Sociocultural Issues

Under colonialism, a series of social structures evolved that guided daily life—standard ways of organizing the family, community, and economy. They included rules for gender roles, race relations, and religious observance. These social structures, combined with economic systems, influenced population distribution and growth. Traditional social structures, still widely accepted in the region, are nonetheless changing in response to economic development, urbanization, migration, and globalization. The results are varied. In the best cases, change is leading to a new sense of initiative on the part of women, men, and the poor. In the worst cases, the result is a loss of economic viability and community cohesion and the breakdown of family life, with some of the most extreme impacts felt by indigenous communities.

Population Patterns

Geographic Insight 5

Population: A population explosion in the twentieth century has given this region about 596 million people, more than 10 times the population of the region in 1492. Now social and economic changes, including urbanization and the availability of contraception, are giving women options other than raising a family.

Today, populations in Middle and South America continue to grow but at an ever-slower pace than in the past because of lower birth rates. At the same time, a major migration from rural to urban areas is redistributing people and transforming traditional ways of life. A second trend, international migration, is also growing as many people leave their home countries, temporarily or permanently, to seek opportunities in the United States and Europe, and also in neighboring countries. As of 2011, about 596 million people were living in Middle and South America, close to 10 times the highest estimated population of the region in 1492.

Population Distribution

The population density map of this region reveals a very unequal distribution of people. Comparing the population map (Figure 3.20) with the landforms map (see Figure 3.1), you will find areas of high population density in a variety of environments. Some of the places with the highest densities, such as those around Mexico City and in Colombia and Ecuador, are in highland areas. But high concentrations are also found in lowland zones along the Pacific coast of Central America and especially along the Atlantic coast of South America. The cool uplands (tierra templada) were densely occupied even before the European conquest. Most coastal lowland concentrations, in the tierra caliente, are near seaports with vibrant globalizing economies and a cosmopolitan social life that attracts people.

Population Growth

During the twentieth century, cultural and economic factors combined with improvements in health care to create a population explosion. High birth rates were sustained in part because the Roman Catholic Church discourages systematic family planning, and cultural mores encouraged men and women to reproduce prolifically. In agricultural areas, children were seen as sources of wealth because they could do useful farm and household work at a young age and eventually would care for their aging elders. Worry over infant death rates persisted, so some parents had four or more children to be sure of raising at least a few to adulthood. But, by 1975, child death rates were one-third what they had been in 1900. Most of the recent population growth has been related to longer life expectancy, not to high birth rates.

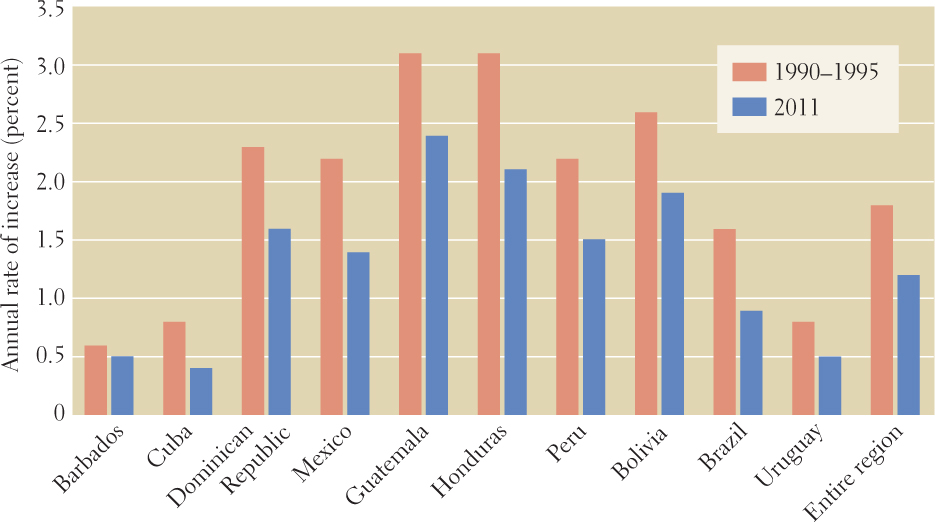

By 1990, improved living conditions (food, shelter, sanitation habits) and improved education and medical care, plus urbanization, all contributed to declining rates of natural increase, as shown in Figure 3.21; however, because 28 percent of the region’s population is under age 15, even if couples choose to have only one or two children, the population will continue to grow as this large group reaches the age of reproduction. Nonetheless, population projections for the year 2050 were recently revised downward from 778 million to 746 million. Though significantly lower than previous forecasts, for a region struggling to increase living standards, supplying 150 million more people with food, water, homes, schools, and hospitals will be a challenge.

