The Great Plains Breadbasket

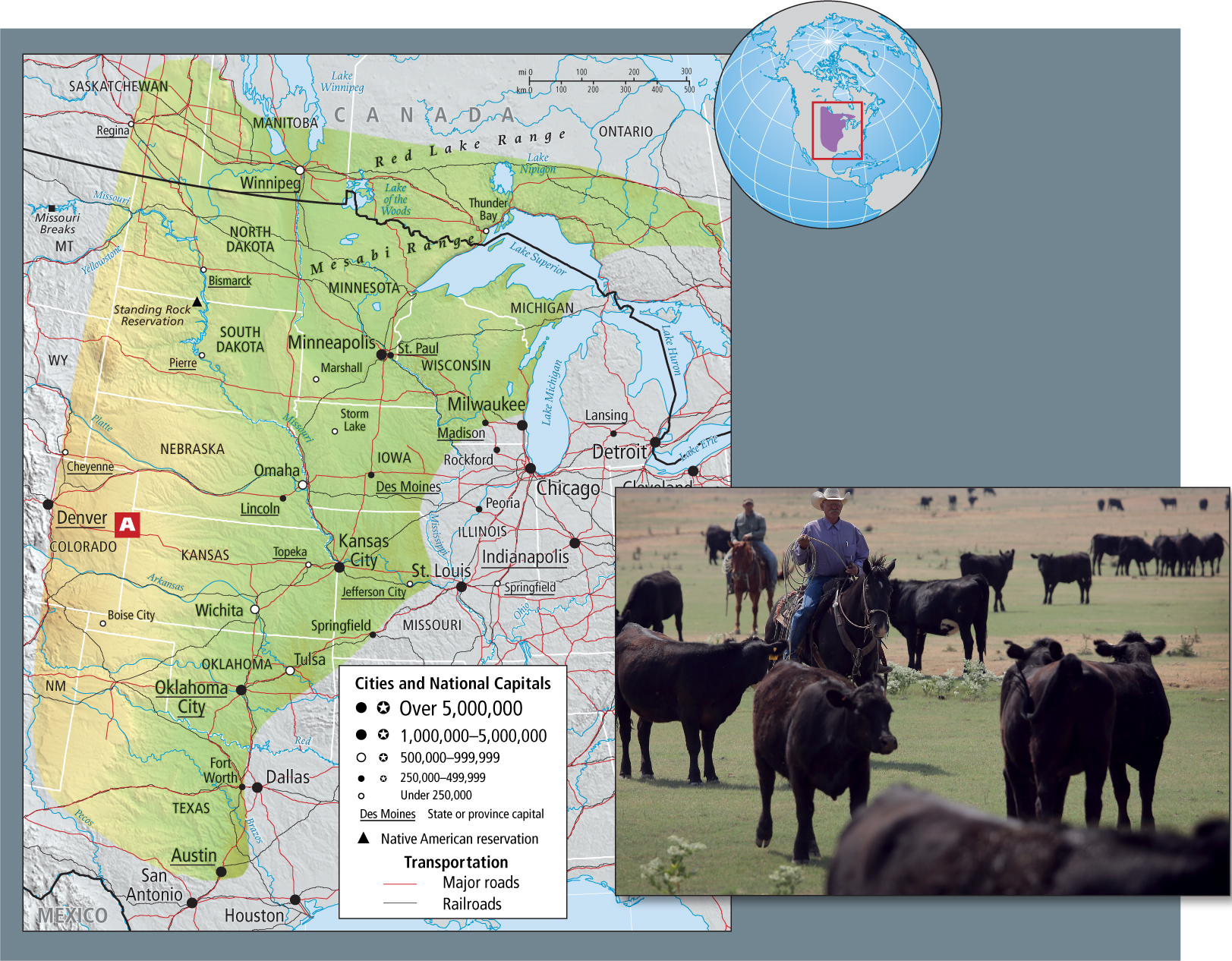

The Great Plains (Figure 2.46) receives its nickname, the Breadbasket, from the immense quantities of grain it produces—wheat, corn, sorghum, barley, and oats. Other crops include soybeans, sugar beets, sunflowers, and meat. But the Great Plains presents many challenges to agriculture, and the system as we know it may not persist.

