The Caribbean

Much of the Caribbean has a strong record of fostering human well-being, but visitors are often unaware of this focus and tend to be struck by the failure of the ramshackle, lived-in landscapes of the islands to match the glamorous expectations inspired by the tourist brochures and television ads. Because Caribbean tourists are usually (and unnecessarily) isolated in hotel enclaves or on cruise ships, glimpsing only tiny swatches of island settlements through green foliage, they rarely learn that the humble houses, garden plots, and quaint, rutted, narrow streets mask social and economic conditions that are supportive of a modest but healthy and productive way of life.

Political, Social, and Economic Change

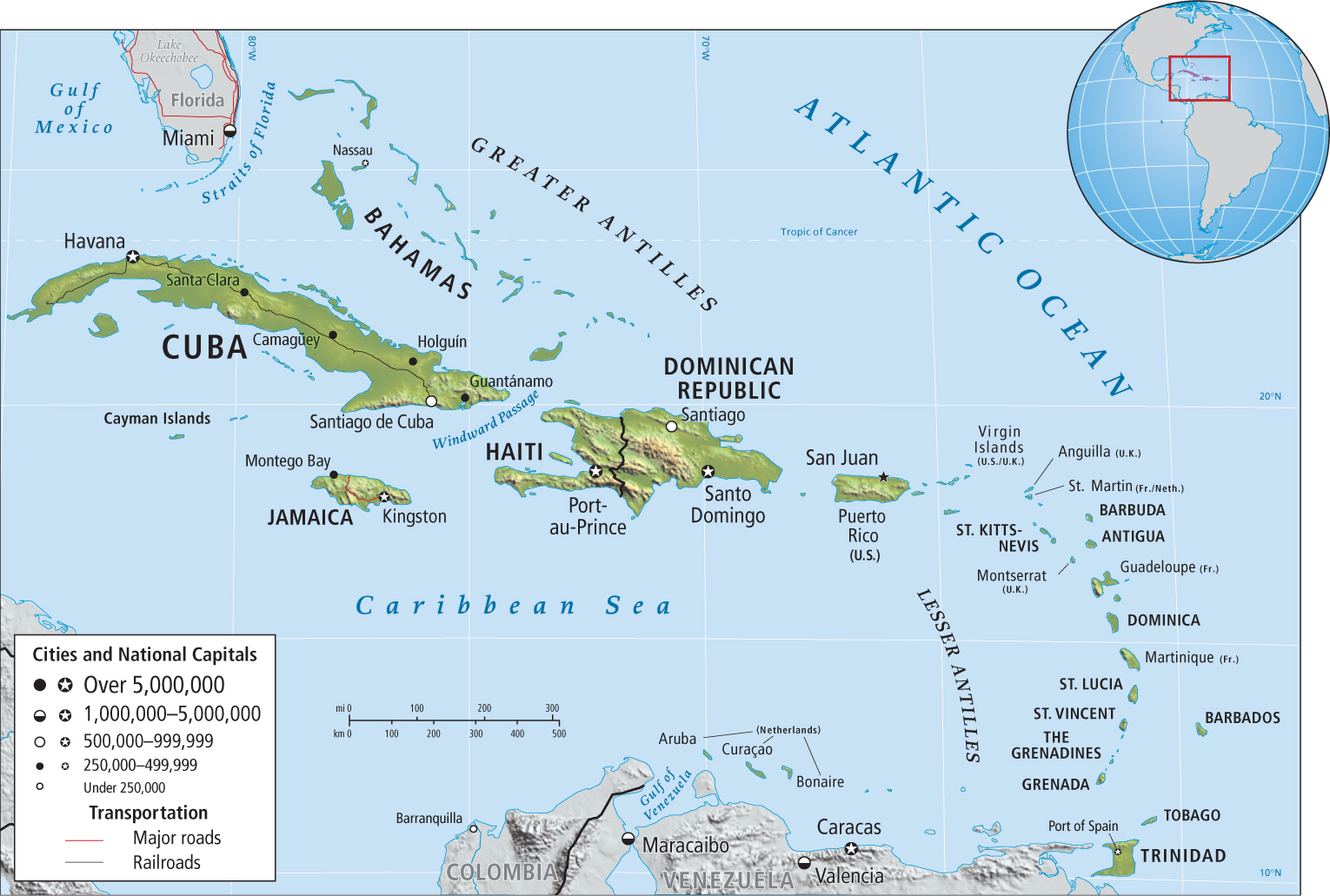

Over the past half-century, most of the island societies have emerged from colonial status to become independent, self-governing states (Figure 3.28). With the exception of Haiti and parts of the Dominican Republic, these islands are no longer the poverty-stricken places they were 40 years ago. Rather, they are managing to provide a reasonably high quality of life for their people. Children go to school, and literacy rates for all but the elderly average close to 95 percent. There is basic health care: mothers receive prenatal care, nearly all babies are born in hospitals, infant mortality rates are low, and diseases of aging are competently treated. Life expectancy is in the 70s, and people are choosing to have fewer children; the overall rate of population increase for the Caribbean is the lowest in Middle and South America. A number of Caribbean islands rank high on the Human Development Index, and some (the Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, and Trinidad and Tobago) do particularly well in making opportunities available to women. Returned emigrants often say that the quality of life on their home Caribbean islands actually exceeds that of far more materially endowed societies because life is enhanced by strong community and family support. And, of course, there is the healthful and beautiful natural environment.

Island governments continually search for ways to turn former plantation economies, once managed from Europe and North America, into more self-directed, self-sufficient, and flexible entities that can adapt quickly to the perpetually changing markets of the global economy. To guide their islands toward a specialized activity such as tourism is tempting, but island economists (one, Sir Arthur Lewis, won the Nobel Prize) are wary of the dependence and vulnerability that too much specialization can bring. When plantation cultivation of sugar, cotton, and copra (dried coconut meat) died out in the 1950s and 1960s, some islands turned