By the 1980s, migration out of the region and lower birth rates were further curbs to population growth. Now the region is undergoing a demographic transition (see Figure 1.10). Between 1975 and 2011, the annual rate of natural increase for the entire region fell from about 1.9 percent to 1.2 percent—a rate of growth now equal to the world average. However, the low death rate continues to contribute to population growth in most of the region.

HIV-AIDS

The global epidemic of HIV-AIDS is now taking a significant toll on populations throughout this region. In 2009, about 2.9 million people were HIV-positive. Of these, at least 60,000 were children. Some Caribbean islands have the highest HIV-AIDS infection rates outside sub-Saharan Africa, where the rate is 5 percent of the population. On the impoverished island of Haiti, 2.2 percent of the age 15–49 population has HIV-AIDS; in the Bahamas, 3 percent does. In most of the Caribbean, however, aggressive education programs about HIV, along with high literacy rates and the relatively high status of women, are limiting the number of infections.

The Venezuelan journalist Silvana Paternostro, in her book In the Land of God and Man: Confronting Our Sexual Culture (1998), argues that across Middle and South America, cultural practices discourage the open discussion of sex. Men are rarely expected to be monogamous, and many visit prostitutes, exposing their wives and any children they might bear to infection. A wife would be loath to ask her husband to use a condom. Drug use is also a significant factor in the spread of HIV.

While this general inclination to keep all kinds of sexual relationships in the closet persists, over the last decade attitudes have begun to change, due in part to television novellas that have explored many formerly taboo sexual issues, including HIV and especially homosexuality. In 2010, Argentina legalized gay marriage, as did Mexico City.

