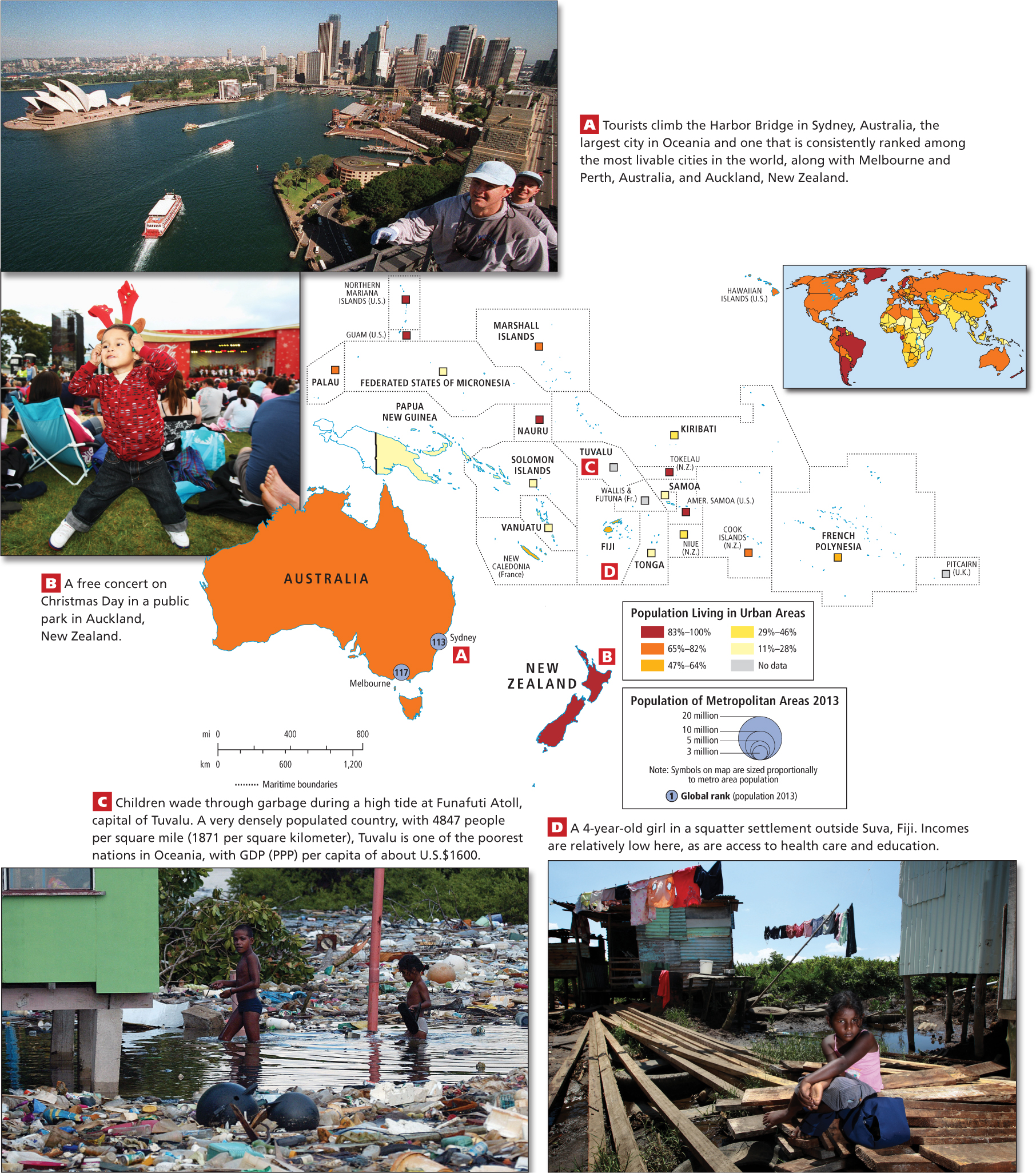

Population Patterns

Although Oceania occupies a huge portion of the planet, its total population is only 38.7 million people, close to that of the state of California (38 million) (Figure 11.17). The people of Oceania live on a total land area slightly larger than the contiguous United States but spread out in bits and pieces across an ocean larger than the Eurasian landmass. The Pacific islands, including Hawaii’s 1.74 million, have nearly 4.75 million people; Australia has 22.7 million; Papua New Guinea, 6.9 million; and New Zealand, 4.4 million.

