Economic Issues

The economic systems of Canada and the United States, like their political systems, have much in common. Both countries evolved from societies based mainly on family farms. Then came an era of industrialization, followed by a move to primarily service-based economies. Both countries have important technology sectors and their economic influence reaches worldwide.

North America’s Changing Food-Production Systems

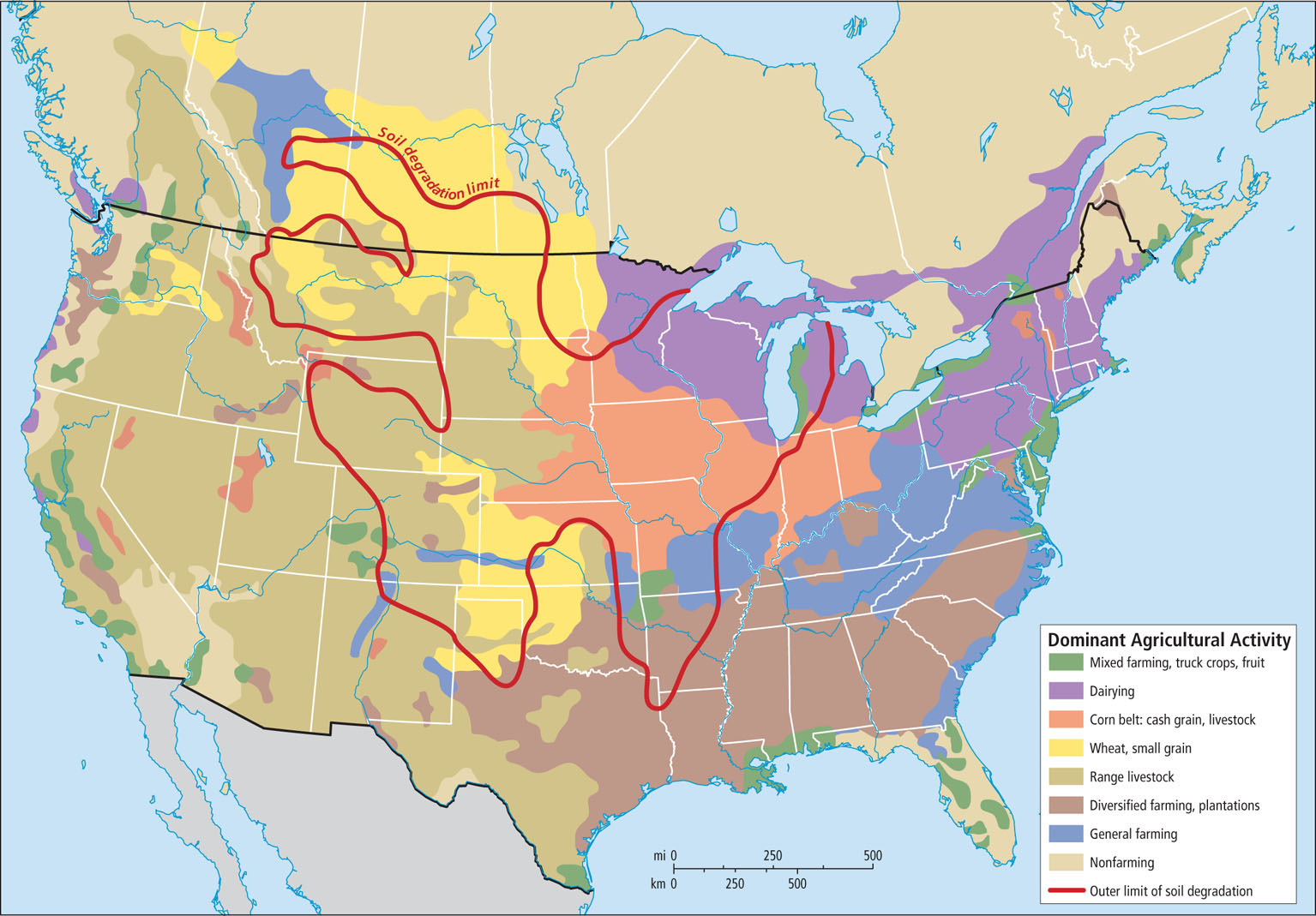

Agriculture remains the spatially dominant feature of North American landscapes, yet less than 1 percent of North Americans are engaged directly in agriculture. North America benefits from an abundant supply of food; it produces food for foreign as well as domestic consumers (Figure 2.17). At one time, exports of agricultural products were the backbone of the North American economy. However, because of growth in other sectors, agriculture now accounts for less than 1.2 percent of the United States’s GDP and less than 2 percent of Canada’s. Moreover, because both countries are involved in the global economy, food in both countries is increasingly being imported.  43. FOOD GLOBALIZATION

