Political Issues

Many political issues in this region are linked to national identity and the image North Americans would like their countries to have. Although North Americans do not participate particularly well in voting (an estimated 57.5 percent of voting age U.S. citizens turned out for the presidential election of 2012, and 61.1 percent of voting age Canadians voted in 2011), citizens of both countries are quite active in less formal democratic institutions, such as community service groups. Here we will look at just a few defining political issues of the present day and especially at the ways in which the two countries are similar and different in terms of political culture.

Post-9/11 Geopolitical Relationships

Immediately after the attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001 (9/11), the international community extended warm sympathy to the country and generally supported the strategies of then President George W. Bush. In the fall of 2001, his administration, with the advice and consent of Congress, launched what was called the War on Terror, defined as a defense of the American way of life and of democratic principles. The first target was Afghanistan, which was then thought to be host to Osama bin Laden and the elusive Al Qaeda network that openly claimed credit for masterminding the 9/11 attacks. The aim was to capture bin Laden—accomplished in 2011, under President Barack Obama, with bin Laden killed by U.S. special forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan—and to remake Afghanistan into a stable ally, an aim still unaccomplished by 2013. Although NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) forces (including Canadian troops) joined U.S. forces in Afghanistan, the war proved difficult to resolve because of heavy resistance from tribal leaders within the country and from militant Muslim insurgents in adjacent Pakistan. Some of the loss of momentum in Afghanistan can be attributed to the fact that in the spring of 2003, President Bush brought the War on Terror to Iraq, and U.S. strategic attention and troop support was diverted.

The war in Iraq persisted from 2003 to 2011, with no real resolution. As of December 2011, U.S. troops had withdrawn from Iraq. By 2012, the United States was following a plan of withdrawing troops and operating instead in an advisory role in Afghanistan. Troops are scheduled to be out in 2014, but the advisory role is to continue in some as yet undefined way. Most analysts agree that despite official withdrawals, a large U.S. military presence is likely to remain in both Iraq and Afghanistan for years to come because of the U.S. long-term strategic interests in the larger Central and Southwest Asian regions (Figure 2.12A, B, and map).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about power and politics in North America, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

RgytHcwNiDCQEXlK0auC0BZ7QVIcLUaUcyskUZU7rmuABZLuHwStpHMQ70JBVlg9sPKlIJvqbsNPfPLUz1nCDD4nObQ5XfusA3YZdY354FIMvnGd8rIeXeOos21zVc+r8H3DswcAWbEVAokwkEsJYwpsw4OWywJBgD+JiTmmIvNrBJwx7V3cxqE5X2280FBkMX1qm0D7Tevln+Fmo5l33fEa0SJziIjoCXefGGFmyP55JjkKlZkdjYODDUU39a8EwjpQA7ErP52424inU4y1MROX7F092T8qSYkhdE+fQObynCzS8GfyIbUBCyPPQExL5VWJtXtfgFZKjHm6JpoF9+z1Ke0+dNbaw1clLUcsKbAKGAQZZpWso2VSml0wmYJ14oI4veOXwF2otRcjNtt5YcUfvW+BtHi40D/F0P2zlgyc2c7D7cdyRyFxbvv6UKDREBjOY6Vw2dz1Kt7IPDAXuXjTnDHIzCzUPjtQMY0KM3gyRI2wGPZt/MP8GOcelDWBEUPL4TiJNl43JVhY3/CZUyldNfkroxnPK1iBMIvZXmh8mUb1t1+q+3a3lljIjNb18vsTYllUndwqISJYGbANelx+fw+w5xJoMzzi0BxgFYD0xE2W0DFixNCZMAHqPMOG2BgAcOd255ZVbByeygS4wI86pBsn0EAmCiFuAlYMo0YMVF2BuvZSwfZIz07c10EAC1VrqDA58qykl/Qj0LwJ0g7E8B82/8U6/sVW4cR52lIcmu77WaARLmeO0s9sdDpPt+FANazwl0oYJpWak2rk5iJx2peyD7AKQuestion

