Human Patterns over Time

In prehistoric times, humans came from Eurasia via Alaska, dispersing to the south and east. Beginning in the 1600s, waves of European immigrants, enslaved Africans, and their descendants, spread over the continent, primarily from east to west. Today, immigrants are coming mostly from all of Asia and from Middle and South America. They are arriving mainly in the Southwest and West, where they remain concentrated. In addition, internal migration is still a defining characteristic of life for most North Americans, who are among the world’s most mobile people. On average they move nearly 12 times in a lifetime.

The Peopling of North America

Recent evidence suggests that humans first came to North America from northeastern Asia at least 25,000 years ago or perhaps earlier, most arriving during an ice age. At that time, the global climate was cooler, polar ice caps were thicker, and sea levels were lower. The Bering land bridge, a huge, low landmass wider than 1000 miles (1600 kilometers), connected Siberia to Alaska. Bands of hunters crossed by foot or small boats into Alaska and traveled down the west coast of North America.

The Original Settling of North America

By 15,000 years ago, humans had reached nearly to the tip of South America and had spread deep into that continent. By 10,000 years ago, global temperatures began to rise. As the ice caps melted, sea levels rose and the Bering land bridge was submerged beneath the sea.

Over thousands of years, the people settling in the Americas domesticated plants, created paths and roads, cleared forests, built permanent shelters, and sometimes created elaborate social systems. About 3000 years ago, corn was introduced from Mexico (into what is now the U.S. southwestern desert) along with other Mexican domesticated crops, particularly squash and beans. These food crops are thought to be closely linked to settled life, resulting in North America’s prehistoric population growth.

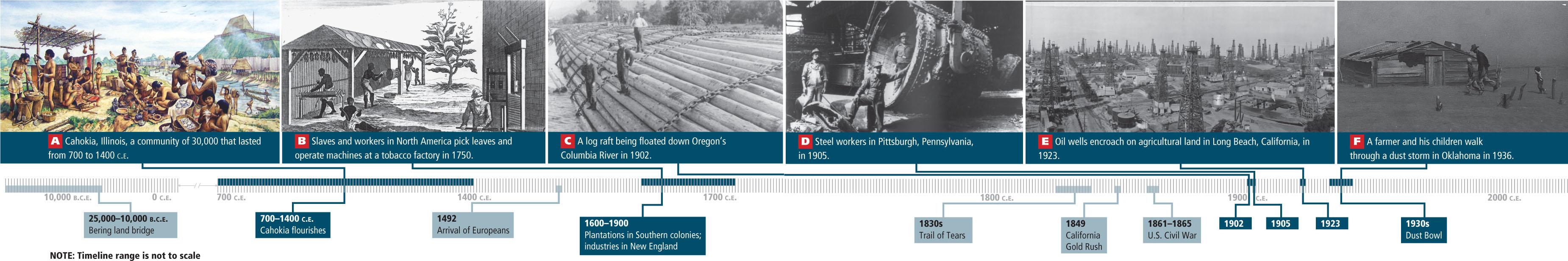

These foods provided surpluses that allowed some community members to engage in activities other than agriculture, hunting, and gathering, making possible large, city-like regional settlements. For example, by 1000 years ago, the urban settlement of Cahokia, including suburban settlements (in what is now central Illinois across the Mississippi from St. Louis), covered 5 square miles (12 square kilometers) and was home to an estimated 30,000 people (see Figure 2.9A). Here people could specialize in crafts, trade, or other activities beyond the production of basic necessities.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of North America, you will be able to answer the following questions.