43. FOOD GLOBALIZATION

The shift to mechanized agriculture in North America brought about sweeping changes in employment and farm management. In 1790, agriculture employed 90 percent of the American workforce; in 1890, it employed 50 percent. Until 1910, thousands of highly productive family-owned farms, located over much of the United States and southern Canada, provided for most domestic consumption and the majority of all exports. Today, many family farms are being replaced by corporation-owned farms.

Family Farms Give Way to Agribusiness

When family farms began to mechanize in the late nineteenth century with mechanical corn-seed planters and steam-powered threshing machines, such inventions reduced the need for labor to just family members and expanded the amount of land that a family farm could manage. To remain profitable over time, ever larger investments were required in land, sophisticated machinery, fertilizers, pesticides, and farm buildings. By 2000, only younger, wealthier farmers were able to invest in these “green revolution” methods (see Chapter 1, page 26). Some prospered (see the vignette), while some with fewer resources chose to sell their land, hoping to make a profit sufficient for retirement. Indebtedness and bankruptcies are increasingly common experiences for North America’s small farmers. Very recently, some family farmers have been able to earn added income by leasing the mineral rights of their land for natural gas production.

A major part of the transformation of North American agriculture has been the growth of large agribusiness corporations that sell machinery, seeds, and chemicals. These corporations may themselves produce crops on land they bought from retiring farmers, or they may contract with independent farms to produce crops for the corporation. Agribusiness has facilitated the transition to green revolution methods. The corporations’ financial resources have enabled them to invest in research, develop new products, and provide loans and cash to individual farmers. Over time, many farmers have been pressured to enter into contracts and other relationships with agribusiness corporations, leaving these farmers with little actual control over which crops are grown and what farming methods are used.

agribusiness the business of farming conducted by large-scale operations that purchase, produce, finance, package, and distribute agricultural products

83

While green revolution agriculture provides a wide variety of food at low prices for North Americans, the shift to these production methods has depressed local economies and created social problems in many rural areas. Communities in places such as rural Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada, and Iowa, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and Kansas in the United States were once made up of farming families with similar middle-class incomes, social standing, and commitment to the region. Today, farm communities are increasingly composed of a few wealthy farmer-managers amid a majority of poor, often migrant Hispanic or Asian laborers who work on large farms and in food-processing plants for wages that are too low to provide a decent standard of living. They also struggle to be accepted into the communities where they live.

VIGNETTE

The flip side of this story of the decline in North America of the family farm way of life is represented by the burgeoning prosperity of farmers like 37-year-old Twitter user Brandon Hunnicutt, who runs his family’s 3600 acre (1457 hectare) farm above the vast Ogallala Aquifer in Nebraska. He uses the aquifer water to irrigate in dry times and his computer to garner the latest information on nearly every aspect of his operation—from the diagnosis of a crop disease to the right moment for marketing his crops. In the midst of the global recession, he was selling corn at twice the price he received a few years before.

How can this be? In 2007, the rising price of petroleum products spurred the U.S. government to require that ethanol made from corn be added to gasoline in order to lower dependency on foreign energy sources. Now, more than one-third of the corn produced in the United States is converted to ethanol in order to fuel cars and trucks. By 2008, the demand for corn had radically increased, as had its price. As the recession deepened, the value of the U.S. dollar was lowered in order to spur exports. This gave U.S. corn producers an advantage in the world market. Meanwhile, as the economies of Asian countries continued to grow, Asia began buying more and more corn-based food products, especially sweeteners. Bad weather in Russia and Ukraine, which also produce grains, further increased the demand for corn. Corn prices rose globally, to the great advantage of large U.S. producers like Brandon Hunnicutt but to the great anguish of the poor across the world, who had formerly relied on cheap corn as a mainstay in their diets. As shown in the discussion of food security in Chapter 1 (page 24), the vicissitudes of the global economy can bring very different outcomes to different parts of the world. Financial security for farmers like the Hunnicutts can mean food insecurity for the poor in Africa, Asia, and Middle and South America. [Source: NPR staff, All Things Considered. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

