3.1 3 Middle and South America

3.1.1 Geographic Insights: Middle And South America

Geographic Insights: Middle And South America

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the nine thematic concepts:

1. Climate Change and Deforestation: Deforestation in this region contributes to climate change by removing trees, which as living plants naturally absorb carbon dioxide. As the cut vegetation decays, large amounts of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere. Sustainable alternatives to deforestation are being tried.

2. Water: Despite the region’s abundant water resources, parts of the region are experiencing a water crisis related to unplanned urbanization; marketization; corruption; inadequate water infrastructure; and the use of water to irrigate commercial agriculture.

3. Globalization, Development, Power, and Politics: The integration of this region with the world economy has led to growing disparities of wealth and opportunity, forcing millions to migrate in search of work. A political backlash against these patterns of development has brought to power some leaders who question the benefits of globalization as well as others who seek to help their countries compete globally.

4. Food and Urbanization: The shift from small-scale subsistence food production to mechanized agriculture for export has fueled migration to cities. Many places previously were self-sufficient with regard to food; they now depend on imported food, making them susceptible to food insecurity.

5. Population: A population explosion in the twentieth century has given this region about 596 million people, more than 10 times the population of the region in 1492. Now social and economic changes, including urbanization and the availability of contraception, are giving women options other than raising a family.

6. Gender: Traditional gender roles are changing as women work outside the home and manage families while many men are migrating to other places for work. Also, urbanization is reducing the influence of extended families, opening the door for many types of social change.

The Middle and South American Region

Middle and South America, like North America, is a region of great physical and cultural diversity (see Figure 3.1); but here the cultural mix is, if anything, richer and there are wider disparities of wealth than in any other world region. In spite of many similarities, modern history in Middle and South America has been very different from that of North America. The nine thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights above. Vignettes—like the one that follows about the Secoya—illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

VIGNETTE

The boat trip down the Aguarico River in Ecuador took me into a world of magnificent trees, river canoes, and houses built high up on stilts to avoid floods. I was there to visit the Secoya, a group of 350 indigenous people locked in negotiations with the U.S. oil company Occidental Petroleum over its plans to drill for oil on Secoya lands. Oil revenues supply 40 percent of the Ecuadorian government’s budget and are essential to paying off its national debt. The government had threatened to use military force to compel the Secoya to allow drilling.

The Secoya wanted to protect themselves from pollution and cultural disruption. As Colon Piaguaje, chief of the Secoya, put it to me, “A slow death will occur. Water will be poorer. Trees will be cut. We will lose our culture and our language, alcoholism will increase, as will marriages to outsiders, and eventually we will disperse to other areas.” Given all the impending changes, Chief Piaguaje asked Occidental to use the highest environmental standards in the industry. He also asked the company to establish a fund to pay for the educational and health needs of the Secoya people.