Question

F5/x1zvsYSqu7FPWFAUJbUhvpdkRlnWzsmfaOCnkkM2ztbMU1yLsVuhXK4mXXIwdYJSd6bVMGI4qnfZWiDtVbkhDbQSR0Nw0wZxfXmWbvyeFsev1JhDFLE3j3UH1xNM7urrsgvBjQaYLTCLJGxswOMFgw1MrUjnR+u+F/HLRObzEkVS6vkW2QgYLckv293PBuBh8fHn+gJHGkmG5DKTKo0MP3AwrJ5cvCeigQXZTvaaKg5AOLFkkz2zGLV8yid6VpgKaBagMH6Xqdw7qfz/9eSMVZS9yh3tpvKzY0ZxcsgDH7ZnIo4RK4COAJtFenhXkDU0q8E56b7iyc8cxIX1qnlbrGqdCPmBeN+BkPg6E9CD6ZwJBbSjcS2iC6LSsRK+/1UY9yRf2h/XFuxHuiSgICOUINUac/Xpwif6Bz/GULpoLDU8jm0JPZXbdDWMMeD+uWdYbuUTwVyjsZBIh51iHwxhGK/dHIGr4DBtboqffoo6rVZy+yltU4c4ugHnag+jlDUEs9dyzMBHF0tfuVJ+TgOvYtx0c8PMoTqk9IgNr+eqMxMXRrRfXVPCKnBtPOfTazyVbDamnXxtnoahT2Yd45pBwfNWU68KZ9jfSoaeC4oBA5MuAK+HGBjyESVVZChnznDQhhOLDLlOamGTf4OLNste9DQyUdx7ZDTPrFM5eb87A1qz5/fmwJDmZukrNz5ewVE4dsU5WwTzjIKALfMsW7748abW8lvOFql5vqrWcss25OQXXGO3LuVRrkKGeNL5adSXt4sfBM/PxDm5NmOoQpF1Zn7UAWDfLWt0WLvo3R2NJuGsrfaGDG063I1Y2zD/orli9gqsIBqvEMVBAYN2PSlFxQ1c+i5ZXlCEPRfES6Q8=Question

qPcjx0sL8nJCQ5/JRF0Wp9vc7E8IwrGdWVYW3nRF6swt+apDGLLocUSUU8eEz+U9oumS5IVzC4frJrDqi03tcMPcJA0nxYn5nfc9PsEQjpWhBfkUzswOfpQ2jkXmbtqDTtUraSYTF8CS/h4XaMYr03S81RxS8DuPNXBYsYKJV7hMLv8EV/lFsJz5y1Ky+Bfm2uK16HVeQoTEnjAbPkyDtPzTHy3/TbPRx2ZtsOog/Ss3WwL8AFX+JdCtiDsK2Jna63TVomueodZubHpLq8TjivzmZxlqQ5XtchXwstK68qC9SDcHcKZ87IRzUYve9x/1ZjqThg/WzI+YmIYr/B7WzhQ77Z17A85bLi7mPbVNjCxrku38E8XyDONBKFUIogwMoL42Fhgwn5ekCG4hf1UeOTrTDcYwQ/BlcIfrv51SSnZilqK6Ct9lJ22Rhiieape2ihUjOfsiGkz8KjRPSI8HcvzORGV7RuluH1lysbh5+dFGnhwcDr9523IJ9kQep2wSmSjRy9bmt48m/aMCnrd/O5TofzkQ09EH4yXgsl8eLgqNvM3/isyZ9O9cLAFbyJFcOQ5Vj4f84OshJDPJ2p1I3Hq2DaYU55Ns3s2lzRRAEjw3o/Z8G/KNahmFXwLUugZ7ACxwHrDgCGZZlCUpQGPWcQXMn+Tb1zPGhO6845fZw2Washz+603p+WfXgkRDjHwNkyWEtu9w9Dah2fqhLiB4sJuBYs1ZjKKzcWvFQnVfGZR/VU+YmJ02o+m8JtdLzNNRGMMRfgkaCk/1a1OMMJfL8GBIGIif1ylguK3I8MXur6qRePoyTpfjXRFPRWhVjX/H4OZ+jfDqzjBOdSHwH1zjqjILtSlY1+TbRITkCQdaOo9zT667pms69m1UZNYe218SN4vqlS6OFf9Ceww+hDAY/gIEdbewN/alG6P8ocqG+lLtxhVXptt0unLtR5Pb0WdNlDRk3dN3gAoj70nOhND2c1Jdh59wq/mZCQJS0X+DVlihY4CzPzdjII/foww=Question

