The Continental Interior

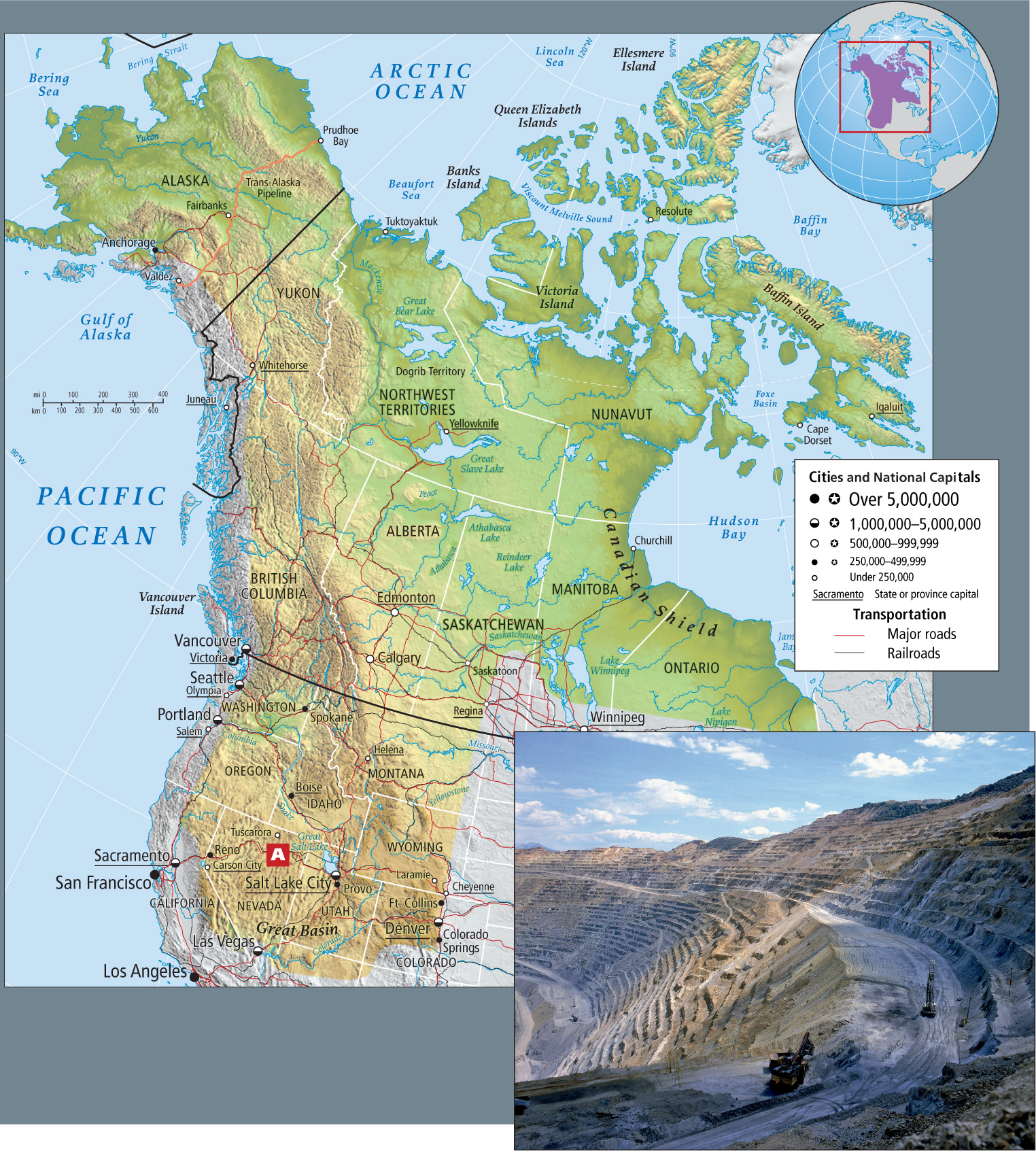

Among the most striking features of the Continental Interior (Figure 2.49) are its huge size, its physical diversity, and its very low population density. This is a land of extreme physical environments, characterized by rugged terrain, extreme temperatures, and lack of water (to gain appreciation for these characteristics, compare the map in Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.4C and the related map with Figure 2.49). These extreme physical features restrict many economic enterprises and account for the low population density (see Figure 2.34) of fewer than 2 people per square mile (1 person per square kilometer) in most parts of the region.

