Physical Patterns

The continent of North America is a huge expanse of mountain peaks, ridges and valleys, expansive plains, long winding rivers, myriad lakes, and extraordinarily long coastlines. Here the focus is on a few of the most significant landforms.

Landforms

A wide mass of mountains and basins, known as the Rocky Mountain zone, dominates western North America (see Figure 2.1D). It stretches down from the Bering Strait in the far north, through Alaska, and into Mexico. This zone formed about 200 million years ago when, as part of the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea (see Figure 1.25), the Pacific Plate pushed against the North American Plate, thrusting up mountains. These plates still rub against each other, causing earthquakes along the Pacific coast of North America.

The much older, and hence more eroded, Appalachian Mountains stretch along the eastern edge of North America from New Brunswick and Maine to Georgia. This range resulted from very ancient collisions between the North American Plate and the African Plate.

Between these two mountain ranges lies the huge central lowland of undulating plains that stretches from the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico. This landform was created by the deposition of deep layers of material eroded from the mountains and carried to this central North American region by wind and rain and by the rivers flowing east and west into what is now the Mississippi drainage basin.

During periodic ice ages over the last 2 million years, glaciers have covered the northern portion of North America. In the most recent ice age (between 25,000 and 10,000 years ago), the glaciers, sometimes as much as 2 miles (about 3 kilometers) thick, moved south from the Arctic, picking up rocks and soil and scouring depressions in the land surface. When the glaciers later melted, these depressions filled with water, forming the Great Lakes. Thousands of smaller lakes, ponds, and wetlands that stretch from Minnesota and Manitoba to the Atlantic were formed in the same way (see Figure 2.1B). Melting glaciers also dumped huge quantities of soil throughout the central United States. This soil, often many meters deep, provides the basis for large-scale agriculture but remains susceptible to wind and water erosion.

East of the Appalachians, the Atlantic coastal lowland stretches from New Brunswick to Florida. This lowland then sweeps west to the southern reaches of the central lowland along the Gulf of Mexico. In Louisiana and Mississippi, much of this lowland is filled in by the Mississippi River delta—a low, flat, swampy transition zone between land and sea. The delta was formed by massive loads of silt deposited during floods over the past 150-plus million years by the Mississippi, North America’s largest river system. The delta deposit originally began at what is now the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers at Cairo, Illinois; slowly, as ever more sediment was deposited, the delta advanced 1000 miles (1600 kilometers) into the Gulf of Mexico.

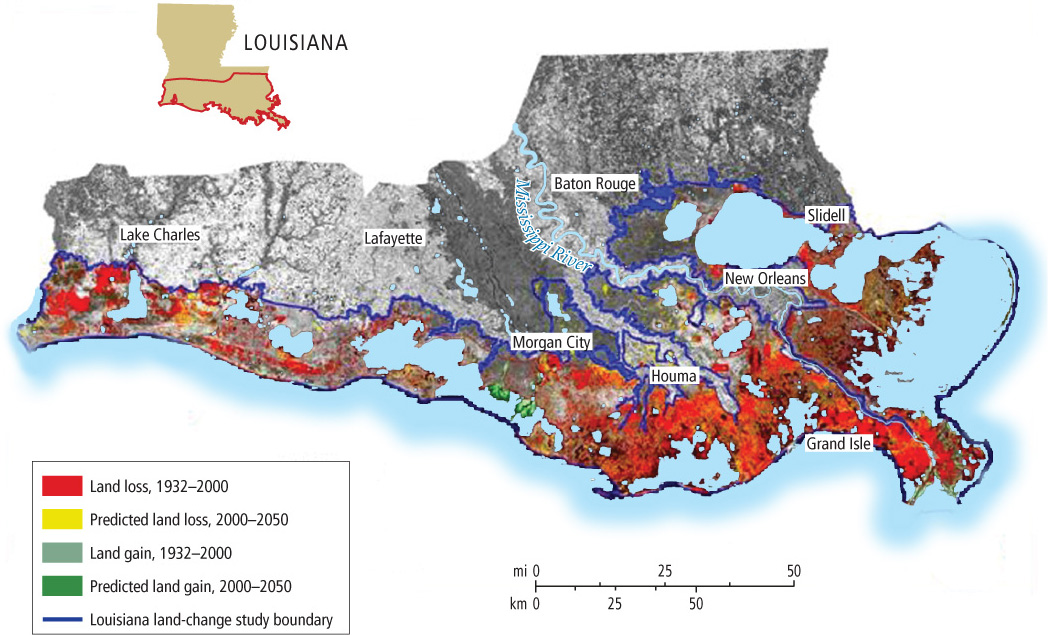

The construction of levees along the riverbanks of the Mississippi River has drastically reduced flooding. Because of this flood control, much of the silt that used to be spread widely across the lowlands during floods is being carried to the extreme southern part of the Mississippi delta, where it now drops off the continental shelf and falls into the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico. In the absence of this silt, the rest of the southern Mississippi River delta is now sinking, a process known as subsidence (Figure 2.3). As the land sinks, salt water from the Gulf intrudes inland, killing fresh-water–adapted plants and destroying swamps and wetlands.