6eaB2BzdTnSk+2b4QJWmCq0DQeMGwhscLZMrlbBUhcfuMbil5AI/lkfZ85hyHkDOT2UPrwozRGzOZzFfxDutW92Ne9ShXzP6KAn/z1DJX6sfzn40c9H767i7vf9OvH19I17ftXXaxRrstpcq2oLuTOayN9SM3eqgHdK2mMixeo0qRZgeE0AbMmEg8KmAHn92fjSqKpjPhDXBYrtamisacSDp8j97QO/bjZxkdwDQpJwcznY9rIlQKRYUnVxHG/W3aSdJTGKacZVv5Rce75gGDjLgOhuVoSztW6MFA5LPVWgcdQt+0ZniBM2cXuhIJKMlZgHr7+gLx9umhPTUCTJ84W0LJ5071m6MNqqmi5hmTlPD2+k9d6PWUML9xrssPBEq55kxGXPlHPhdl/1wlRwCAjsB0c2mAcdTBNnyxsLfM1xIhS7sfXAHRdOc1X4hIdQHD/XFtSFYsNyhvIHVFes8DKu0qPfCGqQgo8s1gGnJJ4j4qZwSKJFHbhowrrrJR8nb1vY1c4DTVvi5/jb4Y+I0qgFzTfEiUyqY/oGbg83Bz+Q6pDWCPoxslGgcxNMb5Uzl8fvfChGzsC+7lPqBG4rMKReXAQYwfoagqCdunGZHvlZ1BwBiUNWAm7mgoBbkv1jb/WrE6yDTHvwXiKd4CmS5AwBpYA4lvk/xZItWgEhk6Edo88gOTsT9TN/x5AUKWvqZ8/jz22toMNXwoovsipYDcpwQ+yUstYa3Question

vBK4n6611P83fUnN4YTxJ7g+SSi/42kzYZ1qhnOapB7KXbJ0j5bI/zEvUsuxoBrkmJvGOSjeidDfAQrNyc/dnP5RT5+zpK8FIG8NrbggSBTRtPsKa/QtpdFq35kNUYQiLmWT3WIJrSmwopd8ExwYMUOXnTu7YfLwpdsIX7myNsMwOWZrAw5Us0Nh/O89BDmNOpvstBQwwjS/8a+oXZ2r/UPIxVfe2XUvpWUO9uPFUc7r7Z9QnXGpj5YquPFCA7xRlVEhsVjh7O6LiErbK+A4L5zFU9d1jESORBUWOkTWqJ5BgyZO7S0mK/WszHe38kTyPDagAwC2nwutvkYQc10YX8AWDS9CVMSCqyrzvXVJEzuppQeNdSehUUPeUNKOPXIE9r/HaInRQxRNQG3WBSZPNH0eMShShPXLrtZTs5A+I/Mp4gcVsAM3qAj2T5YoWAnpi+3CbY8XQ4zw/18Ap2KUIHeXsUxye9DpX548FmpYMp5n2ia0Ymcc3S3Uk0sm4jgm3nMglatK6LF4AYMV+7PgmHdiNWXQ1Ke7AU+5zG/C8Xwe2eKXSSHbpIybYB0aYZFmXxJIbMta21O7Ct/94/5Q+43xCI/r7OE7p982i1Y+368dJu+7edYBaIlaY5FR5SKXq4wunGfI8lYiNbk2CuEjrUTHBudY7etVndDT+TVT6GmDetIi69MIXfEv1xecrizGT3y89Dqxaa8=Question