Courtesy Ray Ng/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Four Physical Zones

Physically, there are four distinct zones within the Continental Interior: the Canadian Shield, the frigid and rugged lands of Alaska, the Rocky Mountains, and the Great Basin. The Canadian Shield is a vast, glaciated territory north of the Great Plains that today is characterized by thin or nonexistent soils, innumerable lakes, and large meandering rivers. The rugged lands of Alaska lie to the northwest of the shield. The shield and Alaska have northern coniferous (boreal) and subarctic (taiga) forests along their southern portions. Farther north, the forests give way to the tundra, a region of winters so long and cold that the ground is permanently frozen several feet below the surface. Shallow-rooted, ground-hugging plants such as mosses, lichens, dwarf trees, and some grasses are the only vegetation. The Rocky Mountains stretch in a wide belt from southeastern Alaska to New Mexico. The highest areas are generally treeless, with glaciers or tundra-like vegetation, while forests line the rock-strewn slopes on the lower elevations. Between the Rockies and the Pacific coastal zone is the Great Basin, which was formed by an ancient volcanic mega crater. It is a dry region of widely spaced mountains, covered mainly by desert scrub and occasional woodlands.

tundra a region of winters so long and cold that the ground is permanently frozen several feet below the surface

Native Americans and First Nations

The Continental Interior has the greatest concentration of native people in North America, most of them living on reservations, as native lands are called in the United States. Because of the banishment of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the nineteenth century, only those who live in the vast tundra and northern forests of the Canadian Shield still occupy their original territories. The Nunavut, for example, recently won rights to their territory (part of the former Northwest Territory) after 30 years of negotiation. They are now able to hunt and fish and generally maintain the ways of their ancestors, although most of them now use snowmobiles and modern rifles. In September 2003, the Tłįchǫ First Nation (formerly known as the Dogrib), a Native Canadian group of 3500, reclaimed 15,000 square miles of their land just south of the Arctic Circle. The Nunavut and the Tłįchǫ, who have a strong sense of cultural heritage and an entrepreneurial streak as well, have Web sites and manage their lives and the resources of their ancestral lands—oil, gas, gold, and diamonds—with the aid of Internet communication.

Settlements

The Continental Interior is a fragile environment. It is one of the most intense battlegrounds in North America between environmentalists and resource developers.

Although much of the Continental Interior remains sparsely inhabited, nonindigenous people have settled in considerable density in a few places. Where irrigation is possible, agriculture has been expanding—in Utah and Nevada; in the lowlands along the Snake and Columbia rivers of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington; and as far north as the Peace River district in the Canadian province of Alberta (see Figure 2.47). There are many cattle and sheep ranches throughout much of the Great Basin. Overgrazing and erosion are problems, but more serious concerns include unsustainable groundwater extraction and pollution from chemical fertilizers. A further pollutant is the malodorous effluent from feedlots where large numbers of beef cattle are fattened for market. Efforts by the U.S. government to curb abuses on federal land, which is often leased to ranchers in extensive holdings, have not been very successful.

116

117

Increasing numbers of people are migrating to the Continental Interior. The many national parks in the region attract both seasonal and permanent workers and millions of tourists. Other people come to exploit the area’s natural resources. Towns such as Laramie, Wyoming, and Calgary, Alberta, have swelled with workers in the mining and fossil fuel industries. These various groups often find themselves in conflict with each other and with the indigenous people of the Continental Interior. In the United States, environmental groups have pressured the federal government to set aside more land for parks and wilderness preserves and to stop building pipelines for oil and gas transport from Alberta, Canada. Environmentalists also want to limit or eliminate activities such as mining and logging, which they see as damaging to the environment and the scenery. A switch to more recreational and preservation-oriented uses throughout the region would change, and probably lessen, employment opportunities, while the increasing numbers of visitors would place stress on natural areas, particularly on water resources.

Federal Lands

More than half the land in the Continental Interior is federally owned. Mining and oil drilling, often on leased federal land, are by far the largest industries (see Figure 2.49A). Since the mid-nineteenth century, the region’s wide range of mineral resources has supported the major permanent settlements. These mineral resources link the settlements to the global economy, but fluctuating world market prices for minerals have resulted in alternating periods of booms and busts. In recent times, the most stable mineral enterprises have been oil-drilling operations along the northern coast of Alaska. From here, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline runs southward for 800 miles (1300 kilometers) to the Port of Valdez.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Mining and oil drilling, often on leased federal land, are by far the largest industries of the Continental Interior.

Mining and oil drilling, often on leased federal land, are by far the largest industries of the Continental Interior. The Continental Interior subregion is the largest and most physically diverse in North America, with four distinct zones.

The Continental Interior subregion is the largest and most physically diverse in North America, with four distinct zones. Large numbers of Native Americans from many different tribal groups in this subregion are often in conflict with mining and logging interests as well as with the increasing number of tourists and tourism developments.

Large numbers of Native Americans from many different tribal groups in this subregion are often in conflict with mining and logging interests as well as with the increasing number of tourists and tourism developments.