Environmental Issues

Geographic Insight 1

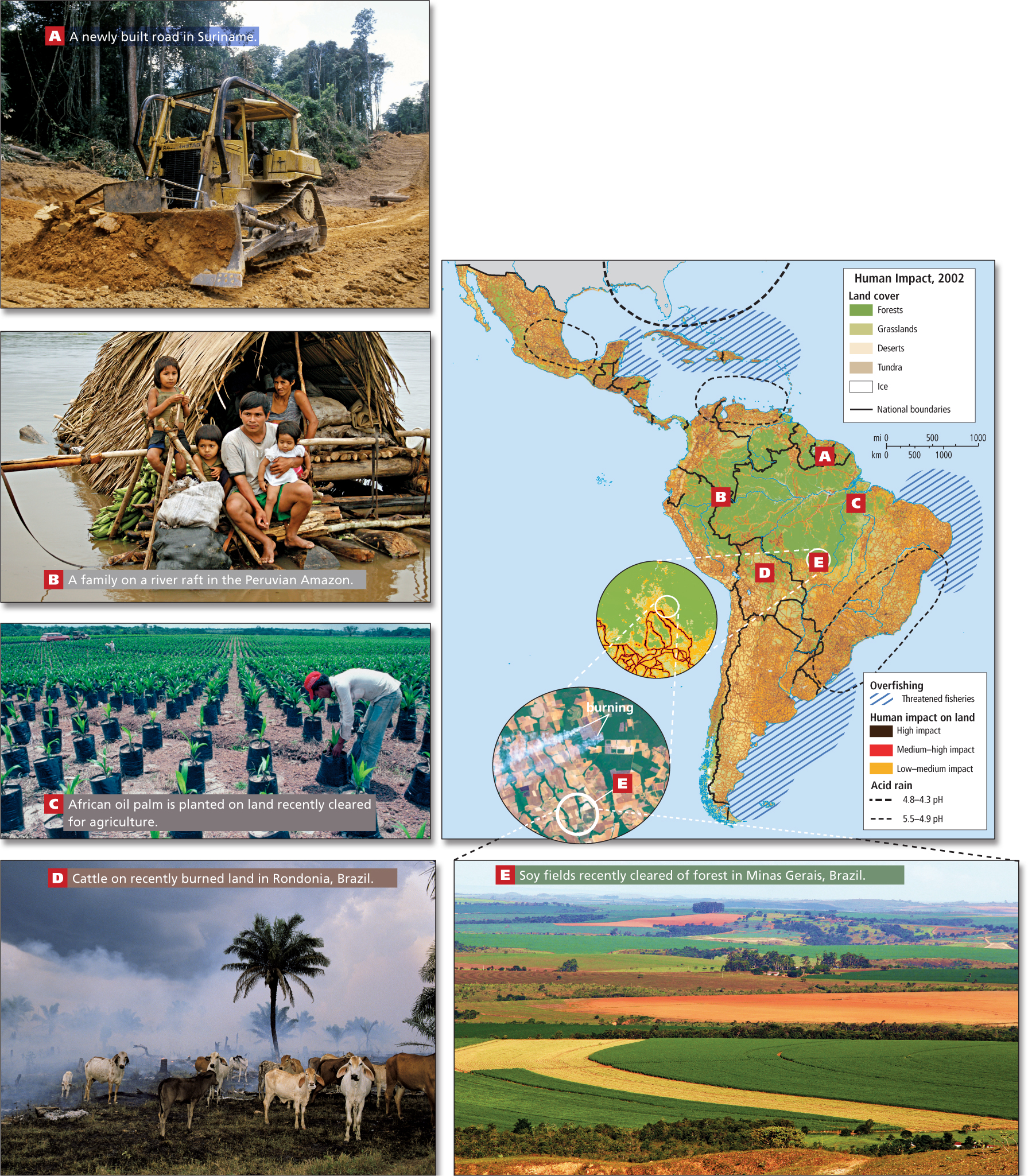

Climate Change and Deforestation: Deforestation in this region contributes to climate change by removing trees, which as living plants naturally absorb carbon dioxide. As the cut vegetation decays, large amounts of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere. Sustainable alternatives to deforestation are being tried.

Environments in Middle and South America have long inspired concern about the use and misuse of the Earth’s resources. Millennia before Europeans arrived in this region, human settlements in the Americas had major environmental impacts. However, today’s impacts are particularly severe because both population density and per capita consumption have increased so dramatically. Moreover, local environments now supply global demands.

