Mexico

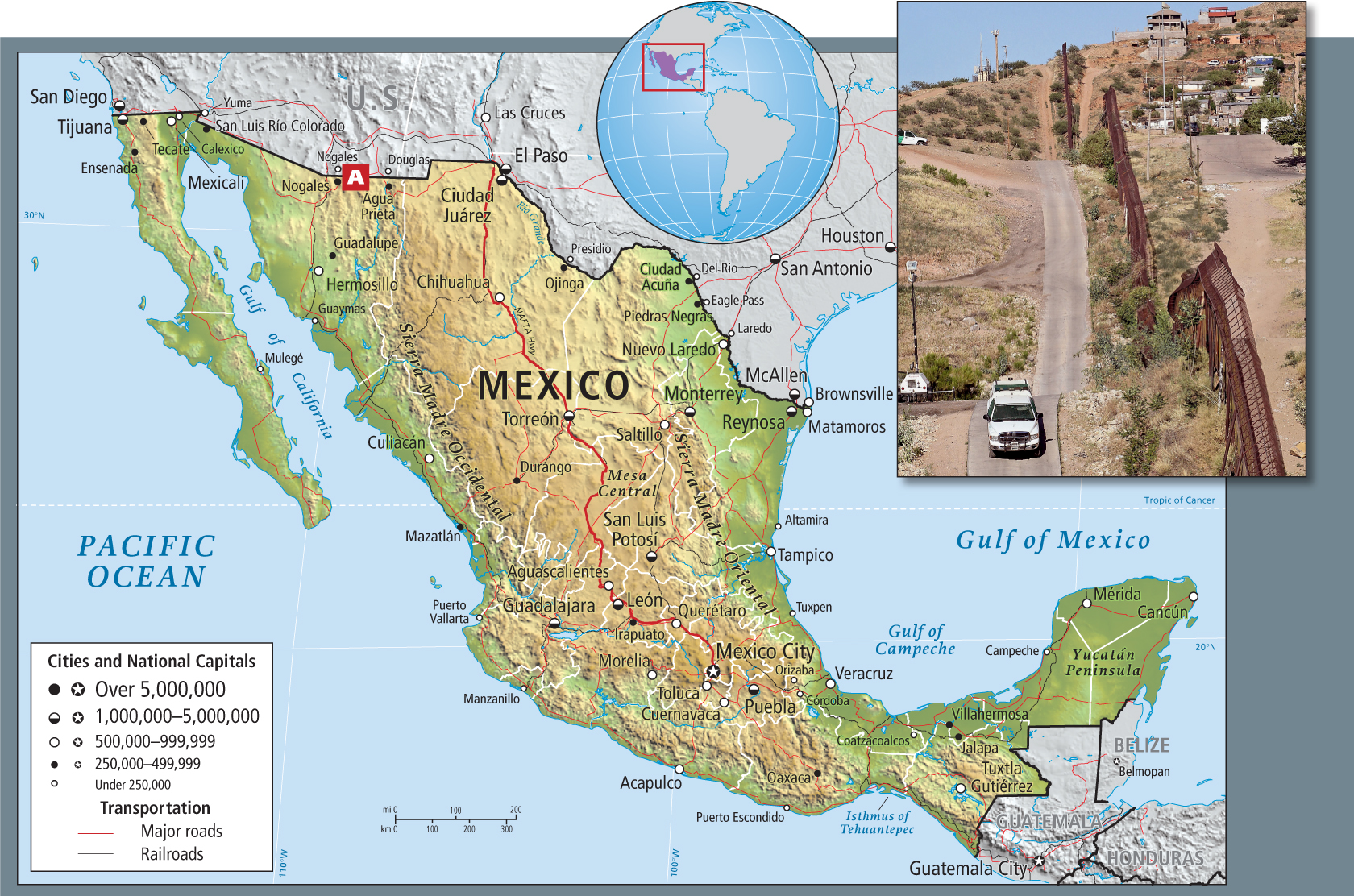

Mexico is working toward becoming a reasonably well-managed, middle-income democracy (Figure 3.30), but the situation is fragile; the economic recession, corruption, and drug-cartel violence threaten Mexico’s future (see Figure 3.18A, Figure 3.19, and the discussion). Most of the efforts to achieve economic success and political stability are linked in some way to Mexico’s relationship with the United States, its main trade partner. The integration of the Mexican, U.S., and Canadian economies has proceeded rapidly since NAFTA became official in the mid-1990s, and the results are mixed. Geographic markers of the successes and failures of this integration abound: the stream of legal and illegal migrants into the United States—often people who have lost their livelihoods to NAFTA-supported enterprises; the towering fences along the border with the United States (see Figure 3.30A); the interconnecting highway systems crowded with trucks carrying products between the three countries; and the ever-changing maquiladora phenomenon that continues to attract recession-plagued U.S. manufacturers, which meanwhile is shrinking due to the recession.  71. DRUG MONEY WORSENS CORRUPTION IN MEXICO