/6t89KcWNA6toH3cVHI/Gfb0R47I9N14gaKuECaSlu6774mS1YKgHUVnr0d4cheFzLfkK7iYkjNrDQK5Ibs1Yk8V4Xeh+kDAGL4asirMZZe1b3WNADdKevN3WWsSt6sNqK9Qkvw2OhRlu8eH5q2zgPOTBhfv1zjdbhgJO28vhtdRt4UKHgTpi3hMf3Icxwtf0mD87h1WPZIQwrNpNMEIM01RmhCYQmEGd3hAGQh9tbnyh9CwAU8ApL7mHdEzioeXgKNBMeizvmWl5Gk+MhGRVMV24ofx9Kfd2OQy04Rw2spCfQhRGDqfZSmRUvYc8xbA3YtiQM5TY6c1a3Iu9moK7LR0jupZJuykZxEPHqwllmsAYnxX2sED6cO2KPgu0kGAVPf4wfooK1QQbCXiSoQP0P55XoYsoEpZbbq7GJS1vdseGQLGI69H8Ij98eTqpLmVjdoa3xDxmqKQ4esZi4yFxUXA7pLQlzvL9fQvbY+8ATox9Gj/Isc7rHCl1eWZrjXbscwdPC/tkoAV57Tr8IdxJa9oDC7XGvFW8pRrHc4TacZd/bWwTXj5Jl+syJ9hzA/h9EwJMjEJD2Zpgdahts/i/GfFf7zx1swThnsSbAFrz3iZgpeqSkEHtXxc6yz18SVGQMS88MzWUAwHX39ni2rdDv0tTXDuuxu6vI0qeMtmvKWAflWXWlKDlw9VpI0ms2cdvXaAwiakghHWLw7yhxd9yfRe+0BdT9VQtT2JYdCcC4YlEV1xc5gUwqNx6n2heLhrx5fiSDQtLjUqnATUl80RLs+UDyCEZN4psOUWRfZNBkFOJ8FVtZPW9Koeoz4/GI+sk3X+RxWzi+j0nxs9kY42YQ3AQV+3FUVx8RevfwebY8ieJ/+p1igVhMgv87oPlummXQBiR8iMHiK8CvolJOxJjAUVj7CUXwlxr9AVrSaX5VUod60QdRbCit/7J/kmRSEVqbgxsXjfH5hnE+QYUi/Qvcj0E9SjBRwEFF818REfKQw1x96Qcv/B/gChA39kKKw2fzuMhKX35urobdY1xjbac3xUUwiiXQkJi5lNEg==Question

Dq9y0tAEC7f1D9Iq1XSFjcQjn3zH94mSHJDDfPcLxrU06QYcr8t/6ARZ8aDvXFCK/lJUQbvTtp0QiOrVBk00QlyfX9Azsl1Zhp+Q9qLy0VnBZPcwRMCW0PUTA2ZYiTyzjYJiCHqkFDabRLn0leC5+FUNSe004mtIBFdqjRJyz8QkA5A+AcI0nvrlj0I7w0H2JjfTKqStEOp54kUR+VNmSlF/XBrJTfDCPiwJEbeRUkt2jvSwxWwx7v6wIUMM3SystF9O9fcvvfD9k0imYnLShIMyFHR2HibBqDEGKj36xSNi6y1sHEwOqeOaHDCJS9fsluFBqH7yfegMssXntaAPRZ3FKZM0JdMgtoKuenuPwOxa8DOZfKZBZn0lzXKAvUWyPbl4Ir3WncFovYJm018ej/NJHwjy8NJ2YVoEh0OCIk4lliyUumDDU06Dp9ybKdS39Ev0HTRoa1hkdl3tnWRXaS14sAihu3fAJ2tj0F/2acDWEdY6vYmSwKOoc3Cu5CmUZcg89VDCe6BZuJ5LHPWg9Qpatmjb1WzygPJCsRTCLH8F5ZoxbuHpTYBdwQqWj1+GJkBbWlr2tYV4WZuWShlLYAduhbFlneyC88i6IKLgrhXTOYikH9NTnYUXaMRCW3diEXV6jX3IG/2UYxDFMqMkKlpz/VE+fIN7cDVbksYqgJwXViz+tCaJIoxEGOFbnkkEENozexIHVxfmPNd9ASFyXQ==Question