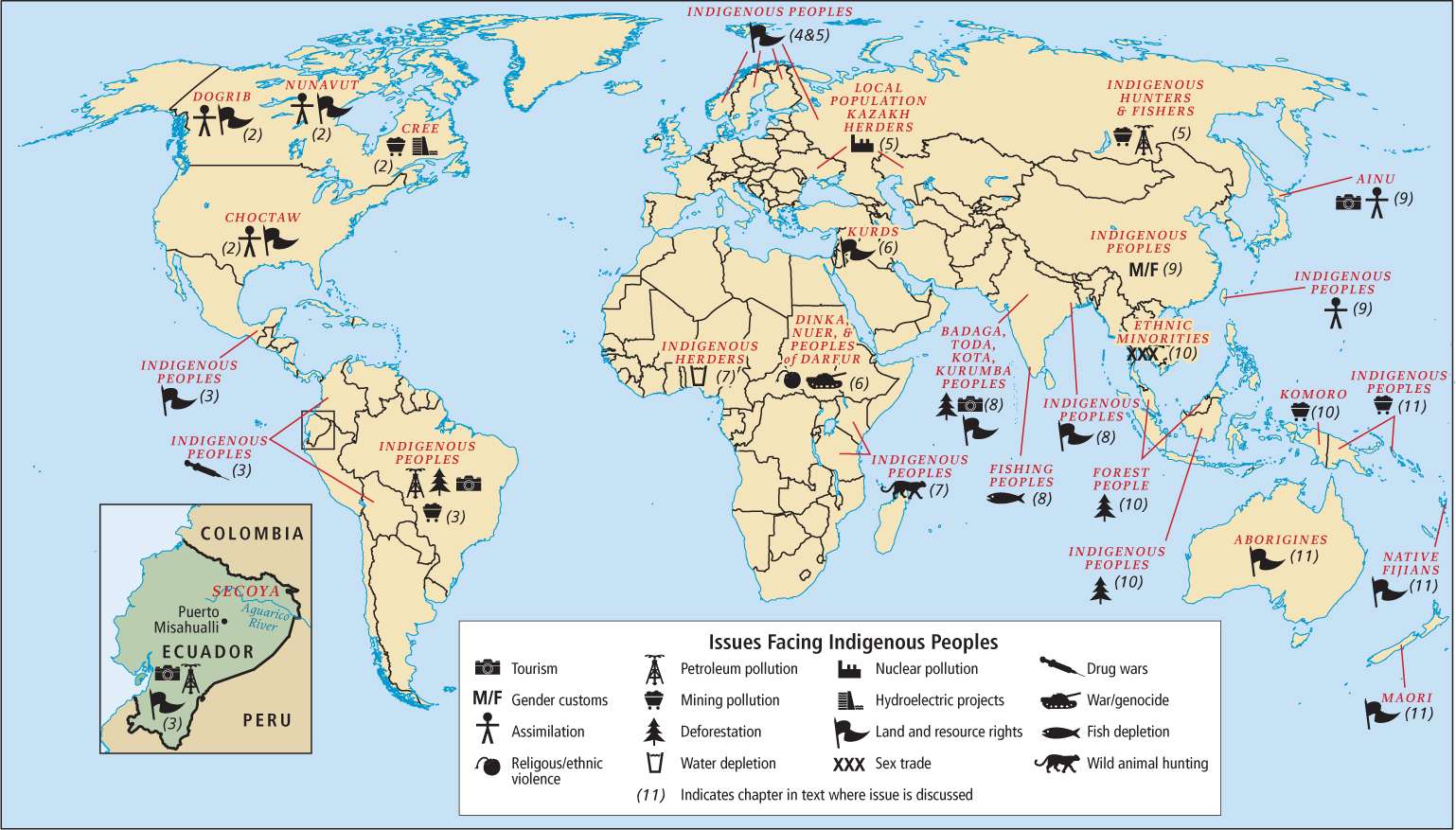

Like the Secoya, indigenous peoples around the world are facing environmental and cultural disruption arising from economic development efforts. Chief Piaguaje based his predictions for the future on what has happened in other parts of the Ecuadorian Amazon that have already had several decades of oil development.

The U.S. company Texaco was the first major oil developer to establish operations in Ecuador. From 1964 to 1992, its pipelines and waste ponds leaked almost 17 million gallons of oil into the Amazon Basin, enough to fill about 1900 fully loaded oil tanker trucks, or 35 Olympic-size swimming pools. Although Texaco sold its operations to the government and left Ecuador in 1992, its oil wastes continue to leak into the environment from hundreds of open pits (Figure 3.2).

In 1993, some 30,000 people sued Texaco for damages in New York State, where the company (now owned by and called Chevron) is headquartered, for damages from the pollution. Those suing were both indigenous people and settlers who had established farms along Texaco/Chevron’s service roads. Several epidemiological studies concluded that oil contamination has contributed to higher rates of childhood leukemia, cancer, and spontaneous abortions among people who live near the pollution created by Texaco/Chevron. Also, oil development has had many negative effects on the environment. Air and water pollution have increased rates of illness. The wildlife that the Secoya used to depend on, such as tapirs, have disappeared almost entirely because of overhunting by new settlers from the highlands who are working in the oil industry.

In 2002, the Ecuadorian suit against Chevron was dismissed by the U.S. Court of Appeals, but it was refiled in Ecuador in 2003. In 2011 the Ecuadorian court ruled against Chevron, assessing damages of U.S.$18 billion. Chevron appealed to the Ecuadorian Supreme Court. This decision could go against Chevron; however, because Chevron no longer has any assets in Ecuador, the villagers may never collect. [Sources: Alex Pulsipher’s field notes; Amazon Watch, 2006; Oxfam America, 2005; National Public Radio. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

The rich resources of Middle and South America have attracted outsiders since the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Europe’s encounter with this region marked a major expansion of the global economy. However, during most of the period of expansion, Middle and South America occupied a disadvantaged position in global trade, supplying cheap raw materials that aided the Industrial Revolution in Europe and then North America but reaping few of the profits. These extractive industries did little to advance economic development within the region, as most profits went to foreign investors, and the negative environmental effects were largely ignored. In recent years, countries such as Ecuador, Mexico, Bolivia, Brazil, and Venezuela have worked to control their own resources, develop local industries, keep profits at home, and limit environmental pollution. Meanwhile, trade blocs within the region are creating conditions in which these countries can prosper from trade with each other.

Secoya villagers’ efforts to secure a damage settlement against a powerful multinational corporation is indicative of changing attitudes in this region and others (Figure 3.3) toward outside developers. Governments are now somewhat more transparent and savvy when they lure investors to develop new extractive, manufacturing, and service industries. Local people are more aware that they must be vigilant to ensure that development serves their interests.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The region of Middle and South America, heavily impacted by European colonialism, is making a shift away from raw materials–based industries to more profitable manufacturing and service-based industries.

The region of Middle and South America, heavily impacted by European colonialism, is making a shift away from raw materials–based industries to more profitable manufacturing and service-based industries. As people in this region gain more control over their own resources, some are searching for more sustainable ways to develop.

As people in this region gain more control over their own resources, some are searching for more sustainable ways to develop.