to producing “dessert” crops, such as bananas and coffee, which they sold for high prices under special agreements with the countries that once held them as colonies. Now these protections are disappearing as free market agreements in the European Union make such special arrangements illegal. Other island countries turned to the processing of their special resources (petroleum in Trinidad and Tobago, bauxite in Jamaica), the assembly of such high-tech products as computer chips and pharmaceuticals (in St. Kitts and Nevis), or the processing of computerized data (in Barbados). Most islands combine one or more of these strategies with tourism development.

In 2011, tourism and related activities contributed at least 60 percent of the gross national product in island countries such as Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, the Bahamas, and St. Martin. In most years, Antigua and Barbuda (population 85,000) hosts more than four times its population in tourists, and St. Martin (population 30,000) hosts 33 times its population. Heavy borrowing to import food as local agriculture declines and to build hotels, airports, water systems, and shopping centers for tourists has left some islands with debts many times their income. Furthermore, there is a special stress that comes from dealing perpetually with hordes of strangers, especially when they act in ways that violate local mores and make erroneous assumptions about the state of well-being in the islands (see Figure 3.22B).

Host countries consider tourism difficult to regulate, in part because it is a complex multinational industry controlled by external interests in North America and Europe, such as travel agencies, airlines, and the investors needed to fund the construction of hotels, resorts, restaurants, and golf courses. Caribbean cruise ships now routinely bring several thousand passengers into small port cities such as Castries or Soufrière in St. Lucia. Large ships are troublesome to accommodate because of their enormous size and the large numbers of day visitors (6000) they discharge into small ports. The environmental pollution these ships create, such as garbage and sewage dumping, is hard for tiny countries to regulate and punish. To exercise more control over the industry, some islands are looking for tourists who will stay on shore for a week or more and show a more informed interest in island societies. Ecotourism, sport tourism (such as small-boat sailing), and special-interest seminar tourism (such as cooking, art, yoga, and physical fitness retreats) are three variations that better suit the Caribbean environment and are low-density alternatives to the “sand, sea, and sun” mass tourism that presently brings the majority of visitors to the region.