The gently undulating prairies give the region a certain visual regularity; its weather and climate, in contrast, can be extremely unpredictable, making life precarious at times. In spring, more than a hundred tornadoes may strike across the region in a single night, taking lives and demolishing whole towns. Precipitation is unpredictable from year to year. Summers in the middle of the continent, even as far north as the Dakotas, can be oppressively hot and humid yet lacking in sufficient rainfall, while winters can be terribly cold and dry, or extremely snowy.

Adapting to the Challenges of the Great Plains

The people of the plains have learned to adapt to these challenges ever since settlers began to stake claims there in the 1860s. As people do in even drier regions in the Continental Interior, Great Plains farmers often irrigate their crops with water pumped from deep aquifers and delivered with central-pivot sprinklers that irrigate circular-shaped areas (Figure 2.47). However, to produce enough grain for one slice of bread in irrigated fields takes 10.4 gallons of water, a rate of water usage that is not sustainable (see Table 1.2). Much of the primary crop, wheat, is genetically selected to resist frost damage. Most wheat is harvested by an energy-intensive system that involves traveling teams of combines that start harvesting in the south in June and move north over the course of the summer. To select the most profitable crops and find the best time to sell them, plains farmers keep close tabs on the global commodities markets, usually with computers installed in barns, homes, or even in the cabs of the huge (and very costly) farm machines they use to work their land.

Courtesy David Boyer/National Geographic/Getty Images

113

Animal raising, the other important activity on the Great Plains, has become problematic from environmental and animal-rights perspectives (see Figure 2.46A). Rather than being herded on the open range, as in the past, cattle are now raised in fenced pastures and then shipped to feedlots, where they are fattened for market on a diet rich in sorghum and corn, but often in muddy, inhospitable pens. And like wheat, meat production uses a great deal of water in an area prone to drought. For example, to grow and process the amount of beef in one hamburger requires 640 gallons of water.

Erosion is a serious problem on the plains: soil is disappearing more than 16 times faster than it can form. Grain fields and pasture grasses do not hold the soil as well as the original dense undisturbed prairie grasses once did. Plowing and the sharp hooves of the cattle loosen the soil so that it is more easily carried away by wind and water erosion. Experts estimate that each pound of steak produced in a feedlot results in 35 pounds of eroded soil. Given the costs in soil and water, raising cattle in this region is by no means a sustainable economic activity.

Globalization Impacts in the Great Plains

Cattle and other livestock, such as hogs and turkeys, are slaughtered and processed for market in small plants across the plains by low-wage, often immigrant, labor. This is new. In the 1970s, a meatpacking job in the Great Plains provided a stable annual income of $30,000 or more, relatively high for the time. The workforce was unionized, and virtually all workers were descendants of German, Slavic, or Scandinavian immigrants who immigrated in the nineteenth century. But in the 1980s, a number of unionized meatpacking companies closed their doors. Other nonunion plants opened, often in isolated small towns in Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota. The labor is no longer local residents, but immigrants from Mexico, Central America, Laos, and Vietnam. Pay is only about $6.00 an hour, for an after-tax annual income of less than $12,000. The union work rules are gone: safety is often haphazard; working hours are long or short, at the convenience of the packing-house manager; overtime pay is rare; and those who protest may lose their jobs.

114

Many of the immigrant workers are refugees from war in their home countries, and their path to assimilation into American society is blocked by wages that are not sufficient to provide a decent life for their children. The Reverend Tom Lo Van, a Laotian Lutheran pastor in Storm Lake, Iowa, says of the Laotian families in his church that the youth are unlikely to prosper from their parents’ toil. “This new generation is worse off,” he says. “Our kids have no self-identity, no sense of belonging…no role models. Eighty percent of [them] drop out of high school.”

