1.2 Population

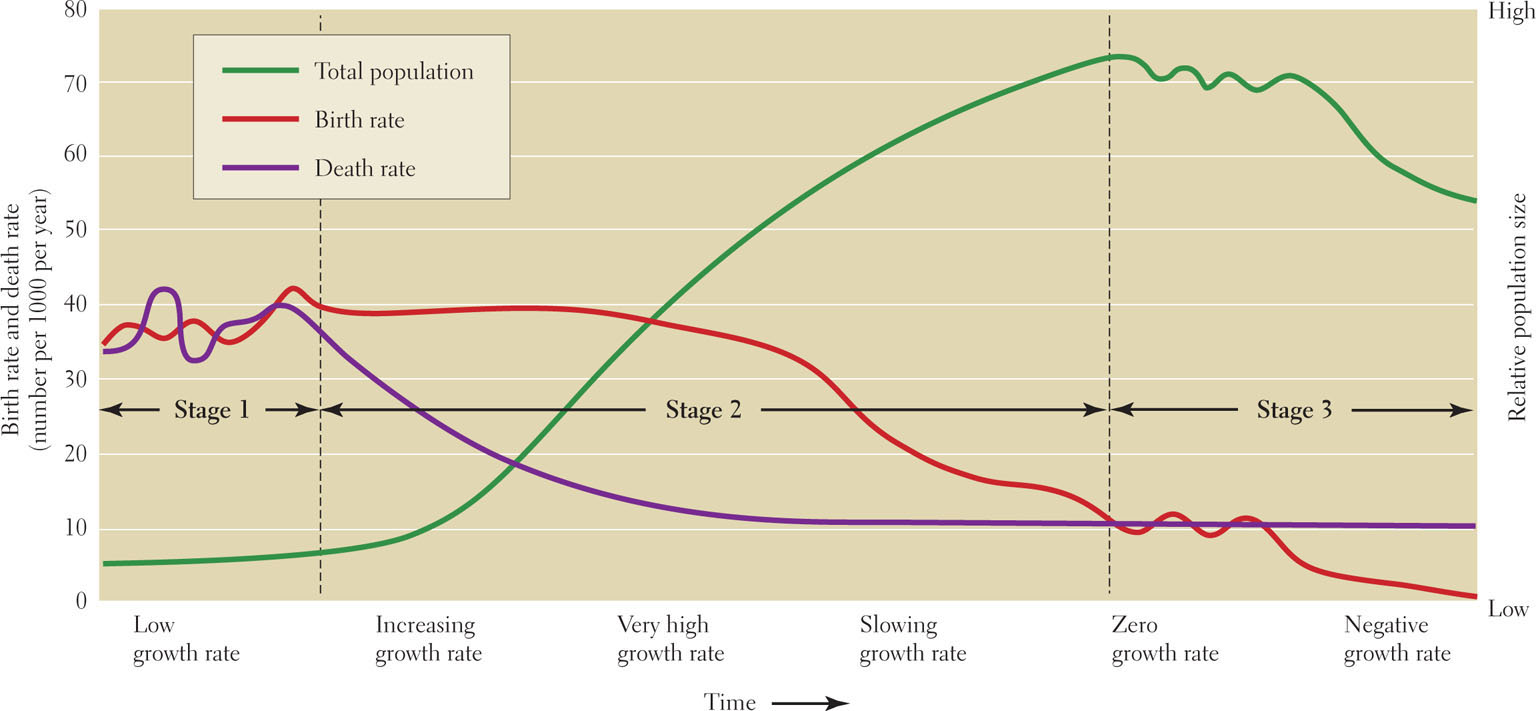

To study population is to study the growth and decline of numbers of people on Earth, their distribution across the Earth’s surface in terms of age and sex, as well as the reasons that prompt them to move. Over the last several hundred years, the global human population has boomed, but growth rates are now slowing in most societies and, in a few, have even begun to decline (a process that is also called negative growth). Much of this pattern has to do with changes in economic development and gender roles that have reduced incentives for large families.