84

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Organically Grown

Throughout North America, there is a modest but growing revival of small family farms that supply organically grown (produced without chemical fertilizers and pesticides) vegetables and fruits and grass-fed meat directly to consumers. Farmers’ markets have popped up across the country (Figure 2.18), and customers in ever greater numbers are now buying locally grown organic foods, paying higher prices than those in traditional grocery stores. This movement is gaining such wide favor that large corporate farms are beginning to see the potential for high profits in sustainable (i.e., organic), if not locally grown, food production.

organically grown products produced without chemical fertilizers and pesticides

Courtesy Mac Goodwin

Greater interest in sustainable food production may reduce harmful impacts on the environment as farms shift over to organic methods and consumers learn the advantages of paying more for higher quality, toxin-free vegetables and fruits.

Food Production and Sustainability

Can green revolution agriculture, like that practiced by successful North American corn farmers, persist over time? First, there is concern over the long-term impacts of genetically modified (GMO) crops on human health (see Chapter 1, page 27). Such crops are too new to have been adequately tested. Second, modernized strategies to increase yields—including irrigation, computerized tractors, GMO seeds, as well as chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides—can have negative environmental impacts. These methods can contaminate food, use scarce water resources, pollute nearby streams and lakes, and even affect distant coastal areas. In addition, many North American farming areas have lost as much as one-third of their topsoil due to deep plowing and other farming methods that create soil erosion. But these worries about sustainability are not the whole story. Scientists have shown that, given a little time, they can adjust green revolution technologies to enhance sustainability. For example, there is evidence now that corn genetically modified with a gene from a bacteria that is poisonous to the corn borer—a destructive insect that came from Europe in about 1917 and has repeatedly devastated corn crops—has greatly reduced the corn borer population. The protection has spread to adjacent fields grown with conventional seeds. The GMO seed companies now encourage farmers to grow traditional corn in fields adjacent to GMO corn to reduce the possibility that the corn borer will develop immunity to the genetically modified poison.

Nonetheless, there are growing concerns about the sustainability of rapidly changing patterns of food production. These concerns, expressed in a variety of books and articles over the last two decades, point out that federal subsidies to American agriculture have encouraged the drift to factory farms where animals are bred, tended to in crowded conditions, and fed chemicals to enhance weight gain. Vast quantities of animal waste produce environmental hazards. Furthermore, the current subsidized system has encouraged the monoculture of corn, soybeans, wheat, and rice, leading to the production of high-sugar, high-carbohydrate foods that contribute to obesity and diabetes. The critiques coalesce around the idea of changing the subsidy structure to favor small farmers, encouraging them to go back to more traditional methods, at least in food agriculture.

Changing Transportation Networks and the North American Economy

An extensive network of road and air transportation, enabling high-speed delivery of people and goods, is central to the productivity of North America’s economy. The development of this system began as early as 1800 (see Figure 2.11) and edged toward a nationwide network with the development of inexpensive mass-produced automobiles in the 1920s. Where railroads and water-borne shipping had once dominated transportation, trucks could now deliver cargo more quickly and conveniently. Beginning in the 1950s, automobile- and truck-based transport was boosted by the Interstate Highway System—a 45,000-mile (72,000-kilometer) network of high-speed, multilane roads. Because this network is connected to the vast system of local roads, it can be used to deliver manufactured products faster and with more flexibility than can be done using the rail system. Thus the highways have made possible the dispersal of industry and related services into suburban and rural locales across the country, where labor, land, and living costs are lower.

85

After World War II, air transportation also enabled economic growth in North America. The primary niche of air transportation is business travel, because face-to-face contact remains essential to American business culture despite the growth of telecommunications and the Internet. Because many industries are widely dispersed in numerous medium-size cities, air service is organized as a hub-and-spoke network. Hubs are strategically located airports, such as those in Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, and Los Angeles. These airports are used as collection and transfer points for passengers and cargo continuing on to smaller locales. Most airports are also located near major highways, which provide an essential link for high-speed travel and cargo shipping.

The New Service and Technology Economy

Geographic Insight 4

Globalization and Development: Globalization has transformed economic development in North America, thereby changing trade relationships and the kinds of jobs available in this region.