Human Well-Being

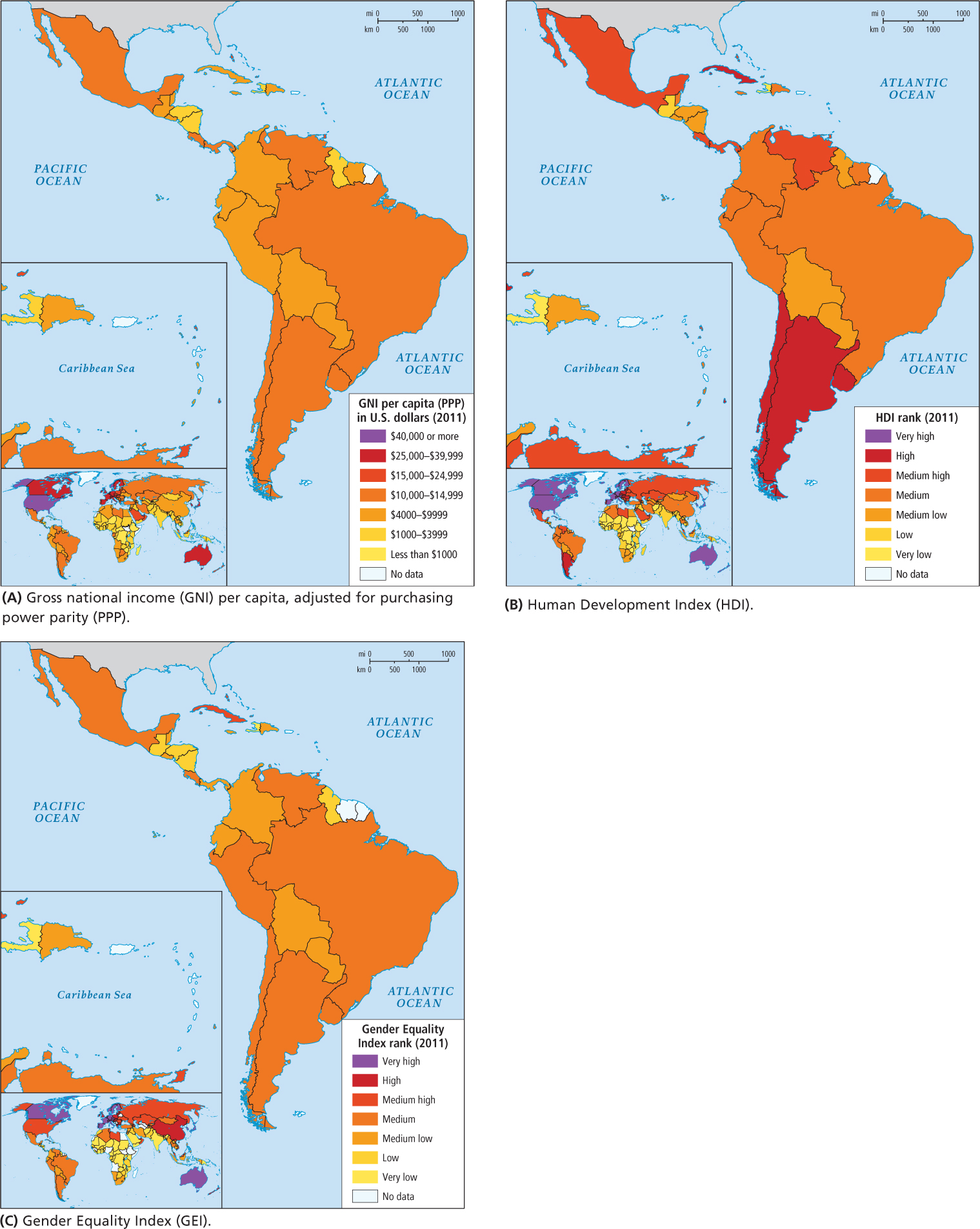

The wide disparities in wealth that are a feature of life in Middle and South America have been discussed above. Too often, development efforts linked to urbanization and globalization have only increased the gap between rich and poor. Each of the three maps in Figure 3.22 shows one of the various indicators of well-being used by the United Nations to show how countries are doing in providing a decent life for their citizens.

Map A in Figure 3.22 is of average GNI per capita (PPP). It is immediately apparent that no country in this region falls in the two highest categories, and just a few islands in the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and Antigua and Barbuda) fall into the third-highest category. As discussed, most of the Caribbean is in the global middle class, with one major exception, Haiti. Across the mainland, only Mexico, Panama, Venezuela, Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile have an average per capita GNI between U.S.$10,000 and U.S.$14,999. All other countries in the region have average per capita GNIs that are less than $9999, many of them significantly less. Also, most of these countries have rather wide disparities in wealth (see Table 3.2) that are masked on a map like this. In Brazil, for example, the most affluent 10 percent have incomes that are 41 times greater than the bottom 10 percent, and in actuality, some Brazilians survive on less than $1000 a year, while others have incomes well over $100,000 per year.

Map B in Figure 3.22, which charts the HDI rank for all countries in the region, shows that most countries rank in the medium and high ranges in providing the basics (education, health care, and income) for their citizens. The global inset map confirms this mid-range status for Middle and South America. Most of Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia rank lower, while North America, Europe, Australia, Japan, and South Korea rank higher. Much of East Asia, Russia, and some of the post-independent states of the former Soviet Union rank in the same range as Middle and South America. Of course, the UN HDI is a countrywide index and does not give any indication of how well-being is distributed within a given country. On this map and the GNI map, the countries of the Central American isthmus stand out as poorer than Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Democratizing Role of the Internet

Internet access and use is spreading rapidly, aiding small businesses, making human rights monitoring more feasible, and increasing employment possibilities for many. The Internet helped the Zapatistas of Mexico and the MST of Brazil get their message out to the rest of the world. Perhaps the most important advantages of expanded Internet access are the opportunities it provides for skills training, for enhancing schools’ curricula, and for higher education.

Map C in Figure 3.22, which shows the regional patterns of gender equality, illustrates that the region of Middle and South America does not yet begin to approach gender equality in pay or access to opportunity; it ranks even lower than some parts of Africa in terms of gender equality. The fact that Paraguay, Bolivia, and Colombia have higher GEI ranks than do Brazil and Argentina—and much higher than Chile and Mexico and others shown in yellow—does not mean that pay for women is higher there (compare with Map A); it only indicates that pay for men and women is somewhat closer to being equitable.

Rapid Regional Expansion of Internet Use

Overall, Middle and South America are more advanced in terms of information technology than are many other developing regions of the world—a fact that could open up many new economic opportunities for the region in the near future. Brazil ranks fifth in the world in terms of total number of Internet users, and has two world-class technology hubs in the environs of São Paulo. Mexico, with 36.9 percent of its population connected, has recently launched a program to give its citizens access to training and higher education via the Internet (Figure 3.23). Similar efforts throughout the region are part of a long-term shift, especially in urban areas, toward more technologically sophisticated and better-paid service sector employment. In 2000, only 3.2 percent of the region’s population used the Internet, but that figure had risen to nearly 40 percent by 2010, an increase of more than 1000 percent.

Cultural Diversity

The region of Middle and South America is culturally complex because many distinct indigenous groups were already present when the Europeans arrived, and then many cultures were introduced during and after the colonial period. From 1500 to the early 1800s, some 10 million people from many different parts of Africa were brought to plantations on the islands and in the coastal zones of Middle and South America. After the emancipation of African slaves in the British-controlled Caribbean islands in the 1830s, more than half a million Asians were brought there from India, Pakistan, and China as indentured agricultural workers. Their cultural impact remains most visible in Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and the Guianas. In some parts of Mexico, Central America, the Amazon Basin, and the Andean Highlands, indigenous people have remained numerous. To the unpracticed eye, they may appear little affected by colonization, but this is not the case.