Disparate Population Patterns in Oceania

Geographic Insight 4

Population and Urbanization: This largest region of the world is only lightly populated, but it is highly urbanized.

There are varying population patterns in Oceania. Like many wealthy countries, Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii have highly urbanized, relatively older, and more slowly growing populations, with life expectancies of close to 80 years. The Pacific islands and Papua New Guinea, like many developing countries, have much more rural, younger, and rapidly growing populations, with life expectancies in the 60s and low 70s. The overall trend throughout the region, however, is toward smaller families, aging populations, and urbanization.

Population densities remain low in Australia, at 7.8 people per square mile (3 per square kilometer) for the country as a whole and in Australia’s settled southeast about 50 per square mile (20 per square kilometer). New Zealand’s density is also low, at 41.4 per square mile (16 per square kilometer). In the Pacific islands, densities vary widely. Some are sparsely settled or uninhabited, while others—including some of the smallest, poorest, and lowest in elevation (and thus exposed to rising sea levels)—are extremely densely populated. For example, the Marshall Islands and Funafuti (Figure 11.18C), the capital of Tuvalu, have 772 and 4847 people, respectively, per square mile (298 and 1871, respectively, per square kilometer).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in Oceania, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

Approximately what percent of Australians live in cities?

Approximately what percent of Australians live in cities?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Notice the primary features of this photo. In what environmental zone is this settlement likely to be located?

Notice the primary features of this photo. In what environmental zone is this settlement likely to be located?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Given the contents of this photo, the caption, and what you have read about population trends, what would be your rationale for assuming that this girl likely is not the only child in her family?

Given the contents of this photo, the caption, and what you have read about population trends, what would be your rationale for assuming that this girl likely is not the only child in her family?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Urbanization in Oceania

The global trend of migration from the countryside to cities is highly visible in Oceania, where overall 66 percent of the population lives in urban areas, but in selected places (Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, Guam, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau) 80 to 100 percent of the population is urban (see Figure 11.18A). The shift from agricultural and resource-based economies toward service economies is a major driver of urbanization, especially in Australia, New Zealand, and some of the wealthier Pacific islands such as Hawaii and Guam. These trends are weakest in Papua New Guinea and many smaller Pacific islands (see Figure 11.18C, D). Nauru is a special case of extremely dense settlement and lack of balanced development.

Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand have among the highest percentages of city dwellers outside Europe. More than 82 percent of Australians live in a string of cities along the country’s relatively well-watered and fertile eastern and southeastern coasts. Similarly, 86 percent of New Zealanders live in urban areas. The vast majority of the people in these two countries live in modern comfort, work in a range of occupations typical of highly industrialized societies, and have access to tax-supported healthcare and leisure facilities (see Figure 11.18A). Vibrant, urban-based service economies employ about three-quarters of the population in both countries. Declining employment in mining and agriculture, where mechanization has dramatically reduced the number of workers needed, has also contributed to urbanization.

Pacific Islands

Throughout the Pacific, urban centers have transformed natural landscapes, and in some small countries, such as Guam, Palau, and the Marshall Islands, they have become the dominant landscape. Although cities are places of opportunity, they can also be sites of cultural change, conflict, and environmental hazards (see Figure 11.18C).

The great majority of Pacific island towns and all the capital cities are located in ecologically fragile coastal settings. Many of these waterfront towns were established during the colonial era as ports or docking facilities and were situated in places suitable for only limited numbers of people. Consequently, little land is available for development and access to housing is inadequate. Squatter settlements have been a visible feature of these urban areas for decades.

