Sociocultural Issues

The cultural sea change in Oceania away from Europe and toward Asia and the Pacific has been accompanied by new respect for indigenous peoples. In addition, a growing sense of common economic ground with Asia has heightened awareness of the attractions of Asian culture.

Ethnic Roots Reexamined

Until very recently, most people of European descent in Australia and New Zealand thought of themselves as Europeans in exile. Many considered their lives incomplete until they had made a pilgrimage to the British Isles or the European continent. In her book An Australian Girl in London (1902), Louise Mack wrote: “[We] Australians [are] packed away there at the other end of the world, shut off from all that is great in art and music, but born with a passionate craving to see, and hear and come close to these [European] great things and their home[land]s.”

These longings for Europe were accompanied by racist attitudes toward both indigenous peoples and Asians. Most histories of Australia written in the early twentieth century failed to even mention the Aborigines, and later writings described them as amoral. At midcentury there were numerous projects to take Aboriginal children from their parents and acculturate them to European ways in harsh boarding schools. From the 1920s to the 1960s, whites-only immigration policies barred Asians, Africans, and Pacific Islanders from migrating to Australia and discouraged them from entering New Zealand. As we have seen, trading patterns in that era further reinforced connections to Europe.

Weakening of the European Connection

When migration from the British Isles slowed after World War II, both Australia and New Zealand began to lure immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, many of whom had been displaced by the war. Hundreds of thousands came from Greece, Italy, and what was then Yugoslavia. The arrival of these non-English-speaking people began a shift toward a more multicultural society. The whites-only immigration policy was abandoned and people began to arrive from many places. There was an influx of Vietnamese refugees in the early 1970s, during the frantic exodus that followed the United States’ withdrawal from Vietnam. More recently, skilled workers from India and elsewhere in Asia have met the growing demand for information technology (IT) specialists throughout the service sector.

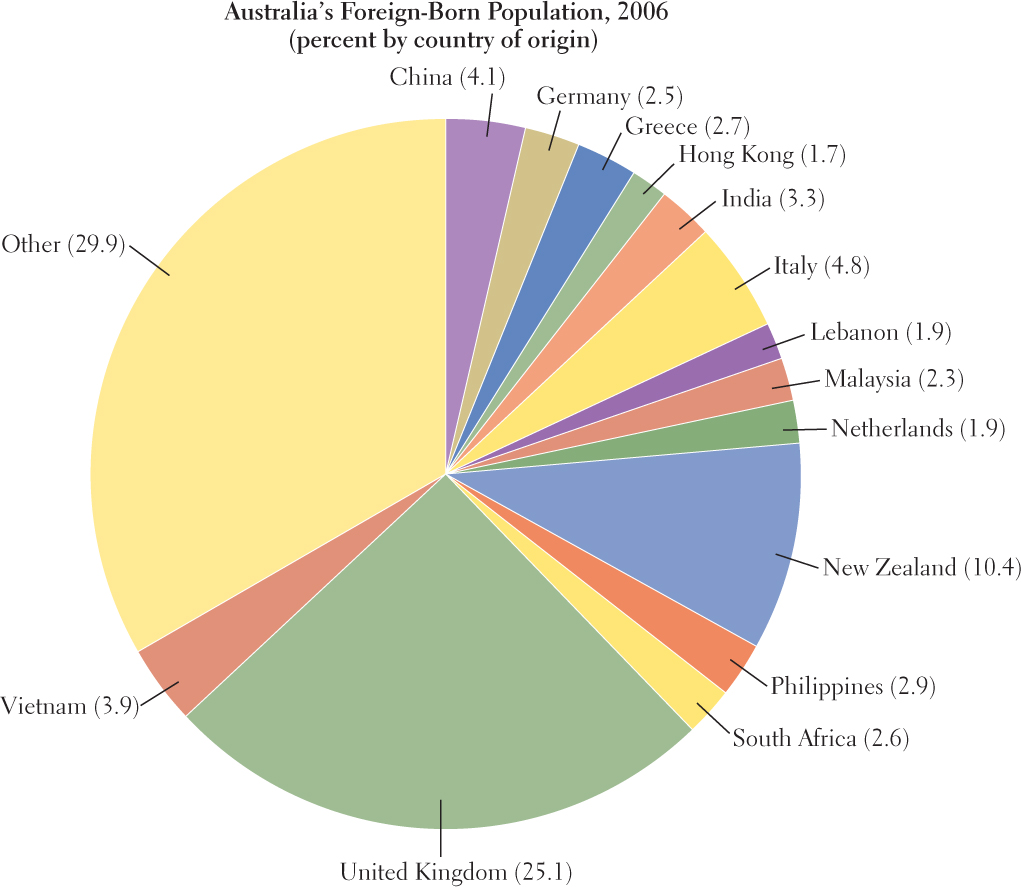

As of 2010, more than one-fourth of the Australian population was foreign born. The fastest-growing group was from India. Nonetheless, while new immigration policies are increasing the numbers of immigrants from China, Vietnam, and India, people of Asian birth or ancestry remain a minor percentage of the total population in both Australia and New Zealand. In 2006, the latest year for which complete statistics are available, of Australia’s foreign-born residents, 42 percent were from Europe; 15 percent were from Asia (Figure 11.20). New Zealand has similar proportions among its foreign-born residents, and most immigrants continue to come from Europe. Although (due to low birth rates and high immigration rates) Europeans are decreasing as a percentage of the population in both Australia and New Zealand, they will still constitute two-thirds or more of both countries’ populations by 2021 (see http://tinyurl.com/7ejcmp3).

