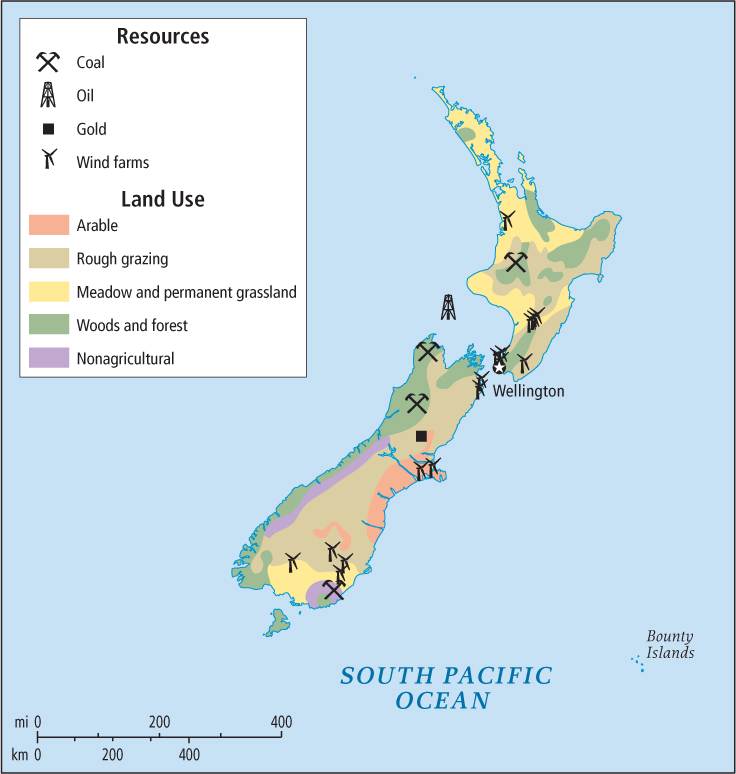

Responses to Potential Climate Change Crises

Oceania is pursuing a number of alternative energy strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Australia remains dependent on fossil fuel sales (primarily coal, but also crude oil and natural gas) to Asia, but it is pursuing renewable energy strategies for use at home. These include not only increasing power production from geothermal, solar, and biomass sources, but also, because of water shortages, decreasing the emphasis on hydropower. New Zealand has set a goal of obtaining 95 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2025. Much of this energy will come from wind power, which has excellent potential in this region, especially in areas near the Roaring Forties (see Figure 11.11). On low Pacific islands, solar energy is now the most widely used alternative to costly and polluting imported fuel.

Invasive Species and Food Production

Geographic Insight 2

Food and Development: European systems for producing food and fiber introduced into Oceania have greatly changed environments.

invasive species organisms that spread into regions outside of their native range, adversely affecting economies or environments

Australia

When Europeans first settled the continent, they brought many new animals and plants with them, sometimes intentionally, sometimes unintentionally. European rabbits are among the most destructive of the introduced species. Early British settlers who enjoyed eating rabbits brought them to Australia. Many were released for hunting, but with no natural predators, the rabbits multiplied quickly, consuming so much of the native vegetation that many indigenous animal species starved. Moreover, rabbits became a major source of agricultural crop loss and reduced the capacity of many grasslands to support herds of introduced sheep and cattle. Attempts to control the rabbit population by introducing European foxes and cats backfired as these animals became major invasive species themselves (Figure 11.10C). Foxes and cats have driven several native Australian predator species to extinction without having much effect on the rabbit population. Intentionally introduced diseases have proven more effective at controlling the rabbit population, though rabbits have repeatedly developed resistance to them.

Herding has also had a huge impact on Australian ecosystems. Because the climate is arid and soils in many areas are relatively infertile, the dominant land use in Australia is the grazing of introduced domesticated animals—primarily sheep, but also cattle. More than 15 percent of the land has been given over to grazing, and Australia leads the world in exports of sheep and cattle products.

Dingoes, the indigenous wild dogs of Australia (see Figure 11.10B), prey on the introduced sheep and young cattle. To separate the wild dogs from the herds, the Dingo Fence—the world’s longest fence—was built, extending 3488 miles (5614 kilometers). The fence is unfortunately a major ecological barrier to other wild species. Meanwhile, kangaroos (the natural prey of dingoes) have learned to live on the sheep side of the fence, where their population has boomed beyond sustainable levels.