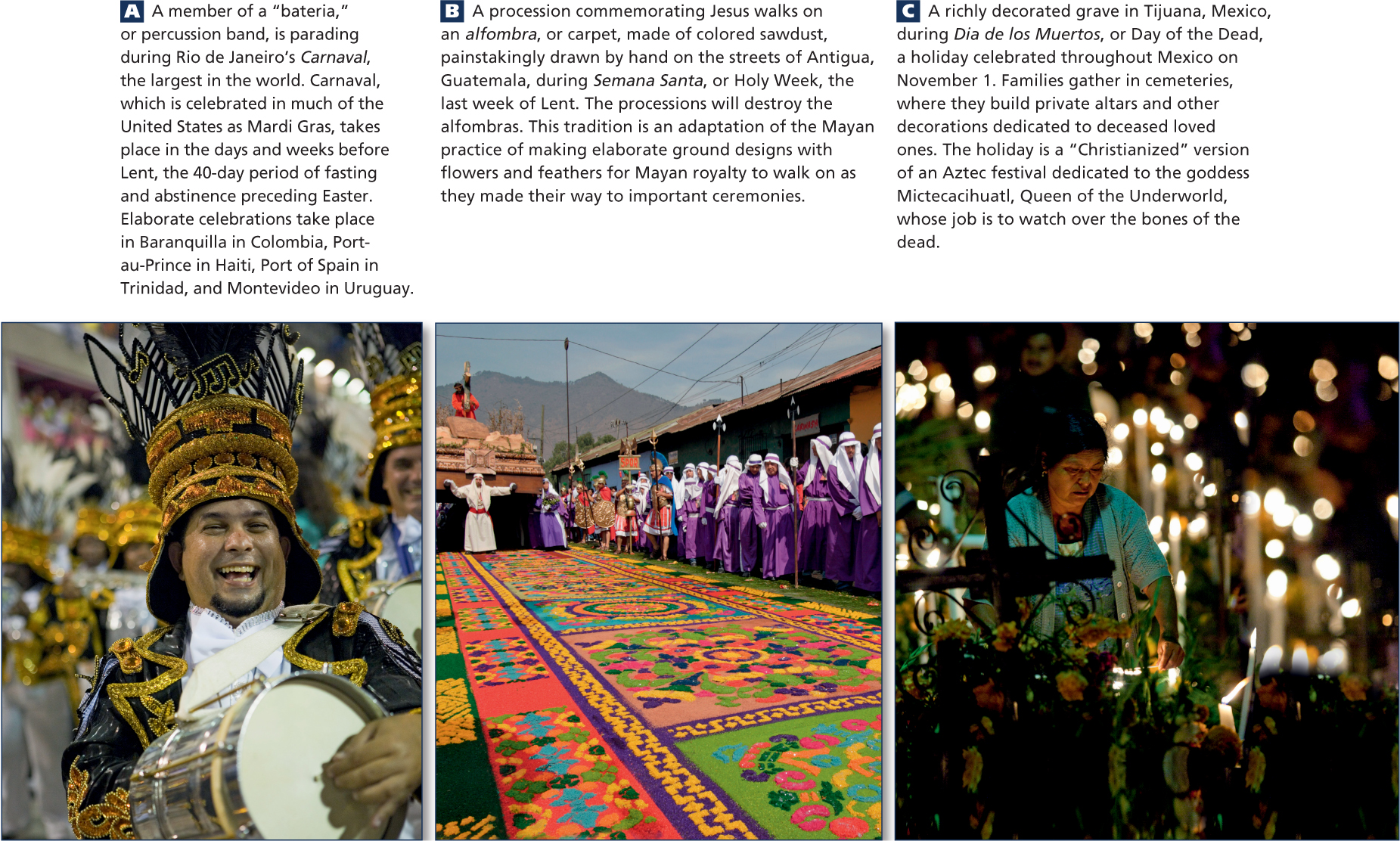

Today in the Caribbean and along the east coast of Central America as well as the Atlantic coast of Brazil, mestizos (people who have a mixture of African, European, and some indigenous ancestry) make up the majority of the population (Figure 3.24). Some of the most colorful festivals in the Americas—especially versions of Mardi Gras and Carnival—are based on a melding of cultural practices from these three heritages (see Figure 3.24A). In some areas, such as Argentina, Chile, and southern Brazil, people of Central European descent are also numerous. The Japanese, though a tiny minority everywhere in the region, increasingly influence agriculture and industry, especially in Brazil, the Caribbean, and Peru. Alberto Fujimori, a Peruvian of Japanese descent, campaigned on his ethnic “outsider” status to become president of Peru during a time of political upheaval.