kGn2YaRL0Z/7WCgT8weBUvn5CKgJCJcRd0A9qGmFfIS1RUwwbX+CHgirSfR01CDpdhMUfb8wypi5nh0XyTlzcPrT3i/R79B6XJ1pypv5pTpjNqpv0bx3xCign8LQ9iV4YVZSaFNlGT4/BBfzVkRm5qGF9sQ4G5+w6kKbz5Pq7W7pY0fK9cvVmYL/YI+oqNNcckDwTxwh+R6oOY4Xu+mlE6HsaTVU6F0H4bxn4EoH08pK0FYOSrW2MytKurDjOvXIF4Sc6h3SdloC7wdjm9/Naz7rmsQSzkbgw8JZOe9b+NJDlvEBy16LuOpn7PRSbasWgoc23SlyYKL4AKf3kz825ECA6TxUGnFw3H27jnJ3PNrMYGCqSPG7YkH4Iah+RFYmWqKA9gFUD21Kx+iLN2fuHHr1iMw7o4pcQR9yh26xHKbidAGc06E1+EsKMGdhVxnNrpO3EKGa2t21M6d2uRLOPLJztng5kps6CM11p86y2JKwBja8flkWlcKC8E4d9xn2j8e3MlnjHIJTUna2O5BI7ObRRLkzQeFWfMU4d6QfRYAXfjdx6GNF8/OhX2oBQUHIQuestion

IX/P2470YyEeYEwlxtcjXOAZMdEaDIPYMF8WGSgwGjbzJMX3b7yDtx9oIbVeRvrbPi216Cr6B9e3FtbuoH7MEfR6Hvf4ZJ6bcOzBe0ZH5BiiycEXtFAgwkDZTg6hla0wbKwkrfDItTIv26VyBmboP/Zq+SyLLGsOk3KY+P8T5FzcOac6pnovZwjeiH/9CyJegRckd+fwoEArixG8mJDDesiRx0lqJDS58hBqoEL9PnjXcwkQHgy6jfHWBWc+h+s0js5vrkjFGI/5hZLnp4seqwQzpjEeWxSyc+86IY1tZXUNIaQAtWFNKt3ZRWw1XgeAEIY/FImvzrri5lZ05oPbDGssy/l8WlCBvnximlNUlHNlib89Tz7fvor6jbHWyPS5TTZDBJ1G2BwSFYjDUKSLvDKMfnKuFzzx0of54nbzrR8PTGI0ecLN2SI/DjRdJG8TvyaKNlzmwRAqyNBGkH+3p1BdchoyClTknlNqqf+9GVx0XksDNnMkHWwAWlfvMInPex6BW31sbr286y6ZSOHlJH2I0xWUxHQfP5b0O3ppdY6aavLj5tT20kBqkvlRqXLiXTnFhs5ma08PLaPWTNEmiZ6bqMlktBnXOGp6BaSCyCUJLOYY0/KJijJL1NscP7NI/lXyw5JazO8y1pLuGBIiKDjTwCbAfIlR6yutAUTTduS8CQW69OajD8+tK3B/kJieKMzKXRNL5d2TSol1FmZ57cSCRrlGYZPgAsua00m/YSSNn0XCmrQqnEVf1bAJDB5bXVto8O/KNLKLJCkk425olLxTJVkJWjRHL2wEV5bRhhIFEBFEErMAKpB9xdWn70ATtTZLZR8h+n71H0AANpfBTJQhUd2EwwD9The Arrival of the Europeans

North America was completely transformed by the sweeping occupation of the continent by Europeans. In the sixteenth century, Italian, Portuguese, and English explorers came ashore along the eastern seaboard of North America, and the Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto made his way from Florida deep into the heartland of the continent in the 1540s. In the early seventeenth century, the British established colonies along the Atlantic coast in what is now Virginia (1607) and Massachusetts (1620). The Dutch explored the Atlantic seaboard looking for trading opportunities, and the French explored the northern interior of the continent, entering via the St. Lawrence River. Over the next two centuries, colonists and settlers from northern Europe, assisted by enslaved Africans, built villages, towns, port cities, and plantations along the eastern coast. By the mid-1800s, they had occupied most Native American lands into the central part of the continent.

71

Disease, Technology, and Native Americans

The rapid expansion of European settlement was facilitated by the vulnerability of Native American populations to European diseases. Having long been isolated from the rest of the world, Native Americans had no immunity to diseases such as measles and smallpox. Transmitted by Europeans and Africans who had built up immunity to them, these diseases killed up to 90 percent of Native Americans within the first 100 years of contact. It is now thought that diseases spread by early expeditions, such as De Soto’s into Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Arkansas, so decimated populations in the North American interior that fields and villages were abandoned, the forest grew back, and later explorers erroneously assumed the land had never been occupied.