New Zealand

New Zealand’s environment has been transformed by introduced species and food production systems even more extensively than Australia’s environment. No humans lived in New Zealand until about 700 years ago, when the Polynesian Maori people settled there. When they arrived, dense midlatitude rain forest covered 85 percent of the land. The Maori were cultivators who brought in yams and taro as well as other nonnative plants, rats, and birds. By the time of European contact (1642), forest clearing and overhunting by the Maori had already degraded many environments and driven several bird species to extinction.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Environmental Awareness in new Zealand

New Zealand is a global environmental leader. It formed the world’s first environmentally focused national political party in 1973 and spearheaded the world’s first “nuclear-free” zone in 1984. New Zealand’s government promotes a “clean and green” image internationally, but most New Zealanders acknowledge the severity of existing environmental problems, as well as the need for further action.

European settlement in New Zealand dramatically intensified environmental degradation associated with food production and invasive species. Attempts to re-create European farming and herding systems in New Zealand resulted in environments that today are actually hostile to many native species, a growing number of which are becoming extinct. Only 23 percent of the country remains forested, with ranches, farms, roads, and urban areas claiming more than 90 percent of the lowland area (Figure 11.11).

Most of the cleared land is used for export-oriented farming and ranching. Grazing has become so widespread that in New Zealand today there are 15 times as many sheep as people, and 3 times as many cattle. Both of these activities have severely degraded environments. Soils exposed by the clearing of forests proved infertile, forcing farmers and ranchers to augment them with agricultural chemicals. The chemicals, along with feces from sheep and cattle, have severely polluted many waterways, causing the extinction of some aquatic species.

Pacific Islands

In the Pacific islands, many unique species of plants and animals have been driven to extinction as islands were deforested and mined or converted to commercial agriculture. This was the case in Hawaii, which is home to more threatened or endangered species than any other U.S. state, despite having less than 1 percent of the U.S. landmass. There, extensive conversion of tropical forests to land used for the export crops of sugar cane and pineapples caused the extinction of numerous plant, bird, and land species.  239. HAWAII CONSIDERED AMERICA’S ENDANGERED SPECIES CAPITAL

239. HAWAII CONSIDERED AMERICA’S ENDANGERED SPECIES CAPITAL

Globalization and the Environment in the Pacific Islands

As the Pacific islands have become more connected to the global economy over the years, flows of resources and pollutants have increased dramatically. Mining, nuclear pollution, and tourism are all examples of how globalization has transformed environments in the Pacific islands.