3.24a Courtesy Viviane Ponti/Lonely Planet Images/Getty Images, 3.24b Courtesy Danita Delimont/Gallo Images/Getty Images, 3.24c Courtesy Claudio Cruz/LatinContent/Getty Images

acculturation adaptation of a minority culture to the host culture enough to function effectively and be self-supporting

assimilation the loss of old ways of life and the adoption of the lifestyle of another culture

Race and the Social Significance of Skin Color

People from Middle and South America, especially those from Brazil, often proudly claim that race and color are of less consequence in this region than in North America. They are only partially right. In all of the Americas, skin color is now less associated with status than in the past. A person of any skin color, by acquiring an education, a good job, a substantial income, the right accent, and a high-status mate, may become recognized as upper class.

Nevertheless, the ability to erase the significance of skin color through one’s actions is not quite the same as race having no significance at all. Overall, those who are poor, less educated, and of lower social standing tend to have darker skin than those who are educated and wealthy. And while there are poor people of European descent throughout the region, most light-skinned people are middle and upper class. Indeed, race and skin color have not disappeared as social factors in the region. In some countries—Cuba, for example, where overt racist comments are socially unacceptable—it is common for a speaker to use a gesture (tapping his or her forearm with two fingers) to indicate that the person referred to in the conversation is of African descent.

The Family and Gender Roles

extended family a family that consists of related individuals beyond the nuclear family of parents and children

The arrangement of domestic spaces and patterns of socializing illustrate these strong family ties. Families of adult siblings, their mates and children, and their elderly parents frequently live together in domestic compounds of several houses surrounded by walls or hedges. Social groups in public spaces are most likely to be family members of several generations rather than unrelated groups of single young adults or married couples, as would be the case in Europe or the United States. A woman’s best friends are likely to be her female relatives. A man’s social or business circles will include male family members or long-standing family friends.

marianismo a set of values based on the life of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, that defines the proper social roles for women in Middle and South America

Her husband, the official head of the family, is expected to work and to give most of his income to his family. Still, men have much more autonomy and freedom to shape their lives than women because they are expected to move about the larger community and establish relationships, both economic and personal. A man’s social network is considered just as essential to the family’s prosperity and status in the community as is his work.

machismo a set of values that defines manliness in Middle and South America

Many factors are transforming these traditional family and gender roles. With infant mortality declining steeply, couples are now having only two or three children instead of five or more. Moreover, because most people still marry young, parents are generally free of child-raising responsibilities by the time they are 40. Left with 30 or more years of active life to fill in other ways (life expectancies in the region average in the mid-70s), middle-aged mothers and grandmothers are increasingly working in urban factory or office jobs that put to use the organizational and problem-solving skills they developed while managing a family. Employment outside the home allows women greater independence and helps them contribute to the needs of the extended family. Some women are even moving into high-level jobs, such as management positions, professorships, and positions that traditionally went to men—for example, the presidencies of Chile, Argentina, and Brazil. Many of the traditional cultural restrictions on the mobility of women have been relaxed, with the result that women are better able to use their talents and abilities to contribute economically and socially to family well-being.

Migration and Urbanization

Geographic Insight 6

Gender: Traditional gender roles are changing as women work outside the home and manage families while many men are migrating to other places for work. Also, urbanization is reducing the influence of extended families, opening the door for many types of social change.