Technologically advanced European weapons, trained dogs, and horses also took a large toll. Often the Native Americans had only bows and arrows. Some Native Americans in the Southwest acquired horses from the Spanish and learned to use them in warfare against the Europeans, but their other technologies could not compete. Numbers reveal the devastating effect of European settlement on Native American populations. Roughly 18 million Native Americans lived in North America in 1492. By 1542, after just a few Spanish expeditions, only half that number survived. By 1907, slightly more than 400,000, or a mere 2 percent, remained.

The European Transformation

European settlement erased many of the landscapes familiar to Native Americans and imposed new ones that fit the varied physical and cultural desires of the new occupants.

The Southern Settlements

European settlement of eastern North America began with the Spanish in Florida in the mid-1500s and the establishment of the British colony of Jamestown in Virginia in 1607. By the late 1600s, large plantations in the colonies of Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia were cultivating cash crops such as tobacco and rice.

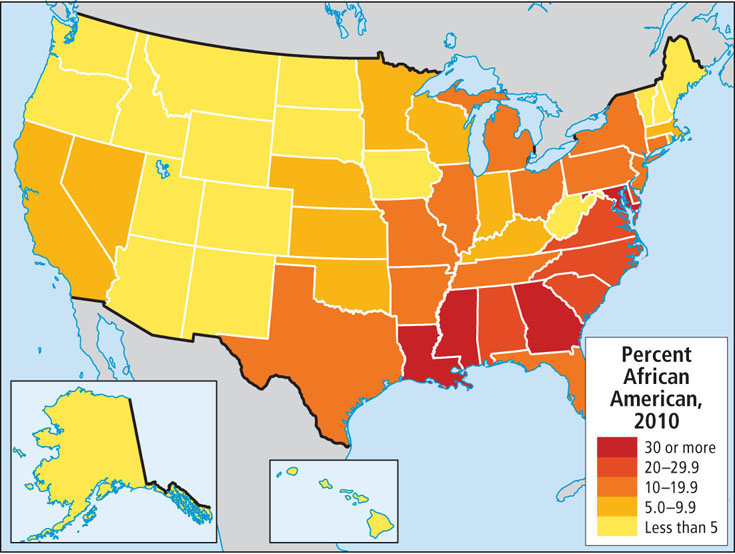

To secure a large, stable labor force, Europeans brought enslaved African workers into North America, beginning in 1619. Within 50 years, enslaved Africans were the dominant labor force on some of the larger Southern plantations (see Figure 2.9B). By the start of the Civil War in 1861, slaves made up about one-third of the population in the Southern states and were often a majority in the plantation regions. North America’s largest concentrations of African Americans are still in the southeastern states (Figure 2.10).

The plantation system concentrated wealth in the hands of a small class of landowners, who made up just 12 percent of Southerners in 1860. Planter elites kept taxes low and invested their money in Europe or the more prosperous northern colonies, instead of in infrastructure at home. As a result, the road, rail, communication networks, and other facilities necessary for economic growth were not built.

infrastructure road, rail, and communication networks and other facilities necessary for economic activity

More than half of Southerners were poor white farmers. Both they and the general slave population lived simply, so their meager consumption did not provide a demand for goods. Hence, there were few market towns and almost no industries. Plantations tended to be self-sufficient and generated little multiplier effect. Enterprises like small shops, garment making, small restaurants and bars, small manufacturing, and transportation and repair services that normally “spin off” from, or serve, main industries developed only minimally in the South. Antagonism between the weak southern economy and the stronger, more diversified northern economies was a main cause of the Civil War (1861–1865), perhaps equal to the abolition movement to free enslaved Africans and their descendents. After the war, while the victorious North returned to promoting its own industrial development, the plantation economy declined, and the South sank deeply into poverty. The South remained economically and socially underdeveloped well into the 1970s.

The Northern Settlements

Throughout the seventeenth century, relatively poor subsistence farming communities dominated the colonies of New England and southeastern Canada. There were no plantations and few slaves, and not many cash crops were exported. What exports there were consisted of raw materials like timber, animal pelts, and fish from the Grand Banks off Newfoundland and the coast of Maine. Generally, farmers lived in interdependent communities that prized education, ingenuity, self-sufficiency, and thrift.