The Social Repositioning of Indigenous Peoples in Australia and New Zealand

Perhaps the most interesting population change in Australia and New Zealand is one of identity. For the first time in 200 years, the number of people in both countries who claim indigenous origins is increasing. Between 1991 and 1996, the number of Australians claiming Aboriginal origins rose by 33 percent. By 2009, the Aboriginal population was estimated at 528,600. In New Zealand, the number claiming Maori background rose by 20 percent between 1991 and 2009 to 652,900.

These increases are due to changing identities, not to a population boom. More positive attitudes toward indigenous peoples have encouraged open acknowledgment of Aboriginal or Maori ancestry. Also, marriages between European and indigenous peoples are now more common. As a result, the number of people with a recognized mixed heritage is increasing.

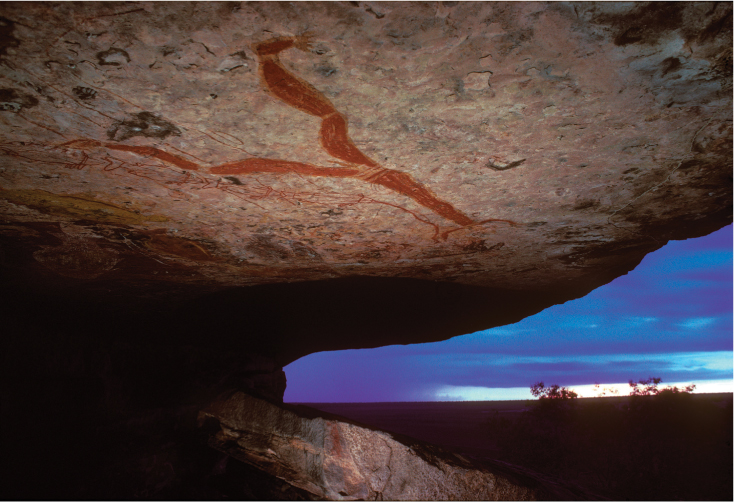

As society has acknowledged that discrimination has been the main reason for the low social standing and impoverished state of indigenous peoples, respect for Aboriginal and Maori culture has also increased. The Australian Aborigines base their way of life on the idea that the spiritual and physical worlds are intricately related (Figure 11.21). The dead are everywhere present in spirit, and they guide the living in how to relate to the physical environment. Much Aboriginal spirituality refers to the Dreamtime, the time of creation when the human spiritual connections to rocks, rivers, deserts, plants, and animals were made clear. However, very few Aboriginal people continue to practice their own cultural traditions or live close to ancient homelands. Instead, many live in impoverished urban conditions. In New Zealand, where the Maori constitute about 15 percent of the country’s population and Auckland now has the largest Polynesian population (including Native Maori) of any city in the world, there are now many efforts to bring Maori culture more into the mainstream of national life.

Aboriginal Land Claims

In 1988, during a bicentennial celebration of the founding of white Australia, a contingent of some 15,000 Aborigines protested that they had little reason to celebrate. During the same 200 years, they were assumed to have no prior claim to any land in Australia, had lost basic civil rights, and had effectively been erased from the Australian national consciousness. Into the 1960s, it was even illegal for Aborigines to drink alcohol.