Tropical Forests, Climate Change, and Globalization

A period of rapid deforestation that has had global repercussions began in the 1970s in Brazil with the construction of the Trans-Amazon Highway. Migrant farmers followed the new road into the rain forest. They began clearing terrain to grow crops, prompting a few observers to warn of an impending crisis of deforestation. Initially, concern focused on the loss of plant and animal species, as the rain forests of the Amazon Basin are some of the most biodiverse on the planet. (Please note that the Amazon includes parts of Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil; see Figure 3.1.) However, climate change now dominates concerns about deforestation in the Amazon and the rest of this region. As explained in Chapter 1 (see Drivers of Global Climate Change), forests release oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide (CO2), the greenhouse gas most responsible for global warming. The loss of large forests, such as those in the Amazon Basin, contributes to global warming by releasing CO2 once locked in the woody bodies of trees. This CO2 release happens as trees are burned to make way for crops and roads. When there are fewer trees, less CO2 can be absorbed from the atmosphere. Together, all of the Earth’s tropical rain forests absorb about 18 percent of the CO2 added to the atmosphere yearly by human activity. Because 50 percent of the Earth’s remaining tropical rain forests are in South America, keeping these forests intact is crucial to controlling climate change.

Middle and South American rain forests are being diminished by multiple human impacts (Figure 3.8). One of the biggest impacts is caused by the clearing of land to raise cattle and grow crops such as soybeans (for animal feed), sugarcane (for ethanol), and African oil palm (for cooking oil) (see Figures 3.8C and 3.8E). Brazil now ranks as the world’s fourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after the United States, China, and Indonesia. In the Amazon, Middle America, and elsewhere in the region, forests are cleared to create pastures for beef cattle, many of which are destined for the U.S. fast-food industry. If deforestation continues in Middle America at the present rates, the natural forest cover will be entirely gone in 20 years.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about human impacts on the biosphere in Middle and South America, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What environmental impact is clearly visible in this photo?

What environmental impact is clearly visible in this photo?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

What land use likely preceded cattle grazing on the land shown in this photograph?

What land use likely preceded cattle grazing on the land shown in this photograph?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Where are the soybeans grown on this land likely to end up?

Where are the soybeans grown on this land likely to end up?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Hardwood logging and the extraction of underlying minerals, including oil, gas, and precious stones, are also contributing to deforestation. Investment capital comes from Asian multinational companies that have turned to the Amazon forests after having logged up to 50 percent of the tropical forests in Southeast Asia. Moreover, the construction of access roads to support these activities continues to accelerate deforestation by opening new forest areas to migrants. The governments of Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil encourage impoverished urban people to occupy cheap land along the newly built roads (see Figure 3.8A) and encourage deforestation by supplying chainsaws to the settlers. However, the settlers have a difficult time learning to cultivate the poor soils of the Amazon. After a few years of farming, they often abandon the land, now eroded and depleted of nutrients, and move on to new plots. Ranchers may then buy the worn-out land from these failed small farmers to use as cattle pastures (see Figure 3.8D).