Cuba and Puerto Rico Compared

Cuba and Puerto Rico are interesting to compare because they shared a common history until the 1950s, then diverged starkly. North American interests dominated both islands after the end of Spanish rule around 1900. U.S. investors owned plantations, resort hotels, and other businesses on both islands. To protect their interests, the U.S. government influenced local dictatorial regimes to keep labor organization at a minimum and social unrest under control. By the 1950s, poverty was widespread in both Cuba and Puerto Rico. Infant mortality was above 50 per 1000 births, and most people worked as agricultural laborers. Then each island took a different course toward social transformation. In 1959, Cuba went through a Communist revolution under the leadership of Fidel Castro; meanwhile, Puerto Rico underwent a more gradual capitalist metamorphosis into a high-tech manufacturing center.

Cuba

Since Castro seized control (see Figure 3.18C), Cuba has dramatically improved the well-being of its general population in all physical categories of measurement (life expectancy, literacy, and infant mortality). By 1990, it had a solid human well-being record despite its persistently rather low GNI per capita (see Figure 3.22). Cuba thus proved that, once the requisite investment in human capital is made, poverty and social problems are not as intractable as some people had thought. Unfortunately, Cuba’s successes are not replicable elsewhere in the region, first, because Cuba has been extremely politically repressive, forcing out the aristocracy, jailing and executing dissidents. Second, Cuba has been inordinately dependent on outside help to achieve its social revolution. Until 1991, the Soviet Union was Cuba’s chief sponsor. It provided cheap fuel and generous foreign aid and bought Cuba’s main export crop, sugar, at artificially high prices.

With the demise of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s economy declined sharply during what became known as the Special Period, when all Cubans were asked to make major sacrifices and slash the use of food and fuel. To survive this economic crisis, Cuba opened its economy to outside, especially European, investment capital, to help redevelop its tourism industry. Medical tourism and pharmaceuticals are special emphases because early in the revolution, Castro invested in high-quality medical education and encouraged poor, young people to become scientists and doctors. More than 5000 patients, mostly from South America, come per year for cosmetic and other procedures. Canada has invested in joint biotech research on hepatitis and cancer drugs with Cuban medical scientists. In exchange for Cuban pharmaceuticals, high-tech medical equipment, and the services of medical social workers and several thousand medical doctors, Venezuela furnishes Cuba with at least 100,000 barrels of oil a day (2012). (Oil was discovered off Cuba’s north shore in 2012, and numerous oil exploration firms from around the world are vying for development rights.)

Leisure tourism remains Cuba’s biggest earner. Cuban tourism grossed an estimated $2 billion in 2011, hosting 3 million visitors, mostly Canadians and Europeans, who spent a week or more at luxury beach resorts. Despite growing earnings from these medical and tourism industries, access to this income is restricted for ordinary Cubans; for them, consumer goods and even food remain in short supply.

75. CUBANS UNCERTAIN ABOUT FUTURE BUT MANY CRAVE CHANGE

75. CUBANS UNCERTAIN ABOUT FUTURE BUT MANY CRAVE CHANGE

76. CUBANS STRUGGLE IN PROVINCE RICH IN TOBACCO, TOURISM

76. CUBANS STRUGGLE IN PROVINCE RICH IN TOBACCO, TOURISM

77. CUBANS CAUGHT BETWEEN COMMUNIST PAST, UNCERTAIN FUTURE

77. CUBANS CAUGHT BETWEEN COMMUNIST PAST, UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Political relations between the Castro regime and successive U.S. administrations remained on Cold War terms from 1961 to 2009, when President Obama loosened the rules on travel to Cuba and proposed wider changes in U.S. relations with Cuba. So far, the U.S. Congress has refused to cancel the Helms-Burton Act, adopted in 1996 and aimed at stopping all trade with Cuba. However, governments in Europe and the Americas ignore the Helms-Burton Act. They continue to trade with and invest in Cuba.