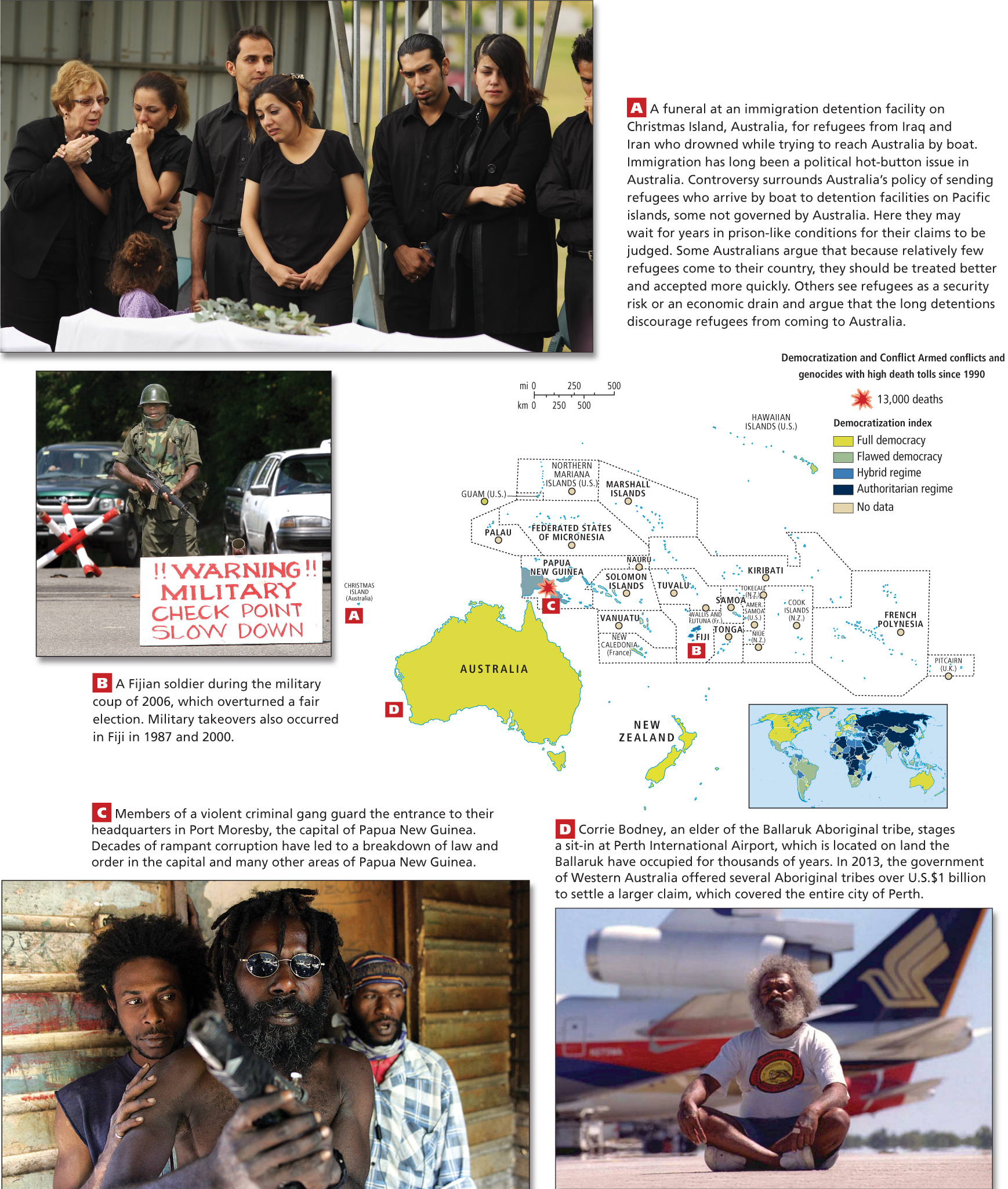

British documents indicate that during colonial settlement, all Australian lands were deemed to be available for British use. The Aborigines were thought to be too primitive to have concepts of land ownership because their nomadic cultures had “no fixed abodes, fields or flocks, nor any internal hierarchical differentiation.” The Australian High Court Mabo vs. Queensland decision, regarding native land rights, declared this position void in 1993. After that, Aboriginal groups began to win some land claims, mostly for land in the arid interior previously controlled by the Australian government. Figure 11.22 shows the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 2012, versions of which have stood on the grounds of Parliament in Canberra for more than 40 years. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy was instrumental in raising public awareness of injustices and remains a national symbol of Aboriginal civil rights. Court cases and other efforts to restore Aboriginal rights and lands continue (Figure 11.23D).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about power and politics in Oceania, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

When did Australia's whites-only immigration policy formally end?

When did Australia's whites-only immigration policy formally end?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

In Fiji, three coups d'état carried out by indigenous Fijians have removed legally elected governments headed by which group?

In Fiji, three coups d'état carried out by indigenous Fijians have removed legally elected governments headed by which group?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

How might corruption constrain political freedoms?

How might corruption constrain political freedoms?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Before 1993, why were Aborigines assumed to have no prior claim to land in Australia?

Before 1993, why were Aborigines assumed to have no prior claim to land in Australia?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Maori Land Claims

In New Zealand, relations between the majority European-derived population and the indigenous Maori have proceeded only somewhat more amicably than in Australia. In 1840, the Maori signed the Waitangi Treaty with the British, assuming they were granting only rights of land usage, not ownership (see Figure 11.24B). The Maori did not regard land as a tradable commodity, but rather as an asset of the people, used by families and larger kin groups to fulfill their needs. The geographer Eric Pawson writes: “To the Maori the land was sacred…[and] the features of land and water bodies were woven through with spiritual meaning and the Maori creation myth.” The British assumed that the treaty had given them exclusive rights to settle the land with British migrants and to extract wealth through farming, mining, and forestry.

By 1950, the Maori had lost all but 6.6 percent of their former lands to European settlers and the government. Maori numbers shrank from a probable 120,000 in the early 1800s to 42,000 in 1900, and the Maori came to occupy the lowest and most impoverished rung of New Zealand society. In the 1990s, however, the Maori began to reclaim their culture, and they established a tribunal that forcefully advances Maori interests and land claims through the courts. Since then, nearly half a million acres of land and several major fisheries have been transferred back to Maori control.