Global Patterns of Population Growth

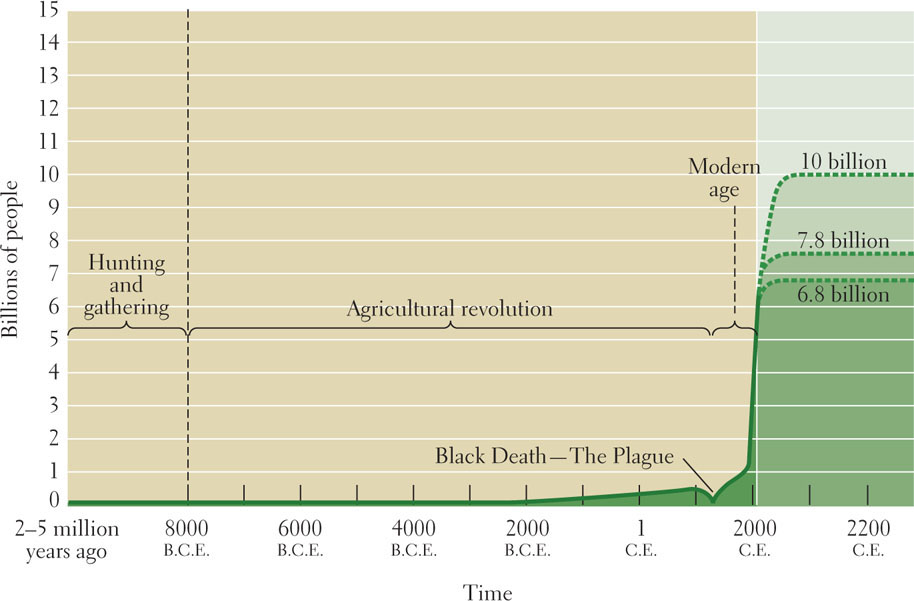

It took between 1 million and 2 million years (at least 40,000 generations) for humans to evolve and to reach a global population of 2 billion, which happened around 1945. Then, remarkably, in just 66 years—by October of 2011—the world’s population more than tripled to 7 billion (Figure 1.7). What happened to make the population grow so quickly in such a short time?

The explanation lies in changing relationships between humans and the environment. For most of human history, fluctuating food availability, natural hazards, and disease kept human death rates high, especially for infants. Out of many pregnancies, a couple might raise only one or two children. Also, pandemics, such as the Black Death in Europe and Asia in the 1300s, killed millions in a short time.

An astonishing upsurge in human population began about 1500, at a time when the technological, industrial, and scientific revolutions were beginning in some parts of the world. Human life expectancy increased dramatically, and more and more people lived long enough to reproduce successfully, often many times over. The result was an exponential pattern of growth (Figure 1.7). This pattern is often called a J curve because the ever-shorter periods between doubling and redoubling of the population cause an abrupt upward swing in the growth line when depicted on a graph.

Today, the human population is growing in most regions of the world, more rapidly in some places than in others. The reason for this growth is that currently a very large group of young people has reached the age of reproduction, and more will shortly join them. Nevertheless, the rate of global population growth is slowing. Since 1993 it has dropped from 1.7 percent per year to roughly 1.1 percent per year, which is where it stands today. If present slower growth trends continue, the world population may level off at between 7.8 billion and 10 billion before 2050. However, this projection is contingent on couples in less-developed countries having the education and economic security to choose to have smaller families and the ability to practice birth control using the latest information and technology.

In a few countries (especially Japan in Asia; and Russia and Ukraine plus Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary in Central Europe), the population is actually declining and rapidly aging, due primarily to low birth and death rates. This situation could prove problematic, as those who are elderly and dependent become more numerous, posing a financial burden on a declining number of working-age people. HIV/AIDS is affecting population patterns to varying extents in all world regions. In Africa, the epidemic is severe; as a result, several African countries have sharply lowered life expectancies among young and middle-aged adults.  11. WORLD POPULATION TO BE CONCENTRATED IN DEVELOPING NATIONS, AS TOTAL EXPECTED TO REACH 9 BILLION BY 2050