Multiculturalism has been enhanced by urbanization across the region. Many urban residents are letting go of the rural ways of their childhoods, as well as their ethnic identity and cultural commitments. Increasingly, people are marrying in town and across language divisions, having only one or two children, and creating new patterns of social alliances and networks. Along with the adoption of urban lifestyles, such cultural blending results in new social tensions, changing the very nature of social life in the island Pacific. Urban unemployment and unrest are on the rise, and low economic growth restricts the revenue available to governments to manage urban development.

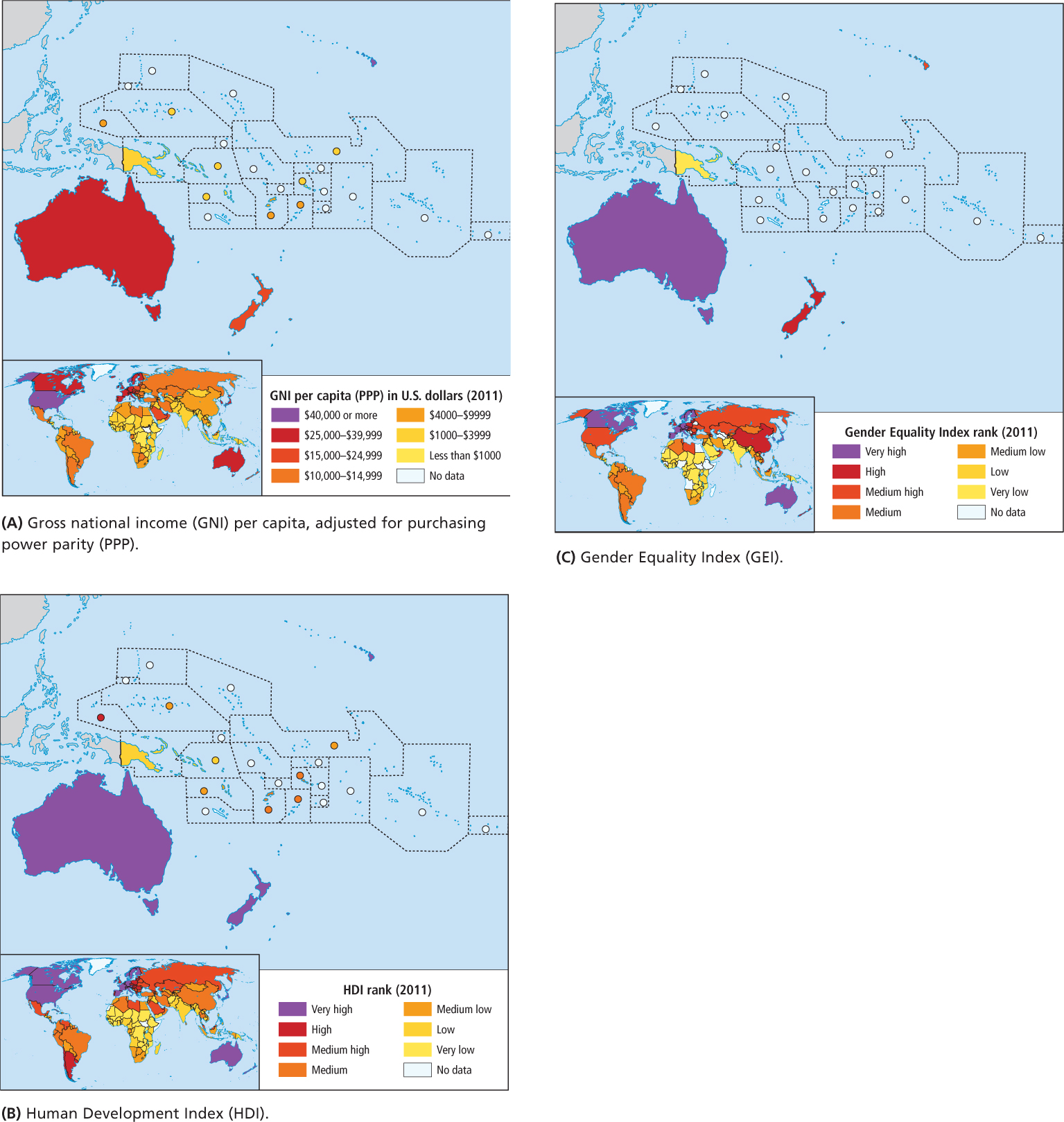

Human Well-Being in Oceania

Human well-being varies dramatically across this region as measured by the usual indicators used in this book—gross national income per capita (GNI per capita, adjusted for PPP), rank on the UN Human Development Index (HDI), and the Gender Equality Index (GEI). Over the last decade, Australia typically has ranked among the top 20 countries in GNI per capita PPP (in 2011, it ranked 18th). New Zealand has been among the top 25, but in 2011 it fell to 35th. Australia usually occupies one of the top 5 slots on the HDI (2nd in 2011). New Zealand usually falls at the lower end of highly developed countries on the HDI, but rose to 5th in 2011. Hawaii, part of the United States, typically has a GNI per capita PPP that is about $2000 higher than the average for the United States, and because it is a state with an unusually well-developed social welfare system, it would rank higher than the overall U.S. level of 4th on the HDI.

The maps of human well-being (Figure 11.19) illustrate these rankings. Figure 11.19A shows that, except for Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii, Oceania has low levels of GNI per capita. Figure 11.19B shows medium to low HDI rankings—again with the exceptions of Australia (2), New Zealand (5), and probably Hawaii. Although the Pacific islands have very low levels of income and well-being as measured in official statistics, it should be remembered that subsistence affluence (discussed) and strong communitarian values (see the discussion about the Pacific Way) can result in higher-than-expected actual well-being.