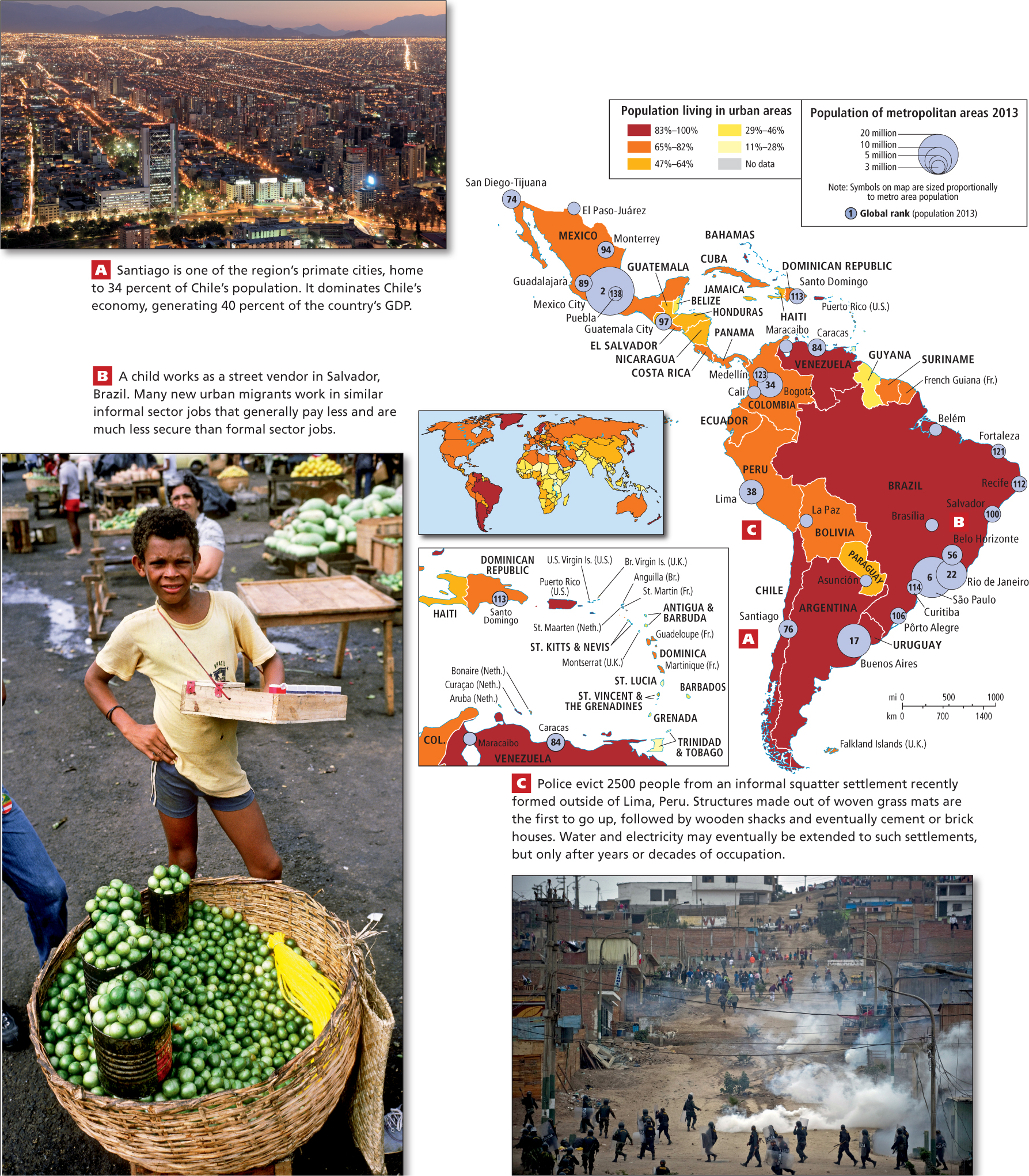

primate city a city, plus its suburbs, that is vastly larger than all others in a country and in which economic and political activity is centered

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization in Middle and South America, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What about this picture suggests that there may be considerable wealth in Santiago?

What about this picture suggests that there may be considerable wealth in Santiago?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why might work in the informal economy be considered insecure?

Why might work in the informal economy be considered insecure?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

All of the following are defining characteristics of "informal" squatter settlements except

All of the following are defining characteristics of "informal" squatter settlements except

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The concentration of people into just one or two large cities in a country leads to uneven spatial development and to government policies and social values that favor the largest urban areas. Wealth and power are concentrated in one place, while distant rural areas, and even other towns and cities, have difficulty competing for talent, investment, industries, and government services. Many provincial cities languish as their most educated youth leave for the primate city.

Brain Drain

brain drain the migration of educated and ambitious young adults to cities or foreign countries, depriving the communities from which the young people come of talented youth in whom they have invested years of nurturing and education

Urban Landscapes

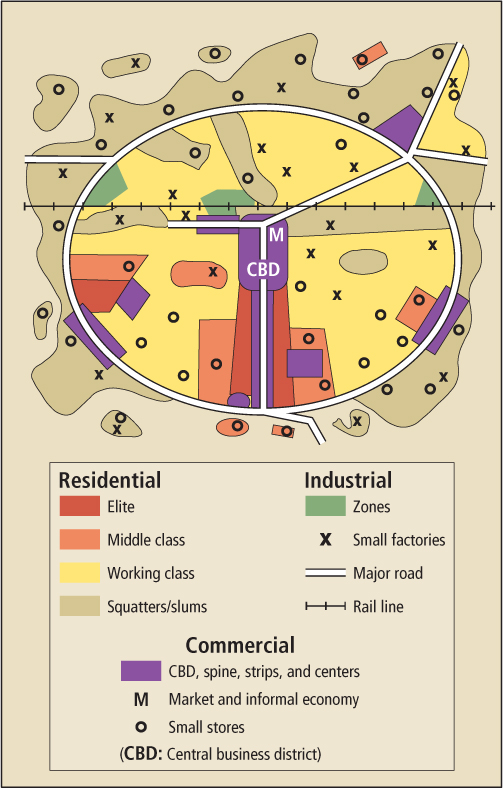

A lack of planning to accommodate the massive rush to the cities has created urban landscapes that are very different from the common U.S. pattern. In the United States, a poor, older inner city is usually surrounded by affluent suburbs, with clear and planned spatial separation of residences by income as well as separation of residential, industrial, and commercial areas. In Middle and South America, by contrast, both affluent and working-class areas have become unwilling neighbors to unplanned slums filled with poor migrants. Too destitute even to rent housing, these “squatters” occupy parks and small patches of vacant urban land wherever they can be found, as depicted in the diagram in Figure 3.26.