11. WORLD POPULATION TO BE CONCENTRATED IN DEVELOPING NATIONS, AS TOTAL EXPECTED TO REACH 9 BILLION BY 2050

Local Variations in Population Density and Growth

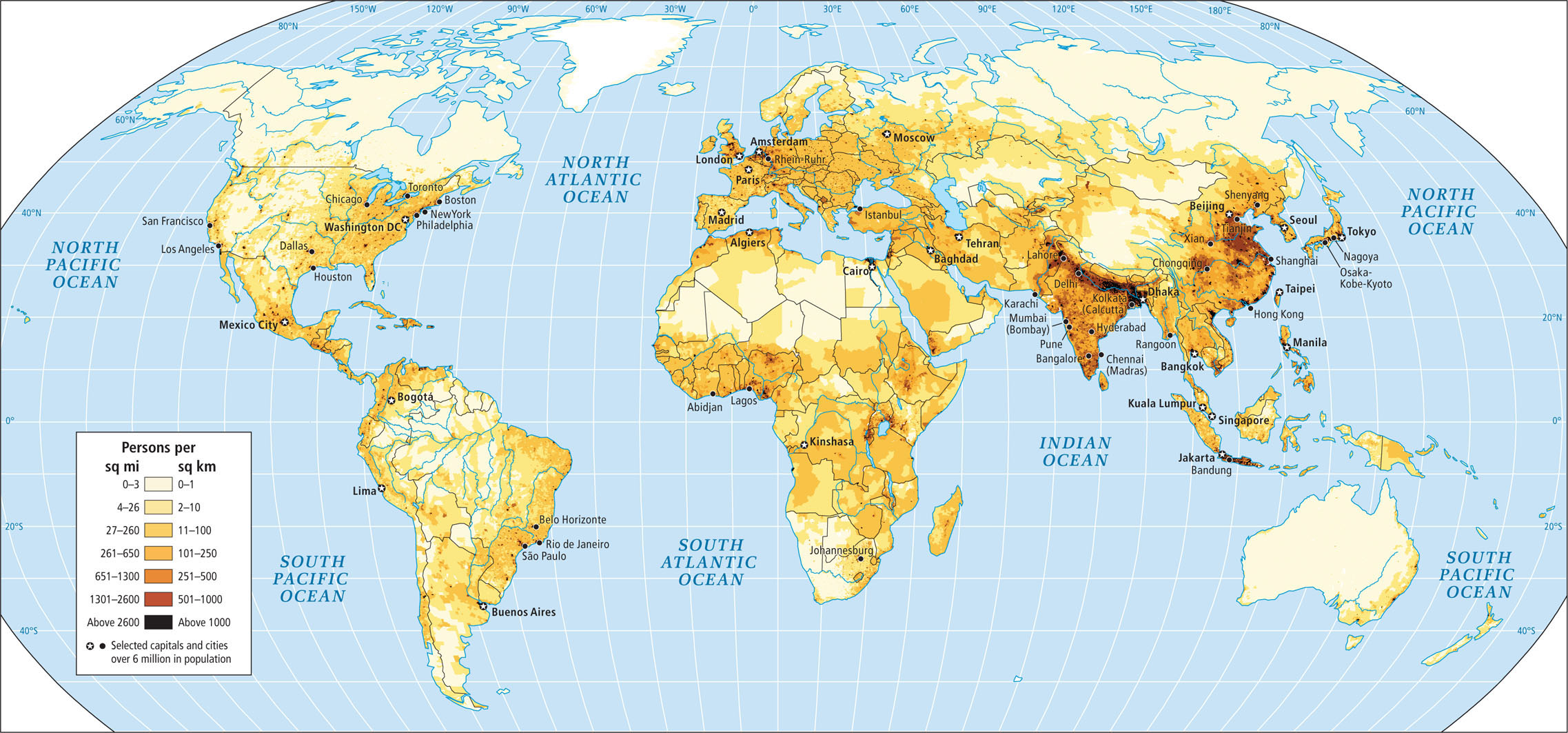

If the more than 7 billion people on Earth today were evenly distributed across the land surface, they would produce an average population density of about 121 people per square mile (47 per square kilometer). But people are not evenly distributed (Figure 1.8). Nearly 90 percent of all people live north of the equator, and most of them live between 20° N and 60° N latitude. Even within that limited territory, people are concentrated on about 20 percent of the available land. They live mainly in zones that have climates warm and wet enough to support agriculture: along rivers, in lowland regions, or fairly close to the sea. In general, people are located where resources are available.

rate of natural increase (RNI) the rate of population growth measured as the excess of births over deaths per 1000 individuals per year without regard for the effects of migration

birth rate the number of births per 1000 people in a given population, per unit of time (usually per year)

death rate the ratio of total deaths to total population in a specified community, usually expressed in numbers per 1000 or in percentages

migration the movement of people from one place or country to another, often for safety or economic reasons

total fertility rate (TFR) the average number of children that women in a country are likely to have at the present rate of natural increase

immigration in-migration (see also migration)

emigration out-migration (see also migration)

The rate of natural increase is expressed as a percentage per year. For example, in 2011, the annual birth rate in Austria (in Europe) was 9 per 1000 people, and the death rate was 9 per 1000 people. Therefore, the annual rate of natural increase was 0 per 1000 (9 − 9 = 0), or 0 percent.