By the late 1600s, New England was implementing ideas and technology from Europe that led to the first industries. By the 1700s, diverse industries were supplying markets in North America and the Caribbean with metal products, pottery, glass, and textiles. By the early 1800s, southern New England, especially the region around Boston, became the center of manufacturing in North America. It drew largely on young male and female immigrant labor from French Canada and Europe.

The Mid-Atlantic Economic Core

The colonies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland eventually surpassed in population and in wealth New England and southeastern Canada. This mid-Atlantic region benefited from more fertile soils, a slightly warmer climate, multiple deepwater harbors, and better access to the resources of the interior. By the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, the mid-Atlantic region was on its way to becoming the economic core, or the dominant economic region, of North America. Port cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore prospered as the intermediary for trade between Europe and the vast American Continental Interior.

economic core the dominant economic region within a larger region

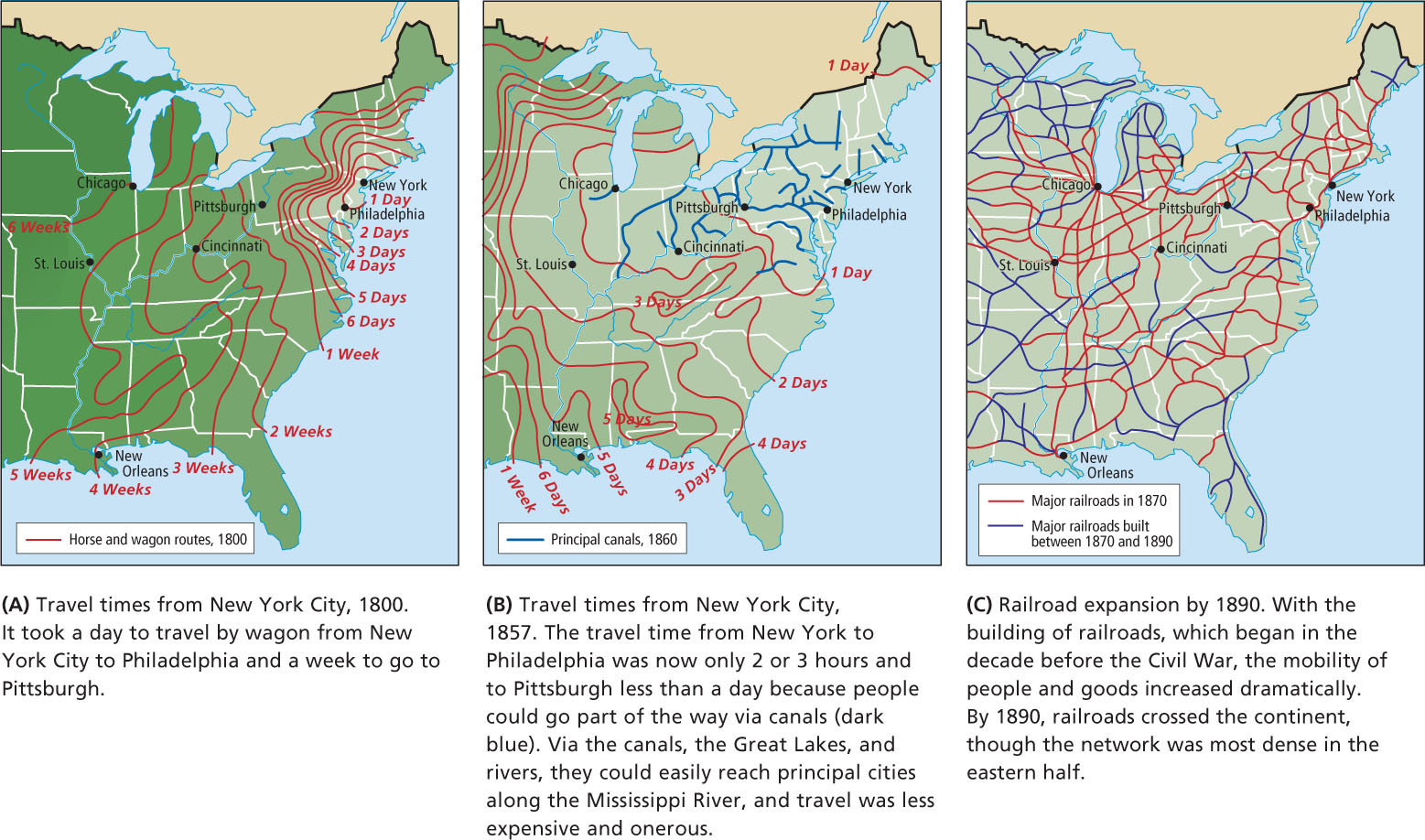

In the early nineteenth century, both agriculture and manufacturing grew and diversified, drawing immigrants from much of northwestern Europe. As farmers became more successful, they bought mechanized equipment, appliances, and consumer goods made in nearby cities. By the mid-nineteenth century, the economy of the core was increasingly based on the steel industry, which diffused westward to Pittsburgh and the Great Lakes industrial cities of Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago. The steel industry further stimulated the mining of deposits of coal and iron ore throughout the region and beyond. Steel became the basis for mechanization, and the region was soon producing heavy farm and railroad equipment, including steam engines.

72

By the early twentieth century, the economic core stretched from the Atlantic to St. Louis on the Mississippi (including many small industrial cities along the river, plus Chicago and Milwaukee), and from Ottawa to Washington, DC. It dominated North America economically and politically well into the mid-twentieth century. Most other areas produced food and raw materials for the core’s markets and depended on the core’s factories for manufactured goods (see Figure 2.9D).

Expansion West of the Mississippi and Great Lakes