71. DRUG MONEY WORSENS CORRUPTION IN MEXICO

Formal and Informal Economies

Mexico’s formal economy has modernized rapidly in recent decades. Its main components are mechanized, export-oriented agriculture, a vastly expanded manufacturing sector, petroleum extraction and refining, tourism, a service and information sector, and the remittances of millions of migrants working abroad. Mexico’s large and varied informal economy employs an estimated 16 million people at least part time—about half of the total working population of 33 million. Informal economy workers contribute at least 13 percent of the GDP through such activities as subsistence agriculture, fine craft making, and many types of services, ranging from street vending and tutoring to trash recycling. The informal economy also includes any remittances smuggled home, a flourishing black market, and the crime sector.

Geographic Distribution of Economic Sectors

Mexico’s economic sectors have a distinct geographic distribution pattern. The agricultural (or primary) sector employs about 14 percent of Mexico’s population. However, agriculture produces only 4 percent of Mexico’s GDP, and only 12 percent of Mexico’s land is good for agriculture, much of that comprised of hillsides. In the northwest and northeast, large corporate farms, often run by American companies, have replaced the old, inefficient haciendas and ranches that formerly hired scores of workers at very low wages. The corporate farms employ only a few laborers and technicians. With the aid of government marketing, research, mechanization, and irrigation programs, their products—high-quality meat and produce such as asparagus, peppers, winter vegetables, and raspberries, as well as corn and sorghum—go primarily to the North American market. In the tropical coastal lowlands farther south, subsistence cultivation on small plots is much more common, but here, too, tropical fruits and products such as jute, sisal, and tequila are produced for export as well as for internal consumption. In Mexico’s convoluted mountains, many small family farms produce a wide variety of crops, including coffee, corn, tomatoes, sesame seeds, hot peppers, and flowers.

The service (or tertiary) sector is the largest, employing 63 percent of the population and producing 62 percent of the GDP. Service jobs are most varied and noticeable in the big cities. Work in services includes restaurants, hotels, tourism facilities of all sorts, financial and educational institutions, consulting firms, and museums. The service sector is dominated by small operations that cater to everyday needs: shoe repair, Internet cafés, cleaning services, beauty parlors—many in the informal economy.

The Maquiladora Phenomenon

The industrial (or secondary) sector, which includes Mexico’s profitable petroleum refining industry that is located along the Gulf coastal plain, employs about 23 percent of Mexico’s registered workforce and accounts for 34 percent of the GDP. Industries are found in many geography niches, rural and urban, but a particular kind is concentrated along the U.S. border; these are the maquiladoras, in cities that include Tijuana, Mexicali, Ciudad Juárez, and Reynosa, that hire people to assemble manufactured goods, such as clothing or electronic devices, usually from duty-free imported parts. By 2009, a combination of the global recession, cheaper industrial venues in Asia, and violence perpetrated by Mexican drug cartels resulted in a contraction of the maquiladora phenomenon. At the beginning of 2010, however, Mexico was recovering from the global recession, and businesspeople in the Maquiladora Association in Ciudad Juárez reported new plants opening and employment rising.