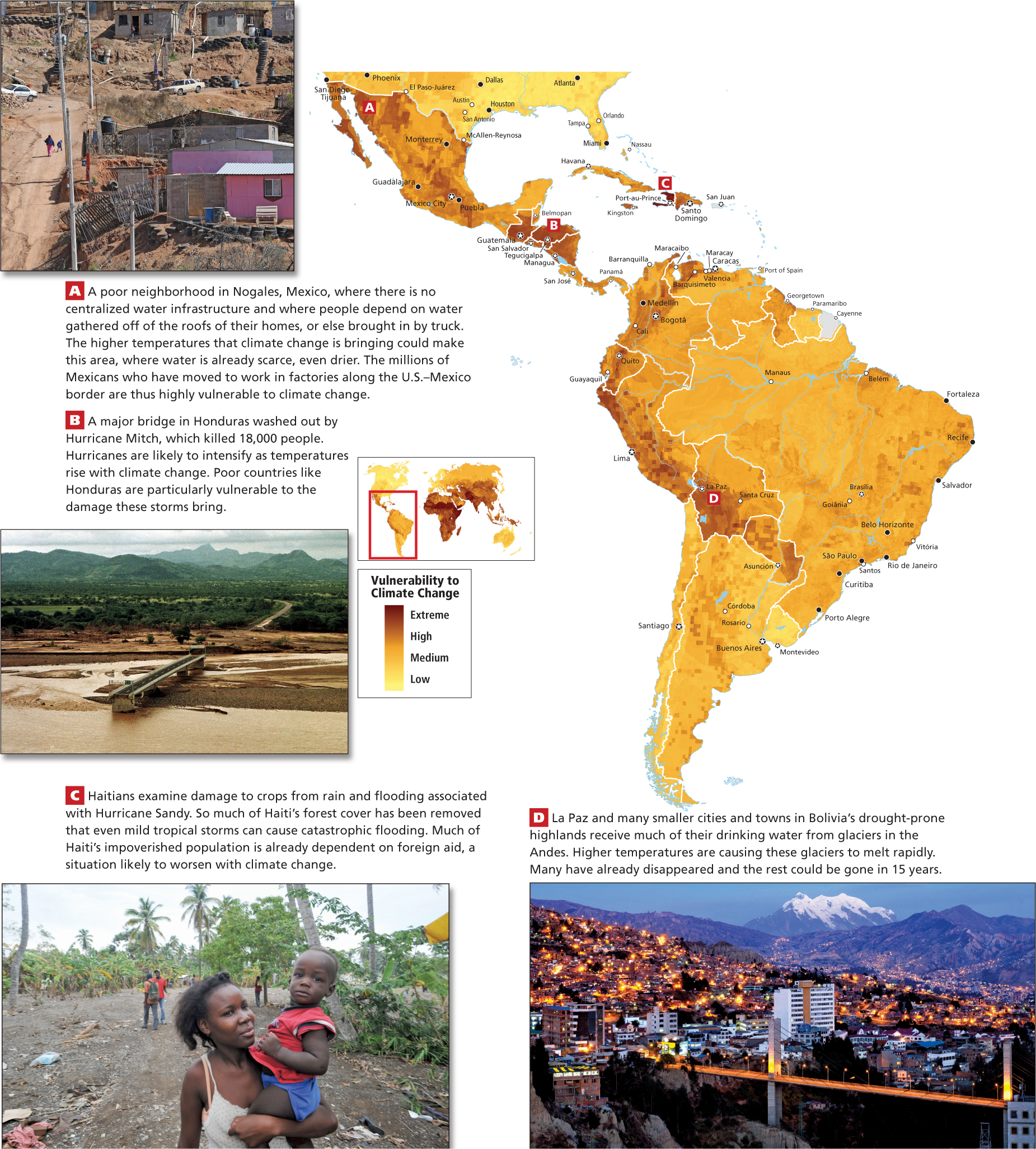

While Middle and South America are significantly contributing to global warming by adding CO2 to the Earth’s atmosphere, many people in this region are particularly vulnerable to the increasing threats of climate change. Figure 3.10 illustrates several such cases: shortages of clean water brought on by intensifying droughts and by glacial melting; vulnerability to rising sea levels; and the effects of increasingly violent storms.

Major international efforts are under way to combat climate change by preserving the world’s remaining forests, especially the crucial tropical rain forests found in this region. Integrating sustainable yet profitable agroforestry (tree cropping) into existing forests has been found to be among the cheapest ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. When well-funded and carefully executed, such efforts have the potential to save forests throughout the region. However, implementing complex agroforestry programs, which will require cooperation between diverse groups, will be an enormous challenge (see Climate Change and Deforestation in Chapter 10).