As the trend toward global economic interdependency has taken hold, the North American job market has become more oriented toward knowledge-intensive jobs that require education and specialized professional training, often in high-tech fields or management. Meanwhile, the relatively low-skill, mass-production industrial jobs upon which the region’s middle class was built have increasingly moved abroad.

46. U.S. GEOGRAPHY REPORT

46. U.S. GEOGRAPHY REPORT

The Decline in Manufacturing Employment

By the 1960s, the geography of manufacturing was changing. In the old economic core, higher pay and benefits and better working conditions won by labor unions led to increased production costs. Many companies began moving their factories to the southeastern United States, where wages were lower due to the absence of labor unions.  44. U.S. LABOR TRANSITION REPORT

44. U.S. LABOR TRANSITION REPORT

In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was passed. In response, many manufacturing industries, such as clothing, electronic assembly, and auto parts manufacturing, began moving farther south to Mexico or overseas. In these locales, labor was vastly cheaper. Furthermore, employers saved on production costs because laws mandating environmental protection as well as safe and healthy workplaces were absent or less strictly enforced.

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) a free trade agreement made in 1994 that added Mexico to the 1989 economic arrangement between the United States and Canada

Another factor in the decline of manufacturing employment is automation. The steel industry provides an illustration. In 1980, huge steel plants, most of them in the economic core, employed more than 500,000 workers. At that time, it took about 10 person-hours and cost about $1000 to produce 1 ton of steel. Spurred by more efficient foreign competitors in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, the North American steel industry applied new technology to lower production costs, improve efficiency, and increase production. By 2006, steel was being produced at the rate of 0.44 person-hours per ton and at a cost of about $165 per ton. As a result, the steel industry in the United States reorganized with much steel produced in small, highly efficient mini-mills. In total, the steel industry now employs fewer than half the workers it did in 1980. Throughout North America, this efficiency trend has resulted in far fewer people producing more of a given product at a far lower cost than was the case 30 years ago. Remarkably, even as employment in manufacturing has declined over the last three decades, the actual amount of industrial production has steadily increased.

Growth of the Service Sector

The economic base of North America is now a broad tertiary sector in which people are engaged in various services such as transportation, utilities, wholesale and retail trade, health, leisure, maintenance, finance, government, information, and education.

As of 2012, in both Canada and the United States, about 75 percent of jobs and a similar percentage of the GNI were in the tertiary, or service, sector. There are high-paying jobs in all the service categories, but low-paying jobs are far more common. The largest private employer in the United States is the discount retail chain Walmart (1.4 million employees in 2011), where the average wage is $12 an hour, or $24,000 a year, full time. This is just barely above the poverty level for a family of four in the United States. Because many Walmart employees are part time, a large percentage do not receive benefits, such as health care. Walmart creates primarily retail jobs because, for the most part, its wares are manufactured abroad.

Service jobs are often connected in some way to international trade. They involve the processing, transport, and trading of agricultural and manufactured products and related information that are either imported to or exported from North America. Hence, international events can shrink or expand the numbers of these jobs rather precipitously.

The Knowledge Economy

An important subcategory of the service sector involves the creation, processing, and communication of information—what is often labeled the knowledge economy, or the quaternary sector. The knowledge economy includes workers who manage information, such as those employed in finance, journalism, higher education, research and development, and many aspects of health care.

Industries that rely on the use of computers and the Internet to process and transport information are freer to locate where they wish than were the manufacturing industries of the old economic core, which depended on locally available steel and energy, especially coal. These newer industries are more dependent on highly skilled managers, communicators, thinkers, and technicians, and are often located near major universities and research institutions. They may also be located in clusters of companies involved with the subset of the knowledge economy, known as the information technology (or IT) sector, which deals with computer software, hardware, and the management of digital data.

86

Crucial to the knowledge economy is the Internet, which was first widely available in North America and has emerged as an economic force more rapidly there than in any other region in the world. China surpassed North America in actual numbers of Internet users in about 2005. It now has 23 percent of the world’s users; however, only about 36 percent of China’s population has Internet access, the Internet is tightly controlled in China, and purchasing via the Internet has not yet taken off there. North America, with only 5 percent of the world’s population, accounted in 2011 for 11.6 percent of the world’s Internet users. Roughly 78 percent of the population of the United States uses the Internet, as does 85 percent of the Canadian population, compared to 67 percent in the European Union and 30.2 percent for the world as a whole. The total economic impact of the Internet in North America is hard to assess, but retail Internet sales increase every year. Indeed, during the recession of 2008 to 2011, while overall purchases were down, online purchases in the United States and Canada steadily increased.