Unplanned Neighborhoods

favelas Brazilian urban slums and shantytowns built by the poor; called colonias, barrios, or barriadas in other countries

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why are favelas often located on steep hills, and why do residents often store water on their roofs?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The squatters frequently are enterprising people who work hard to improve their communities. They often organize to press governments for social services. Some cities, such as Fortaleza in northeastern Brazil, even contribute building materials so that favela residents can build more permanent structures with basic indoor plumbing. Over time, as shacks and lean-tos are transformed through self-help initiatives into crude but livable suburbs, the economy of favelas can become quite vibrant, with much activity in the informal sector. Housing may be intermingled with shops, factories, warehouses, and other commercial enterprises. Favelas and their counterparts can become centers of pride and support for their residents, where community work, folk belief systems, crafts, and music (for example, Favela Funk) flourish. Many of the best steel bands of Port of Spain, Trinidad, have their homes in the city’s shantytowns.

VIGNETTE

Favelas are everywhere in Fortaleza, Brazil. The city grew from 30,000 to 300,000 people during the 1980s. By 2006, there were more than 3 million residents, most of whom had fled drought and rural poverty in the interior of the country. City parks of just a square block or two in middle-class residential areas were suddenly invaded by squatters. Within a year, 10,000 or more people were occupying crude, stacked concrete dwellings in a single park, completely changing the ambience of the surrounding upscale neighborhood. In the early days of the migration, lack of water and sanitation often forced the migrants to relieve themselves on the street.

One day, while strolling on the Fortaleza waterfront, Lydia Pulsipher chanced to meet a resident of a beachfront favela who invited her to join him on his porch. There, he explained how he and his wife had come to the city 5 years before, after being forced to leave the drought-plagued interior when a newly built irrigation reservoir flooded the rented land their families had cultivated for generations. With no way to make a living, they set out on foot for the city. In Fortaleza, they constructed the building they used for home and work from objects they collected along the beach. Eventually they were able to purchase roofing tiles, which gave the building an air of permanency. At the time of the visit, he maintained a small refreshment stand and his wife a beauty parlor that catered to women from the beach settlements. [Source: Lydia Pulsipher’s field notes. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Planned Elite Landscapes

urban growth poles locations within cities that are attractive to investment, innovative immigrants, and trade, and thus attract economic development like a magnet

Urban Transport Issues

Transportation in large, rapidly expanding urban areas with millions of poor migrants can be a special challenge. Favelas are often on the urban fringes, far from available low-skill jobs and ill-served by roads and public transport (see Crowley’s model, Figure 3.26). Workers must make lengthy, time-consuming, and expensive commutes to jobs that pay very little. The entire urban population gets caught up in endless traffic jams that cripple the economy and pollute the environment. Rapid growth seems to have outstripped the capacities of even the most enlightened urban planning.

Yet the southern Brazilian city of Curitiba has carefully oriented its expansion around a master plan (dating from 1968) that includes an integrated transportation system funded by a public-private collaboration. Eleven hundred minibuses making 12,000 trips a day bring 1.3 million passengers from their remote neighborhoods to terminals, where they meet express buses to all parts of the city. The large pedestrian-only inner-city area is a boon for merchants because minibus commuters spend time shopping rather than looking for parking. Being able to get to work quickly and cheaply has helped the poor find and keep jobs. The reduced use of cars means that emissions and congestion are lowered and urban living is more pleasant.

Gender and Urbanization

Interestingly, rural women are just as likely as rural men to migrate to the city. This is especially true when employment is available in foreign-owned factories that produce goods for export. Companies prefer women for such jobs because they are a low-cost and usually passive labor force. Factors that push people out of rural areas—for instance, the shift toward green revolution agriculture—often affect women intensely because women are rarely considered for jobs such as farm-equipment operators or mechanics. In urban areas, unskilled migrant women and children usually find work as street vendors (see Figure 3.25B) or domestic servants.

Male urban migrants tend to depend on short-term, low-skill day work in construction, maintenance, small-scale manufacturing, and petty commerce. Many work in the informal economy as street vendors, errand runners, car washers, and trash recyclers—and some turn to crime. In an urban context, both men and women sorely feel the loss of family ties and village life; the chances for recreating the family life they once knew are extremely low.