The east-to-west trend of settlement continued as land in the densely settled eastern parts of the continent became too expensive for new immigrants. By the 1840s, immigrant farmers from central and northern Europe, as well as European descendants born in eastern North America, were pushing their way beyond the Great Lakes and across the Mississippi River, north and west into the Great Plains of Canada and the United States (Figure 2.11).

The Great Plains

Much of the land west of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River was dry grassland or prairie. The soil usually proved very productive in wet years, and the area became known as North America’s breadbasket. But the naturally arid character of this land eventually created an ecological disaster for Great Plains farmers. In the 1930s, after 10 especially dry years, a series of devastating dust storms blew away topsoil by the ton. This hardship was made worse by the widespread economic depression of the 1930s. Many Great Plains farm families packed up what they could and left what became known as the Dust Bowl (see Figure 2.9F), heading west to California and other states on the Pacific Coast.

73

74

The Mountain West and Pacific Coast

Some Europeans skipped over the Great Plains entirely, alerted to the possibilities farther west. By the 1840s, they were coming to the valleys of the Rocky Mountains, to the Great Basin, and to the well-watered and fertile coastal zones of what was then known as the Oregon Territory and California. News of the discovery of gold in California in 1849 created the Gold Rush, which drew thousands with the prospect of getting rich quickly. The vast majority of gold seekers were unsuccessful, however, and by 1852 they had to look for employment elsewhere. Farther north, logging eventually became a major industry (see Figure 2.9C).

The extension of railroads across the continent in the nineteenth century facilitated the transportation of manufactured goods to the West and raw materials and eventually fresh produce to the East. Today, the coastal areas of this region, often called the Pacific Northwest, have booming, diverse, high-tech economies and growing populations. Perhaps in response to their history, residents of the Pacific Northwest are on the forefront of so many efforts to reduce human impacts on the environment that the region has been nicknamed “Ecotopia.”

The Southwest

People from the Spanish colony of Mexico first colonized the Southwest in the late 1500s. Their settlements were sparse. As immigrants from the United States expanded into the region, many interested in what became a booming cattle-raising industry, Mexico found it increasingly difficult to maintain control. By 1850, nearly the entire Southwest was under U.S. control.