Environmental Protection and Economic Development

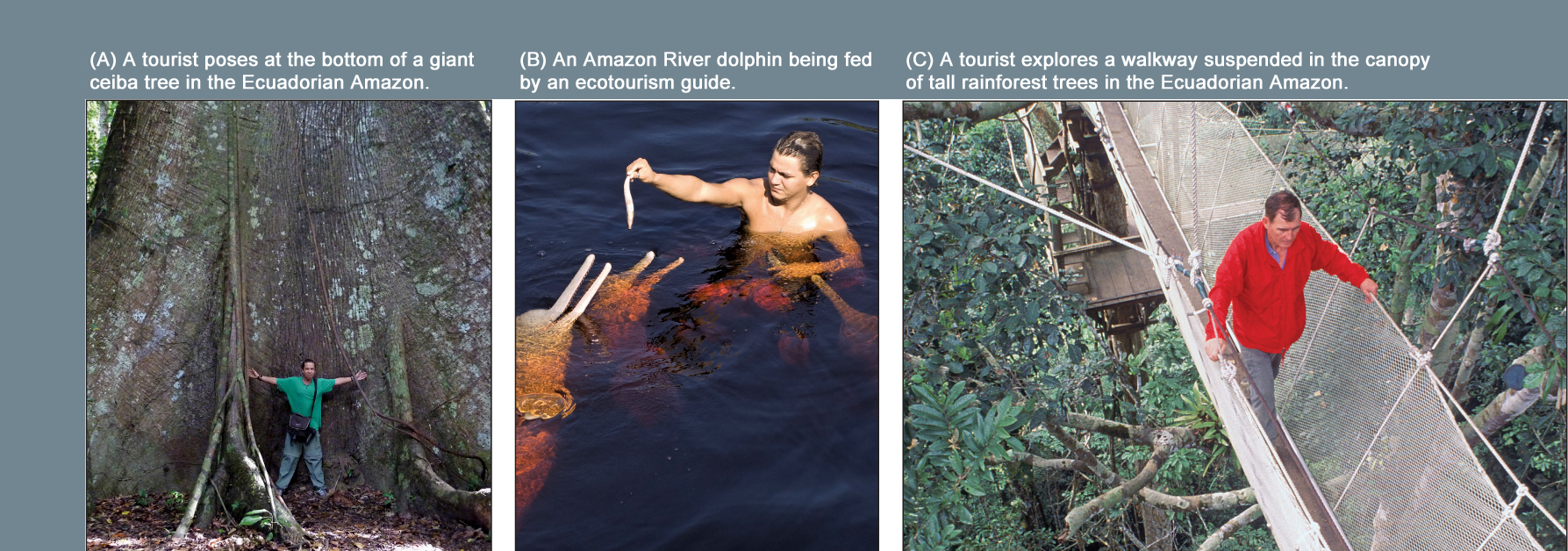

In the past, governments in the region argued that economic development was so desperately needed that environmental regulations were an unaffordable luxury. Now, there are increasing attempts to embrace both economic development and environmental protection. One example of this new approach is ecotourism.

Ecotourism

ecotourism nature-oriented vacations, often taken in endangered and remote landscapes, usually by travelers from affluent nations

Ecotourism has its downsides, however. Mismanaged, it can be similar to other kinds of tourism that damage the environment and return little to the surrounding community. While the profits of ecotourism can potentially be used to benefit local communities and environments, the profit margins may be small.

VIGNETTE

Puerto Misahualli, a small river boomtown in the Ecuadorian Amazon, is currently enjoying significant economic growth. Its prosperity is due to the many European, North American, and other foreign travelers who come for experiences that will bring them closer to the now-legendary rain forests of the Amazon.

The array of ecotourism offerings can be perplexing. One indigenous man offers to be a visitor’s guide for as long as desired, traveling by boat and on foot, camping out in “untouched forest teeming with wildlife.” His guarantee that they will eat monkeys and birds does not seem to promise the nonintrusive, sustainable experience the visitor might be seeking. At a well-known “eco-lodge,” visitors are offered a plush room with a river view, a chlorinated swimming pool, and a fancy restaurant serving “international cuisine.” All of this is on a private 740-acre nature reserve separated from the surrounding community by a wall topped with broken glass. It seems more like a fortified resort than an eco-lodge.

By contrast, the solar-powered Yachana Lodge has simple rooms and local cuisine. Its knowledgeable resident naturalist is a veteran of many campaigns to preserve Ecuador’s wilderness. Profits from the lodge fund a local clinic and various programs that teach sustainable agricultural methods that protect the fragile Amazon soils while increasing farmers’ earnings from surplus produce. The nonprofit group running the Yachana Lodge—the Foundation for Integrated Education and Development—earns just barely enough to sustain the clinic and agricultural programs. [Source: Alex Pulsipher’s field notes in Ecuador.]

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Alternatives to Deforestation

Ecotourism is now the most rapidly growing segment of the global tourism and travel industry, which by some measures is the world’s largest industry, with $3.5 trillion spent annually. Many Middle and South American nations also have spectacular national parks that can provide a basis for ecotourism. As an alternative to deforestation, development based on ecotourism has the potential to preserve this region’s biodiversity, reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, and provide less affluent and indigenous people with a chance to use their skills to teach tourists.