For comparison, consider Jordan (in Southwest Asia). In 2011, Jordan’s birth rate was 31 per 1000, and the death rate was 4 per 1000. Thus the annual rate of natural increase was 27 per 1000 (31 − 4 = 27), or 2.7 percent per year. At this rate, Jordan’s population will double in just 29 years.

Total fertility rate (TFR), another term used to indicate trends in population, is the average number of children a woman in a country is likely to have during her reproductive years (15–49). The TFR (2011) for Austrian women is 1.4; for Jordanian women, it is 3.8. As education rates for women increase, and as they postpone childbearing into their late 20s, total fertility rates tend to decline.

Another powerful contributor to population growth is immigration (in-migration). In Europe, for example, the rate of natural increase is quite low, but the region’s economic power attracts immigrants from throughout the world. Austria was attracting immigrants at the rate of 0.03 percent of its population in 2011, while Jordan was losing population to emigration (out-migration) at the rate of 0.04 percent of the population per year. In 2010, international migrants accounted for about 85 percent of the European Union’s population growth; they were important additions to the labor force in an era of declining births. All across the world people are on the move, seeking to improve their circumstances; often they are fleeing war, natural disasters, or economic recessions; understandably, developed countries are favored destinations.

Age and Sex Structures

Age and sex structures of a country’s population reflect past and present social conditions, and can help predict future population trends. The age distribution, or age structure, of a population is the proportion of the total population in each age group. The sex structure is the proportion of males and females in each age group.