By the twentieth century, a vibrant agricultural economy had developed in central and southern California; irrigated agriculture was made possible by massive government-sponsored water-movement projects. The mild Mediterranean climate made it possible to grow vegetables almost year-round. With the advent of refrigerated railroad cars, fresh California vegetables could be sent to the major population centers of the East. Southern California’s economy rapidly diversified to include oil (see Figure 2.9E), entertainment, and a variety of engineering- and technology-based industries.

European Settlement and Native Americans

As settlement relentlessly expanded west, Native Americans (called First Nations people in Canada) living in the eastern part of the continent, who had survived early encounters with Europeans, were occupying land that European newcomers wished to use. During the 1800s, almost all the surviving Native Americans were either killed in one of the innumerable skirmishes with European newcomers, absorbed into the societies of the Europeans (through intermarriage and acculturation), or forcibly relocated west to relatively small reservations with few resources. The largest relocation, in the 1830s, involved the Choctaw, Seminole, Creek, Chickasaw, and Cherokee of the southeastern states. These people had already adopted many European methods of farming, building, education, government, and religion. Nevertheless, they were rounded up by the U.S. Army and marched to Oklahoma, along a route that became known as the Trail of Tears because of the more than 4000 who died along the way.

As Europeans occupied the Great Plains and prairies, many of the reservations were further shrunk or relocated onto even less desirable land. Today, reservations cover just over 2 percent of the land area of the United States.

In Canada the picture is somewhat different. Reservations now cover 20 percent of Canada, mostly due to the creation of the Nunavut Territory in 1999 in the far north (now known simply as Nunavut) and the ceding of Northwest Territory land to the Tłįchǫ First Nation (also known as the Dogrib) in 2003 (see Figure 2.1 map). These Canadian First Nations stand out as having won the right to legal control of their lands. In contrast to the United States, it had been unusual for native groups in Canada to have legal control of their territories.

After centuries of mistreatment, many Native American and First Nations people still live in poverty, and as in all communities under severe stress, rates of addiction and violence are high, especially in the United States. However, in recent decades some tribes have found avenues to greater affluence on the reservations and territories by establishing manufacturing industries; developing fossil fuel, uranium, and other mineral deposits under their lands; or opening gambling casinos. One measure of this economic resurgence is population growth. Expanding from a low of 400,000 in 1907, the Native American population now stands at approximately 6 million since 2010 in the United States, less than 2 percent of the population. In Canada, First Nations people account for 1,172,785 people, or 3.8 percent of the population.

The Changing Regional Composition of North America

The regions of European-led settlement still remain in North America, but they are now less distinctive. The economic core region is less dominant in industry, which has spread to other parts of the continent. Some regions that were once dependent on agriculture, logging, or mineral extraction now have high-tech industries as well. The West Coast, in particular, has boomed with a high-tech economy and a rapidly growing population that includes many immigrants from Asia and Middle and South America. The West Coast also benefits from trade with Asia, which now surpasses trade with Europe in volume and value.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

By the late 1600s, New England was implementing ideas and technology from Europe, which led to some of the first industries in North America.

By the late 1600s, New England was implementing ideas and technology from Europe, which led to some of the first industries in North America. The push to settle the Great Plains, the Mountain West, and the Pacific Coast attracted many primarily European immigrants.

The push to settle the Great Plains, the Mountain West, and the Pacific Coast attracted many primarily European immigrants. By the early twentieth century, North America’s economic core was well developed. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to St. Louis, Chicago, and Milwaukee, and from Ottawa to Washington, DC, it dominated North America economically and politically well into the mid-twentieth century.

By the early twentieth century, North America’s economic core was well developed. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to St. Louis, Chicago, and Milwaukee, and from Ottawa to Washington, DC, it dominated North America economically and politically well into the mid-twentieth century. In 1492, roughly 18 million Native Americans lived in North America. By 1542, after only a few European expeditions, there were half that many. By 1907, only about 2 percent of the original population remained; however, by 2010, the Native American population had partially rebounded, to approximately 6 million.

In 1492, roughly 18 million Native Americans lived in North America. By 1542, after only a few European expeditions, there were half that many. By 1907, only about 2 percent of the original population remained; however, by 2010, the Native American population had partially rebounded, to approximately 6 million.