Nonetheless, the Maori still have notably higher unemployment, lower education levels, and poorer health than the New Zealand population as a whole.

Power and Politics: Different Political Cultures

Pacific Way the regional identity and way of handling conflicts based on notions of power and problem solving originating in the traditional culture of many Pacific Islanders

Democracy as it is practiced in Australia and New Zealand is a parliamentary system based on universal suffrage, debate, and majority rule. The Pacific Way is based on traditional notions of power and problem solving and refers to a way of settling issues based in the traditional culture of many Pacific Islanders. It favors consensus and mutual understanding over open confrontation, and respect for traditional leadership (especially the usually patriarchal leadership of families and villages) over free speech and other political freedoms. As such, the Pacific Way can embody very different definitions of human rights and corruption from parliamentary systems (see Figure 11.23B, C).

The Pacific Way as a political and cultural philosophy developed in Fiji around the time of its independence from the United Kingdom in 1970. It subsequently gained popularity in many Pacific islands, most of which gained independence in the 1970s and 1980s. The Pacific Way carries a flavor of resistance to Europeanization and has often been invoked to uphold the notion of a regional identity shared by Pacific islands that grows out of their unique history and social experience. It was particularly influential among educators given the task of writing new textbooks to replace those used by the former colonial masters. The new texts focused students’ attention away from Britain, France, or the United States and toward their own cultures. Appeals to the Pacific Way have also been used to uphold attempts by Pacific island governments to control their own economic development and solve their own political and social problems.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Value of the Pacific Way to Grassroots Sustainability

Regardless of its global political status, the Pacific Way is likely to endure, especially as a concept that upholds regional identity and traditional culture. Further, some organizations now use the Pacific Way as the basis of an integrated approach to economic development and environmental issues. For example, the South Pacific Regional Environmental Programme builds on traditional Pacific island economic activities—such as fishing and local traditions of environmental knowledge and awareness—to promote grassroots economic development and environmental sustainability.

In politics, the Pacific Way has occasionally been invoked as a philosophical basis for overriding democratic elections that challenge the traditional power of indigenous Pacific Islanders. In 1987, 2000, and 2006, indigenous Fijians used the Pacific Way to justify coups d’état against legally elected governments (see Figure 11.23B). All three of the overthrown governments were dominated by Indian Fijians, the descendants of people from India whom the British brought to Fiji more than a century ago to work on sugar plantations.

Fiji’s population is now about evenly divided between indigenous Fijians and Indian Fijians. Indigenous Fijians are generally less prosperous and tend to live in rural areas where community affairs are still governed by traditional chiefs. By contrast, Indian Fijians hold significant economic and political power, especially in the urban centers and in areas of tourism and sugar cultivation. In response to the coups, many Indian Fijians left the islands, resulting in a loss of badly needed skilled workers, which has slowed economic development.

Political responses around Oceania to the Fiji coups have been divided. Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (via APEC and the state government of Hawaii) have demanded that the election results stand and the Indian Fijians be returned to office. But much of Oceania has referenced the Pacific Way in arguments supporting the coup leaders. As in Fiji, those who govern many of the Pacific islands are leaders of indigenous descent who have not always had the strongest respect for political freedoms, especially when their hold on power is threatened (see Figure 11.23C).

On the global stage, Fiji has been suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations (a union of former British colonies) for subverting majority-rule democracy. As a result, it is ineligible for Commonwealth aid and is not allowed to participate in Commonwealth sports events. Because sports play a central role in Pacific identity (see “Sports as a Unifying Force” below), this latter sanction carries significant weight.

Forging Unity in Oceania

Although wide ocean spaces and the great diversity of languages in the region sometimes make communication difficult, travel, sports, and festivals (Figure 11.24) are three forces that help bring the people of Oceania closer together.

Languages in Oceania

The Pacific islands—most notably Melanesia—have a rich variety of languages. In some cases, the islands in a single chain have several different languages. A case in point is Vanuatu, a chain of 80 mostly high volcanic islands to the east of northern Australia. At least 108 languages are spoken by a population of just 180,000—an average of 1 language for every 1600 people.

pidgin a language used for trading; made up of words borrowed from the several languages of people involved in trading relationships

Interisland Travel

One way in which unity is manifested in Oceania is interisland travel. Today, people travel in small planes from the outlying islands to hubs such as Fiji, where jumbo jets can be boarded for Auckland, Melbourne, and Honolulu. Cook Islanders call these little planes “the canoes of the modern age,” and people travel for many reasons. Dancers from across the region attend the annual folk festival in Brisbane; businesspeople from Kiribati, Micronesia, can fly to Fiji to take a short course at the University of the South Pacific; a Cook Islands teacher can take graduate training in Hawaii; and sports fans can visit multiple locations over the course of a lifetime.