Internet-based social networking (Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, YouTube, and others) has now moved well beyond mere personal communication to play a rapidly expanding role in marketing for large retail firms and especially for small businesses, which use these facilities to keep almost constant contact with their customers.

The Internet has also entered the political sphere, with social networking having played a large role in recruiting volunteers and eliciting cash contributions, especially during recent U.S. election cycles and in all subsequent elections. Beginning in 2009, social networking through Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube became an integral part of public communication, often referred to on daily TV news programming; it played a particularly active role in the Occupy Wall Street protests and is now a major source of information for North Americans about international events, such as the Arab Spring demonstrations around the Mediterranean.

The growth of Internet-based activity in North America makes access to the Internet increasingly crucial. Unfortunately, a digital divide has developed, because nearly a fifth of the North American population is not yet able to afford computers and Internet connections.

digital divide the discrepancy in access to information technology between small, rural, and poor areas and large, wealthy cities that contain major governmental research laboratories and universities

Globalization and the Economy

Today, North America remains the wealthiest and most technologically advanced presence in the global economy. The United States and Canada impact the world economy because of the size of their economies—together, they are almost as large as the economy of the entire European Union—and their affluent consumers. North America’s advantageous position in the global economy is also a reflection of its geopolitical influence—its ability to mold the pro-globalization free trade policies that suit the major corporations and the governments of Canada and the United States.

Free trade has not always been emphasized the way it is now. Before North America’s rise to prosperity and global dominance, trade barriers were important aids to its development. For example, when it became independent of Britain in 1776, the new U.S. government imposed tariffs and quotas on imports and gave subsidies to domestic producers. This protected fledgling domestic industries and commercial agriculture, allowing its economic core region to flourish.

Now, because both are wealthy and globally competitive exporters, Canada and the United States see tariffs and quotas in other countries as obstacles to North America’s economic expansion abroad. Thus, they usually advocate heavily for the reduction of trade barriers worldwide. Critics of these free trade policies point out a number of fallacies in the present North American position on free trade. First, North America once needed tariffs and quotas to protect its fledgling firms, much like many currently poorer countries still need to do. Furthermore, both the United States and Canada, contrary to their own free trade precepts, still give significant subsidies to their farmers. These subsidies make it possible for North American farmers to sell their crops on the world market at such low prices that farmers elsewhere are hurt or even driven out of business (see the vignette). For example, many Mexican farmers have lost their small farms because of competition from large U.S. corporate farms, which receive subsidies from the U.S. government. U.S. corporate farms can now sell their produce in Mexico or even relocate there under NAFTA agreements. The critics add that beyond agriculture, the benefits of free trade in North America go mostly to large manufacturers and businesses and their managers, while many workers end up losing their jobs to cheaper labor overseas, or see their incomes stagnate.

NAFTA

Trade between the United States and Canada has been relatively unrestricted for many years. The process of trade barrier reduction formally began with the Canada–U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1989. With the creation of NAFTA in 1994, Mexico has now been included. The major long-term goal of NAFTA is to increase the amount of trade between Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Today, it is the world’s largest trading bloc in terms of the GDP of its member states.

The extent of the impacts of NAFTA are hard to assess because it is difficult to tell whether the many observable changes are due to the actual agreement or to other changes in regional and global economies. However, a few things are clear. NAFTA has increased trade, and many companies are making higher profits because they now have larger markets. Since 1990, exports among the three countries have increased in value by more than 300 percent. NAFTA’s exports to the world economy, by value, have increased by about 300 percent for the United States and Canada and by 600 percent for Mexico. Some U.S. companies, such as Walmart, expanded aggressively into Mexico after NAFTA was passed. Mexico now has more Walmarts (2088 retail stores) than any country except the United States (Figure 2.19). Canada has 333 Walmarts; the United States has 3868.