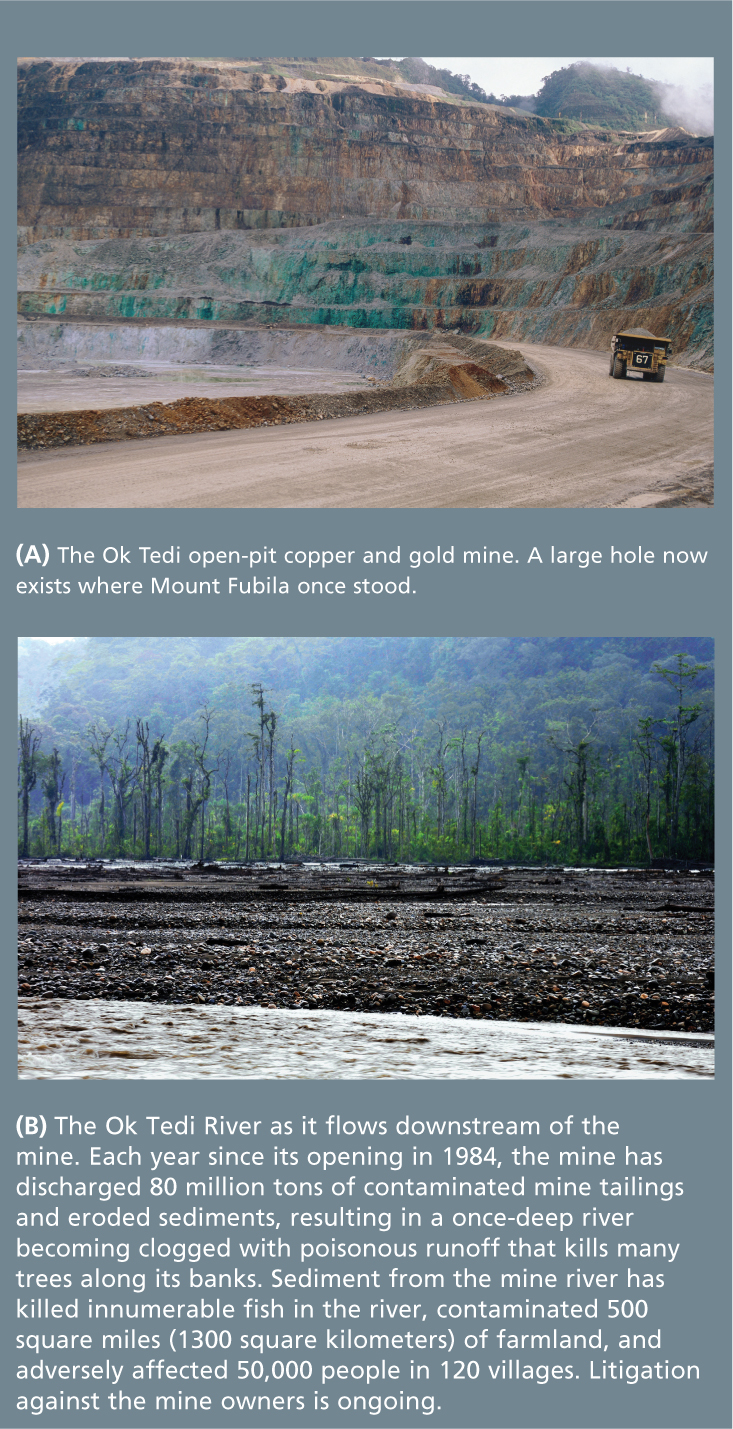

Mining in Papua New Guinea and Nauru

Foreign-owned mining companies that took advantage of poorly enforced or nonexistent environmental laws are responsible for major environmental damage in Oceania. In the Ok Tedi Mine on Papua New Guinea, huge amounts of mine waste devastated river systems (Figure 11.12). The environmental degradation forced tens of thousands of indigenous subsistence cultivators into new mining market towns, where their horticulture skills were of little use and where they needed cash to buy food and pay rent.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How many indigenous subsistence cultivators were forced off their land and into new mining market towns as a result of sediment and chemical pollution from the Ok Tedi Mine on Papua New Guinea?

How many indigenous subsistence cultivators were forced off their land and into new mining market towns as a result of sediment and chemical pollution from the Ok Tedi Mine on Papua New Guinea?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What evidence shows that this part of the polluted river flows through lowlands where flooding has taken place?

What evidence shows that this part of the polluted river flows through lowlands where flooding has taken place?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

In 2007, thirty thousand of these people sued the Australian parent mining company, which was then BHP Billiton, for U.S.$4 billion. Two villagers, Rex Dagi and Alex Maun, traveled to Europe and the United States to explain their cause and meet with international environmental groups. They and their supporters convinced U.S. and German partners in the Ok Tedi Mine to divest their shares.

The most extreme case of environmental disaster due to mining took place on the once densely forested Melanesian island of Nauru, one-third the size of Manhattan, located northeast of the Solomon Islands (see the Figure 11.1 map). Nauru’s wealth was based on proceeds from the strip-mining of high-grade phosphates derived from eons of bird droppings (guano) that are used to manufacture fertilizer. The mining companies were owned first by Germany, then by Japan, and finally by Australia, and for a time in the early 1970s Nauru had the highest per capita income in the world. Today, the phosphate reserves are depleted, the proceeds ill spent, and the environment destroyed. Junked mining equipment sits on miles of bleached white sand where forest once stood.

Nuclear Pollution

The geopolitical aspects of globalization have hit Oceania especially hard. Nuclear weapons testing by France and the United States from the 1940s to the 1960s (during the Cold War), as well as the acceptance of nuclear waste from various nuclear powers, have become major environmental issues for the Pacific islands (see Figure 11.8A). In New Zealand in July 1985, the French secret service blew up the ship Rainbow Warrior, owned by the antinuclear environmental group Greenpeace. In response, the 1986 Treaty of Rarotonga established the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone. Most independent countries in Oceania signed this treaty, which bans nuclear weapons testing and nuclear waste dumping on their lands. Because of political pressure from France and the United States, however, French Polynesia and U.S. territories such as the Marshall Islands have not signed the treaty.