Sports as a Unifying Force

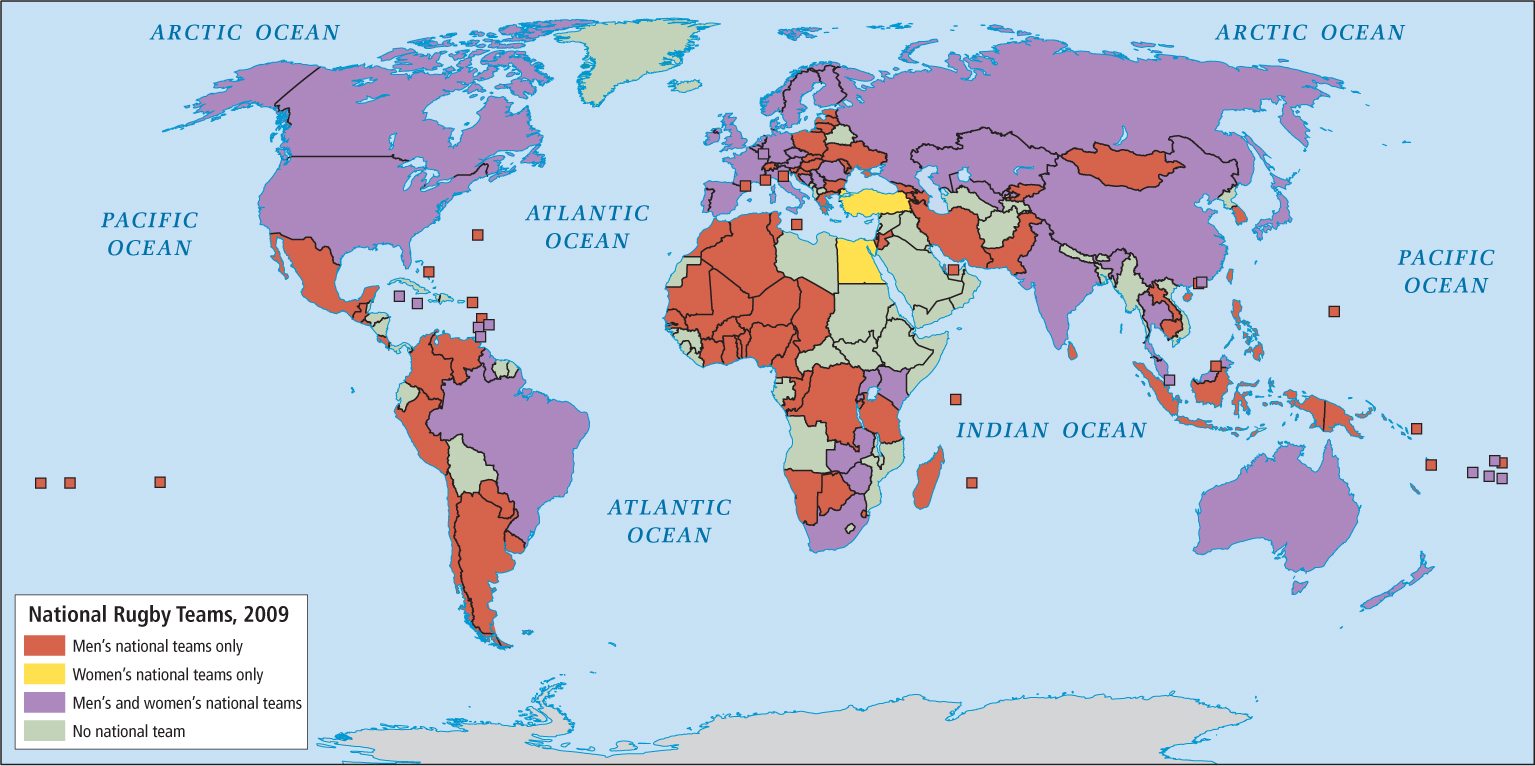

Sports and games are a major feature of daily life throughout Oceania. The region has shared sports traditions with, and borrowed them from, cultures around the world. Surfing evolved in Hawaii and, like outrigger sailing and canoeing, derives from ancient navigational customs that matched human wits against the power of the ocean. On hundreds of Pacific islands and in Australia and New Zealand, rugby, volleyball, soccer, and cricket are important community-building activities. Baseball is a favorite in the parts of Micronesia that were U.S. trust territories. Women compete in the popular sport of netball (similar to basketball but without a backboard).

Pan-Oceania sports competitions are the single most common and resilient link among the countries of the region. Attendance at regional sports events is so desirable that low-income islanders will hold yard sales and raffles to amass the cash necessary to make the trip. The centrality of such competitions in daily life encourages regional identity and provides opportunities for ordinary citizens to travel extensively around the region and to other parts of the world.

The haka (Figure 11.25) is an example of how, in the postcolonial modern era, indigenous culture in Oceania is being revived, celebrated, and appropriated in new places by those who wish to project a multicultural image. The haka is a highly emotional and physical dance traditionally performed by the Maori to motivate fellow warriors and intimidate opponents before entering battle. Dances like this have long been a part of many cultures in the islands of Oceania, but the haka has now become an integral part of rugby, the region’s most popular sport (Figure 11.26). Before almost every international match for the past century, the All Blacks (the New Zealand men’s rugby team) have performed the haka: chanting, screaming, jumping, stomping their feet, poking out their tongues, widening their eyes to show the whites, and beating their thighs, arms, and chests.