87

NAFTA seems to have worsened the long-standing tendency for the United States to spend more money on imports than it earns from exports. This imbalance is called a trade deficit. Before NAFTA, the United States had much smaller trade deficits with Mexico and Canada. After the agreement was signed, these deficits rose dramatically, especially with Mexico. For example, between 1994 and 2009, the value of U.S. exports to Mexico increased by about 153 percent, while the value of imports increased 265 percent.

trade deficit the extent to which the money earned by exports is exceeded by the money spent on imports

NAFTA has also resulted in a net loss of around 1 million jobs in the United States. Increased imports from Mexico and Canada have displaced about 2 million U.S. jobs, while increased exports to these countries have created only about 1 million jobs. Some new NAFTA-related jobs do pay up to 18 percent more than the average North American wage. However, those jobs are usually in different locations than the ones that were lost, and the people who take them tend to be younger and more highly skilled than those who lost jobs. Former factory workers often end up with short-term contract jobs or low-skill jobs that pay the minimum wage and carry no benefits.

As the drawbacks and benefits of NAFTA are being assessed, talk of extending it to the entire Western Hemisphere has stalled. Such an agreement, which would be called the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), would have its own drawbacks and benefits. A number of countries, such as Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, are wary of being overwhelmed by the U.S. economy. Even in the absence of such an agreement, trade between North America and Middle and South America is growing faster than trade with Asia and Europe. This emerging trade is discussed in Chapter 3.

The Asian Link to Globalization

Another way in which the North American economy is becoming globalized is through the lowering of trade barriers with Asia. One huge category of trade with Asia is the seemingly endless variety of goods imported from China—everything from underwear to the chemicals used to make prescription drugs. China’s lower wages make its goods cheaper than similar products imported from Mexico, despite Mexico’s proximity and membership in NAFTA. Indeed, many factories that first relocated to Mexico from the southern United States have now moved to China to take advantage of its enormous supply of cheap labor. Despite adjustments in the Chinese economy that may raise prices, trade with China promises to remain quite robust for some time.

U.S. and Canadian companies also want to take advantage of China’s vast domestic markets. For example, the U.S. fast-food chain Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) now has more than 2100 locations in 450 cities in China, and its business is growing rapidly there. The U.S. government has a powerful incentive to encourage such overseas expansion by companies like KFC that are headquartered in the United States and whose repatriated profits are taxable by the federal government.

88

Asian investment in North America is also growing. For example, Japanese and Korean automotive companies located plants in North America to be near their most important pool of car buyers—commuting North Americans. They often located their plants in the rural mid-South of the United States or in southern Canada, close to arteries of the Interstate Highway System. Here the Asian companies found a ready, inexpensive labor force. These workers could access high-quality housing in rural settings within a commute of 20 miles (32 kilometers) or so from secure automotive jobs that paid reasonably well and included health and retirement benefit packages.

Japanese and Korean carmakers succeeded in North America even as U.S. auto manufacturers such as General Motors were struggling. This was primarily because more-advanced Japanese automated production systems—requiring fewer but better-educated workers—produce higher-quality cars, which sell better both in North America and globally. Some analysts predict that foreign carmakers will eventually take over the entire North American market, while others predict that the old American car companies, several of which are in the process of restructuring, will turn out more competitive, smaller, better-built, and more fuel-efficient cars. Note that General Motors saw its highest profit in its history in 2011 ($7.6 billion), paid back its bailout loan, and is producing autos that are increasingly popular with North American consumers (see the New York Times article, “G.M. Reports Big Profit; Europe Lags,” at http://tinyurl.com/8yf8fk7, for more on this).

IT Jobs Face New Competition from Developing Countries

By the early 2000s, globalization was resulting in the offshore outsourcing of information technology (IT) jobs. A range of jobs—from software programming to telephone-based, customer-support services—shifted to lower-cost areas outside North America. By the middle of 2003, an estimated 500,000 IT jobs had been outsourced, and forecasts are that 3.3 million more will follow by 2020. During the recent recession, IT jobs were still being created at a faster rate than they were being ended by economic contraction, yet the overall trend pointed to fewer and fewer of the world’s total IT jobs staying in North America. New IT centers are now located in India, China, Southeast Asia, the Baltic states in North Europe, Central Europe, and Russia. In these areas, large pools of highly trained, English-speaking young people work for wages that are 20 to 40 percent of their American counterparts’ pay. Some argue that rather than depleting jobs, outsourcing will actually help job creation in North America by saving corporations money, which will then be reinvested in new ventures. The viability of this pro-outsourcing argument remains unproven.  45. U.S. COMPETITIVENESS