Tv72hTz5jOt2wxQSgvxnpEl2bl+shQXlBpN82okjcnlAQ4qR35bnfyBH7zGzGkyDpKSyegQYcxkTdpcoq/A8VzeHbi17xmMszYyV8+M8Dk5lXKaM8bE/EgIbTY1nMuXLcPf2t+QBlzCV9cuUC0JjD1cjUaA0oKjqN/JaeYbSBgTkjCulkXpCO13kANQlMmvs/hkcdoI6tqJDkq4wSVKpqzmSR5G5BJO9mf33clCU1VnHikiZ2++EAWWozmR9ATdhdFWYTHRV4fVtoxRNaNKVTYxUvJ3mL08F9JxdtbeckD9ZwhP5ogrZJe6wbEhRh6O5bZBr4mFPZiTEGaVan2EDqPBVNLapE/kE3Yhm0hK0Lyq3l9WwpRx7dpJ44PWe8V81XleT7p1hDwv8TJQGwFyqygE5xsId4pYYpl6NbD5iWh5ncvAkZz5xCn94opWVVfpnoxVwkgEzsKULbicDtoYOm0P4JLkiut2Ey0Fv2uYnmHM+pM6ZfaBzYhBaHOcmXXalq18XT7yW/hhEzX5l+HPt6+7yfsdutu60fuvA1O0g61zLWxexjAPMnCp2nHSo37AY2dtnFg1+Tof2ImI5The United States and Canada Abroad

Geographic Insight 3

Power and Politics: The interpretation of the ideal of democracy by Canada and the United States has influenced North America’s involvement in the affairs of countries around the world.