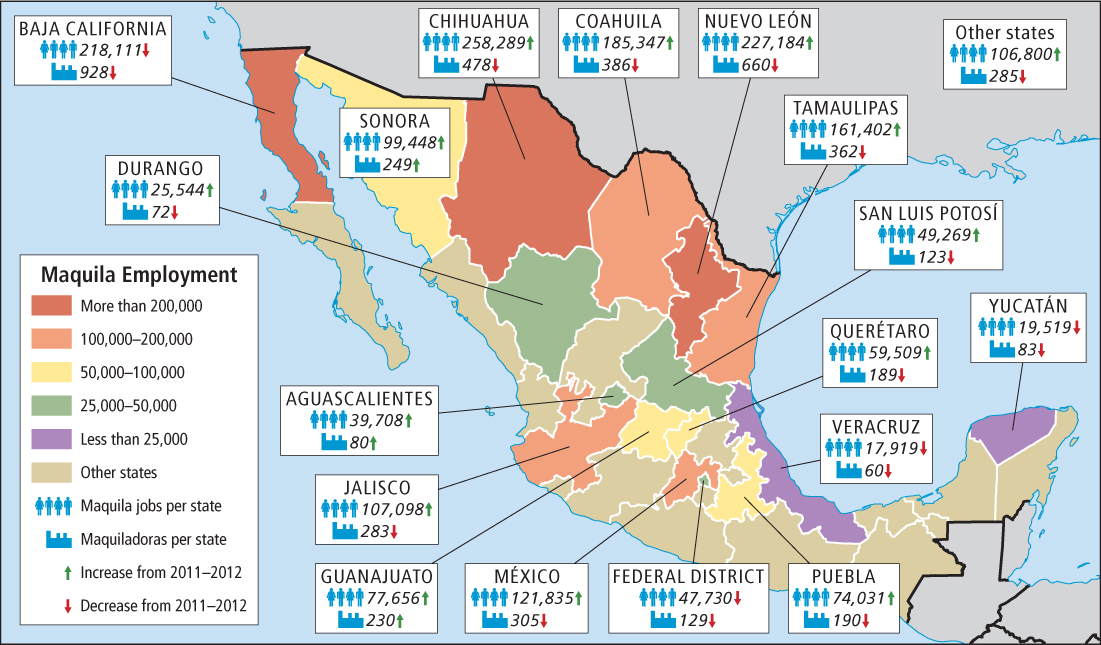

Location of Maquiladoras

The Mexican side of the border is a desirable location for the maquiladoras because it provides an inexpensive labor pool within easy reach of the U.S. market (Figure 3.31). In 2011, Mexican factory workers earned an average of about U.S.$9 per day ($1.10 per hour). Compared to the United States, Mexico has far fewer regulations covering worker safety, fringe benefits, and environmental protection, and it charges much lower taxes on industries. These conditions attracted a considerable number of maquiladoras even before NAFTA took effect in 1994; after NAFTA took effect, the number of maquiladoras increased dramatically.

Gender in Maquiladoras

For many years women have been the employees of choice in maquiladoras because they are more compliant than men, they work on short-term contracts for less pay, and, if fired, they leave quietly. Thousands of young women previously sheltered by close-knit families now live in precarious, crowded circumstances where they are preyed upon by employers and by violent mates, gangs, and drug cartels. For example, the murders of hundreds of young women in Juárez remain unsolved. Nonetheless, young women continue to migrate to the maquiladoras because the remittances they send home are crucial to their families’ welfare, and these financial contributions give female workers a high status in the family that earlier generations of women did not enjoy. Men, recently displaced from agriculture and local factory work, are increasingly employed in maquiladoras, filling traditionally female jobs such as sewing or assembling electronic devices. They are viewed as more competent than female workers. Recent studies have shown that the majority of women employees do not use maquiladora work as a precursor to migration to the United States, as often has been claimed; if these migrants fail to find maquiladora work, they tend to return to their home villages.

The Downside of Maquiladoras for Mexico

Although many Mexicans are pleased to have the maquiladoras and the jobs they bring, the country is increasingly facing negative side effects. The border area has developed serious groundwater and air pollution problems because of the high concentration of poorly regulated factories and the hundreds of thousands of people living in unplanned worker shantytowns. Social problems are also developing among those crowded into unsanitary living conditions, and family violence is high. The schools in the border cities are inadequate for the increasing number of children. In Ciudad Juárez in 2001, for example, there were just 10 day-care centers serving 180,000 women workers. An additional problem is that governmental authority is fragmented along the long border zone where there are 14 paired U.S.–Mexican cities. The multiplicity of governments makes it difficult to address common problems. To address this issue of overlapping governments, the U.S.–Mexico Border XXI Project, under the auspices of both the U.S. and Mexican governments, has organized joint task forces that focus on infant immunization, drinking water procurement, water and air pollution mitigation, hazardous waste prevention and cleanup, environmental studies, and border security.

Migration from the Mexican Perspective

The movement of Mexicans to the United States to find work is as controversial in Mexico as it is in the United States because Mexico is losing many citizens (and parents) during their most productive years. Parents leave children to be raised by grandparents or other kin. And there is worry over the safety of family members while crossing the border and when on the job.

Unlike the many Europeans who cut ties with their families and native land when they migrated to North America, Mexicans often undertake their migrations with the express purpose of helping out their families and home communities. In recent years, Mexican workers in the United States remitted an estimated $20 billion annually to their home communities (see the discussion). Most Mexican households receiving remittances are located in relatively better-off states such as Michoacán and Zacatecas, because residents of the poorest states find it difficult to finance a migration to the United States.

Does migration have to be the main route to advancement for Mexico’s youth? Maybe not. Mexicans with more than a high school education are much less likely to migrate than those with just 9 to 12 years of schooling. Since about 37 percent of the Mexican population already uses the Internet (see Figure 3.23), government programs are trying to expand use of the Internet as a means of getting training and higher education to young adults in order to give them a potentially brighter future at home than they are likely to find as migrants in North America. Nonetheless, migration is still an important way in which Mexican families improve their well-being.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Mexico has a fragile democracy that is threatened by the violence and civil disorder of the traffic in illegal drugs by powerful drug cartels.

Mexico has a fragile democracy that is threatened by the violence and civil disorder of the traffic in illegal drugs by powerful drug cartels. Mexico’s diversifying economy is in part based on the maquiladoras that have resulted from NAFTA, as well as petroleum revenues, remittances, and tourism.

Mexico’s diversifying economy is in part based on the maquiladoras that have resulted from NAFTA, as well as petroleum revenues, remittances, and tourism. The country must deal with increasing problems posed by emigration to the United States.

The country must deal with increasing problems posed by emigration to the United States.