45. U.S. COMPETITIVENESS

Repercussions of the Global Economic Downturn Beginning in 2007

The severe worldwide economic downturn that began in 2007 came on the heels of a long global upward trajectory of economic expansion. A booming housing industry and related growth in the underregulated banks that finance home mortgages fueled this growth in the United States. In 2007, the housing industry collapsed as it became clear that much of the growth in previous years had been based on banks allowing millions of buyers to purchase homes with mortgages that were well beyond their means. Thus the boom in the construction industry, based on erroneous assumptions, came to a sudden halt. When too many homebuyers could no longer afford their mortgage payments, the banks that had lent them money, and/or the institutions to which the banks had sold these mortgages, started to fail. The bank failures produced worldwide ripple effects because so many foreign banks were involved in the U.S. housing market. Between September 2008 and March 2009, the U.S. stock market fell by nearly half, wiping out the savings and pensions for millions of Americans. Similar plunges followed in foreign stock markets, ultimately resulting in a worldwide economic downturn as businesses could no longer find money to fund expansion.

As the recession intensified, job losses in the United States caused a sharp drop in consumption, which further affected world markets, including those in Canada. Canada did not have bank failures because of strong regulatory controls. However, because so much of the Canadian economy is linked to exports and imports from the United States (see Figure 2.15), Canada underwent a massive slowdown. During three quarters in 2009, its GNI declined by 3.3 percent, and exports fell by 16 percent. Canada also suffered a high rate of job losses; but the recovery was quicker than in the United States, possibly because household consumption was buttressed by Canada’s strong social safety net, plus some Canadian incomes were stabilized by global demand for Canadian energy resources. However, Canadian household indebtedness increased sharply into 2011. A Bank of Canada official concluded in 2011 that while Canada weathered the recession fairly well, the recession brought changes that may be lasting.

Growing concern with the U.S. national debt (Canada’s national debt is roughly comparable in size), which consists of the money borrowed by issuing treasury securities to cover expenses that exceed income from taxes and other revenues, exacerbated the perception of financial disaster in the United States. There are two components to the U.S. debt: debt held by the public, including that held by investors, the Federal Reserve System, and foreign, state, and local governments ($10.5 trillion as of January 2012); and debt held in accounts administered by the federal government, such as that borrowed from the Social Security Trust Fund ($4.7 trillion as of January 2012).

To whom does the United States owe its debt? About 70 percent of the total debt is owed to Americans who own Treasury securities or to various federal government entities, like the Social Security Trust Fund. About 29 percent is owed to foreign governments (8 percent to China, 5 percent to Japan, 2 percent to the United Kingdom, and smaller amounts to Brazil, Taiwan, and Hong Kong).

The debt constituted a major issue during the U.S. 2012 election cycle. Republicans held that the debt was dangerous and needed to be reduced immediately by drastically reducing government services. Democrats held that some services should be cut and that revenues should be raised by taxing the very rich (who, at the time, were paying taxes at significantly lower rates than middle-income people); also, creating jobs through government programs would alleviate the recession.

89

Women in the Economy

Geographic Insight 5

Population and Gender: Side effects of changes in gender roles and in opportunities for women include some improvements in education and pay equity; smaller families; and the aging of North America’s population.