Figure 11.19C shows how well countries are ensuring gender equality (GEI) in three categories: reproductive health, political and education empowerment, and access to the labor market. With a high rank indicating that genders are tending toward equality, Australia (18) and New Zealand (32) had the best records in the region in 2011. Hawaii, however, ranked lower on this scale, closer to the level of the United States as a whole. All of the Pacific islands ranked lower yet, with the exceptions of Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. However, the apparently more equal pay for females and males in these two places should be assessed in light of the generally very low incomes on those islands. Overall across the region, few countries have reported sufficient statistics to determine the gap in pay between men and women.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 4Population and Urbanization Like many wealthy countries, Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii have highly urbanized, relatively older, and more slowly growing populations, with life expectancies of about 80 years. The Pacific islands and Papua New Guinea, like many developing countries, have populations that tend to be more rural, young, and rapidly growing, with life expectancies in the 60s and low 70s.

Geographic Insight 4Population and Urbanization Like many wealthy countries, Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii have highly urbanized, relatively older, and more slowly growing populations, with life expectancies of about 80 years. The Pacific islands and Papua New Guinea, like many developing countries, have populations that tend to be more rural, young, and rapidly growing, with life expectancies in the 60s and low 70s. Despite having overall very light population density, urbanization is the dominant settlement pattern in Oceania, associated with rapid and deep cultural change.

Despite having overall very light population density, urbanization is the dominant settlement pattern in Oceania, associated with rapid and deep cultural change. The great majority of Pacific island towns and all of the capital cities are located in ecologically fragile coastal settings.

The great majority of Pacific island towns and all of the capital cities are located in ecologically fragile coastal settings. Human well-being varies dramatically across the region, but subsistence affluence and communitarian values help alleviate some apparently poor circumstances.

Human well-being varies dramatically across the region, but subsistence affluence and communitarian values help alleviate some apparently poor circumstances.