Outside of Oceania, those who perform the haka include the rugby teams at Jefferson High in Portland, Oregon, and Middlebury College in Vermont, and the football teams at Brigham Young University and the University of Hawaii. All of these teams have players who are of Polynesian heritage. Most practitioners speak of the haka as filling them with the necessary exuberance, aggression, and spirituality to play a vigorous and successful game. To see videos of a haka, go to http://www.YouTube.com and type in haka.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Oceania’s long-standing cultural and economic links to Europe are being challenged by reinvigorated native traditions and identities and by economic globalization, which is increasing the region’s links to Asia.

Oceania’s long-standing cultural and economic links to Europe are being challenged by reinvigorated native traditions and identities and by economic globalization, which is increasing the region’s links to Asia. The number of Asian immigrants into Australia and New Zealand has been increasing over the past two decades, while the number of Europeans has been declining. Asians, however, still comprise only a small minority of the populations of both Australia and New Zealand.

The number of Asian immigrants into Australia and New Zealand has been increasing over the past two decades, while the number of Europeans has been declining. Asians, however, still comprise only a small minority of the populations of both Australia and New Zealand. Governance in Oceania is for the most part based on democratic principles with regular elections; however; traditional power holders have staged coups that have negated or threatened political freedoms.

Governance in Oceania is for the most part based on democratic principles with regular elections; however; traditional power holders have staged coups that have negated or threatened political freedoms. Sports and festivals are unifying forces for the region, inspiring fundraisers that allow ordinary citizens to travel to games, thus reinforcing regional and ethnic identity.

Sports and festivals are unifying forces for the region, inspiring fundraisers that allow ordinary citizens to travel to games, thus reinforcing regional and ethnic identity.

Gender Roles in Oceania

Geographic Insight 5

Gender, Power, and Politics: Changes in political empowerment have taken different forms across Oceania, but there is a general trend toward a more active role for women.

Perceptions of Oceania are colored by many myths about how men and women are and should be. As always, the realities are more complex.