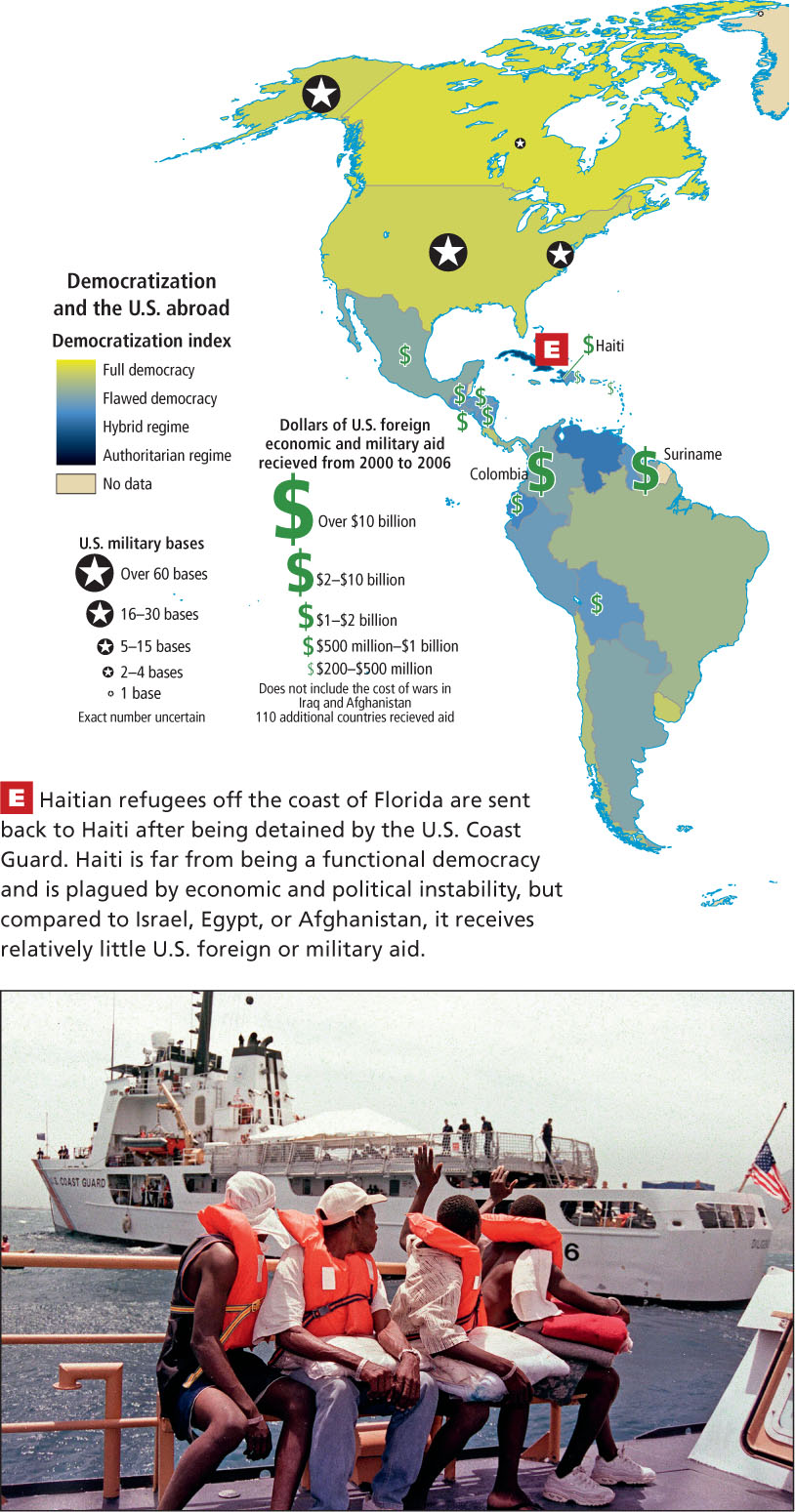

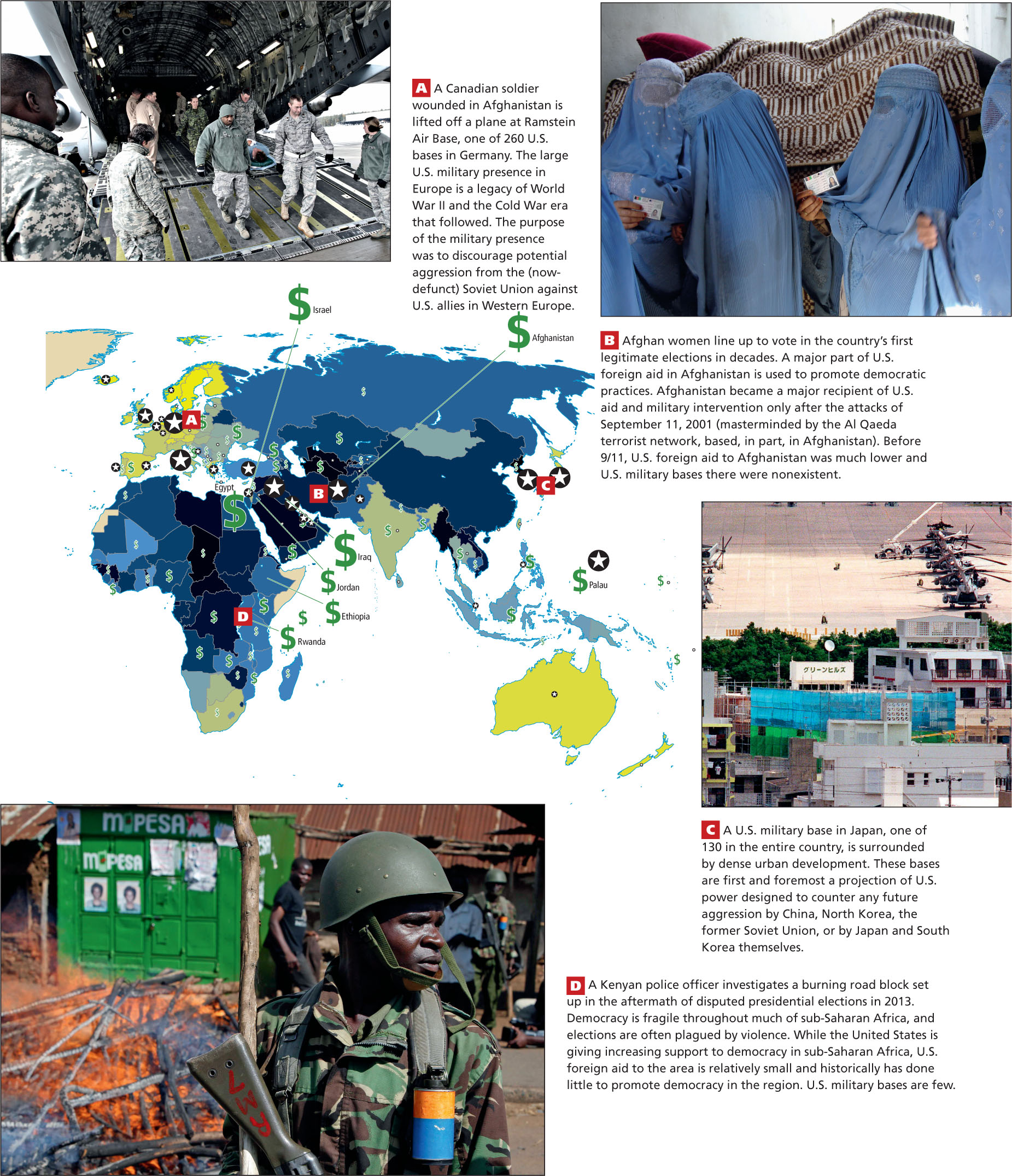

While it is an official policy of both the U.S. and Canadian governments to promote democracy abroad, the two countries approach the project from different perspectives. The United States tends to see itself as the protector of democracy on a global scale, often using an approach that involves the military. Canada, seeking assiduously to distinguish itself from the United States, takes a more “live and let live” approach. Canada’s foreign policies and foreign aid projects tend to be geared toward enhancing civil society by making grants for museums, cultural events, and social services that strengthen local identity and citizen participation. U.S. policies are often correlated to the global distribution of its military bases. U.S. foreign aid sometimes is given to projects meant to enhance human well-being, but it can also be in the form of military assistance. Three main concentrations of military bases and spending, where the United States has for years had strong strategic and economic interests, can be seen on the map in Figure 2.12 in Europe; North Africa and Southwest Asia (Egypt, Israel, Iraq, Jordan), and Afghanistan and Pakistan in South Asia; and island and peninsular Southeast Asia. The first and third concentrations of bases and spending (those in Europe and Southeast Asia) relate to strategic and economic interests dating from World War II that have remained relevant due to the Cold War (see Chapter 1, page 36), the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union (see Chapter 5, pages 263–265), and the opening up of China (see Chapter 9, pages 501–503; see also Figure 2.12C). The second concentration relates directly to U.S. interests in Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Israel, and Egypt and the oil and mineral resources of South and Southwest Asia in general.

76

The map in Figure 2.12 also shows that there are many places where the United States does not have significant bases and where spending on foreign aid is at low or moderate levels. These are generally places where the United States has fewer strategic and economic interests. For example, sub-Saharan Africa’s poverty and ongoing political instability has kept U.S. economic interests few, relative to other, wealthier regions (see Figure 2.12D). (The same could be said of Haiti in the Caribbean; see Figure 2.12E). If U.S. policies to support democracy abroad were a strong factor in the allocation of assistance, one might expect that the focus of U.S. spending on foreign aid and military assistance would be in the parts of sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere that have low levels of democratization. And yet these parts of the world have almost no U.S. bases and only low levels of U.S. spending on foreign aid and military assistance.