Climate

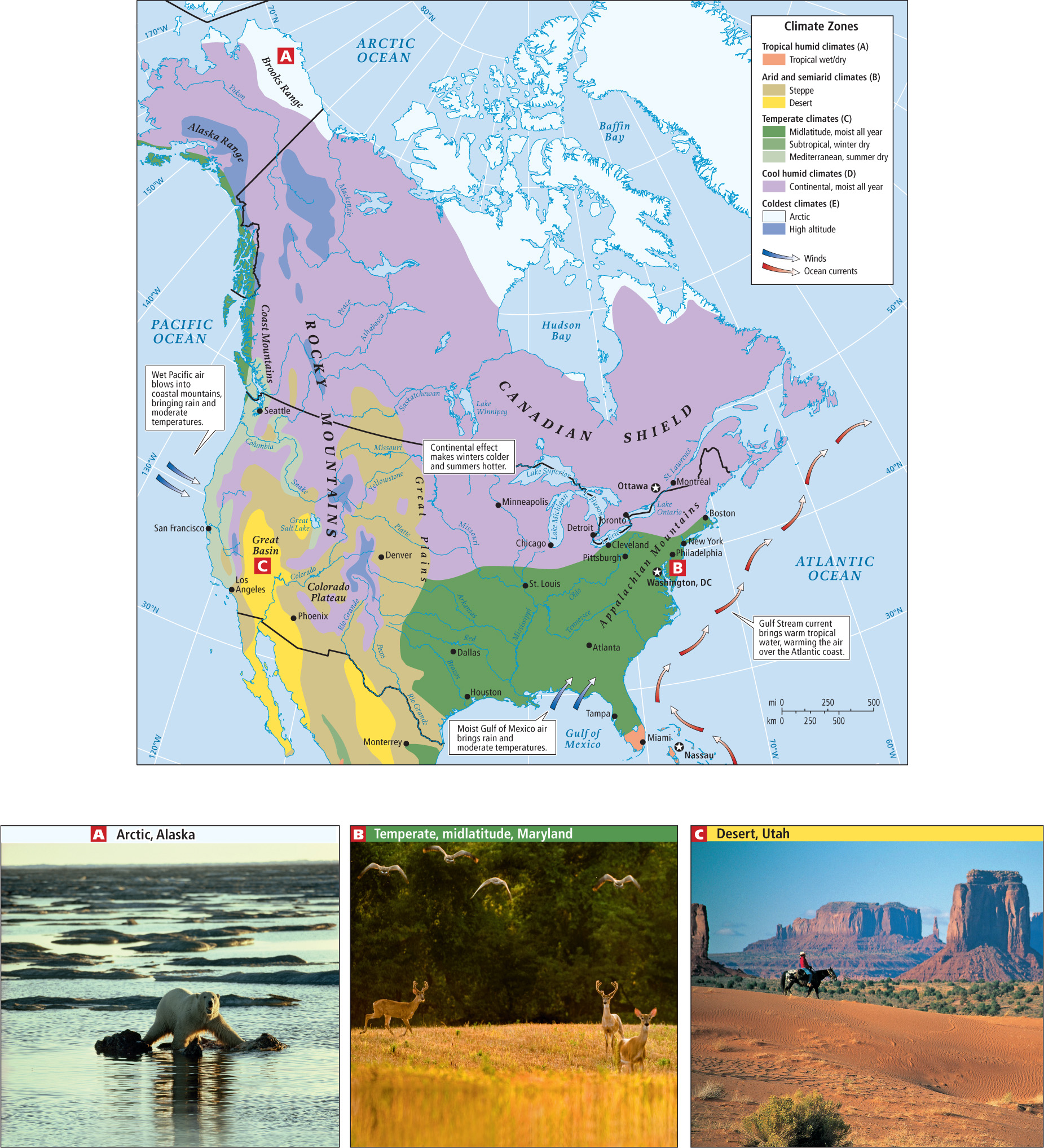

The landforms across this continental expanse influence the movement and interaction of air masses and contribute to its enormous climate variety (Figure 2.4). Along the southern west coast of North America, the climate is generally mild (Mediterranean)—dry and warm in summer, cool and moist in winter. North of San Francisco, the coast receives moderate to heavy rainfall. East of the Pacific coastal mountains, climates are much drier because as the moist air sinks into the warmer interior lowlands, it tends to hold its moisture (see Figure 1.29A). This interior region becomes increasingly arid as it stretches east across the Great Basin (see Figure 2.4C) and Rocky Mountains. Many dams and reservoirs for irrigation projects have been built to make agriculture and urbanization possible. Because of the low level of rainfall, however, efforts to extract water for agriculture and urban settlements are exceeding the capacity of ancient underground water basins (aquifers) to replenish themselves.

aquifers ancient natural underground reservoirs of water

On the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains, the main source of moisture is the Gulf of Mexico. When the continent is warming in the spring and summer, the air masses above it rise, sucking in warm, moist, buoyant air from the Gulf. This air interacts with cooler, drier, heavier air masses moving into the central lowland from the north (see Figure 2.4A) and west, often creating violent thunderstorms and tornadoes. Generally, central North America is wettest in the eastern (see Figure 2.4B) and southern parts and driest in the north and west (see Figure 2.4C). Along the Atlantic coast, moisture is supplied by warm, wet air above the Gulf Stream—a warm ocean current that flows north from the eastern Caribbean and Florida, which follows the coastline of the eastern United States and Canada before crossing the north Atlantic Ocean.

62

The large size of the North American continent creates wide temperature variations. Because land heats up and cools off more rapidly than water, temperatures in the interior of the continent are hotter in the summer and colder in the winter than in coastal areas, where temperatures are moderated by the oceans.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

North America has two main mountain ranges, the Rockies and the Appalachians, separated by expansive plains through which run long, winding rivers.

North America has two main mountain ranges, the Rockies and the Appalachians, separated by expansive plains through which run long, winding rivers. The size and variety of landforms influence the movement and interaction of air masses, creating enormous climatic variation. Because land heats up and cools off more rapidly than water, temperatures in the interior of the continent are higher in the summer and colder in the winter than in coastal areas.

The size and variety of landforms influence the movement and interaction of air masses, creating enormous climatic variation. Because land heats up and cools off more rapidly than water, temperatures in the interior of the continent are higher in the summer and colder in the winter than in coastal areas.