Gender Myths and Realities

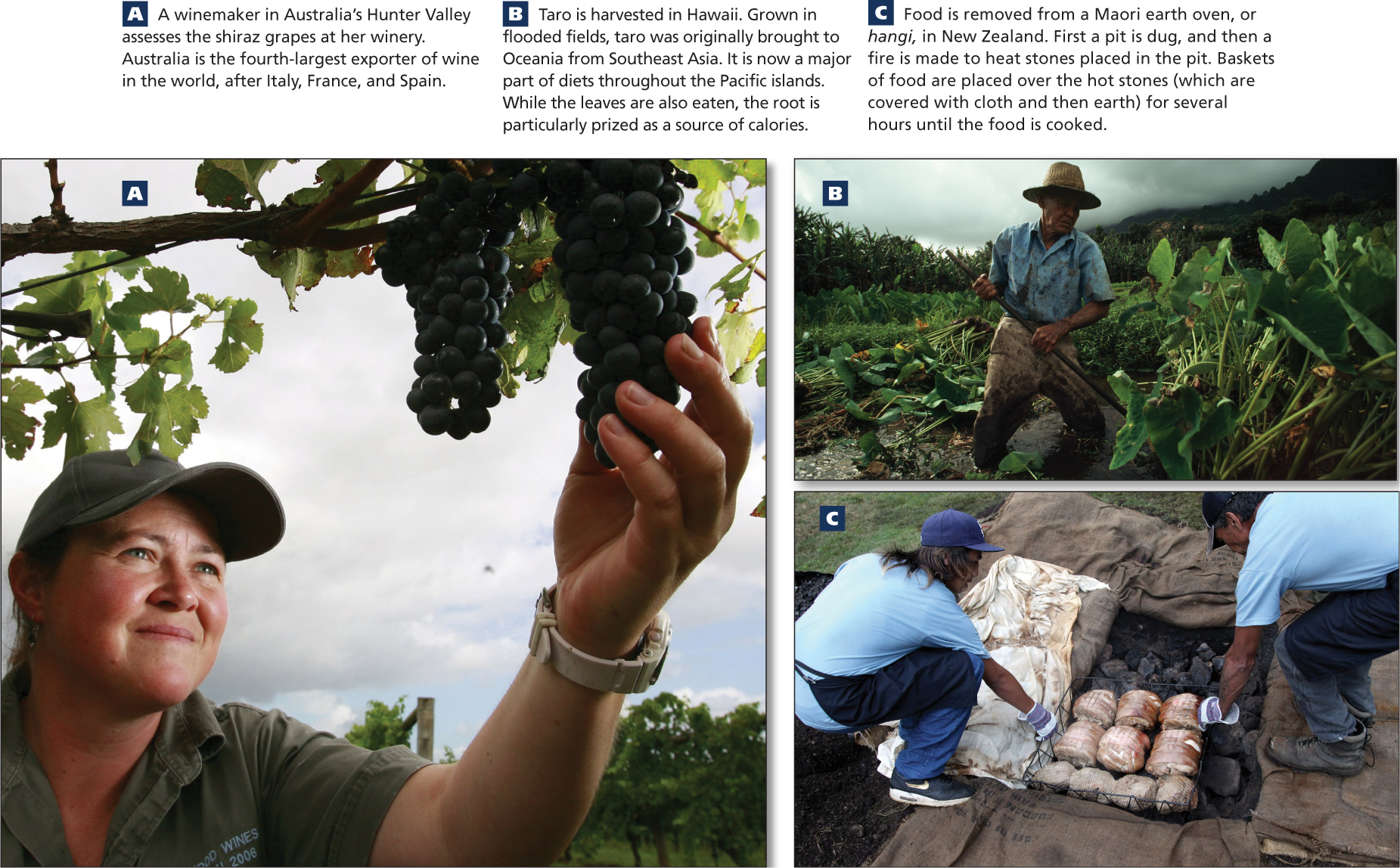

Because of Oceania’s cultural diversity, there are many different roles for men and women. In the Pacific islands, men traditionally were cultivators, deepwater fishers, and masters of seafaring. In Polynesia, men also were responsible for many aspects of food preparation, including cooking. In the modern world, men fill many positions, but idealized male images continue to be associated with vigorous activities.

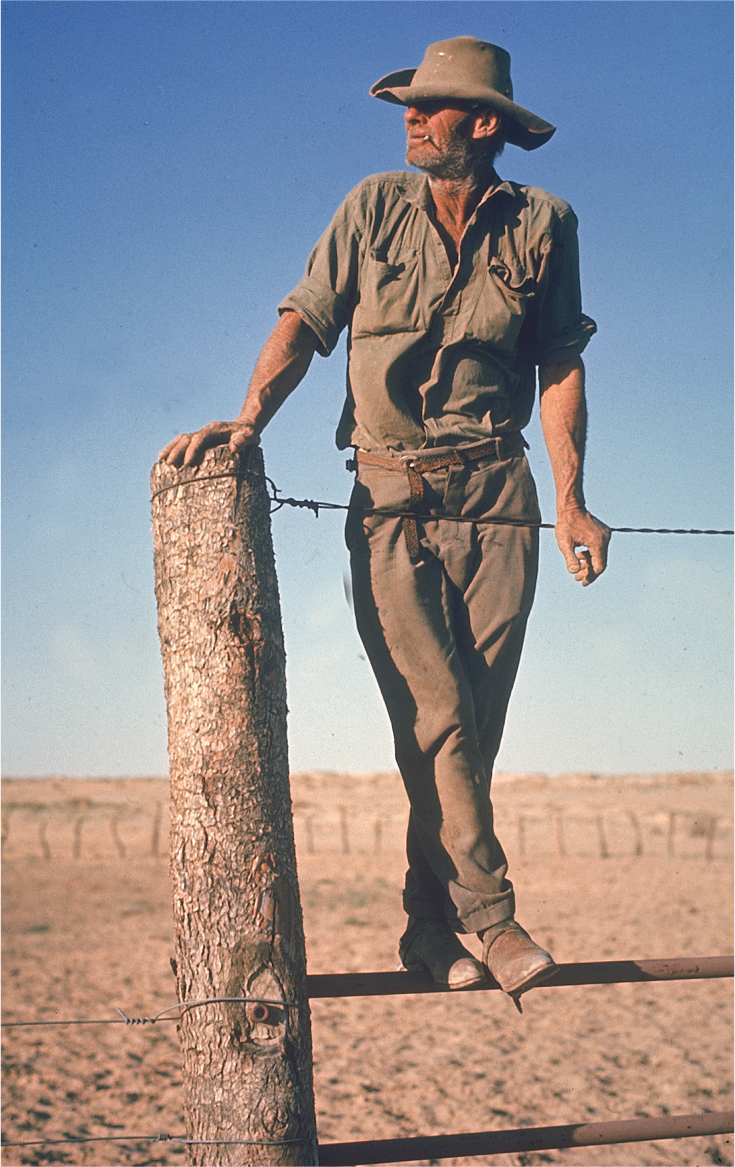

In Australia and New Zealand, the hypermasculine, white, working-class settler has long had prominence in the national mythologies. In New Zealand, he was a farmer and herdsman. In Australia, he was more often a many-skilled laborer—a stockman, sheep shearer, cane cutter, or digger (miner)—who possessed a laconic, laid-back sense of humor. Labeled a “swagman” for the pack he carried, he went from station (large farm) to station or mine to mine, working hard but sporadically, gambling and drinking, and then working again until he had enough money or experience to make it in the city (Figure 11.27). There, he often felt ill at ease and chafed to return to the wilds. Now immortalized in songs (“Waltzing Matilda,” for example), novels, and films, these men are portrayed as a rough and nomadic tribe whose social life is dominated by male camaraderie and frequent brawls. No small part of this characterization of males derived from the fact that many of Australia’s first immigrants were convicts.