Changing Population Patterns and Land Use on the Great Plains

Mechanization has reduced the number of jobs in agriculture and encouraged the consolidation of ownership. Increasingly, corporations own the farms of the Great Plains. Individuals who still farm may own several large farms in different locales. They often choose to live in cities, traveling to their farms seasonally. As a result of these trends, rural depopulation is severe. Thousands of small prairie towns are dying out. Between 2000 and 2007, 60 percent of the counties in the Great Plains lost population; the area now has fewer than 6 people per square mile (2 per square kilometer). The few cities around the periphery of the region (Denver, Minneapolis, St. Louis, Dallas, Kansas City) are growing, as young people leave the small towns on the prairies.

Some suggest that European agricultural settlement on the Great Plains may be an experiment that should end. Modern agriculture, with its high demands for water and for fertile soil, has proven too stressful for the plains environments, and these days the only Great Plains rural counties with increasing populations are those with significant numbers of Native Americans. In the western Great Plains, some educated Native Americans are returning to work in newly established gambling casinos, new ranching establishments, and other enterprises. Although still only a fraction of the total plains population, the Native American population in North and South Dakota, Montana, Nebraska, and Kansas grew from 12 to 23 percent between 1990 and 2000.

Connecting Bees, Global Corn, the Northern Plains, and Almond Groves in California

Cattle ranches and grain farms still prevail in the middle and southern plains, but in the northwestern plains, many farmers have been putting their land into the Federal Conservation Reserve program, which is aimed at stopping soil erosion and saving water by paying farmers to take land out of production.

It is the return of native grasses and wildflowers that brought beekeepers and their hives to the northern plains. For some years now, beekeepers have “parked” their beehives in this area so that their bees can produce honey by feeding on the nectar and pollen of prairie wildflowers. During a few lucrative weeks in February, when the almond groves near Fresno in the Central Valley of California are in bloom, the beekeepers truck their thousands of beehives (containing as many as a billion bees) to pollinate California’s Central Valley almond flowers (Figure 2.48). California produces two-thirds of the world’s almonds; without the bees to pollinate, there would be no almonds. When the almond bloom is over, the bees need to return to their Great Plains wildflower sanctuary.

115

Here is the problem: since 2008, when corn became a commodity in high demand for making ethanol, producing corn-based sweeteners, and feeding the world’s hungry, Great Plains farmers who had their land in the Federal Conservation Reserve suddenly could make more money putting their land back into corn. They plowed up the prairie, and the bees lost at least half of the wildflower cover on which they had previously thrived.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Native Americans Lead a Revival of Sustainability on the Great Plains

Mike Faith, a Sioux trained in animal science, manages a large bison herd at Standing Rock Reservation, not far from where Sitting Bull was killed in 1890. Bison meat, which is low in cholesterol, may help control obesity, a recognized problem among Native Americans. Faith says, “Just having these animals around, knowing what they meant to our ancestors, and bringing kids out to connect with them has been a big plus.”

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Plains farmers keep close tabs on the global commodities markets, usually with computers installed in barns, homes, or even in the cabs of their huge (and costly) farm machines.

Plains farmers keep close tabs on the global commodities markets, usually with computers installed in barns, homes, or even in the cabs of their huge (and costly) farm machines. Population patterns are changing throughout the Great Plains as rural counties lose population to urban areas and local farmworkers are replaced by immigrants working at lower wages.

Population patterns are changing throughout the Great Plains as rural counties lose population to urban areas and local farmworkers are replaced by immigrants working at lower wages. Soil erosion and water depletion are serious problems and ultimately will cause significant changes in agricultural practices in this subregion.

Soil erosion and water depletion are serious problems and ultimately will cause significant changes in agricultural practices in this subregion. A combination of old and new agricultural strategies are being tried in the Great Plains.

A combination of old and new agricultural strategies are being tried in the Great Plains. The landscapes of the Great Plains change according to changing farming methods and to rising and falling global demands for certain crops, such as corn. These landscape changes are in turn linked to factors elsewhere, such as global demand for food and the production of crops—for example, almonds in the Central Valley of California.

The landscapes of the Great Plains change according to changing farming methods and to rising and falling global demands for certain crops, such as corn. These landscape changes are in turn linked to factors elsewhere, such as global demand for food and the production of crops—for example, almonds in the Central Valley of California.