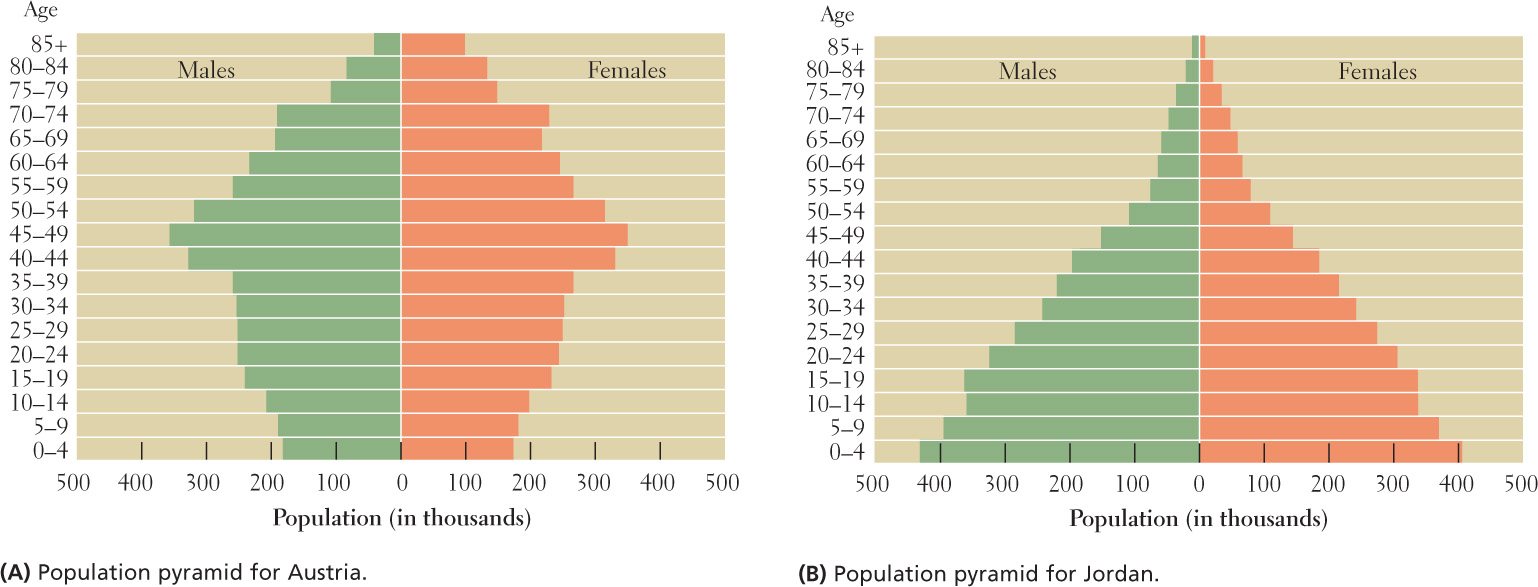

The population pyramid is a graph that depicts age and sex structures. Consider the population pyramids for Austria and Jordan (Figure 1.9). Notice that Jordan’s is a true pyramid with a wide bottom, and that the largest groups are in the age categories 0 through 14.

In contrast, Austria’s pyramid has an irregular vertical shape that tapers in toward the bottom. The base, which began to narrow rather relentlessly about 40 years ago, indicates that there are now fewer people in the youngest age categories than in the teen, young adulthood, or middle-age groups; those over 70 greatly outnumber the youngest (ages 0 to 4). This age distribution is due to two trends: many Austrians now live to an old age, and in the last several decades, Austrian couples have chosen to have only one child, or none. If these trends continue, Austrians will need to support and care for large numbers of elderly people, and those responsible will be an ever-declining group of working-age people.

Population pyramids also reveal sex imbalance within populations. Look closely at the right (female) and left (male) halves of the pyramids in Figure 1.9. In several age categories, the sexes are not evenly balanced on both sides of the line. In the Austria pyramid, there are more women than men near the top (especially in the age categories of 70 and older). In Jordan, there are more males than females near the bottom (especially ages 0 to 24).

Demographic research on the reasons behind statistical sex imbalance is relatively new, and many different explanations are proposed. In Austria, the predominance of elderly women reflects the fact that in countries with long life expectancies, women live about 5 years longer than men (a trend that is still poorly understood). But the sex imbalance in younger populations has different explanations. The normal ratio worldwide is for about 95 females to be born for every 100 males. Because baby boys on average are somewhat weaker than girls, the ratio normally evens out naturally within the first 5 years. However, in many places the ratio is as low as 80 females to 100 males, and continues throughout the life cycle. The widespread cultural preference for boys over girls (discussed in later chapters) becomes more observable as couples choose to have fewer children. Some fetuses, if identified as female, are purposely aborted; also, girls and women are sometimes fed less well and receive less health care than males, especially in poverty-stricken areas. Because of this, females are more likely to die, especially in early childhood. The gender imbalance of more males than females can be especially troubling for young adults, because the absence of females will mean that young men will find it hard to find a marriage mate.

Population Growth Rates and Wealth

Although there is a wide range of variation, regions with slow population growth rates usually tend to be affluent, and regions with fast growth rates tend to have widespread poverty. The reasons for this difference are complicated; again, Austria and Jordan are useful examples.

population pyramid a graph that depicts the age and gender structures of a political unit, usually a country

gross national income (GNI) per capita the total production of goods and services in a country in a given year divided by the mid-year population

By contrast, Jordan has a GNI (PPP) per capita of $5730 in addition to a high infant mortality rate of 23 per 1000. Much everyday work is still done by hand, so each new child is a potential contributor to the family income at a young age. There is little social welfare for elderly citizens and a much greater risk of children not surviving into adulthood. Having more children helps ensure that someone will be there to provide care for aging parents and grandparents.

demographic transition the change from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates that usually accompanies a cluster of other changes, such as change from a subsistence to a cash economy, increased education rates, and urbanization

subsistence economy an economy in which families produce most of their own food, clothing, and shelter

cash economy an economic system that tends to be urban but may be rural, in which skilled workers, well-trained specialists, and even farm laborers are paid in money

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Over the last several hundred years, global population growth has been rapid. Although growth will continue for many years, rates are now slowing in most places and in a few places growth has reversed and the population is even shrinking.

Over the last several hundred years, global population growth has been rapid. Although growth will continue for many years, rates are now slowing in most places and in a few places growth has reversed and the population is even shrinking. The circumstances that lead to lower population growth rates also lead to the overall aging of populations; these two phenomena are found nearly everywhere on Earth today, but to varying degrees.

The circumstances that lead to lower population growth rates also lead to the overall aging of populations; these two phenomena are found nearly everywhere on Earth today, but to varying degrees.