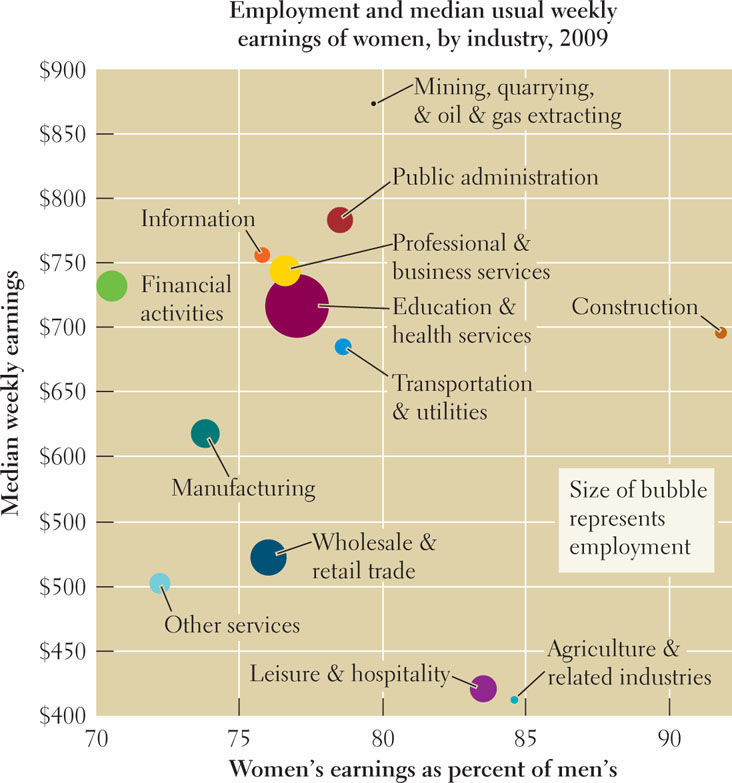

While women have made steady gains in achieving equal pay and overall participation in the labor force, there are still important ways in which they lag behind their male counterparts. On average, U.S. and Canadian female workers earn about 80 cents for every dollar that male workers earn for doing the same job (Figure 2.20). For example, a female architect earns approximately 80 percent of what a male architect earns for performing comparable work. This situation is actually an improvement over previous decades. During World War II, when large numbers of women first started working in male-dominated jobs, North American female workers earned, on average, only 57 percent of what male workers earned. The advances made by this older generation of women and the ones that followed have transformed North American workplaces. For the first time in history, women now represent more than half of the North American labor force, though most still work for male managers.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Women in Business and Education

Throughout North America, women entrepreneurs are increasingly active, starting nearly half of all new businesses. While women-owned businesses do tend to be small and less financially secure than those in which men have dominant control, credit opportunities for businesswomen are improving as women go into upper-level jobs in banking. Change is also coming to the private sector, where a 2012 study showed that male executives now prefer to hire qualified women because they are particularly ambitious and willing to gain advanced qualifications.

In secondary and higher education, North American women have equaled or exceeded the level of men in most categories. In 2008 in the United States, 33 percent of women age 25 and over held an undergraduate degree, compared to just 26 percent of men. This imbalance is likely to increase because in 2010, U.S. women age 25 to 29 were receiving 7 percent more undergraduate degrees than were men.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

North American farms have become highly mechanized operations that need few workers. To be profitable, however, they require huge investments in land and machinery, as well as the use of fertilizers and pesticides that contribute to water pollution.

North American farms have become highly mechanized operations that need few workers. To be profitable, however, they require huge investments in land and machinery, as well as the use of fertilizers and pesticides that contribute to water pollution. In the twentieth century, the mass production of inexpensive automobiles and trucks, as well as development of the Interstate Highway System, fundamentally changed how people and goods move across the continent.

In the twentieth century, the mass production of inexpensive automobiles and trucks, as well as development of the Interstate Highway System, fundamentally changed how people and goods move across the continent. _div_Geographic Insight 4_enddiv_Globalization and Development Global economic interdependency has meant that certain kinds of jobs in North America are vulnerable to outsourcing. Employment is increasingly in knowledge-intensive jobs that require higher education for professions or specialized technical training. Meanwhile, low-skill, mass-production industrial jobs are increasingly being moved abroad. Also, NAFTA has affected both job loss and job creation.

_div_Geographic Insight 4_enddiv_Globalization and Development Global economic interdependency has meant that certain kinds of jobs in North America are vulnerable to outsourcing. Employment is increasingly in knowledge-intensive jobs that require higher education for professions or specialized technical training. Meanwhile, low-skill, mass-production industrial jobs are increasingly being moved abroad. Also, NAFTA has affected both job loss and job creation. Flows of trade and investment between North America and Asia have increased dramatically in recent decades.

Flows of trade and investment between North America and Asia have increased dramatically in recent decades. _div_Geographic Insight 5_enddiv_Population and Gender The participation by women in the economy is beginning to rival that of men, yet women’s average pay remains low. Younger women are focusing on educational achievement.

_div_Geographic Insight 5_enddiv_Population and Gender The participation by women in the economy is beginning to rival that of men, yet women’s average pay remains low. Younger women are focusing on educational achievement.