Once relocated to a city, migrant families may disintegrate because of extreme poverty and malnutrition, long commutes for both working parents, and poor quality of day care for children. At too young an age, children are left alone or sent into the streets to scavenge for food or to earn money for the family.

Religion in Contemporary Life

Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and indigenous beliefs are found across the region, but the majority of the people are at least nominal Christians, most of them Roman Catholic. While the Roman Catholic Church remains highly influential and relevant to the lives of believers, it has had to contend both with popular efforts to reform it and with increasing competition from other religious movements. From the beginning of the colonial era, the church was the major partner of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial governments. It received extensive lands and resources from colonial governments, and in return built massive cathedrals and churches throughout the region, sending thousands of missionary priests to convert indigenous people. The Roman Catholic Church encouraged the poor converts to accept their low status, obey authority, and postpone rewards for their hard work until heaven.

Poor people throughout the region embraced the faith, and they still make up the majority of the church members. Many are indigenous people who put their own spin on Catholicism, creating multiple folk versions of the Mass with folk music, greater participation of women in worship services, and interpretations of Scripture that vary greatly from European versions. A range of African-based belief systems (Candomblé, Umbanda, Santería, Obeah, and Voodoo) combined with Catholic beliefs is found in Brazil, northern South America, and Middle America and the Caribbean—wherever the descendants of Africans have settled. These African-based religions have attracted adherents of European or indigenous backgrounds as well, especially in urban areas.

populist movements popularly based efforts, often seeking relief for the poor

liberation theology a movement within the Roman Catholic Church that uses the teachings of Jesus to encourage the poor to organize to change their own lives and to encourage the rich to promote social and economic equity

The legacy of liberation theology is now fading. At its height in the 1970s and early 1980s, liberation theology was the most articulate movement for region-wide social change. It had more than 3 million adherents in Brazil alone. But the Vatican then objected to this popularized version of Catholicism, and today its influence is diminished. The first pope from the Americas, Francis of Argentina, while critical of capitalism and an advocate for the poor, eschews connections with liberation theology, which now must compete with newly emerging evangelical Protestant movements.  79. POPE OPENS TOUR OF LATIN AMERICA IN BRAZIL

79. POPE OPENS TOUR OF LATIN AMERICA IN BRAZIL

evangelical Protestantism a Christian movement that focuses on personal salvation and empowerment of the individual through miraculous healing and transformation; some practitioners preach to the poor the “gospel of success”—that a life dedicated to Christ will result in prosperity for the believer

The movement is charismatic, meaning that it focuses on personal salvation and empowerment of the individual through miraculous healing and psychological transformation. Evangelical Protestantism is not hierarchical in the same way as the Roman Catholic Church, and there is usually no central authority; rather, there are a host of small, independent congregations led by entrepreneurial individuals who may be either male or female.

Perhaps two of the most important contributions of evangelical Protestantism are the focus (as in Umbanda and other African-based religions) on helping people, especially urban migrants, cope with modern life; and the emphasis placed on involving women in leadership roles in church activities and services.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 5Population A population explosion occurred during the early twentieth century as improved health care lowered death rates.

Geographic Insight 5Population A population explosion occurred during the early twentieth century as improved health care lowered death rates. Birth rates started to decline by the mid-1980s as more women began to delay childbearing in order to pursue work outside the home. At the same time, populations became more urbanized, which reduced the need for large families to operate farms.

Birth rates started to decline by the mid-1980s as more women began to delay childbearing in order to pursue work outside the home. At the same time, populations became more urbanized, which reduced the need for large families to operate farms. Rapid growth of Internet use is part of a long-term shift toward more technologically sophisticated service sector employment.

Rapid growth of Internet use is part of a long-term shift toward more technologically sophisticated service sector employment. Gender roles in the region have been strongly influenced by the Catholic Church through the ideals of marianismo and machismo.

Gender roles in the region have been strongly influenced by the Catholic Church through the ideals of marianismo and machismo. Geographic Insight 6Gender Middle-aged women are increasingly working in factory or office jobs once dominated by men; they put to use the organizational and problem-solving skills developed while supervising a family.

Geographic Insight 6Gender Middle-aged women are increasingly working in factory or office jobs once dominated by men; they put to use the organizational and problem-solving skills developed while supervising a family. Urbanization is putting new pressures on the extended family, opening up new opportunities for women and fostering new belief systems.

Urbanization is putting new pressures on the extended family, opening up new opportunities for women and fostering new belief systems. Evangelical Protestantism came to the region from North America and is now the fastest-growing religious movement in the region.

Evangelical Protestantism came to the region from North America and is now the fastest-growing religious movement in the region.