The Water Crisis

Geographic Insight 2

Water: Despite the region’s abundant water resources, parts of the region are experiencing a water crisis related to unplanned urbanization; marketization; corruption; inadequate water infrastructure; and the use of water to irrigate commercial agriculture.

Although Middle and South America receive more rainfall than any other world region and have three of the world’s six largest rivers (in volume), parts of the region are experiencing water crises (Figure 3.10). Most of the factors causing the water crises are induced by humans, who in turn are now exposed to a variety of water-related stresses. For example, the air pollution that hangs over so many cities in Middle and South America contributes to global warming, which in turn accelerates glacial melting in the Andes. The glaciers feed rivers that are the main source of water for millions (see Figure 3.10D). Should the glaciers actually disappear, the rivers will at best run only seasonally, devastating communities and industries that depend on them.

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about vulnerability to climate change in Middle and South America, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

What clues can be seen in this photo that the neighborhood lacks a centralized water distribution system?

What clues can be seen in this photo that the neighborhood lacks a centralized water distribution system?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

From which direction are hurricanes most likely to hit Honduras?

From which direction are hurricanes most likely to hit Honduras?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

In addition to Haiti's exposure to tropical storms and hurricanes, what else contributes to its vulnerability to climate change?

In addition to Haiti's exposure to tropical storms and hurricanes, what else contributes to its vulnerability to climate change?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

Why is glacial melting of particular concern to cities in Bolivia?

Why is glacial melting of particular concern to cities in Bolivia?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Lax environmental policies allow industries to pollute both air and water with few restraints. Waterways along the Mexican border with the United States are polluted by numerous factories set up to take advantage of NAFTA-related trade with the United States and Canada (see discussion of maquiladoras). Only a small percentage of the often highly toxic water discharges are treated and disposed of properly. And in Mexico City, it is estimated that as much as 90 percent of urban wastewater goes untreated.

Rapid urbanization, combined with corruption, inadequate investment, and misguided policies, has left many people without access to clean water or sanitation. In some of the largest cities, the water infrastructure is so inadequate that as much as 50 percent of the fresh water is lost because of leaky pipes (see Figure 3.10A). Often as much as 80 percent of the population has no access to decent sanitation; toilets are sometimes entirely lacking, leaving people to relieve themselves on the city streets. This poses a major health hazard. Uncontrolled dumping of wastewater so pollutes local water resources that cities must bring in drinking water from distant areas.

Behind these immediate problems lie systemic policy failures and inadequate planning, such as that in Cochabamba, Bolivia (discussed in Chapter 1). There, efforts to improve the city’s inadequate water supply system focused on “marketizing” the water system. The water supply, long thought of as a public resource, was sold to a group of foreign corporations led by Bechtel of San Francisco, California. The hope was that Bechtel, in return for profits, would make investments in infrastructure that Cochabamba’s notoriously corrupt water utility would not make. Unfortunately, Bechtel, unfamiliar with the actual living conditions of the majority of citizens, immediately increased water prices to levels that few urban residents could afford, while doing little to improve water supply or delivery systems. At one point Bechtel even charged urban residents for water taken from their own wells and rainwater harvested off their roofs! Popular protests forced Bechtel to abandon Cochabamba’s water utility, which remains plagued by corruption and an inadequate infrastructure.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 1Climate Change and Deforestation The rapid loss of forests in this region is a major contributor to climate change. Trees absorb huge amounts of carbon dioxide in their bodies; the carbon dioxide is released when forests are cleared through burning.

Geographic Insight 1Climate Change and Deforestation The rapid loss of forests in this region is a major contributor to climate change. Trees absorb huge amounts of carbon dioxide in their bodies; the carbon dioxide is released when forests are cleared through burning. Geographic Insight 2Water Despite considerable water resources, parts of this region are experiencing a water crisis related to rapid urbanization, corruption, inadequate investment in infrastructure, misguided policies, and the use of water to irrigate commercial agriculture. Many people have inadequate access to sanitation, and the dumping of waste in rivers is widespread.

Geographic Insight 2Water Despite considerable water resources, parts of this region are experiencing a water crisis related to rapid urbanization, corruption, inadequate investment in infrastructure, misguided policies, and the use of water to irrigate commercial agriculture. Many people have inadequate access to sanitation, and the dumping of waste in rivers is widespread.