Tourism

Even tourism, which until recently was considered a “clean” industry, can create environmental problems. Foreign-owned tourism enterprises have often accelerated the loss of wetlands and worsened beach erosion by clearing coastal vegetation for hotel construction, golf courses, and waterfront-related entertainment.

Tourism has also strained island water resources because of showering, laundering, and other services that consume fresh water. Furthermore, inadequate methods of disposing of sewage and trash from resorts have polluted many once-pristine areas. Ecotourism (see Chapter 3), aimed at reducing these impacts, is now a common element of development throughout the Pacific, but environmental impacts from ecotourism are still generally high.

The Great Pacific Garbage Island

When oceanographer Charles Moore found himself surrounded by a massive floating island of plastic garbage in the north Pacific in 1997, he thought it was an anomaly. But his investigations revealed that the throwaway concept of modern living was responsible. The island included plastic beverage bottles and caps along with Lego blocks, trash bags, toothbrushes, footballs, and kayaks—indeed, virtually every consumer product made. By 2008, several such garbage masses were floating in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Because modern plastics do not degrade, millions of seabirds and sea mammals die each year after ingesting bits of this trash. Whatever goes into the ocean eventually ends up on someone’s dinner plate. The following video tells more of the story: http://youtu.be/M7K-nq0xkWY.

The UN Encourages Pacific Resource Protection

Implementing the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) involves acknowledging that the globalization of Pacific island economies has undermined the environment. Based on the idea that all the problems of the world’s oceans are interrelated and need to be addressed as a whole, UNCLOS established rules governing all uses of the world’s oceans and seas and has been ratified by 157 countries (although not the United States).

The treaty allows islands to claim rights to ocean resources 200 miles (320 kilometers) out from their shores. Island countries can now make money by licensing privately owned fleets from Japan, South Korea, Russia, the United States, and elsewhere to fish within these offshore limits. As of yet, there is no overarching enforcement agency, and protecting the fisheries from overfishing by these rich and powerful licensees has turned out to be an enforcement nightmare for tiny island governments with few resources. Similarly, it has proven difficult to monitor and control the exploitation of seafloor mineral deposits by foreign mining companies.

241. ENDANGERED HAWAIIAN MONK SEAL POPULATION CONTINUES TO DECLINE

241. ENDANGERED HAWAIIAN MONK SEAL POPULATION CONTINUES TO DECLINE

243. SCIENTISTS WARN OF DEPLETION OF OCEAN FISH IN 40 YEARS

243. SCIENTISTS WARN OF DEPLETION OF OCEAN FISH IN 40 YEARS

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 1Climate Change and Water Sea level rise threatens to submerge some Pacific islands, and water supplies throughout the region may be strained as rainfall patterns change. If sea levels rise the predicted 4 inches per decade, many of the lowest-lying atolls will disappear under water, leaving a multitude of refugees. Warming oceans threaten coral reefs that are important to fisheries and local livelihoods.

Geographic Insight 1Climate Change and Water Sea level rise threatens to submerge some Pacific islands, and water supplies throughout the region may be strained as rainfall patterns change. If sea levels rise the predicted 4 inches per decade, many of the lowest-lying atolls will disappear under water, leaving a multitude of refugees. Warming oceans threaten coral reefs that are important to fisheries and local livelihoods. In an effort to combat global warming, renewable energy alternatives to fossil fuels are being pursued across the region. New Zealand has set a goal of obtaining 95 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2025.

In an effort to combat global warming, renewable energy alternatives to fossil fuels are being pursued across the region. New Zealand has set a goal of obtaining 95 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2025. Geographic Insight 2Food and Development Throughout Oceania, the introduction of food production systems from elsewhere has resulted in the spread of ecologically and economically damaging invasive plant and animal species.

Geographic Insight 2Food and Development Throughout Oceania, the introduction of food production systems from elsewhere has resulted in the spread of ecologically and economically damaging invasive plant and animal species. Globalization and the patterns of consumption by people who live far from the Pacific are seriously affecting human and animal life in this region.

Globalization and the patterns of consumption by people who live far from the Pacific are seriously affecting human and animal life in this region.