Today, as part of larger efforts to recognize the diversity of Australian society, new ways of life for men are emerging and are breaking down the national image of the tough male loner. Nonetheless, the old model persists and remains prominent in the public images of Australian businessmen, politicians, and movie stars.

Perhaps the most enduring myth Europeans created regarding Oceania was their characterization of the women of the Pacific islands as gentle, simple, compliant love objects. (Tourist brochures still promote this notion.) There is ample evidence to suggest that Pacific Islanders did have more sexual partners in a lifetime than Europeans did. However, the reports of unrestrained sexuality related by European sailors were no doubt influenced by the exaggerated fantasies one might expect from all-male crews living at sea for months at a time. The notes of Captain James Cook are typical: “No women I ever met were less reserved. Indeed, it appeared to me, that they visited us with no other view, than to make a surrender of their persons.” Over the years, such notions about Pacific island women have been encouraged by the paintings and prints of Paul Gauguin (Figure 11.28), the writings of novelist Herman Melville (Typee), and the studies of anthropologist Margaret Mead (Coming of Age in Samoa), as well as by movies and musicals such as Mutiny on the Bounty and South Pacific.

In reality, women’s roles in the Pacific islands varied considerably from those in Europe, but not in the ways European explorers imagined. Women often exercised a good bit of power in family and clan, and their power increased with motherhood and advancing age. In Polynesia, a woman could achieve the rank of ruling chief in her own right, not just as the consort of a male chief. Women were primarily craftspeople, but they also contributed to subsistence by gathering fruits and nuts and by fishing. And in some places—Micronesia, for example—lineage was established through women, not men.

Gender, Democracy, and Economic Empowerment

Today there is a trend toward equality across gender lines throughout Oceania, but there is persistent inequality as well. A striking disparity is emerging between Australia and New Zealand (where women are gaining political and economic empowerment) and Papua New Guinea and the Pacific islands (where change is much slower).

In Australia and New Zealand, women’s access to jobs and policy-making positions in government has improved, particularly over the last few decades. New Zealand and the Australian province of South Australia were among the first places in the world to grant European women full voting rights (1893 and 1895, respectively). New Zealand has elected two female prime ministers, and in 2010 Australia elected a woman prime minister, Julia Gillard. Moreover, in both countries, according to the 2011 Inter-Parliamentary Union report on women in Lower Houses of Parliament, the proportion of females in national legislatures (32.2 percent in New Zealand, 24.7 percent in Australia) is well above the global average of 18 percent. In Papua New Guinea and the Pacific islands, women are generally far less empowered politically and economically. No woman has yet been elected to a top-level national office, and women are a tiny minority in national legislatures, if present at all.

In both Australia and New Zealand, young women are pursuing higher education and professional careers and postponing marriage and childbearing until their thirties. (This is also a trend in Hawaii, Guam, and the islands with French affiliation.) Nonetheless, both societies continue to reinforce the housewife role for women in a variety of ways. For example, the expectation is that women, not men, will interrupt their careers to stay home to care for young or elderly family members. Women in Australia receive, on average, only about 70 percent of the pay that men receive for equivalent work. This is, however, a smaller gender pay gap than in many other developed countries.

Throughout Papua New Guinea and the Pacific islands, gender roles and relationships vary greatly over the course of a lifetime. Because of the emphasis on community, male and female Pacific Islanders contribute to family assets through the formal and informal economies. Traditionally, men are the boat builders, navigators, fishers, and house builders. And they are the usual preparers of food, though women often supply some of the ingredients through their gathering and cultivating efforts (Figure 11.29). Most traders in marketplaces are women, and, aside from fish, the items they sell are also made and transported by women. Many young women today fulfill traditional roles as mates and mothers and practice a wide range of domestic crafts, such as weaving and basketry. In middle age, however, these same women may return to school and take up careers. With the aid of government scholarships, some Pacific Islander women pursue higher education or job training that takes them far from the villages where they raised their children. Thus the expectation that Aurora (in this chapter’s opening vignette) will study far from home and then support her peers and elders is in line with evolving gender roles in Pacific ways of life. Aurora can expect that with accumulating age and experience, she will be boosted into a position of considerable power in her community.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 5Gender, Power, and Politics Gender roles and relationships vary considerably in Oceania. In Australia and New Zealand, compared with elsewhere in the region, women generally are better off in terms of political power and pay equity with men.

Geographic Insight 5Gender, Power, and Politics Gender roles and relationships vary considerably in Oceania. In Australia and New Zealand, compared with elsewhere in the region, women generally are better off in terms of political power and pay equity with men. In some traditional societies, especially those on Pacific islands with more than basic education, women can inherit or personally accrue considerable power in their own communities over the course of a lifetime.

In some traditional societies, especially those on Pacific islands with more than basic education, women can inherit or personally accrue considerable power in their own communities over the course of a lifetime.