39. CONSEQUENCES REPORT

39. CONSEQUENCES REPORT

40. SECURITY AND PERSONAL LIBERTY REPORT

40. SECURITY AND PERSONAL LIBERTY REPORT

41. U.S. IMAGE REPORT

41. U.S. IMAGE REPORT

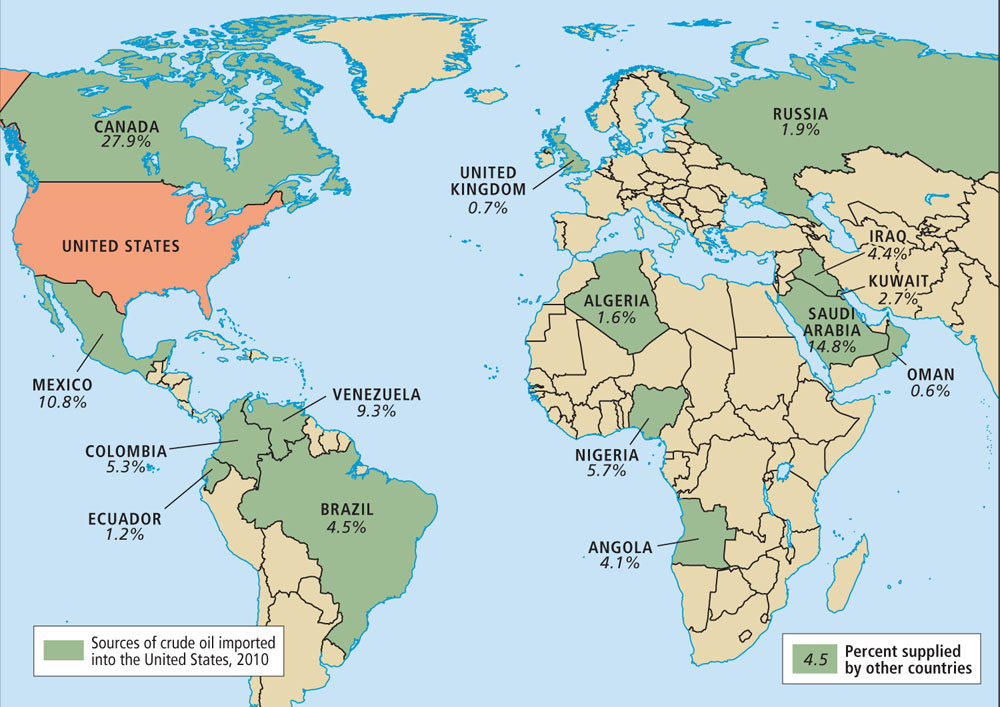

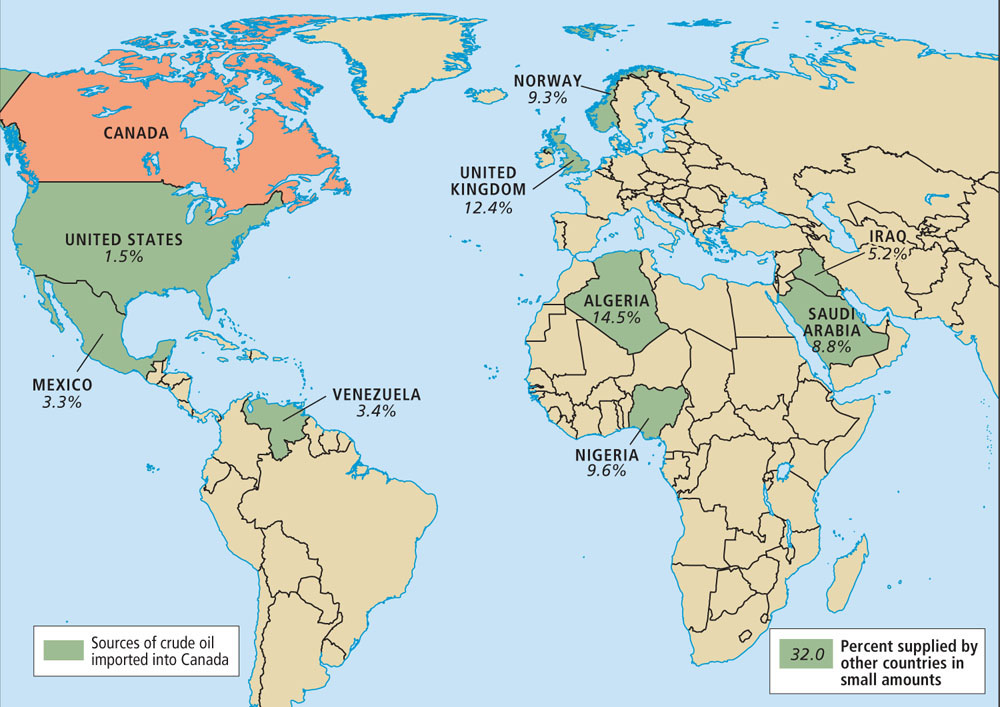

Dependence on Oil Questioned

The 9/11 attacks in 2001 alerted the U.S. public to the fact that the United States was largely dependent on foreign oil. At that time, about 25 percent of imported oil came from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), dominated by countries along the Persian Gulf, where the terrorists had originated. Roughly 46 percent of oil imported into the United States comes from countries that are not part of OPEC (Figure 2.13A). Of this 46 percent, Canada supplies about 21 percent and Mexico about 12 percent (see Figure 2.13A), with 20 other countries supplying only tiny percentages. Meanwhile, Canada, which has the potential to be petroleum independent, actually imports nearly 44 percent of its oil. International oil corporations dominate the oil industry in both countries. Most of Canada’s oil fields are in the west, and at least half of that oil is exported to the United States, where it is refined. Some stays in the United States, and some is sold back to the more heavily populated eastern provinces. The rest of oil imported into eastern Canada comes mostly from OPEC sources (see Chapter 1, page 8). This rate of dependency makes many in both Canada and the United States uncomfortable, especially given the ongoing potentially antagonistic relationships with the Persian Gulf states. Finding more domestic sources of energy has become a major issue for the United States. This has boosted interest in renewable energy, as well as increased pressure in the United States to allow extraction of oil and gas from shale deposits and to drill for oil in coastal waters—though this last strategy was dealt a blow by the massive spill in 2010 involving the Deepwater Horizon, the British Petroleum installation in the Gulf of Mexico.

77

78