Another contentious issue between Cuba and the United States is the naval base at Guantánamo in far southern Cuba, on territory held by the United States since the Spanish-American War (1898). This base gained international notoriety after 2002, when the United States, under the Bush administration, began using it, counter to the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war, to indefinitely detain prisoners captured in Afghanistan and elsewhere who were suspected of having links to terrorism. President Obama announced plans to close Guantánamo, but as of mid-2013, he had not done so.

Puerto Rico

In the 1950s, Puerto Rico began Operation Bootstrap, a government-aided program to transform the island’s economy from its traditional sugar plantation base to modern industrialism. Many international industries took advantage of generous tax-free guarantees and subsidies to locate plants on the island. Since 1965, this industrial sector has shifted from light to heavy manufacturing, from assembly plants to petroleum processing and pharmaceutical manufacturing. The Puerto Rican seaboard is heavily polluted, partly as a consequence of the chemicals released by these more recent industries.

Because Puerto Rico is a commonwealth within the United States and its people are U.S. citizens, many Puerto Ricans migrate to work in the United States. Their remittances, as well as the manufacturing jobs in Puerto Rico, have greatly improved living conditions on the island, but social investment by the U.S. government has also upgraded the standard of living. Many Puerto Ricans receive some sort of support from the federal government, including retirement benefits and health care. The infant mortality rate in 2009 was 8.8 per 1000 births, with life expectancy at 78 years (Cuba’s infant mortality rate was 4.7, with life expectancy also at 78 years). The connection with the United States helps Puerto Rico’s tourism and light-industry economy, but outside of San Juan, with its skyscraper tourist hotels, Puerto Rico’s landscape reflects stagnation: few interesting or well-paying jobs, an inadequate transportation system, little development at the community level, mediocre schools, and few opportunities for advanced training, all of which encourage migration to the mainland.

Puerto Ricans are split about how to improve their situation. Complete independence would bring pride and facilitate closer ties to Middle and South America; it would also help Puerto Rico retain the island’s Spanish linguistic and cultural heritage. Statehood for Puerto Rico, which some favor, would mean higher status in the United States, but it would also mean the end of tax holidays for U.S. companies based there, and thus the loss of Puerto Rico’s edge in attracting assembly plants, some of which are already moving to cheaper labor markets in Asia.

Haiti and Barbados Compared

Haiti and Barbados present another study in contrasts (Figure 3.29). During the colonial era, both were European possessions with plantation economies—Haiti a colony of France, and Barbados a colony of Britain. Yet they have had very different experiences, and today they are far apart in economic and social well-being. Haiti, though not without useful resources, is the poorest nation in the Americas, with a United Nations HDI rank of 158 out of 187. Barbados, by contrast, has one of the highest HDI rankings in the entire region (47), even though it has much less space, a higher population density than Haiti, and few resources other than its limestone soil, beaches, and people.

3.29a Courtesy Vanderlei Almeida/AFP/Getty Images, 3.29b Courtesy John Warburton-Lee/AWL Images/Getty Images

Haiti

At the end of the eighteenth century, Haiti had the richest plantation economy in the Caribbean. When Haitian slaves revolted against the brutality of the French planters in 1804, Haiti became the first colony in Middle and South America to achieve independence. Haiti’s early promise was lost, however, when the former slave-reformist leaders were overthrown by other former slaves who were violent and corrupt militarists. They neither reformed the exploitative plantation economy nor sought a new economic base. Under a long series of incompetent and avaricious authoritarian governments, the people sank into abject poverty, while the land was badly damaged by particularly wasteful, unprofitable plantation cultivation. In the middle of the twentieth century, a class-based reign of terror under François “Papa Doc” Duvalier (1957–1971) and his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” (1971–1986), pitted the mulatto elite against the black poor. They were followed by a series of weak leaders who promised social reform but delivered little.

Today, Haiti remains overwhelmingly rural, with widespread illiteracy, an infant mortality rate of 57 per 1000 births (Barbados’s rate is 12), and painfully few jobs. Multinational corporations opened maquiladora-like assembly plants, employing primarily young women, but the plants have not flourished and they drew thousands in from the countryside for whom there were no jobs. Although minerals such as bauxite, copper, and tin exist in Haiti, cost-effective development of these resources is not yet possible. Haiti’s lands are deforested and eroded and subject to disastrous flooding (see Figure 3.10C). Traditional agriculture, potentially quite productive, has been defeated by extreme environmental deterioration. Efforts to establish democracy have repeatedly devolved into violence (see the Figure 3.18 map). Since the early 1990s—long before four hurricanes struck the island in 2008 and a massively devastating earthquake destroyed nearly all structures and killed 200,000 to 250,000 people in January 2010—the United Nations has maintained peacekeeping troops in Haiti, and several humanitarian aid organizations, in addition to the U.S. government, run programs there. Earthquake aid rendered by an unprecedented number of countries from across the globe may at last begin to make a difference, in part because the scope of the disaster may have weakened sources of resistance to change.  58. REBUILDING EFFORTS IN HAITI SHIFT TO EDUCATION

58. REBUILDING EFFORTS IN HAITI SHIFT TO EDUCATION

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Life in the Caribbean Is good

With the exception of Haiti, close examination of Caribbean landscapes and ways of daily life reveal a particularly healthful and rewarding, if not affluent, standard of living. Caribbean women hold region-wide leadership positions. Caribbean intellectuals have won several Nobel Prizes. At the 2012 Olympics in London, the Caribbean fielded the largest percentage of elite track stars, male and female.

Barbados

Tiny but far more prosperous, Barbados has fewer natural resources and is more than twice as crowded as Haiti. With just 166 square miles (430 square kilometers), Barbados has 1684 people per square mile (650 per square kilometer); by contrast, Haiti, with 10,700 square miles (27,800 square kilometers) has only 850 people per square mile (328 per square kilometer). Although both Haiti and Barbados entered the twentieth century with large, illiterate, agricultural populations, their development paths have diverged sharply. In 2012, two-thirds of Haitians were still agricultural workers, and only half were able to read and write. Barbados, on the other hand, now has 100 percent literacy and a diversified economy that includes tourism, sugar production, remittances from migrants, information processing, offshore financial services, and modern industries that sell products throughout the Caribbean. Barbados’s present prosperity is explained by the fact that its citizens successfully pressured the British government to invest in the people and infrastructure of its colony before giving it independence in 1966. Barbadians hold jobs requiring sophisticated skills; they are well educated and well fed, and most are homeowners. Furthermore, the Barbadian government and private businesspeople constantly seek new employment options for the citizens and occupy a central role in Caribbean economic and social development.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Sun, sand, and sea tourism is the main source of economic well-being in most of the Caribbean subregion, but these island nations are working to adopt more flexible and diversified economic strategies in the globalizing world.

Sun, sand, and sea tourism is the main source of economic well-being in most of the Caribbean subregion, but these island nations are working to adopt more flexible and diversified economic strategies in the globalizing world. Over the past half-century, many of the island societies have emerged from colonial status to become independent, self-governing states, some more democratic than others. Several Caribbean islands are not yet independent, self-governing states; a few remain colonies, and others are states or entities of France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, or the United States.

Over the past half-century, many of the island societies have emerged from colonial status to become independent, self-governing states, some more democratic than others. Several Caribbean islands are not yet independent, self-governing states; a few remain colonies, and others are states or entities of France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, or the United States. The poverty and social dysfunction of Haiti is atypical of the Caribbean and is the result of a long series of circumstances and disasters, only some of which could have been prevented.

The poverty and social dysfunction of Haiti is atypical of the Caribbean and is the result of a long series of circumstances and disasters, only some of which could have been prevented.